Part Three – Exile: Persia, India, England, Canada

India

We arrived in Karachi, India, on May 16, 1943…going from the frying pan into the fire in terms of tropical climate (and monsoons) which I, and particularly my father, tolerated poorly. It would have an adverse affect on his already-poor health. In fact many Poles succumb to the diseases endemic to this climate.

We had no idea how long we would be here. Upon disembarking, we thought in terms of months–but it turned out to be almost six years. Our many hopes and schemes for family reunification were being crushed at every turn by the events of WWII; to get our loved ones out of the USSR was now impossible. The Nazi occupation of Poland and advance into the USSR had disrupted communication and travel. At the same time, the Soviet government while wanting Polish help against Germany, was preventing many Poles from joining the Polish Army or leaving the USSR.

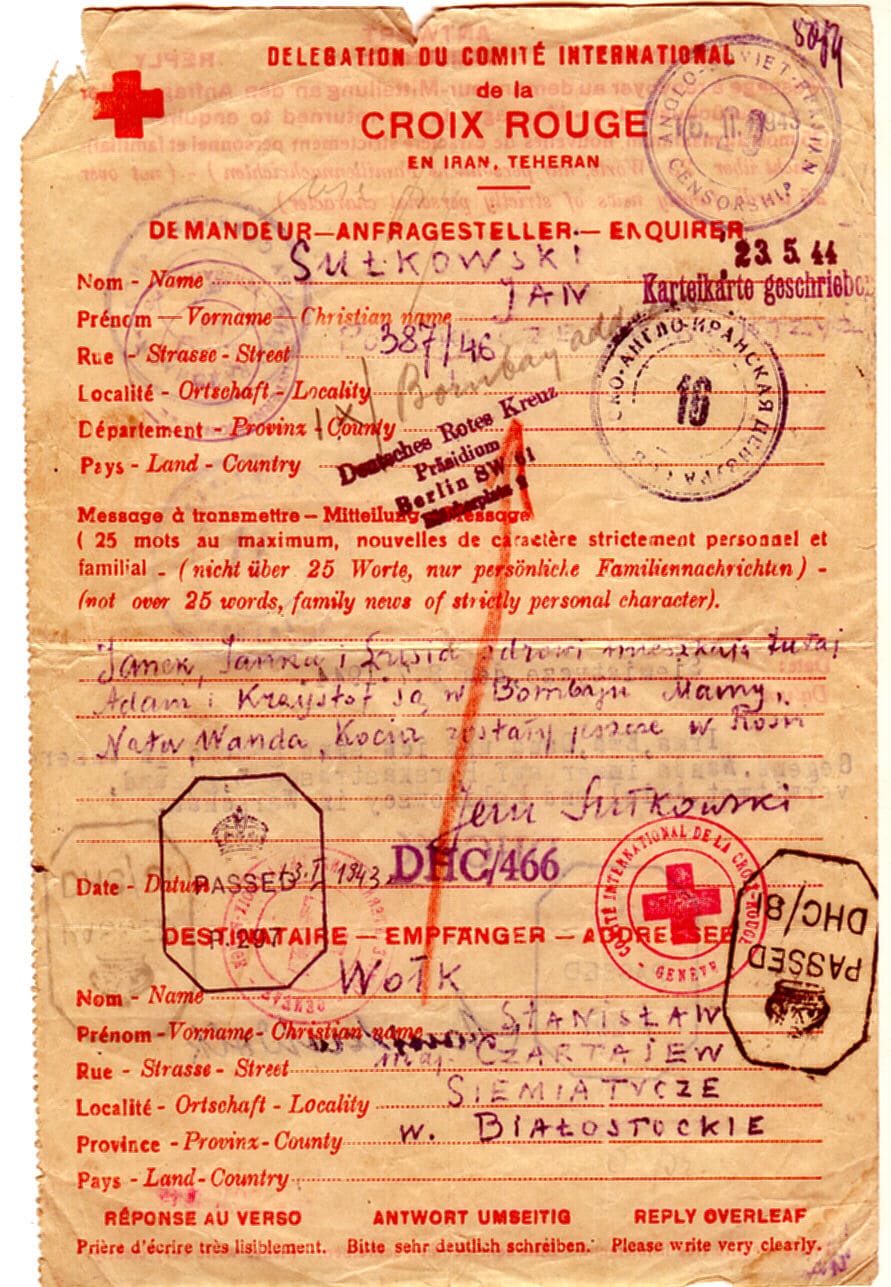

My father and I were unable to maintain our recently-established correspondence with loved ones from the middle of 1942 into 1946. Red Cross enquiries were the only tenuous source of information, such as one sent by my father from Teheran in January 1943 to his brother-in-law, Stach Wolk, in Siemiatycze in Nazi-occupied Poland: “Janek, Janna and Lusia are healthy and living here. Adas and Krzys are in Bombay. The Mothers, Nata, Wanda, Kocia are still in Russia.” The reference to Adas and Krzys was a hopeful assumption, or a ruse to throw off the Soviet censors–part of a plan to smuggle the boys out of the USSR as underage cadets via the Polish Army. But it never materialized, and the boys returned to Poland in 1946.

The message went under Anglo-Soviet censorship and was routed by the Nazis to the Berlin office of the German Red Cross. Stach’s answer, dated July 8, 1944, reads: “Irma, Ewa, Dana unde ich sind gesund in unsere Gegend. Wanda immer auf Barskastrause 5 gesund. Aniol und Malinowscy in Warschau.” Four months after sending his reply, Stach would be arrested and imprisoned by the NKVD who now controlled Poland.

The news was tragically inacurate and out of date. By the time Stach’s answer found Jan, both “Mothers” had died in exile: Stefania Urbanska in December, 1942, and Benigna Urbanska in March of 1944. Kocia perished in 1945. All three were buried in Kazakhstan by Adas, who was 11 years old when deported. Aniol (Grosicki) would be killed in the Warsaw Uprising and his wife murdered by the Nazis in Pawiak Prison in 1944.

Bombay

In June of 1943, my father, with his background in accounting, became a bookeeper with the Polish Ministry of Labour and Welfare in Bombay. It was wonderful to see my father in a suit and behind a desk once more. But he was as a sight: skeleton-thin, coughing with bronchitis–and flashing a smile of missing teeth knocked out by Soviet interrogators. At the same time I received work as a secretary-typist, and we shared the same office at 15/17 Queen’s Road, Bombay.

In Bombay we rediscovered old friends from Poland and the USSR, and made new acquaintances among the British and Indians. I would see Ghandhi–and live through his assassination and the strife that followed. I would also be courted by a real Maharajah (I visited his palace and held a pet tiger by the tail!) and by Jimmy, a brave Scottish soldier. I became a teacher and the editor of a children’s magazine called “The Little Indian Elephant” where I was known as Auntie Jasia to our Polish orphans. But our thoughts were always about family and friends. I searched as best as I could, and sometimes I was rewarded. But many times it was a death notice that came in answer to my prayers.

The “Polish City” of Valivade-Kolhapur

Sixteen hours by train from Bombay, in the village of Valivade near Kolhapur, a colony of Polish refugees existed for five years during the 1940’s. The 1946 population was 5,084, including 2,323 children, 2,248 women, and 515 adult males. Of 140 children, both parents were confirmed dead, while for 223, the mother and father were missing. Some 874 children had either a mother or a father in the army. There were 337 widows with children. Only 254 complete families existed–and disease often reduced this small number. There were other Polish camps in India, but Valivade was the largest.

My father and I arrived here in May 1947 after the liquidation of the Polish organizations in Bombay as a result of Yalta, which recognized the Soviet- imposed government in Warsaw. We were Polish survivors of Soviet genocide and could not return to a Communist Poland–but at the same the world rejected us as refugees and immigrants. Even Great Britain, for whom Poles fought and died, now washed their hands of us. We were, in a descending order of priority and respect: soldiers, veterans, refugees, wards of the British State, and finally, displaced persons or D.P.’s–with all the scorn and suspicion those letters carried, stamped into documents of rejection, and into our psyche. My father taught in the Business School and became Director of the Co-operative…and his health deteriorated. Our “Polish City” was a merry and colorful place set in the lush greenery of the jungle. There was a church with a real bell, a post office, stores of all kinds, restaurants, factories, a hospital, a sports field and even a cinema. Just like in a real town!

A School in the Jungle

There were twelve schools, made up of orphans or children with only their mothers–2,000 youngsters in all. Many of their fathers had perished in the war or were fighting somewhere. Some parents remained in German concentration camps or as slave-labourers, while others were held captive in the USSR, or shared the fate of tens of thousands of Poles, soldier and civilians, executed at Katyn and in Soviet prisons. For many children all that remained was a photo, a letter, a tattered memory, while others, after years in the Gulag, no longer could remember their father’s face or life in Poland–the Soviet authorities deliberately seperated children for indoctrination.

Instruction was in Polish and later also in English. Education was difficult for these youngsters, but many graduated to High Schools in Bombay, and later pursued higher education in England, the USA, Canada, and other countries that finally accepted them. Among these young people there were a few older men and a group released from army duties, to teach and care for them. My father and I counted ourselves among those who worked with these orphans in the Polish Refugee Camp in Valivade.

Polish children were busy from morning till night. Sporting teams, choirs, orchestras, dance troupes, religious groups, and our wonderful scouting organizations. The children enjoyed numerous activities: trips, theater and film, athletic events and camping in the nearby natural preserve of Panhalli. Youngsters put on performances for local schools and the general public, and even travelled outside to Kolhapur and Bombay. Often attending these performances was the sickly little Maharajah of Kolhapur, accompanied by his guardians and advisors. His governess claimed that the only time he ever laughed was when he attended these plays. The little Maharajah died in 1947 of some disease, but many suspected he was the victim of a power struggle and had been poisoned.

Life in Valivade

Our Polish outpost could not be separated from its physical environs: a steaming jungle with four months of monsoons and drought for the rest of the year, and sandstorms. We were near a river, which was forbidden territory. One time some swimming lads were stalked by a crocodile. A cry went up and the boys scampered to safety…but one boy remained oblivious to the drifting log (with a pair of eyes!). In a blink, the huge crocodile snatched the boy in his jaws–as his brother helplesslywatched in horror.

In some respects we lived like royalty. There were plenty of servants and help from the local population who were grateful for the economic possibilities that several thousand Poles created. In fact many Indians learned to speak (and swear!) in excellent Polish. Vendors sang of their wares in half-Polish and half-Indian, while the Indian postmaster had a command of classic Polish that put to shame many Poles. When I first arrived from Bombay, I was mobbed at the station by Hindu boys fighting over my suitcase and shouting in Polish: “Mamusia–let me take it, I’m the strongest!”

Independence for India in 1947 meant that time was running out for the Poles in Valivade. Some 500 chose to return to Poland, but 3,500 decided on England–for which the communist government revoked their citizenship. My father and I decided to sail for England and join my brother Czeslaw who had been stationed there in the RAF. On February 23, 1948, we sailed from Bombay–and another chapter was opening in my amazing life!

United Nations: Janka with friends from around the world, India, 1946.

Business Class: Teacher Jan Sulkowski (center-with flowers) and his students at Valivade-Kolhapur.

Christopher Jacek Gladun was born in 1951 and grew up in Canada to where his family emigrated from England as displaced persons. Sadly, Chris died in Toronto in March 2003. He held a diploma in Journalism from the Niagara College and a BA in Polish Language & Literature from the University of Toronto. Chris also acted as interviewer and researcher for the documentary film “Rescued From Death in Siberia”.

This content is now maintained by the Kresy-Siberia Group, which Chris was a charter member of and which is taking his website and his research work forward.