Part Three – Exile: Persia, India, England, Canada

Janina Sulkowska, 1934

Leon Gladun

Janka showing the effects of her bout of typhoid fever - Teheran, 1943.

Jan Sulkowski with his beloved orphans

Iranian Minister at Civilian Camp No.1, which housed Polish refugees. Both Janka and Jan Sulkowski (back row-left) taught here in 1942-1943, before going to India.

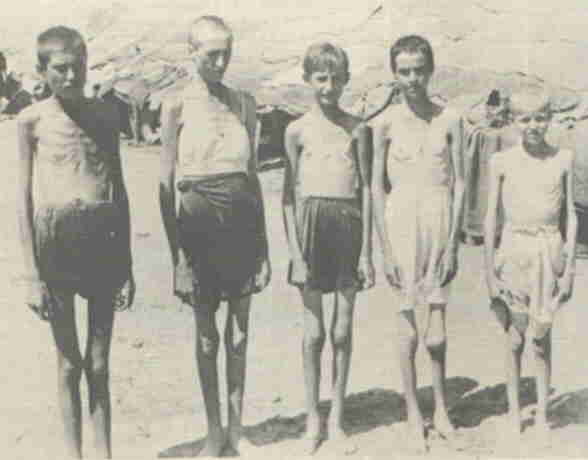

Polish Orphans in Teheran

Iranian Minister at Civilian Camp No.1, which housed Polish refugees. Both Janka and Jan Sulkowski (back row-left) taught here in 1942-1943, before going to India.

Persia – From Hell to Heaven!

Morning greeted us to a new world at Pahlevi. The water and sky were calm and blue–the sun no longer a blazing furnace. From our anchorage a mile offshore, we beheld sparkling beaches and a city of white tents and buildings. Excitement swept the ship as people cried and hugged. Small supply boats with fruit and vegetables (treasures to us!) sailed alongside our filthy ship. Then the Poles, some crawling or carried, were taken ashore. English soldiers in uniforms and white gloves, like waiters, appeared on the dazzling beach to offer us orange juice on silver trays. Smiling, they directed us toward the baths, fresh clothing and haircuts while doctors and nurses in clean smocks gathered up the sick. Polish refugees who’d arrived earlier frolicked on the beach. Everywhere there was food–and laughter. We’d gone from hell to heaven!

Along the beach stretched a city of tents, borrowed from the Iranians for the Polish army, side by side with palm huts for civilians. Eventually 200 British and 2,000 Persian tents would be utilized–and people still lived in the open. The refugee complex covered several miles on either side of the harbor, and housed Polish refugees who’d arrived in March and April. Ships full of Polish refugees had been arriving day and night, and the facilities ran 24-hours a day. The Polish and British authorities were well-organized and understanding; involved in our care was the Red Cross and other religious and charitable organizations. Persia, or Iran as it would be called, was divided into two spheres: the Anglo-American and the Soviet. The USSR led by Joseph Stalin, was no better than Nazi Germany…but now they were our “allies.” The British and certainly the Polish authorities, walked a fine line in this regard. This was now my home. Here the Persians would sell you eggs, fruit, souvenirs…and a few would steal your blankets.

Old Friends…and Typhoid Fever

Shortly after arrival, Leon Gladun, whom I had seen in Krasnoovodsk, came to visit me with wine and several pounds of halvah, that sweet delicacy. He’d arrived on August 26 aboard the Marx, with 575 soldiers and 507 civilians–one of the more spacious passages. Leon was overjoyed to leave “paradise” behind, as Poles referred to the USSR with bitter sarcasm. He had been here for less than a week, and in a week he was bound for Iraq and training with the British as part of the Polish Second Corps under General Anders. His intention was to gorge himself on food and swimming–and he was sticking to his regimen. Very quickly he was returning to the athletic figure that I knew from the sports fields of Krzemieniec High School. With Lilka Zurawska who’d been in the Polish army for half a year, the three of us went to a little beach café. I should have been happy and talkative, but I found myself glum and nauseous. Both the wine and the conversation seemed sour. My companions hoped it wasn’t the first signs of malaria…hundreds had already perished.

The next few days my fever increased–surely it was malaria. I was reduced to tossing and turning on an army bed, where one morning a voice informed me that my father had just arrived on the very last ship leaving the USSR. He had been evacuated with an orphanage and was now among the personnel of the Children’s Colony here. It was good news.

In spite of my feverish state, I decided that I would be better utilized among these children than in the army, which I disliked. After all I was a teacher and not a soldier. I insisted on going to see Jakub Hoffman who informed me that he had resigned his army position and was joining the Ministry of Labor and Welfare, to devote himself to educational and social work. He was taking Polish orphans to a new life in Africa. This confirmed my choice: the army accepted my resignation.

I immediately transferred to the civilian camp where I found a bed in the sand in a semi-hallucinatory state. I then went in search of my father at the Children’s Colony. In the barracks, as part of the personnel taking care of 400 orphaned and sick children, I found him alive–but very weak. He was reading a newspaper surrounded by his beloved children. We collapsed in each other’s arm, while an unspoken thought passed between us that we couldn’t allow ourselves to die…for the sake of Natalia and Wanda still in the USSR. He had arrived with his orphans from Bukhara aboard the Zhdanov, the final ship which left the USSR, overcrowded with 5130 people. For hundreds of thousands of remaining Poles it meant imprisonment in the Soviet Union.

I was taken to an area for victims of malaria, where I was put into bed with just a prayer for treatment. Medical care was stretched to the limit with not enough doctors or medicine. The Polish graveyard was winning the battle. But Marzenka Piatkwoska, my old Gulag companion, arrived at my bedside bearing quinine for my condition. She too had just made it across the Caspian Sea as a member of the Polish Army. Once more her uncompromising character urged me on. Marzenka stayed by my side as I descended into cramps, fever and hallucinations. Slowly I slipped into semi-consciousness and was taken to the main hospital. Here there were some 820 beds–and this was proving inadequate. And then it was discovered that I was suffering not from malaria, but from typhoid fever. I was disinfected and my head was shaved.

A soldier came to help me turn in my possessions at the hospital magazine. We felt something familiar in spite of our appearances: me sickly, and he in a uniform. It was Antoni Hermaszeswszki! The very one who helped me take my underground oath so long ago in Poland. He ordered me to get better so we could have a reunion. Death hovered near me…but the vigil of my father and friends, and wine, the only medicine available, pulled me through. I began my recovery by trying to walk from bed to bed. I set out on little expeditions along the seashore escorted by my father and friends. My appetite returned just as Antoni showed up as with some wonderful fish caught in the Caspian Sea by him and cooked by him. The taste of that meal convinced me I was on the way to recovery. He brought me up to date on all the events that took place following our mass arrests. I listened tearfully to the litany of friends who had survived, and of those who hadn’t. I was transferred to the hospital in Teheran where Lusia Madalinska, my mother’s half-sister, visited me. I was sure that she must have perished in the harsh labour camps of Archangel where few survived. And then the predication of Moses, so long-ago and far away, floated into my mind, about “travelling to where there’s few women and many men, and being sick here once more.” And so here I was in the Polish Army full of men–and having survived typhoid fever!

Polish Orphans

I recuperated with my father in Civilian Camp No.1 in Teheran. There were four such camps with several thousand Poles. I started to teach elementary classes in the orphanage school equipped with a copy of “With Fire and Sword” by Henryk Sienkiewicz. The children, many of them orphans, were eager to learn and even tried to teach themselves under palm trees amid ancient ruins, with a newspaper or a letter that survived a trek of thousands of miles. I was still recuperating

from typhoid and my head was shaved, which fitted in with the many of the children who also suffered the same humiliation.

The British made efforts to find homes for the children and for adults not in the army, but only those with family serving in the Polish Forces in England would be allowed entry there. The United States, Canada and several South American countries were hostile or else put up conditions which were tantamount to a refusal. Kenya, Uganda, Tanganyika and Nyasaland allowed some refugees on temporary settlement. India agreed to take 11,000 children, and Mexico accepted several thousand Poles on condition that they work in agriculture. Eventually many Polish children would make it to the United States, Canada, New Zealand and Australia where they became citizens and parents.

About 74,000 Polish troops and 41,000 civilians were brought out of the USSR through Persia. But those were the lucky few. Of the estimated 2 million Poles deported into the USSR, about half perished, while hundreds of thousands remained in the prisons, labour camps and collective farms. And the deportations of Poles by the Soviets would resume in 1944-45 and continue under Stalin after the war ended. The United States and England turned a blind eye to the genocide being carried out against the Poles–and one must accuse them of complicity in war crimes, such as the forced return of people to the Soviets. Contrary to Allied propaganda, totalitarian murder did not end with the defeat of Hitler–it merely consolidated Stalin’s reign of terror.

Ahvaz – To India

I was transferred to a transit camp at Ahvaz, 90 miles from Khorramshar on the Persian Gulf. Refugees arrived by regular train and were shipped in box-cars to this port where they set sail for Palestine, England, Africa and New Zealand. I continued teaching in a makeshift school under a tent. Two children, a brother and sister, ages 6 and 8, were typical of my students. Their parents were presumed dead and we weren’t even sure of their last names. They spoke a mixture of Polish, Ukrainian and strange words learned on the steppes of Uzbekistan. They were excited about heading to the port and a new life. Alas, they would never make it, succumbing to dysentry.

On May 8, 1943, my father and I were loaded aboard the SS Kosciuszko, a Polish luxury-liner now in war service. There were over 4,000 adults and children housed in cramped quarters awaiting transport, and we were elated at getting out of these conditions. But we had mixed feelings about our destination, a place that Poles only read about in adventure stories: the continent of India. (I recalled the insight I experienced in the prison cell in Dubno, about being allowed to experience amazing things!)

The last sight of this chapter of our lives was a shoreline of palm trees, as we entered the calm waters of the Persian Gulf, bound for Karachi, India, on the banks of the Indus River, home to another ancient culture. It was beautiful weather, and my father and I quickly made new friends among the Poles aboard, including the crew and officers. What awaited us in India?

Christopher Jacek Gladun was born in 1951 and grew up in Canada to where his family emigrated from England as displaced persons. Sadly, Chris died in Toronto in March 2003. He held a diploma in Journalism from the Niagara College and a BA in Polish Language & Literature from the University of Toronto. Chris also acted as interviewer and researcher for the documentary film “Rescued From Death in Siberia”.

This content is now maintained by the Kresy-Siberia Group, which Chris was a charter member of and which is taking his website and his research work forward.