Part Three – Exile: Persia, India, England, Canada

To England

We sailed from Bombay at 19:30 hours, February 23, 1948, aboard the Asturias. With mixed emotions I watched the city slowly disappear, then the coastline–and finally all of India faded away. As did Poland, Russia, Persia. I was off for England to join my brother Czeslaw who had a job as a photographer and promised me one as well. And my father jokingly said he would be our cook and maid. At least we would have half a family.

My father had schemed for emigration to Tierra del Fuego, South Africa. New Zealand–any country willing to accept us. None would, except for England which took us on condition that we would eventually return to Poland or go somewhere else. We had mixed feelings about England, but there were Poles there, including my mother’s younger half-sister, Lusia Madalinska and her husband Zbigniew, who survived a German Stalag for four years, and held Poland’s highest award, the Virtuti Militari. Meanwhile, my mother and sister had returned to Poland in 1946–but not to Krzemieniec. They led a precarious existence trapped behind the Iron Curtain, supplanted by packages from us from India–and shortly from England.

My father kept a log of our 2 ½ week voyage, including the spot near Gibraltar where General Sikorski was killed in a plane crash caused by Soviet saboteurs or even British agents. We observed a minute’s silence in his memory.

The Promised Land…and My Father Dies

We sailed past British warships at Portsmouth and anchored just outside Southampton on March 10, but were not allowed to enter the port due for some time due to the outbreak of smallpox. Our ship flew a gold flag indicating contagious disease.

My father was taken straight from the ship to a Polish hospital. My Certificate of Identity, in which the “bearer is a Polish refugee and is proceeding to the U.K. under arrangement of H.M.G” was stamped on condition that I register with the police, do not take employment except with permission, and that I leave the country not later than specified by the Secretary of State. My vitals were: Age 33; height of 5′ 4″; brown hair and grey eyes; and no “special peculiarities, remarks or observations.” Nothing special? I thought of the last ten years and burst out laughing! My occupation was “refugee” and my profession “dressmaker/clerk.” Still it was better than India and certainly preferable to the USSR.

Quo Vadis?

World War Two had ended–but what of the countless Poles in exile? Most of us could not move back to a People’s Poland where thousands were dying at the hands of the Communist secret police. Poland had been cynically sold out by the British and Americans to the Soviets, in spite of spilling our blood in the Allied cause. We were refugees that nobody wanted, and many Poles continued to live for years in various army bases and hospitals. I did not want to spend my life in “a barrel of laughs” as the corrugated tin barracks on army bases were called.

The war finally took its toll on my father’s health and he died on July 20, 1948, at Polish Hospital No. 6, Diddington Camp. We buried him in St. Neot’s Cemetery only to discover later that his tombstone contained the wrong age (he had been 61 and not 67) and his name was misspelled. How it must have broken his heart to not see his wife and youngest daughter before he died–and theirs as well. One of the hardest things I had to face was writing a letter to Poland to inform them.

I found work as a chambermaid at the Courtland Hotel in London and began to teach myself English. Here I was struggling with conjugations when I should have been teaching them! The hotel staff were enamored of my Polish accent, and there were continuous requests for me to pronounce “sheet” which invariably came out as “sheeeiiit”–with everyone collapsing in laughter, myself included! This was among the most difficult of times for me. Family reunion was doomed and my job prospects were limited. I could not return to Poland and yet I did not feel at home here. I often travelled the London Subway and thought how easy it would be to just make a “wrong step”–and no one would miss me. But always the old fear of broken limbs and screams from a Siberian forest, made me turn back. In the English press Stalin was being hailed as a great hero while Poles were being vilified. British unions even took steps to have Poles fired, and the British never would grant pensions to Polish airmen who served in the Battle of Britain. At the Victory Parade in London all the Allied nations took part, except for one: Poland was not invited at Stalin’s request.

Friends and Lovers…

I was happy to be reunited with my brother whom I had not seen for eight years, and I found old friends, some of whom I feared were dead. Others suffered mentals problems and even chose suicide.

In London I met Jakub Hoffman whom I’d last seen in Persia setting off with Polish orphans for Africa, where he spent several years in Uganda, Kenya and Tanganyika. His wife died in Teheran and his son perished in the USSR, and he was alone now. This freedom fighter, member of the Polish Sejm, educator and writer, now operated an elevator. But he was also writing and publishing, and was active in the émigré circle of Krzemiencians, which I joined.

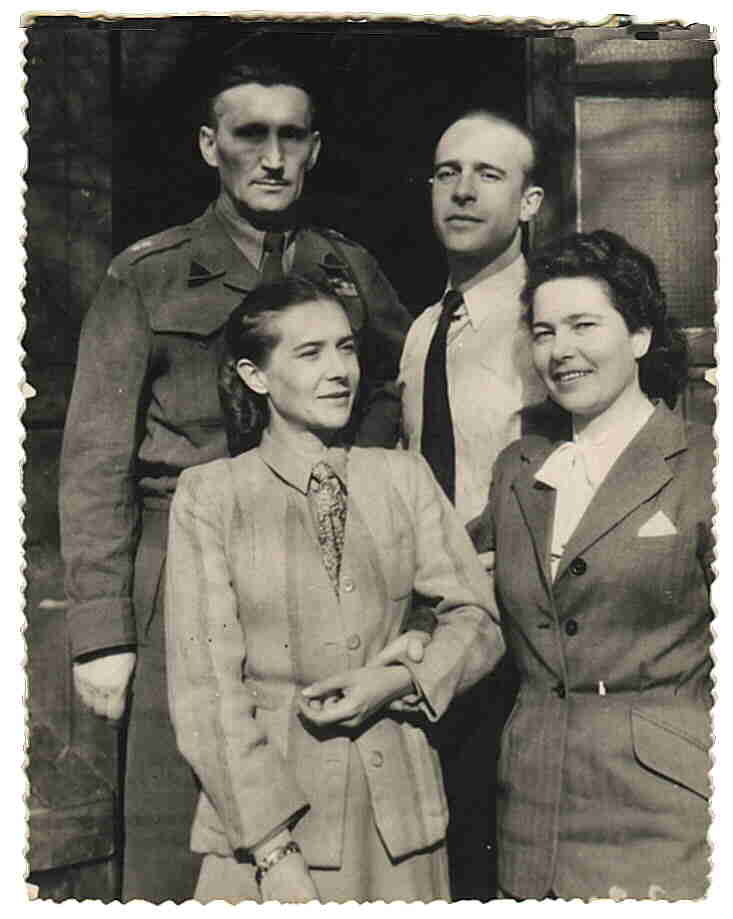

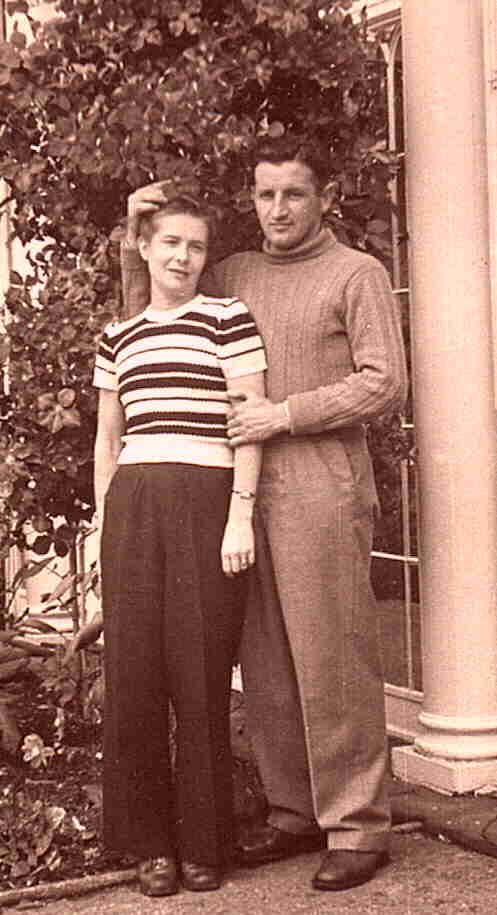

I was also visited by my old friend, Leon Gladun, a demobbed lieutenant and a hero of the Italian Campaign. He had a box full of medals–and few prospects. A friend of mine, Lilka, acted as matchmaker, and we were wed on February 19, 1949 (just as Moses had predicted, though I didn’t tell my new husband who frowned on such things!). Our marriage certificate listed us as “chamber-maid” and “railway laborer.” We honeymooned on the Isle of Wight. My brother, like so many airmen, married a wonderful English girl, and encouraged us to follow him to Canada.

We moved to the Paddington District of London and struggled at odd jobs and training courses. My son, Jacek, was born on April 17, 1951. Following his birth, I proudly made it through my first novel in English: Bram Stocker’s Dracula–which frightened me so much, I constantly checked on his crib lest the vampires had stolen him!

The Land of Maple Syrup

In November of 1951, we sailed for Canada aboard the S.S. Canberra, in my brother’s footsteps. This land of maple syrup, clean air and employment opportunities, seemed like the best place to raise a family (I was pregnant with my daughter Wanda). We disembarked in Quebec City in a winter storm, with Jacek exhibiting whooping cough–and almost set off in the wrong direction. Our destination was St. Anns, Ontario, and not St. Anns, New Brunswick…a possible error of 1,500 miles!

We settled down in St.Catharines, Ontario, near Niagara Falls, where Wanda, was born in 1952. Leon worked at a General Motors plant till his death in 1973 from complications arising from the diseases that he had fought during the war. His passion for carving, which he picked up in surviving a Soviet POW camp, filled our house and yard with his beautiful and exotic creations.

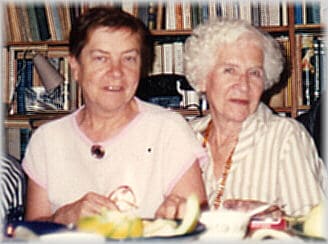

Life in Canada was wonderful and we proudly accepted Canadian citizenship. I became a Polish teacher and a children’s columnist with a Polish newspaper, as well as organizing reunions of veterans and survivors. All the while I searched for lost relatives and friends–and found a few. Eventually I sponsored my mother to live with us in Canada, and in time visited my sister Wanda in Poland. I have actually lived outside of Poland longer than in it–but how the memory of Krzemieniec lingers! And often I marvel at the prophecy of Moses, given to me a long time ago in a distant land, which all came true.

SS Canberra

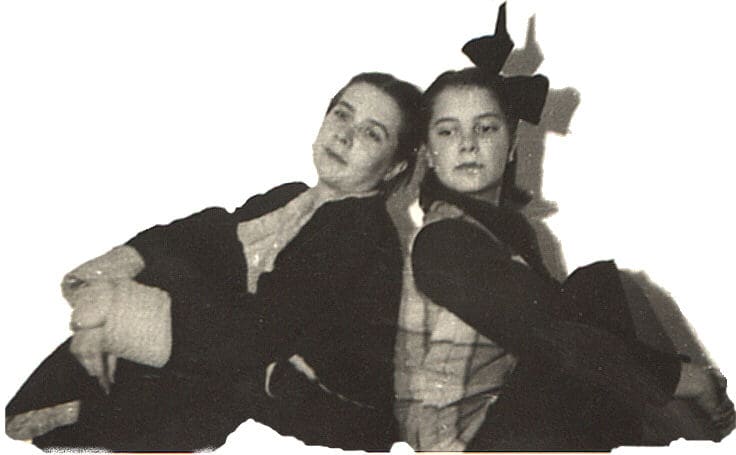

Sisters Janka and Wanda, 1936

Wanda and Janka in 1992

Christopher Jacek Gladun was born in 1951 and grew up in Canada to where his family emigrated from England as displaced persons. Sadly, Chris died in Toronto in March 2003. He held a diploma in Journalism from the Niagara College and a BA in Polish Language & Literature from the University of Toronto. Chris also acted as interviewer and researcher for the documentary film “Rescued From Death in Siberia”.

This content is now maintained by the Kresy-Siberia Group, which Chris was a charter member of and which is taking his website and his research work forward.