Identity & Culture

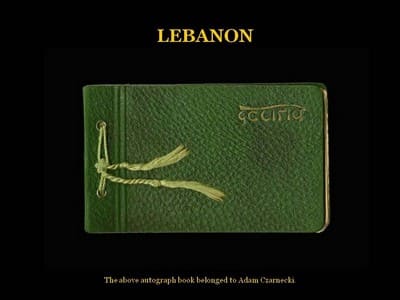

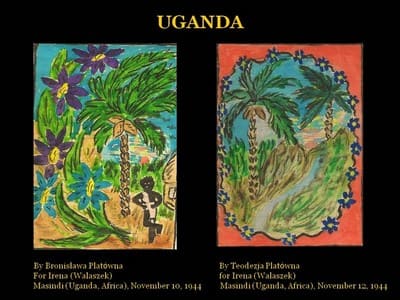

Autograph books and diaries of Polish children in exile – 1940-1950

INFORMATION

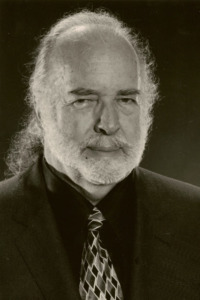

CURATOR OF THE EXHIBITION

WESLEY ADAMCZYK

WESLEY ADAMCZYK

Wesley Adamczyk is the author of „When God Looked the Other Way”, published by University of Chicago Press, major contributor to “Children of the Katyn Massacre”, published by McFarland and Co., and a contributor to “Polskie dzieci na tulaczych szlakach 1939-1950”, published in 2008 by IPN in Poland. He is also an activist who has devoted his retirement years to the dissemination of information about the deportation of Polish people to Siberia and the Katyn massacre.

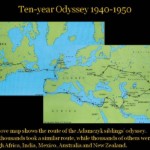

Born in Warsaw in 1933, Mr. Adamczyk was deported to Siberia in 1940 and escaped in 1942. His mother died soon after they reached freedom in Persia. Only later, Mr. Adamczyk learned that his father had been murdered in the Katyn massacre. Mr. Adamczyk came to the United States in 1949, at the age of 16, after his ten-year odyssey that took him across four continents and 12 countries. He is a graduate of DePaul University where he obtained a degree in chemistry and philosophy.

His exhibition examines the correlation between identity and culture as shown through the drawings of the exiled children; and through the inscriptions of the children that will reveal what was in their heart and soul during the exile.

FROM THE CURATOR

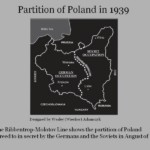

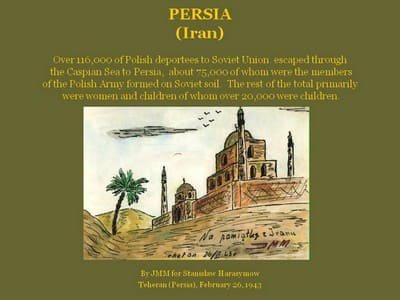

This exhibition is based on the drawings and inscriptions in the autograph books and diaries of Polish children who were deported from Poland to the Soviet Union in 1940-41 by the Soviets early in World War II. I was one of those children.

After two years of enslavement in inhuman conditions, thousands of us managed to escape in 1942 to freedom in Persia. Most of us were sick and famished, while many others were orphaned. Because of the deportation and exile, I have spent nearly ten years with these children in foreign lands, whether in the mud-huts of Siberia, the camel stables of Persia, or the Quonset huts of England. In spite of the fact that we were homeless and without a country, we brought with us our Polish culture, traditions, and the values our parents taught us. It was for this reason that the ancient city of Isfahan, the old capital of the mighty Persian Empire where many of us settled, was often referred to as “the city of Polish children”.

Our identity with our culture, heritage, and values was not something we thought about, it was a part of our character, as natural as breathing.

Today, seven decades later, when I read the inscriptions thousands of exiled children wrote in their autograph books and diaries decades ago, I became convinced that it was our identity with our culture and heritage that helped us to survive the long exile.

Speaking for a lonely exiled orphan of yester-years, this is what I wrote in my book, When God Looked the Other Way:

“I carried my home in my heart and found a way to escape there for comfort – in times of doubt, for wisdom; in times of fear, for courage; in times of loneliness, for love.”

Wesley (Wiesław) Adamczyk

Chicago, 17 September 2009

BUILDING AND STRENGTHENING THE BORDER

For 123 years, the Polish state was torn apart by the partitioning powers, Germany, Russia and Austria-Hungary. The borders of the partitioning powers were marked with wooden, stone or cast iron border posts. The coats of arms of countries were placed on these poles. Each character had its consecutive number.

Regaining independence by Poland started a difficult period of consolidating the state, which lasted for many years. Its boundaries were shaped by the struggle. The delineation and marking of borders was dealt with by international commissions. Initially, piles, panicles were used, dikes, mounds or pyramids made of stones were usually marked with the first letters of the names of the neighboring countries and subsequent numbers. Then they were exchanged for appropriate border marks, the unified pattern of which for a given border was specified in the relevant treaty documents.

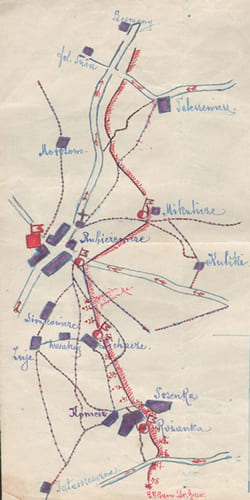

The Polish-Soviet state border was established in March 1921, after the Polish-Bolshevik war, at a conference in Riga. In the following year, on November 23, 1922, in Rivne, Volhynia, the Polish-Soviet team of the Mixed Border Commission signed the final act of handing over to the border, administrative and customs authorities, Poland and the Soviet Republic, the delimited and strewn state border. It differed slightly from the treaty line not only in the fact that it had already been carried out in the field, but also in the fact that it also included Polish settlements, which the Polish Delegation of the Mixed Border Committee in the East managed to recover for Poland through an exchange of equivalents.

It started from the Polish-Soviet-Latvian tripoint situated on the Dvina River and ran west of Minsk, along an arc that stretched between the Berezina and Pripyat Rivers. Then along the Słucz River, and then it ran through the marshes of Polesie between Mikaszewicze (in Poland) and Zwiahel (in the USSR). Here, the border turned south-west through Ostroh to the Zbrucz River and further to its estuary to the Dniester, where near the village of Okopy Holy Trinity there was a tripoint with Romania.

The 1,412 km-long border was marked with 2,290 consecutively numbered border marks. It was assumed that the border marks would be wooden poles 2.5-3.5 m high. The Polish ones were painted with diagonal white and red stripes, the Soviet ones with horizontal red and green stripes. Cast-iron plaques with an eagle according to the pattern from 1919 and the inscription Rzeczpospolita Polska were attached to Polish poles. On the section of the border running along the Zbrucz River, the existing Austrian cast-iron border posts were used, on which plates with the national coat of arms were simply listed. It was the former border between Russia and the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the so-called The Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria. It is a little known fact that Austrian cast-iron border posts were made in a foundry in Cieszyn. On the other hand, Polish plaques with the eagle in the iron foundry in Poręba and in the Ludwik Minchejmer Button and Metal Products Factory in Warsaw. The Warsaw plaques are made of zamak – an alloy of zinc and aluminum.

After the Treaty of Riga, the Commonwealth occupied the territory of 388,634 km2, which placed it in the sixth place in Europe in terms of area, and the total length of the borders was 5,529 km, of which the maritime border was 140 km (border of territorial waters 104 km), and land borders 5389 km, including:

– 1912 km with Germany (607 km with East Prussia),

– with Czechoslovakia 984 km,

– with Romania 347 km,

– 1412 km from the USSR,

– with Lithuania 507 km,

– 106 km with Latvia,

– 121 km from the Free City of Gdańsk.

The establishment of the KOP was therefore associated with an enormous financial and organizational effort by the young Polish State. The eastern border was a particularly difficult border in terms of terrain – only in very short sections it ran along natural partitions, which were small sections of the rivers: Zbrucz in the Tarnopol voivodship, Słucz and Morocz in the voivodship. Polesie and partly the Daugava River in the Vilnius Land. Much longer, the remaining fragments of the border were not natural obstacles: very difficult to maintain tightness, running in a densely forested area, cut by ravines, ravines and valleys, and in Polesie by swamps and marshes, they favored the formation of the so-called “Green border”, not easy to protect against smuggling and diversion …

TRAINING

The Border Protection Corps was an elite formation. He was not sent to “civilian” conscripts, but only soldiers from Polish Army units after basic training. KOP officers also studied various types of weapons in officer schools. The corps, however, as it developed, trained its non-commissioned officers itself – in 1926 the Schools of NCOs were established: Infantry in Ostrog and Cavalry in Niewirków and the School of Non-commissioned Infantry in Mizocz, Baranowicze, Wilejka, Skala n / Zbrucz, Ludwików and Oklenniki. Pioneer Training Centers were also opened in Hoszcza, Kleck, Budsław, Mosty Wielkie, Dawidgródek and Vilnius. The whole picture of KOP education was completed by the Registration Dog Training School in Kleck. Soldiers directed to the eastern border were trained in general military terms, but did not know the specificity of the border service. For this reason, various types of courses were organized.

The education was conducted by educational officers and non-commissioned officers. On the other hand, border training was based on consolidating military knowledge adapted to the realities of the borderland, improving shooting and tactical skills, as well as combat operations. Most of the time was devoted to military, not border issues. Non-commissioned officers were trained in the Schools of Vocational NCOs: Infantry and Cavalry, established in 1926, as well as the Infantry NCO Schools (including in Baranowicze, Wilejka) and the Registration Dog Training School in Kleck.

In 1928, the KOP education system was reorganized and the School Battalion in Osowiec was created on the basis of the non-commissioned officers’ schools, renamed in 1930 into the Central NCO School of the KOP. Much attention was paid to engineer training, therefore Pioneer Training Centers were established, whose task was to prepare engineer teams. Sports sections operated in KOP sub-units, e.g. fencing, equestrian, swimming, shooting, cycling, skiing, basketball and football. Every year, relay races were organized. Educational work supplemented the shaping of the desired attitude of the KOP soldiers. It was concentrated in common rooms, where talks were held, theaters and music bands performed, films were shown, radio broadcasts were broadcast, newspapers and books were read. In elementary schools for illiterate students, apart from teaching reading and writing, efforts were made to pass on knowledge in mathematics, history and geography. Courses for professional non-commissioned officers lasted 6 months. It was customary to end solemnly on the national holiday of May 3 and the national holiday of November 11, which was also the holiday of the entire Corps.

In 1928, during the reorganization of the organizational structure, the reorganization of NCO schools was also started. August 28, 1928 The KOP School Battalion was formed on the basis of the NCOs of the KOP brigades and the KOP Vocational NCO School in Ostrog. The walls of the former Tsarist Fortress in Osowiec were designated as its stopping place. It was to train both professional and non-commissioned officers of the Corps. The first battalion commander was appointed Maj. Marian Porwit. The first courses were held from August 27 to December 20, 1928 for non-commissioned officers and from November 15, 1928 to May 3, 1929 for professional non-commissioned officers. They were attended by 98 and 58 soldiers of the KOP, respectively, on February 28, 1930, the commander of the KOP, Brig. Stanisław Tessaro renamed the KOP School Battalion to the Central School of NCOs of the Border Protection Corps. A month earlier, Maj. Porwit replaced Maj. Bronisław Laliczyński. As a result of the reorganization, two existing shooting companies were liquidated and a student training company (specialists) and a second machine gun training company were formed. After the reorganization, the school consisted of: the school headquarters, two school shooting companies, a school shooting company (specialists), two school machine gun companies, a school company of professional infantry non-commissioned officers. The executive order of the commander specified special requirements for the school staff. Therefore, he was to have high moral and physical qualifications, to have completed appropriate NCO schools with at least a good grade, and to have general education enabling them to act as educators. In accordance with the reorganization order, the instructors were additionally supplemented by professional non-commissioned officers, communication specialists and paramedics. Officers for the school were appointed by a personal order and were also subject to appropriate classification. Officers who worked in training and who had completed courses were preferred; weapons accompanying a given specialty, gas weapons and weapons in the field of sports preparation. An additional factor enabling the transfer was the bachelor status due to the lack of living quarters for families. At school, regardless of the specialization, approximately 55% of the time was spent on specialist training, 25% on general military training and 20% on general training

NETWORK OF BORDER WATCHES

The main issue for the effectiveness of the Corps was the accommodation of soldiers. Following the principles of the command strategy, the designed buildings were divided into three types:

– watchtowers (regular and representative) intended for half of the platoon, about 4 kilometers apart

– company reserve, each holding a platoon

– battalions, in which the complex housed: a company, a communications platoon, a machine gun company and the battalion commander’s team.

As KOP did not initially have an executive body to carry out the planned works, the patronage over the project was assumed by the Ministry of Public Works. The existing structure of the Construction of Clerical Houses in the Eastern Provinces (based in Brest-on-the-Bug) was used, led by Eng. Aleksander Próchnicki. The designated deadlines for the implementation of the investment were short, hence the announcement of the competition was abandoned and the plans by architect Tadeusz Nowakowski were used. The difficulties that occurred in the implementation of the project were related to a very poorly developed road and rail network, problems with obtaining seasoned wood, the lack of qualified construction workers and a small number of brick factories in the border regions. The first construction works began in mid-November 1924. In the years 1924-1927, only wooden buildings were built due to the need to introduce soldiers to the rooms as quickly as possible. From 1928, the conditions for carrying out the works became standardized, as the basic needs of the Corps (watchtowers) were satisfied and from that moment the use of refractory building materials (brick, concrete) was started. By 1931, 103 watchtowers, 39 company reserve units, 7 staff buildings, 8 battalion barracks, 5 battalion stables, 10 squadron barracks, 10 squadron stables and a whole series of farm and storage buildings with a total volume of 490,000 m3 were built.

ARMAMENT

The basic tactical unit in the Border Protection Corps was an infantry battalion and a cavalry squadron. The KOP battalion consisted of the commander’s team, a communications platoon, a machine gun platoon (from September 1931 – the company) and 3-5 rifle companies, each with 3 platoons, consisting of 4 teams. The KOP cavalry squadron had a commander’s team and 2 platoons, each with 4 sections (after 1932, a platoon was added, then the heavy machine gun team).

The infantry of the KOP was armed with repeating weapons – rifles (kb) and carbines (kbk), as well as light weapons (rkm, then also Ikm) and heavy machine guns (heavy machine guns). Later the K.O.P. also in high-speed weapons, i.e. mortars. The cavalry had repeating weapons – KBK and machine weapons (light, later and heavy), as well as sabers and lances. In the following years, the Corps was assigned artillery equipment – infantry cannons, anti-tank cannons and field cannons.

Weapons at the disposal of the newly created K.O.P. it came from the rearming of the infantry formations and from the reserve located in the central depots of the Polish Army. The obtained equipment, both quantitatively and qualitatively, fully satisfied the needs of the PEC as a formation dedicated only to border protection. However, as early as 1926 it was decided that some battalions of the KOP would be used to mobilize reserve infantry regiments in the war cover plan in the east. In this situation, it was necessary to standardize the repeating weapons possessed by the KOP with the military equipment.

In addition to the replacement of Austrian repeating weapons in the remaining KOP divisions, which lasted until 1928, and the allocation of other types of machine guns, it was decided to increase the number of heavy machine weapons in the divisions. This was dictated by new concepts of using, in the event of a war, some units of the KOP to deploy infantry divisions and the use of the remaining battalions for cover tasks in the first phase of military operations.

In addition to the replacement of Austrian repeating weapons in the remaining KOP divisions, which lasted until 1928, and the allocation of other types of machine guns, it was decided to increase the number of heavy machine weapons in the divisions. This was dictated by new concepts of using, in the event of a war, some units of the KOP to deploy infantry divisions and the use of the remaining battalions for cover tasks in the first phase of military operations.

The armament at the disposal of K.O.P. was subject to changes depending on the shaping of the concept of using this formation not only to ensure security in the border zone and to protect the border, but also in the event of war. As in the army, in the first years of the existence of the Corps, there was a variety of patterns of repeating weapons and machine guns. The reason for this was the prolonged process of unification of weapons in the armed forces of the Second Polish Republic. Only the beginning of the 1930s brought some improvement in this respect. In the branches of K.O.P. a uniform pattern of repeating weapons was introduced, with greater combat value, light machine guns were replaced with fully modern ones. This process ran with a certain delay in relation to the changes in the Polish Army. On the other hand, the replacement of heavy infantry weapons, i.e. heavy machine guns, mortars with newer designs, and the assignment of guns took place later and to a limited extent (e.g. heavy machine guns wz.1930 and mortars wz.1931), which largely reflected the difficult material situation of the armed forces of the Second Polish Republic. The KOP cavalry squadrons had basically the same weapons and in the same number as the line cavalry in the army. In terms of the number of weapons, the differences between the KOP infantry battalions and the battalions of active infantry regiments were small and due to their different organization.

K.O.P. artillery it had the equipment at the same technical and tactical level as the light artillery equipment of large units. However, the small number of cannons in relation to the needs and the total lack of howitzers meant that the Corps troops were inferior to equivalent military formations in this respect.

quoted from “Armaments of the Border Protection Corps 1924 – 1939” source: Museum of Polish Border Formations, www.muzeumsg.pl

EVERYDAY WORK

“Every ten days the commander and the deputy went to the company headquarters in Wiżajny for a briefing. They also obtained cigarettes, cleaning agents and newspapers for the army there. Three times a week as the deputy commander I conducted military training. These were two hours of exercise and drill. in the morning and two hours of talk in the afternoon. We had about 20 kilometers of the border to protect us. During the day, patrols were carried out individually, and at night, two soldiers each. The service of each soldier was four hours during the day and the same at night. The guards were in contact with the company command by telephone. Every now and then the company commander and his deputy came on horseback for inspection. Farmers from East Prussia and Lithuania owned land also on the Polish side. When they wanted to work on them, they had to report to the guards when and what kind of work will they do. Patrol duty was intensified then. “

It is obvious that not all the inhabitants of the border villages liked the KOP soldiers. The local population had to obey a strict law dictated that the state border was nearby. On the certificate confirming the place of residence of a farmer from the village of Grygaliszki, issued by the Suwałki Starosty in 1927, we read: “This certificate entitles you to stay outside of your seat only from sunrise to sunset. special permit outside his seat, that is, more than 100 steps from the place of domicile, and in any case you must not stay closer than 50 meters from the border. ” Therefore, we can easily imagine how troublesome was the life of the local residents. Older people recall that even to visit a neighbor in another town or go to a fair in Suwałki, it was necessary to obtain permission from the nearest watchtower. KOP institutions also decided whether a wedding or a dance party could be held in a given village. Of course, not all of them obtained such permits, because they were smugglers and were included in the “black list” of border services.

Smuggling at that time was organized on a large scale. Almost everything was illegally transported in both directions: salt, sugar, saccharin, pepper, tobacco, mushrooms, horsehair, alcohol and even cattle. KOP soldiers arranged ambushes on individual smugglers, and often on organized groups. They were led by the so-called “train drivers”, who assembled the group, collected the goods and organized the transfer across the border. Shots were often exchanged, which led to injuries or even death. There were also fights that the KOP had to fight with more bloody local smugglers. However, most of the locals respected the soldiers and understood their hard service. In numerous farms, the military could count on shelter from bad weather, rest, and even a modest snack.

In the interwar period, Wiżajny and its surroundings, apart from the Polish population, also included numerous Jewish and German circles. The KOP stationed here was a living symbol of the Polishness of these lands. Its soldiers actively participated in the local social and cultural life. They held patronage over schools. In 1934, they funded the inhabitants of Wiżajny a monument in honor of Józef Piłsudski, which was placed in the central part of the park.

K.O.P. AND SOCIETY

Already in the first year that elapsed since the KOP took up service, there was a marked decrease in sabotage and rapes, and a serious calming down of the border zone was recorded at that time. Two years later, the security of these areas was comparable to the areas in the interior of the country. And let the letters from the borderland population addressed to the authorities testify about how radically the security situation in the borderlands has changed, just after one year of service of the KOP. In one of them, the inhabitants of the Kremenets poviat wrote to the minister of internal affairs: “.. Today, thanks to the energy and heroism of the ranks of the 4th Battalion of the KOP, our homes are not on fire, the bandit, the Soviet servant, does not shed blood on us, and our weapons so far in our hands trembling with insomnia leased, it has already covered the dust of time in the lame. Behind the wall of breasts and bayonets of the 4th Battalion of the KOP, this borderland land blooms again, a life that is certain of a safe tomorrow has blossomed, and the inhabitant, consumed by daily toil, is quietly taking a rest … ”. This letter was signed by “Inhabitants of the Kremenets poviat” on two sheets of paper.

Another letter reads: “… as the mayor of this area, I feel it is a nice duty to inform J.W. Mr. Colonel, Commander of the 5th Brigade, that I was asked and authorized by the local population to express J.W. Our warm gratitude to Mr. Colonel that he sent us such a brave army, under whose protection we feel so safe here … ”. At the end of the letter, the mayor of the village of Chutory Merlińskie asked Mr. Mr. General and to J.W. Mr. Voivode, to whom, as our first representative of the Government, we would also like to express our gratitude for the grace that the Government showed us by sending us such a brave and generous army to defend us … “

Bożena Głosek in her work “Jak Polska Wierni” (in “Traces of Memory”, one-day program of the Association of Veterans of Polish Border Formations, Warsaw 2004) writes as follows:

The location of Wiżajny at the border with Lithuania and East Prussia was conducive to the development of smuggling, which posed a huge threat to the inhabitants of border villages. From March 1926, the border protection in this area was covered by the 6th KOP brigade, including the units of the 24th Battalion “Sejny”. The KOP “Wiżajny” company was located in Wiżajny itself. Apart from the basic task, which was securing the state border, the KOP units also performed important cultural and social functions.

The local population used libraries, community centers and military treatment. The soldiers actively participated in local life – they held patronage over the school. Marshal Józef Piłsudski, they were led by a group of scouts (now there is a scout team specializing in border guards), they helped in the daily activities of the population. They also participated in cultural and educational work. Founded here in 1926, “Teatr Żołnierski”, whose director in 1932. was Aug Betkier, staged various plays that were the only entertainment of the local population, which received them with great interest and joy. The income from the performances was allocated to a selected social goal, e.g. a school library.

Thanks to the efforts of the 24th KOP Battalion and the local society, in 1930 a monument to Marshal Józef Piłsudski – Chief of the Nation and already patron of the school in Wiżajny was erected in 1930. In ‘Żołnierz Polski’ no. 49 from 1930 we read:

“Garrison of Wiżajny. Unveiling of the monument to Marshal Piłsudski. In the town of Wiżajny, which is located north-west of Suwałki, in the place where the borders of three countries, Poland, Lithuania and Germany, are located – thanks to the efforts of 24 K.O.P battalion and the local society, Monument to Marshal Piłsudski.The fund for the construction of the monument was created from voluntary contributions from soldiers and citizens.This monument, although modest, is a decoration of the town and to posterity it will testify to the Polishness of this corner. , the fire brigade and the scout unit. The parade, accompanied by the sounds of the 24th battalion orchestra, marched along the streets of Wiżajny. of the brigade of Lieutenant Colonel Kalabiński, and then the service took place (…) Then they rushed to the ceremonial laying of the Marshal’s plaque in the local folk school, which was donated by Major Paszkiewicz. The ceremony of unveiling the monument made a strong impression on the local population, and especially on the soldiers of the Polish Army, who, while fulfilling their hard duties, made efforts to display a memento of the One whom the entire Polish army loves with their work. (Kapr. M. Nadolski) “