The Letters of Jan Sulkowski

Jan Sulkowski as member of the Krzemieniec Voluntary Fire Department.

Jan Sulkowski in NKVD photo: his teeth were knocked out by interrogators….

About Jan

Jan was born in 1886 in Ostroleka, Poland, which was then part of Czarist Russia. He studied business in Kiev where he learned Russian, and where he met Natalia Timofiejew, the daughter of a Professor of Philosophy. They wed in 1911 and had three children: Janina (1914), Czeslaw (1917) and Wanda (1925).

Jan was Director of Trade for a coal mine and smelter in Jekaterynoslaw, Russia from 1915-1919, until the Russian Civil War. A number of Polish engineers and employees, including Jan, commandeered a train, and with the help of theatrical military costumes, escaped with their families to Warsaw in a newly-independent Poland.

In 1920 the family moved from Warsaw to Kraków where Jan was Director of Government Shipping on the Wisla River until 1925. Between 1925-1932, they resided in Torun and Porebe while Jan was Director of Purchasing for an American-owned factory, until the Depression claimed his job. Jan then moved his family to Krzemieniec in south-eastern Poland where he was appointed Secretary of Krzemieniec County, a position he held into 1939 until removed by the occupying Soviets. Both Jan and his family were active in the community, particularly with the Krzemieniec Lyceum, known as the Eton of Poland. Jan even delivered budgetary reports from the Lyceum radio.

Jan was arrested by the NKVD in March, 1940, and underwent brutal interrogations in Krzemieniec jail. His daughter Janka was also likewise imprisoned for underground activities. In July, 1940, Jan was “convicted” by a Soviet court for such crimes as “associating with kulaks” and “speaking of the low quality of products of the USSR,” and sentenced to five years in the labour camps. Jan’s Trial Meanwhile his wife Natalia with their two younger children, were deported to Siberia, where they would remain till 1946. Jan would never return to Poland nor see his wife and youngest daughter again.

Jan would spend time in a number of prisons and camps, where he was tortured and robbed, and where his already-fragile health deteriorated. His life was saved by a kind doctor, and by his release in September 1941 during the “amnesty” given to Poles by Stalin who needed them in his fight against Nazi Germany. After a number of adventures, he found himself in an Invalid’s Hospital in Bukhara, in Uzbekhistan, USSR, where he helped the sick and orphaned. Here in 1942 he was reunited with his daughter Janka, released late from the Gulag. Janka’s Memoirs

Jan left on the last ship from the USSR to join Janka in freedom in Persia, and together they moved to India, where from 1943 to 1948, they worked for the Polish Ministry of Education and the Polish Red Cross. Jan conducted the Business School in Valivade and was Director of the Cooperative. However his health would steadily deteriorate, exasperated by the climate and the strain of thwarted attempts at family reunification, and emigration. In 1948 Jan and Janka arrived in England to be reunited with son Czeslaw (who had been in the RAF) and other relatives. On July 20, 1948 Jan died at an army hospital, and is buried under a tombstone with a misspelled name and incorrect age.

About Jan’s Letters

Correspondence ranges from postcards of a few lines to long letters with detailed information, the majority addressed to his wife Natalia in the USSR and later Poland. Letters written from the prisons, kolkhozes and hospitals, chronicle Jan’s difficult captivity, and his brushes with death, as well as capturing the human misery under Communism. An accountant by profession he was meticulous in calculating the costs of living–and of dying. His dry sense of humour, as well as strong religious convictions, permeate his letters…even as he records the deaths of strangers and loved ones.

His letters from Persia and India are alive with descriptions of life in an exotic and demanding country that Jan never imagined he’d visit. But the overriding thrust was family reunification, and a desperate longing is evident in every page. Jan had many plans and schemes which he enthusiastically outlined in great detail–only to see them all fail. Few countries were willing to accept Polish refugees, and Natalia and Wanda would remain trapped behind the Iron Curtain. His words though full of grief, never became bitter. Unable to see his wife and two children, he faithfully dispensed fatherly advice across battle fronts, censors and shifting political lines. His last written line was to his now-adult daughter, whom he last saw when she was fourteen: “Wandulinka, I must have a letter from you!”

One of Jan’s first letters to his family since his release from the Gulag. His wife Natalia was unable to get any word of his fate for a year and a half–and had herself been deported to Siberia with two children. Jan paints an amazing picture of his life and death struggle in the USSR, thanking God for protecting him, even as he agonizes over not being with his loved ones.

September 14, 1941

Turynskij Sowhos

Sverdlovsk Oblast, USSR

Natalia Sulkowska

Nowyj Suchotyn

Kazakhstan, USSR

My Beloved!

The history of my deportation is as follows: from March 22, 1940 to August 17, 1940

I was in Krzemieniec jail, then further through Tarnopol, and in very difficult stages to Starobielsk where from September 29, 1940 to August 17, 1941 I was in better conditions. Then I was released from “corrective labour.”

Then finally transport north to Karolina Oblast. During this time my health was very bad–I became so weak that I was preparing for my life’s end. And so it would have been all over if not for a woman doctor who took pity on my exhausted state, and let me off from certain work for a month, and took special steps to fatten me up. For the first time I was able to remember the taste of meat (other than Auntie Malinowska’s packages) and the taste of sugar and fresh fruit (plums) as well as receiving a daily compote of wild morels. This rich food put me back on my feet despite the fact that I was sleeping on bare planks–but I had gotten used to that.

Living in barracks with 250-1000 people completely shattered my nerves. These “people” were horrible and there were times that this violent company caused me to stay silent for weeks at a time. In Starobielsk the overcrowding was terrible and full of horrid people: murderers, thieves, professional con-men, and political criminals who weren’t much better than the others. The level of swearing was so awful that even repeating a small part is not possible for me. Stealing was a constant phenomenon–they took anything that could be stolen: pieces of clothing, bread, sugar etc. on a daily basis. There was such a plague of fleas that a person would do anything for even temporary reprieve. One of the methods used was the woszebojka, an apparatus near the steam bath which used steam at very high temperatures to kill the lice and parasites in your clothes–but it also ruined your clothes. My suit was utterly ruined, but more about that later. Of course normal food was not available and scurvy and avitaminosis were a constant phenomenon–half the people suffered from chicken blindness. Avitaminosis gave me a whole bunch of sores, big and small, which didn’t heal. Here in Karolina my hands were infected with twelve sores of which today three are still festering.

In Karolina and later in a nearby lagier[1] from Kasalmanes Station everybody had to work–but thanks to that women doctor of which I wrote, I was joined to an invalid’s brigade and escaped hard labour. There was peeling bark from elm trees, loading wagons with wood, carrying and sawing wood; this qualified as “light” work as it didn’t figure into norms and quotas. In any case I didn’t work that much as I was quite often let off by the doctor; at most I worked 1-3 hours a day carrying burned wood, planks etc. After this beautiful (for me!) experience, I was transferred to regular conditions of working in the forest and eating from the No.1 kettle. The food was even worse than poor: at 5 in the morning watery soup, 3 leaves of cabbage, and 2-3 potatoes–and then 12 hours of work followed by a meal at 6 of soup and a piece of salt fish. Cutting wood, carrying planks and firewood, digging, as well as fixing roads was awful work, but at least it was in fresh air and in the forest we picked berries, huckleberries, raspberries and hawthorn, which I learned is edible and even tasty after the first frosts. I must add that during this time I hardly smoked.

All these better conditions however did not prevent my weakening again, and at the moment of my freedom on September 6, 1941, I was in a state of exhaustion. Freedom considerably helped me psychologically as well as with sustenance, but it also put me in a series of hard situations of which the worst was my stay in the Karolina Rail Station (in the rain) of 5 days waiting for a place on the train, and finally a day’s stay on the streets of the city of Swiezdlow and 24-hours on the streets of Turinsk. In 7 days I slept at most 25 hours in terrible conditions.

Presently I am near Turinsk in a place called Nazarowo where temporarily for an indeterminate time, I have become a bookkeeper for an agricultural farm belonging to a large sowchoz.[2] One night I slept on the floor of a fire station (what an irony!)[3] and the next in my “office”on a table–they’re promising improvements. Food on the other hand has improved radically. The bill of fare in the canteen is cheap and plentiful. Yesterday morning I ate three portions of pea soup at 11 kopecks=33 kopecks; for dinner I had soup with real meat for 1 ruble 14 kopecks, and delicious potatoes with butter at 40 kopecks. That evening for 31 kopecks I dined on kasza manna[4] all the portions quite big. This morning I only had one bowl of pea soup for 11 kopecks. I also received some milk and I boiled myself wheat coffee with milk and bread. They give plenty of bread (black) of 800 grams daily at 7-8 kopecks. At this rate my daily “menu” costs are 3 rubles 50 kopecks, and added to my tobacco (self-rolling), my monthly expenditures are about 150 rubles. My pay is about 280 rubles a month which leaves 130 rubles which, above all else, I will use for clothing if it can bought.

I could actually have travelled to you for free (a 2-day journey). But I was afraid, and still am, that I wouldn’t find work there, and the lack of correspondence (your most important letters I never received) fill me with dread that even not counting my stomach, it’s touch and go for you regarding food. My heart told me to go to you, but my mind persuaded me to wait and get some money and clothes. If work is available there, I’ll certainly come (a ticket costs 60 rubles). At this time I’m quite weak–my head is foggy so that it’s hard to work. I found some good work here and I don’t want to change it until I leave, and only after I rest up and get some decent clothing. If you still have the fufajka[5] which you smuggled for me, then send it to me along with machorka[6] (if you can spare any).

I’ve never written such a chaotic letter before–it’s very hard to concentrate my thoughts. If I make it until the frosts and winter comes, then I’ll send you bread (dried) and meat. If you still have anything left of clothing, then send them (the situation with warm pants is bad)–and I’ll send what money I have. In jail thieves robbed me repeatedly–jacket, gloves, earmuffs etc–but the greatest harm they did to me was the theft of my eyeglasses…I’m half-blind. I have borrowed glasses on my nose but of course they’re farsighted and not for my eyes. And it will be an added cost to buy glasses, if I can actually find proper glasses for my condition, which is doubtful.

Soviet Affidavit attesting that Jan Sulkowski worked as a bookeeper in Czumbay from Nov.12, 1941 to Nov.16, 1941.

Certain thoughts which run through my mind both night and day, I’m actually afraid to put to paper. The first of them is, will I be able to live long enough to be able to hug you? When will I be able to see you in normal conditions? When shall I be able to rest a bit? Will there be a time when I’ll be able to forget all the terrible things I lived through? What about Janka? Every thought about her is like a blow and it weakens me horribly. I can only send my sighs to God, and pray to my patron saint, Jan Nepomucen, and to your beloved Saint, and this quiets me. Without the constant protection of these two saints I wouldn’t have survived all that which I lived through–and I yet have to live through more. God’s protection is so obvious to me that I carry absolutely no doubts. When you read this letter written in such terrible times, be thankful for the series of miracles that I received.

Returning to matters of clothing, it’s simply a miracle that I took my fur coat–for the 17 months that it’s survived, it’s in not too bad shape; on the other hand from my suit only the jacket remains and it’s all in patches and tatters. The pants I can no longer use and I wear the pair which Pius Zaleski[7] gave me and they also are in a sad state. The soles of my warm boots are still good but the top is in patches. I have something resembling a suitcase: a wooden box that’s heavy but looks good. My watch disappeared somewhere in the NKVD administration–all I have is the receipt. The rest of my things including my gold have gone missing without a trace. If you’re going to send my fufajka get Czes to also make me suspenders from rubber.

Wandulka–what is she doing? How many nights did I toss and turn thinking about the four of you! About the bad things that I did to you…about all those things that happened because of me, and not because of me. If only the good old days could return–how our lives would be different and better. If only we can endure! My God!! It’s very hard for me to write this letter; I have so many questions in my mind but I’m afraid to ask them as it’s just too horrible.

I must list the “intelligentsia” which is represented here: a) an agronomist and former very rich landowner, b) an artist-painter, c) an engineer, and a few lesser accomplished individuals. As far as practicality goes I stand the best–but I’m keeping myself up only on the surface. My nerves only sometimes are calm. Kagan from Krzemieniec is here and has shown himself to be a complete cad; he ignores the fact that we once greatly helped him and his family. For me he’s totally without character and I’ve almost completely severed my relationship with him.[8]

Write me exactly what the children are doing! What you’re doing! The censors aren’t to be feared, but it’s better not to write about terrible matters, and why should we? We know and understand many things without writing. Instead write me all about your financial matters.

Geographically Sverdlovsk Oblast borders with Omsk Oblast which borders with Kazakhstan. As to plants and climate, it’s bad here: the earth grows oats, barley, potatoes, rye is worse but there is some as well as wheat. There’s much horned cattle (our State farm has about 1000 head of which 600 are excellent) but you can’t get butter here, only in the local towns at 25 rubles a kilogram. Milk also can be bought privately at 2 rubles a litre. On the other hand the farm sells milk with pieces of lard for 10 kopecks. I haven’t tried that milk yet–I shouldn’t drink it as it’s bad for the heart, and my heart is in a bad way. The weakening of my heart has been acute, though my feet haven’t started swelling as has happened to many of my friends here. I feel only a great shudder when walking and especially when carrying something heavy. Presently, to fill the communal storehouse, all the office workers were sent into the fields to gather crops and later the same for potatoes. But I talked myself out of physical work and this was accepted. It’s good for me in that the rains are falling and I would ruin my fur and boots, and without fur I wouldn’t be able to walk to the washroom in the winter.

Mamusienka write me a detailed letter about what’s happening with you. Send a big letter (covered in an envelope) and continue to send postcards at least once a week. A few days after this letter I’ll send a postcard. I forgot to add the description of the climate–that there is dust here in untold amounts which gets into everything–nose, eyes, ears and under your clothes. The people wear cheap black gauze but even this doesn’t give 100% protection. The city of Turinsk has streets made from wooden blocks and wooden sidewalks are everywhere. Sverdlovsk is a big city in the style of Lwów with many nice houses.

Kisses, Your Father

[1] A concentration camp.

[2] A large Soviet state-run farm.

[3] Jan had been a member of the Krzemieniec Voluntary Fire Department.

[4] Cereal/groats.

[5] A heavy quilted winter coat.

[6] Coarse leaves of tobacco for rolling–cheaper than cigarettes.

[7] Pius Zaleski a family friend and one of Janka’s underground members, died in Starobielsk shortly after.

[8] Jozek Kagan, a Jewish neighbour whom Jan often helped, but who became an NKVD informer and did Jan a great wrong.

Contact between Jan and his family is difficult due to censors and other roadblocks placed by the Soviets in front of Polish refugees struggling to enter the Polish Army and leave the USSR. Jan recounts his wanderings and adventures in the USSR, and his life in an invalid’s hospital.

June 13, 1942

Invalid’s Home,

Bukhara, USSR

Natalia Sulkowska

Kazakhstan, USSR

My Most Beloved!

Yesterday by chance I received your address from a woman in passing, who also gave me the first news of you in a long time. I think I’ve used up every possible way of finding you, all with no results. I wrote to different NKVD offices, to police stations, even to the director of some electrical power station, but nothing, no answer. I wrote to the army without results. Today I telegraphed you so I could get an answer from you quickly as possible. Constantly I think about what’s become of you, and it chases away my sleep.

Polish survivors of the Gulag

My history is filled with wandering. In August of 1941 I was released from a labour camp in the north which had been very hard on me. Made it to a solkhoz in Turinsk–my first job–quite hard conditions–exhausted, but not hungry. I wrote to you, there were projects–but they called me to the army–barracks in Sverdlovsk and later supposedly off to Buzuluk (Polish Army) where they transported us without end in horrible conditions toward Tashkent…but in reality they took us to Amu Daria. From there in even more horrible conditions on steel barges to Nunus–by truck to a kolkhoz–I escaped (35 kilometres walking at night) to the city of Czumbaj. I was completely exhausted. Then a hospital out of which I wrangled myself–got a job–I started to regain my strength but after a few days a new order–immediate transport (we thought to Iran). Nunus once more, steel barges again–and Dantesque scenes: corpses, corpses, corpses! From the barges to trains–finally we’re thrown off at Kizil-Tepe–a kolkhoz. I arrived half-conscious–then 6 weeks of dysentery–simply a miracle that I survived. Escape from the kolkhoz–thrown from the train 4 times–made my way to Kermine–and the Polish representative Wezek (remember that thanks to him I then went to the Invalid’s Home in Bukhara on Feb 7, 1942).

I’ve been here five months. I’ve revived. Presently I feel considerably better but still quite far from my state before Sept 1, 1939, and even then I wasn’t healthy. But at least here I have a bed with a mattress, a warm blanket, and something I can call a pillow; also three hot meals a day (much of it water), a bath, shaving, a mirror, walks etc. Since May 1, I’ve been a bookkeeper for the Polish Protection Agency who have a home for invalids, a convalescent home and a protection agency for children–in total some 300 residents. I earn 250 rubles a month + living quarters + food + extra food products + laundry. It’s getting steadily better except for the heat waves reaching 50 degrees in the shade–at noon everything dies down. Our conditions are pretty good except for the cost of living. From my clothing only my fur remains, destroyed as it is but still wearable; nothing else remains of my old clothes.

I have to tell you how I wandered to Nunus and how they accepted me with open arms. Thanks to the great protection of Mr Wezek I survived the journey from Nunus to the kolkhoz. They opened their hearts to me. When I can I will do my best to repay them. Here in Bukhara I met Stadnicka and Kagan who looks like a candidate for the great beyond. I received a letter from Lilka Zurawska and am sending you her address. There is a Polish agency with Meze Zaufania[1] in this region who warn me that letters never arrive–I hope that this one will make it. I know that Czesiek is in the army but without official rank. You should be able to get army relief–you should write and notify the army in Yangi-Yul or to the main headquarters of the Polish Army. What about Jancia? I just had a thought that she might be in the army.

Write me often, Kisses,

Your Father

Jan agonizes over the lack of news about the fate of his eldest daughter Janka, who disappeared into the prisons and camps of the Gulag, and is feared dead. He discusses plans for reunification with Natalia.

June 20, 1942

Invalid’s Home

Bukhara, USSR

Natalia Sulkowska

Kazakhstan, USSR

Beloved!

It’s already the third letter I’m writing to you and I’m wondering when I’ll finally get something back from you. Your first telegram arrived June 17 in such a jumble that it’s difficult to figure out. The other “air mail” one I received on June 18, and so I answered both telegrams at once, notwithstanding that I had already telegraphed you on July 13–yet it seems that by the 17th you hadn’t received it.

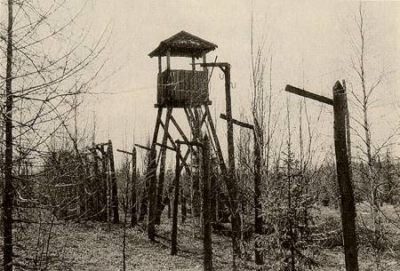

Gulag Tower

I already wrote that I’m slowly bouncing back–my health is getting better, though I am very skinny and my nerves often refuse to obey me. My heart is not even that bad: there’s little reason for it to be acting up except for the nicotine and the heat. My mental faculties, in terms of rapid work, haven’t lost anything and maybe are even better than in 1939. But physically I’m weaker of course, and quite markedly; it’s difficult to walk and I don’t walk much, and luckily I don’t have to. I do smoke a lot–real tobacco lately, an expensive pastime but without it I would go mad. What can I do?

That I don’t know anything about Janka is gnawing at me. In Czumbaj on the Aral Sea I met one of Janka’s companions in misery, from the lagier, but unfortunately I don’t know which one. She said that Janka was not freed along with her, but later. (And was she freed?) And that she was keeping very well except she lost much weight. Later a priest from told me that during his time in Buzuluk he met a Janina Sulkowska who was in the hospital for some time, and that she was accepted into the Army, to the eighth platoon. I wrote to Buzuluk without getting an answer and twice I wrote to the General Headquarters in Yangi-Yul–no reply.

At the headquarters I also asked about Czeslaw–no results.[1] Letters don’t arrive–is it the same there that with so much work they can’t answer? I asked about you at your old address and later I wrote to Stadnicka who I happened to meet here. I also wrote to the Director of the Electrical Works, to policemen, to theNKVD, to the Militia, to our newspaper in Kujbyshev–nothing! Lilka Zurawaska was searching for me and Jancia in the newspaper. She found me as I read it and answered, but Lilka knew nothing about Janka or you.

Imagine to yourselves that in Bukhara I came upon a man lying in the street. I bent down to help him up. He whimpered and addressed me in Polish: “Mr Sulkowski, help me, I’m Kagan from Krzemieniec, Josek Kagan and I’m sick.” I wrote that I met Kagan here; he was in jail with me in Krzemieniec and later in Starobielsk, and we were together in the lagier as were his children. My surprise was very great, but naturally I recognized him as we had after all shared the same house for some time. I didn’t have, and I don’t have, anything to be grateful to him–rather it is the opposite. My memories of this man were bad: he was a drunk, a gambler, I had heard as he beat his wife and children, and later he had even been a NKVD agent, but at this moment he was a sick person. I took him to the hospital which was overcrowded and they refused to take him. I convinced them with the backing of rubles and they accepted him and even a bed was found. When I returned to the orphanage I had to change my clothes and fumigate myself as Kagan’s fleas were crawling all over me and I was afraid of typhus. Later I learned that he did have typhus and had died from it. But at least he passed away in a bed like a person and not in the street.

I was sent to the Invalid’s Hospital on February 7, 1942 and lived through my hardest time here with typhus–and dozens of corpses. It was specially difficult for me as I was performing the duties of an orderly and drove patients to the hospital while I had a fever etc. The sick were grateful to me–nobody (not even the doctors) could believe that I didn’t have any medical training. My supervisory doctor always declared that I myself was incurable but that I cured many others (of course not of typhus).

I want to see you so much and hold you to my heart so badly that I scream with pain at the thought that I can’t! So write to me as quickly and as much as you can. There’s censorship of course so it’s best not to glue or sew the letters.

I give you big, big kisses and can’t wait for yours,

Your Father

Death was not very far from the Polish refugees–especially for the sick or weak, and children.

My Dears!

Jan Sulkowski (himself very sick) among his beloved orphans.

I feel an urgent need for more contact with you–I really haven’t yet received anything from you (except the telegrams which are full of worry and a stranger’s words). Don’t expect to get my first letter too quickly as communication between us is very far and difficult.

The heat waves are awful–which terribly affects us who are unacclimatized, and most of whom also have dysentery. Children are dying like flies. The little cemetery for children near our nursery is growing daily–22 new crosses since the middle of April, not counting those who died in the hospital which is about a dozen kids. Usually the process is as follows: the child returns from the hospital after being cured of dysentery, and then dies after 2 or 3 days–it simply extinguishes itself as it grows weaker and weaker by the hour, until there’s only a corpse. With adults it’s not much better; there’s no medicines, no proper nourishment (a complete lack of animal fat and sugar). And many are dying, some say because it’s our own fault–but at what fault is a poor, nervous old man? My neighbour died today (the second bed from me). Chronic dysentery that weakens the system until finally…death. They were to take him to the hospital today but he didn’t make the trip–in fact he went on a much longer journey. His name was Stanislaw Hrehozowicz from Wilno. In life he was impractical and so he had to die.

But you also can’t be too practical. Today in the name of the Delegation, I had to throw an overly practical individual out of the Invalid’s Home. A Pole who was stealing all he could to live–and he was living a great deal. For sure it’ll end bad for him, as without work and food he’ll perish unless he keeps stealing, and that too will be bad. But so much for this philosophizing–life is life and we search for those forms which best adapt to conditions and surroundings. I “won” in this invalid’s hospital, whether just by coincidence or through personal struggle–but enough that I “eat” well while others feel lousy. In a few days I’ll be moving to a new house, where there will be an office and my “private” room. Finally I’ll be able to sleep all by myself in a room without smelling the stink of others. Small thoughts and petty incidents fill my days–and maybe this is good for me as I don’t want thoughts to take me too high and keep my nerves taut. I have to admit that I’m weak–I’m in no state to even react to the swarming flies of which there are many here.

I’m awaiting your first letter in which I hope to find answers to hundreds of questions which will help me in making future decisions. Natusko write me about everything, above all concerning your present situation and then tell me about what befell you previously. Above all you must keep constant contact with the army outpost there and with your Army Family.

Big, Big kisses,

Your Father

Jan describes the dramatic reunion with his daughter Janka released at a later date from the Gulag–each assumed the other had perished A family reunion is planned, but will never materialize. In just a few weeks, Jan and Janka will leave for Persia, and later India, with the Polish Army.

August 2nd, 1942

Invalid’s Home

Bukhara, USSR

Natalia Sulkowska

Nowyj Suchotyn

Kazakhstan, USSR

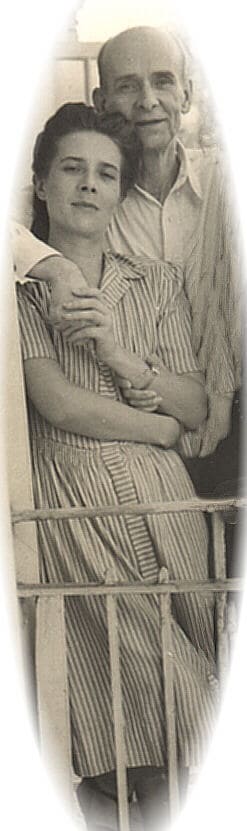

Janka on the day of her release. March 1, 1942

July 31, 1942 will be a memorable date for me: Janka suddenly appears! Janka is healthy and strong–simply fat. And very well dressed. For a long time I had not cried–but the tears I shed were ones of joy and happiness. I didn’t write anything to you about her, but I was of the same opinion as you: that Janka was no longer alive. They had kept her a half year longer than the others. She was also of the opinion that she would never leave that hell alive. Thank God the Highest that Janka was resurrected from the dead.

I think that know we’ll be reunited–or at least we’ll go to where it’s better. You and Wanda have rested and should get ready for the trip here. Yesterday a telegram from an army outpost arrived about work but it will costs a few thousand at least to go. Sell everything that you have as you can buy things here at half-price. If there’s cheap gold there, then buy it. Yesterday I received an advance of 100 rubles for you, and gave 40 rubles for the trip. As well I received milk and 2 kilograms of meat. Yesterday we telegraphed you but they wouldn’t accept the telegram at your terminal. I don’t know what’s going on!

Big Kisses for you all,

Janek

Despite his poor health, Jan is taking care of orphans of the Invalid’s Hospital awaiting transport from the USSR to Persia.[2] They will make it to freedom across the Caspian on the last ship to leave the USSR, and Jan will join his daughter who comes down with typhoid fever.

1942 (in transit to Persia)

USSR

Janina Sulkowska

USSR

My Beloved Daughter!

I’m not doing too well–yesterday I had such terrible pains in the area of my liver and appendix that I howled for two days. The pain was so acute that nobody slept in our tent for two nights while I moaned. I’m feeling better today but I’m so weak that I can hardly walk which is why I didn’t come to visit you and postponed it till tomorrow. Then they informed us today that tomorrow at 4 a.m. we’re leaving so I’m writing to the Polish Red Cross The doctor (a lousy one!) gave me this and that, but nothing helps.

We’re going to Teheran, and after a short stay there we’ll be going to a place some 350 km past Teheran–supposedly the most beautiful place in Persia. How is your health? I trust it’s good. I’ve gotten some disease but so far I’m in good spirits. I’m going to try and scrape through and reach Lusia, and in this way to communicate with you. I have news that all the Polish armies will be concentrated near Bukhara–is this news worth anything? I don’t know, but I hear that Czeslaw is going to France from the USSR; there’s to be some 6,000 transported through Aszphat including army families. Maybe ours will be going as well.

I kiss you my daughter,

Your Father, Jan

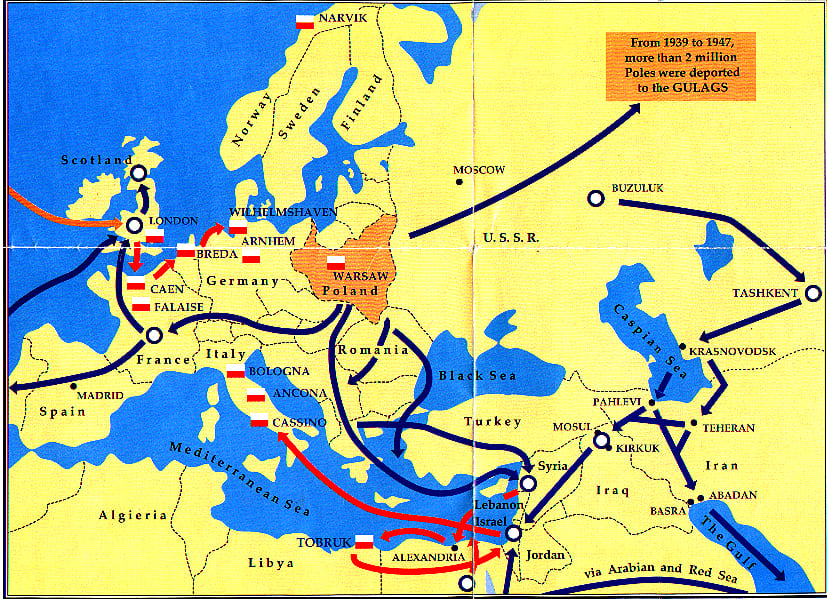

Polish Routes in WWII

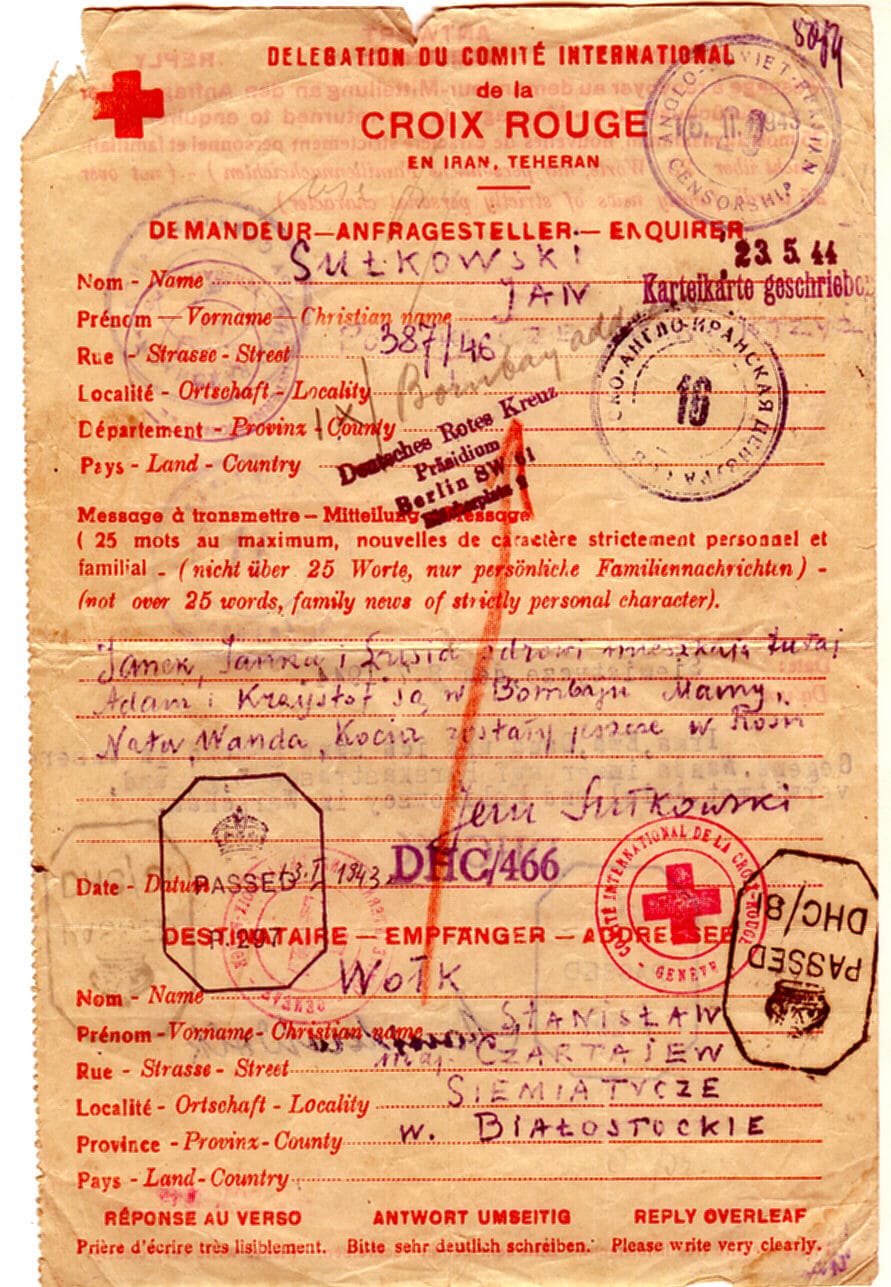

Red Cross message sent by Jan to brother-in-law Stach Wolk, in Nazi-occuppied Poland. Subject to Anglo-Soviet censorship as well as the Red Cross of Nazi Germany, it was quickly out-of-date. “The Mothers” and Kocia died in the USSR. The reference to Adam and Krzystof being already in India was a ruse to keep them out of Soviet hands and smuggle them out, which never materialized.

Teheran, Persia

Stanislaw Wolk

Siemiatycze, Poland

Janek, Jana and Lusia are healthy and are living here. Adam and Krzystof are in Bombay. The Mothers, Nata, Wanda, Kocia remain still in Russia.

Jan Sulkowski

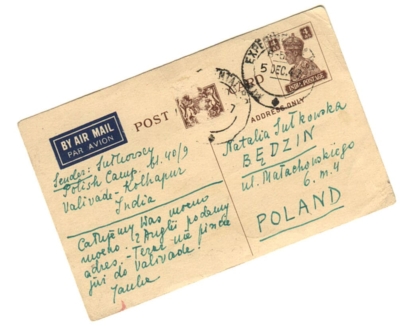

Stach’s answer to Jan reached him in India in May, 1944, and was also out-of-date: Aniol (Grosicki) would be killed in the Warsaw Uprising and his wife murdered by the Nazis in Pawiak Prison. Four months after his reply, Stach was imprisoned by the Soviets.

Stach Wolk

Siemiatycze, Poland

Jan Sulkowski

Bombay, India

Irma, Ewa, Dana unde ich sind gesund in unsere Gegen. Wanda immer auf Barskastrause 5 gesund. Aniol und Malinowscy in Warschau.

Stach Wolk.

Jan and daughter Janina lived in India from May, 1943 to February, 1948, working for Polish aid organizations. Communications with Natalia in the USSR was difficult during the period of 1942-1945.

July 14, 1944

Bombay, India

Natalia Sulkowska

Kazakhstan, USSR

Dear Nata!

We only now received your postcard from Nov. 20, 1943–it travelled for a long time through Teheran and Africa. We’re healthy, though the climate is very bad for Europeans. I was sick for 3 months but presently I’ve almost gotten over it. Janka is also feeling good. Janka and I work in the same office; we live at Bizonska’s who has been here for a long time–her husband died in Poland but she was able to escape Hitler.

Jan Sulkowski (left-back row) at Civilian Camp No.1, Teheran, which housed Polish refugees, greeting an Iranian Minister.

A friend of ours is organizing the sending of packages to you. As far as we know 13 packages have already been sent. Further shipments will be sent from Palestine if things work out. Czeslaw and Lusia are in the army–in London. Lately we haven’t received any news from them. They’re healthy and doing all right, though they’re both serving as ordinary soldiers. Irma, Stach and the girls are alive–we have no further details from them.

Big kisses, Janek and Janka

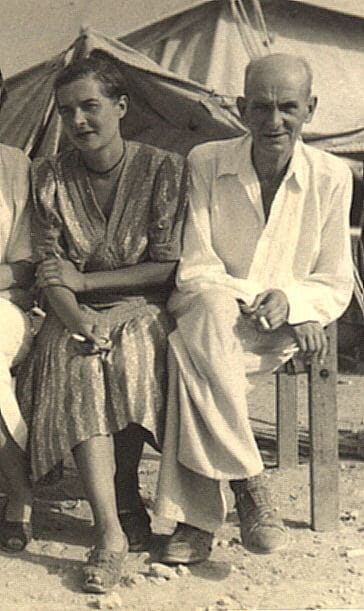

Janka and Jan shortly after arrival in Karachi, India, June 13, 1943.

Natalia and Wanda returned to Poland in 1946, now under Soviet occupation. Plans for them to join Jan in India, or for Jan and Janka to return to Poland, dimmed, even as Jan explored emigration to Australia, Argentina, the USA, and other countries which did not want Polish refugees. Jan gives a synopsis of their stay in India, and reflects on family losses, while promising to send care packages to Natalia who sells some of the items, including medicines, on the black market.

September 1946

c/o Polish Red Cross

15/17 Queen’s Road, Bombay, India

Natalia Sulkowska

Kazakhstan, USSR

Janka has already expressed our feelings of pain and longing. I assure you that we’ll do everything possible to better your lives. Unfortunately our possibilities are severely restricted by the great distance; from India we can’t send you anything with the exception of cigarettes–but we’re making certain efforts to send you parcels from other corners of the world, which of course takes time.

I regained Janka in 1942 in Pahlevi, Persia, but my joy was muted as I found her sick with typhoid fever, and it was only weeks later that we were reunited in Teheran–and we have been together ever since. Meanwhile she brought to Persia not only typhoid but also malaria with which she wandered all the way to Bombay. I’m so happy that I found Janulka–I just can’t imagine an existence without her. For four years now we’re living inseparably: at first I took care of her, but now she’s my protector.

We had been working all that time with strength and vigour. I finished work in December of 1945. Janka continues to work but I think in October we’ll be leaving Bombay and we don’t know if Janka will be working in the Polish settlement, while I still won’t be able to work. Our stay in India, this legendary and beautiful India, was paid for with our health. Many have thus paid for all sorts of diseases that Europe can’t imagine. For half a year now Janka has been fighting parasites that are destroying her intestines and digestive tract–she looks thin and wilted. Lately there’s been hope that her sickness is ending but certain doctors are of the opinion that it might end only in a better climate. My bronchitis took a bad form here in India–and on top of that on June 8, a clot passed through my heart. Only intensive medical help revive me after an hour’s unconsciousness. After this I lay for 20 weeks in hospital. Presently my heart condition is being treated but my bronchitis is aggravated by the terrible heat (over 40 degrees) both day and night without a break which bothers me greatly. I’m weak from the treatment and from lying in bed. The Indian climate is deadly for Europeans for any extended time.

Stefan Norblin (top) and Lena Zelichowska with their son in India, shortly before emigrating to the USA. Sadly, they would both commit suicide in San Francisco

Dear Natausienka, one thing we can confirm is that our children are truly good children. Janka, though she is starting her fourth decade, is a better daughter than she even was before. Czeslaw, who we haven’t seen for so long and whom we only know through correspondence, is really a wonderful son and brother, and an honest and righteous person. Let this be a solace in our time of shared suffering. The painter Stefan Norblin and his wife (the famous actress Lena Zelichowska) left a month ago with their son for America. The doctors advised them that this was their last hope against the onslaught of tropical diseases. Mrs Bizonska, and her daughter Liza who divorced her husband two years ago, are living here but are planning to go to Australia at any moment. The elder Bizonska, who three years ago was full of energy and was running a boarding house in Bombay where we lived, has today completely lost her health. Wandulinko you are right that it’s not fair that we have to live in separation, that for so many years we haven’t seen each other and that in reality we knew nothing of our lives. It is an injustice we are are in exile under conditions that are evil and heartbreaking for us. But what can one do? A cataclysm unprecedented in History smashed our little nest and thrown us on separate roads!

However we must admit that in comparison to many others, our fate was, and still is, not that terrible. If we look at the utter annihilation of millions of human beings, of millions of families, we have to admit that our families came through the holocaust with smaller losses than others.I’ll just mention a few: Minister Juliusz Poniatowski lost his wife Zofia in Palestine, and his daughter Basia, was murdered by the Germans in the Warsaw Uprising-he’s left all alone in his old age and sick at that. Jakub Hoffman lost hiswife in Teheran. There are people in our Polish settlements who’ve lost their whole family, 5-7 members.

Czeslaw had a fairly hard experience. He still is in the Air Force but was unable to achieve what he had sought. However this prevented him from putting his life at great risk, as many of his friends did, and of whom death took many in the skies over Germany and elsewhere. He’s still our beloved son and I have the impression that he hasn’t changed at all in the time of our separation–only a few years older. Lusia is maintaining bravely in all respects. We’re aiming at joining them in England; her husband Zbigniew is also going to come. Thus as five we’re going to think and work together to push on with life, but we’re not planning any future projects at the moment. So study Wandulinko–at this moment that is your main task. Help Mama and remember your old father who gives you

Big, Big kisses,

Jan

Jan describes the conditions of life in India for him and Janka, and other Poles (an amalgam of excerpts from letters written from 1946 to 1948)

December, 1947

c/o Polish Red Cross

15/17 Queen’s Road, Bombay, India

Natalia Sulkowski

Poland

My Beloved!

On the day of the birth of Jesus Christ, we offer greetings from the bottom of our hearts. This is already the seventh Christmas and New Year we’re spending apart!

On the day of the birth of Jesus Christ, we offer greetings from the bottom of our hearts. This is already the seventh Christmas and New Year we’re spending apart!

Bombay, Calcutta, Karachi, have lost (or never had) an exotic Indian character. These are cities that look European with trams, buses and cars. The horse is used for riding while beasts of burden are oxen–and humans. Millions of men in loinclothes, while women wear lavish attire. Funerals often pass by our window (even now!) that sound more like weddings–they shout, sing and play with a jumping beat. The temples are primitive and poor, and toilets are filthy.

To compete in physical work with the Hindus is impossible as their pay is 30 rupees per month–a quota at which a white person will die of starvation. India is a country of paradoxes, where next to Maharajas with incredible fortunes, there are millions who die of starvation.

The white doctors (mostly Jews) earn a lot, but the local doctors, if they distinguish themselves, can also make thousands. But there’s a shortage of nurses, and our Polish nurses (20 so far) are working in 3 hospitals in Bombay and are paid not too badly. Generally Poles are liked here, and if the English were less concerned with us, it would be pretty good.

As to our photos, we are like all Europeans (even if some are fat) and look like plants grown in hothouses: anaemic, but that’s unavoidable. The fruits here are beautiful, but without taste or vitamins–we prefer apples from the north to the best local pineapples. Bananas and oranges are tasteless–sucked dry by the burning sun.

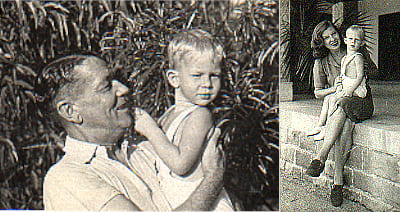

Instructor Jan Sulkowski with his class at the Business School

at Valivade-Kolhapur, Polish Camp.

Presently we’re experiencing (as witnesses) battles between Hindus, Mussulmans and other faiths, with the exception of Catholics who are few. These fights consist of disembowelling each other with knives, or stabbing in the back. The authorities are powerless to deal with the violence. What can be done when in Bombay there are 500,000 people who are considered homeless? Those few thousand murdered bodies out of 400 million, make little impression.

The rains are only during the summer from June to September and are plentiful and daily –everything steams and rots, so that clothing and shoes have to be kept in metal boxes. From September to June there’s hardly any precipitation, while the worst months are May and October when there are heat waves

without a drop.

Nata, your assumption that India is a land of diviners is mistake. There are fortune-tellers wandering about who want to read your palm or sell you a “lucky” rock, the kind that can be bought for a few cents. Supposedly there are Yogis in India, but they are in the south and never seen in big cities.

Big Kisses (and from Janka),

Your old man–Janek

Jan dispenses fatherly advice to his daughter Wanda, whom he last saw seven years ago when she was fourteen–and who is returning to start high school as an adult, while also helping her mother.

March 15, 1947

c/o Polish Red Cross Poland

15/17 Queen’s Road, Bombay, India

Wanda Sulkowska

Biala Podlaska, Poland

Wandulinka, My Golden Child!

Wanda Sukowska as Jan last saw her…

Matula promised to write her next letter very quickly but somehow we’re not receiving it. Instead we got a very nice letter from Auntie Musia in which she writes about you–that you graduated to Class II and with good marks, and that you stopped smoking, for which I praise you and give you big kisses.

If only you knew how much torment I lived through when I didn’t have something to light up; I sometimes came to lowering my personal dignity just to get a cigarette. Those who didn’t smoke had an enormous advantage–I would give away my bread for tobacco which harmed my health. There were incidents where people who were upright and law-abiding, began stealing to satisfy their lack of nicotine, and there were even cases of people going crazy. During 2 ½ years I witnessed many horrible, never-to-be-forgotten, scenes. So never smoke again–don’t put a cigarette in your mouth even as a joke. Czeslaw sent us your photo; whenever I look at your little mouth I imagine a cigarette sticking between your lips, and I truly feel horrible every time. I smoke because unfortunately it’s too late and I cannot but smoke–but I have reduced my smoking to 7-8 cigarettes daily. The doctor also forbade Janka to smoke and she also has reduced her intake to 6-7 cigarettes (she previously smoked 30 or more). It would be marvellous if the example of the youngest of our family would give such good results.

A few days ago Janka sent stockings for Auntie, and a little Hindu God made from sandalwood–just smell it! Next we’ll send you elephants carved in bead; give half of them to Adas and half to Krzys. I’m sending you two dollars in this letter for your postal expense (this is not quite legal but I think that such a trifle won’t cause any objections and the dollars will make it).

Now about you Wandulinka. Your return from “paradise” has to be considered as another instance of God’s Grace. Give the enclosed letter to Aunt Musia. Your darling auntie is your best guide and every piece of her advice is dictated not just by her head, but also by her heart. Darling listen to her words! I really don’t have to write this as I can see from Auntie’s letters that you have realized this yourself, but I still can’t reconcile myself to the thought that you are a grown-up lady Dear Wandulinka, and I still see you as you were in Krzemieniec.

I hold you to my heart with all my strength,

Your Father

Jan discusses emigration plans with his brother-in-law, Zbigniew Madalinki, who as a captured Polish officer, spent most of the war in a Nazi Oflag. Most countries will reject Polish refugees, even as their governments recognize the Soviet-imposed regime in Poland. Most Poles will not return to Poland.

April, 1947

c/o Polish Red Cross

15/17 Queen’s Road, Bombay, India

Zbigniew Madalinski

Angers, France

Dear Brother-in-law,

The Pole in India: a magazine for Polish refugees, for which Janka wrote.

I’m sitting down to confirm that an Indian representative visited us, and that we gave into his hands applications for visas to Australia and New Zealand. He’s going there to discuss the emigration of Poles from India. On the applications, he added that I’m a specialist in raising hens (?) and that Janka is a specialist in haberdashery, and that we’re well-suited for nationalization! Our applications will get to South Africa, Australia, New Zealand. He tried to talk us into Canada, but we’re no longer considering it.

I’m sitting down to confirm that an Indian representative visited us, and that we gave into his hands applications for visas to Australia and New Zealand. He’s going there to discuss the emigration of Poles from India. On the applications, he added that I’m a specialist in raising hens (?) and that Janka is a specialist in haberdashery, and that we’re well-suited for nationalization! Our applications will get to South Africa, Australia, New Zealand. He tried to talk us into Canada, but we’re no longer considering it.

Zbigniew, you are mistaken as to the climate of South Africa–it’s perfectly suited for us. The eastern coast is warm and during winter it’s a place for rich South Africans for swimming. We have news from our Polish sailors who remained there for good.

But South Africa has a fault–the conservative way of life of South Africans supported by money. It’s not “proper” to not own a black “boy” and a black cook. There are riots there paid for by Stalin, but the blacks are so hopelessly lazy that they don’t present themselves as a great danger. One should hope that thanks to these riots, the whites will become less conservative.

All this doesn’t preclude visas for any of the three Dominions. A letter arrived from one of our Bombayans who went to Australia–he says knowing English or having a specialty can earn you a piece of good bread with butter. An abandoned chicken farm costs 300 Australian pounds and to bring it to production, the same again. I calculate that we’ll have 250 pounds plus linen and clothing: 500 pounds in total. And with Czeslaw’s 100 pounds we’ll have enough. If we stay in the city, Janka and Lusia will work as seamstresses or waiters. You and Czeslaw will be mechanics, and I will be a cook and caretaker.

Now about Argentina. There’s no doubt the widest horizons are there–even a shabby garage for fixing machinery will give a piece of bread with slonina [pork fat]. Farm work and cotton-picking is not for us. I already worked in Soviet cotton fields, and if they didn’t feed more than what I picked, I would have been a corpse. We’d have to build a house and stable in a primitive area, but for us who lived through “paradise” there’s nothing that can scare us.

The Argentinians promised 15,000 visas for Italians, of which a small number arrived and revealed themselves to be lazy bums with many Communists.

The President of Argentina ordered all the Italian visas rescinded and given to Poles! They have decided to settle Tierra del Fuego with Poles who are

to build a port. That should be part of our program.

Presently there are possibilities for emigration to the USA, but you need cash: $5,000 per immigrant or $7,000 for a family. We cannot achieve this–as well the first visas will go (and rightly) to those who survived in Germany.

The postponement of our transport to England is expensive for us, as we live without any earnings (my school was liquidated). Janka is still going to her sewing course although she has received her diploma in cosmetology. She’s sewing me a fur waistcoat as I only have a shirt.

A few more words about Australia–it looks like all the passenger liners were sunk in the war. People are waiting for months with visas in their pockets. It’s easier to go to England or America–the expenditure for New Zealand would consume all our funds. We can’t stay in India, but going to England doesn’t make sense, nor does it for you to stay in France. In every case we take into consideration the five of us. Every possibility is still being written with a rake on the ocean.

Yours to the end of my life,

Janek

Jan writes to his sister-in-law that he and Janka have decided to join her and Czeslaw in England. In spite of his poor health, Jan is still able to joke. Upon arrival in March 1948, Jan will immediately be taken to an army hospital. Family reunification is now improbable, and in 1951 Janka will emigrate to Canada with her husband.

February, 1948

Polish Camp

Valivade/Kolhapur, India

Lusia Madalinska

RAF St. Dunholme Lodge

Lincoln, England

Dear Lusia!

Jan on his deathbed with Janka

And so we’re departing this sunny India for cold and miserable England. We’re only happy that finally we’ll see Czeslaw and you. I’m saying goodbye to India

without sadness–and I’ll be greeting England without joy.

As we’ve been dispossessed of our bodily fat, we’ll bring with us a bit of pork fat for ourselves and our beloved–so start licking your chops as I hear that in England they only give bacon for smelling. It’s too bad of course that the above-mentioned specialties won’t be featured on the holidays, and will be available probably only at the start of Lent (and maybe at Carnival as permitted by “Wali”). We’ll be bringing much exoticism–in fact we’re very exotic as we’re pale, washed-out and cooked by the Indian sun which can burn but doesn’t tan. I think that if the devils (or gods) take us to sunny Venezuela, then we’ll be right at home (India that is).

We send you our heartfelt greetings and wishes for the new year of 1948 during which we hope that finally fate will strike down our great friend Josef Vissarionovich [Stalin]. Amen! That would be joyous. May the devils take the greatest fiend in the history of the world!

Prepare for us a good “barrel of laughter”[British barracks] with plumbing, central heating and electrical fans (in and out). Naturally there should be a beautiful porcelain bathroom and…a similar toilet is absolutely required. Appropriate furnishings to match our Persian and Kashmir rugs–they simply must be mahogany or ebony! Other than that we don’t have any special needs; elevators aren’t necessary.

I kiss you as your still young brother-in-law,

Jan

Jan Sulkowski died on July 20, 1948, without ever returning to Poland or seeing his wife Natalia and youngest daughter Wanda. He is buried in St. Neot’s Cemetery, England, under a tombstone with a misspelled name and incorrect age.

July, 1948

5 S.C.C. Polish Hospital

Barm’s Farm, Storrington, Sussex, England

Natalia and Wanda Sulkowska

Ul. Malachowskiego 6

Bedzin, Poland

My Dearest Ones,

It was very bad with me–a few days ago the doctor confessed that at first he had considered me already as “deceased.” But somehow I dug myself out, and though there’s no talk of returning to my former health, I can get to a more-or-less normal state.

It was very bad with me–a few days ago the doctor confessed that at first he had considered me already as “deceased.” But somehow I dug myself out, and though there’s no talk of returning to my former health, I can get to a more-or-less normal state.

Every day in beautiful, not typically English weather, I go for a walk. The doctor says I’ll stay here in the hospital for a month maybe more. Meanwhile Janka and Czeslaw will somehow set themselves up, and then I’ll go to them. I’ll be a cook and maid for them, and if my strength allows me, I’ll start to work myself. My address is on the other side.

I would be very happy if you wrote to me–Wandulinka I must have a letter from you!

I kiss you with all my strength,

Your Daddy

Christopher Jacek Gladun was born in 1951 and grew up in Canada to where his family emigrated from England as displaced persons. Sadly, Chris died in Toronto in March 2003. He held a diploma in Journalism from the Niagara College and a BA in Polish Language & Literature from the University of Toronto. Chris also acted as interviewer and researcher for the documentary film “Rescued From Death in Siberia”.

This content is now maintained by the Kresy-Siberia Group, which Chris was a charter member of and which is taking his website and his research work forward.