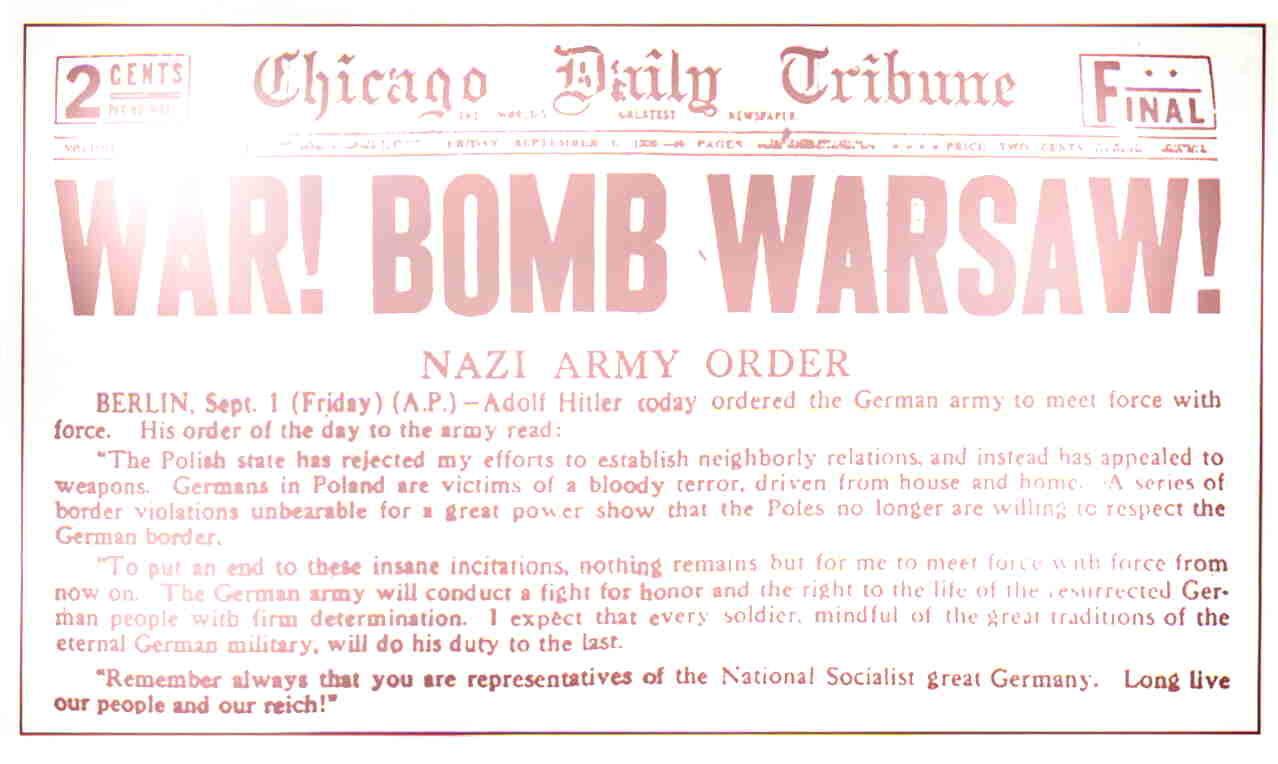

Krzemieniec Schooldays, 1939-40

Wanda Sulkowska

The Sulkowski Family: Janka, Natalia, Jan and Wanda (photo by son Czeslaw).

Budenovka: Soviet army hat

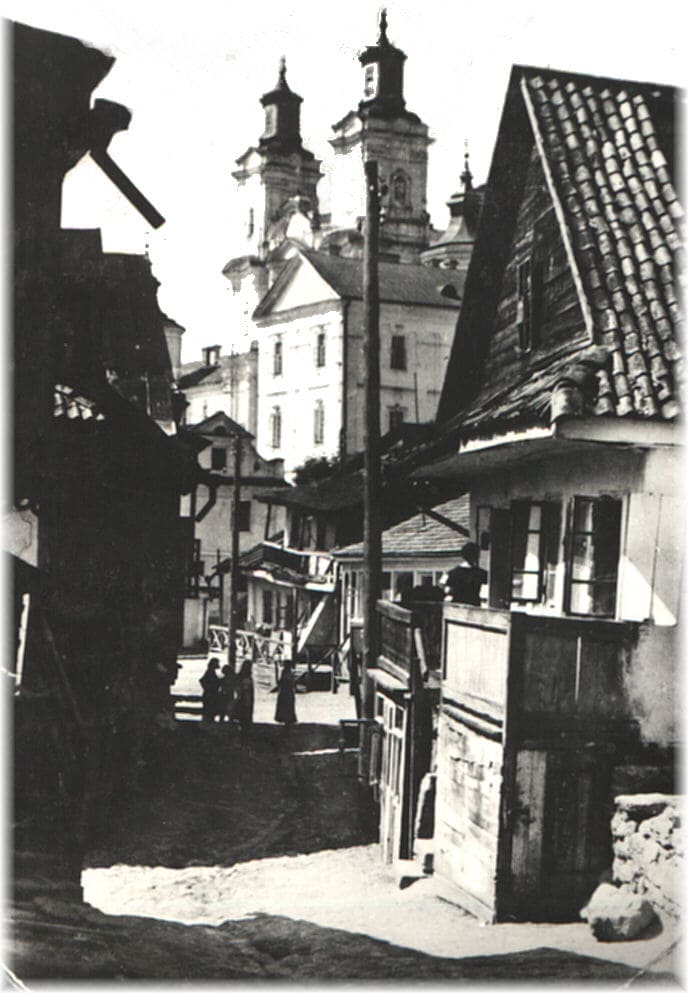

Krzemieniec High School in background.

Zbik: Wanda's beloved cat.

Natalia and Wanda in Kazakhstan

First Day of High School – First Day of War!

I just turned fourteen and couldn’t wait for my first day of High School in our town of Krzemieniec in southeastern Poland. But on September 1st all our dreams were upset by Hitler’s sudden attack. My sister Janka and brother Czeslaw canceled their university plans and rushed home. My father Jan, Secretary of Krzemieniec County, was already caught up in the terrible events along with Natalia my mother. A horrid whirlwind was about to scatter our happy family… A Gulag and Holocaust Memoir

This war was utterly incomprehensible to my young mind. How could Warsaw be bombed in the first few hours? Daddy’s huge radio added to the confusion by broadcasting military messages: “Attention… Approaching…Passed.” Next day in class we learned that during an air raid one should escape into a shelter or cellar. Then a man showed us how to make gas masks which he said would protect our lungs for ten minutes. Finally bandages were handed out with the advice to carry them at all times. Students were put into work groups and I picked fruit to make marmalade for our brave soldiers as well as stirring a huge spoon in a bubbling kettle. But I never would find out what became of that marmalade.

Refugees and Embassies

The first days of war saw refugees arriving by any means possible, from trains to bicycles to foot. Some found haven in our home while others just grabbed a bite before continuing. Janka also brought in those wounded or in shock Mama practically did not leave her kitchen while our servant girl was run off her feet. Daddy toiled 24-hours a day to accommodate embassies, government offices, and even American reporters fleeing Warsaw for Krzemieniec which was designated as temporary headquarters. Relatives described the horrific strafing by German planes of roads and trains packed with refugees. My father’s sister immediately left for the front–she was a nurse. But the children still did not comprehend that this war brought death and suffering.

Around the 9th of September embassy vehicles began to show up. A friend boasted that he identified the cars of the Swedish and Turkish embassies by a small flag on the front. This fascinated me and I got hold of an atlas with flags of the world. Clutching it, I ran with friends through the streets in search of fleeing diplomats. Spotting an embassy car, I’d consult my atlas and correctly name the country. I felt so important. A catch was the huge yellow Cadillac of the USA which in Krzemieniec was repainted for protection. One car I missed was the Japanese. My sister told me she saw them drunkenly careen into town with a big flag on the roof as if to tell the Germans: “Don’t shoot–we’re allies!” Flag-spotting was not only a game but a lesson in geography as discussions arose about the country. This was in contrast to the horse-drawn wagons loaded with wounded soldiers and civilians which bore no flags except death shrouds.

Those days were so full of happenings that it felt they were at least 48 hours long! Often I was sent on errands, such as bringing sandwiches to my father in the municipal office or conveying communiques between bureaus hastily set up in hotels and homes. Daddy told us how he’d actually held one of the bars from Poland’s gold reserves which secretly stopped here on it’s flight from the Nazis. Once walking down the corridor I glanced at the name on a valise: Józef Beck, Poland’s Foreign Minister who had stood up to Hitler! Unfortunately the Germans quickly discovered that embassies and officials had found refuge in our small but beautiful town.

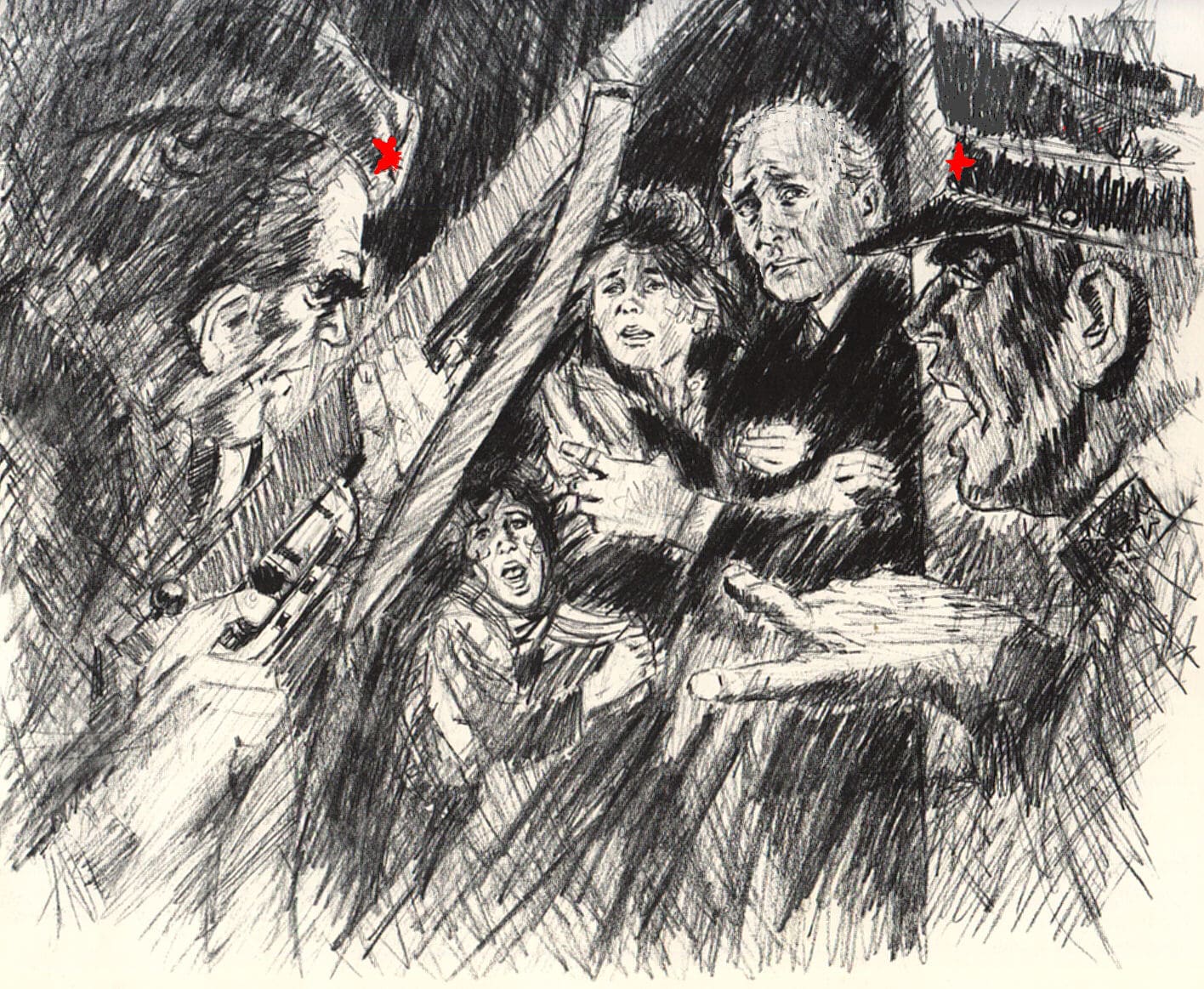

German Stuka Attack

On September 12th Stuka planes swooped out of a quiet sky and dropped their bombs on our city. I was on an errand when I heard their awful roar–and recalling my training at school, I grabbed a child and screamed: “Into the cellar!” It seems we had just gone a few steps down when it was all over. I returned to find Mama hysterical as none of us had been home during the raid which left many dead and wounded. It had been market day, full of peasants in traditional garb, Jewish merchants, artisans and buyers. Janka told me of the carnage, vegetables and human limbs in a bloody mess–and the Swedish film crew that calmly filmed the results of a Nazi attack on a defenseless town. A few days later all the embassies left for Romania, as would our government, leaving us to fend for ourselves.

After the German strike, air raid alarms began. and a hasty bomb shelter was built near our house. Everyone would frantically rush there for safety. The Swedish ambassador jumped down in a panic–and broke his leg! I also saw a Japanese official trembling so much that he couldn’t light his cigarette from my sister’s. But luckily there were no more attacks. I looked on all this with curiosity and little fear. Amazingly I felt safe with no idea of what war really was. My father decided he and my sister must stay, but the rest of the family would go to safety at an estate where we had wonderful vacations. We drove out of Krzemieniec with a long line of automobiles ahead–and I couldn’t see the end. At a crucial junction all the cars stayed on the road to Romania, while ours turned to the left. “But who is going to defend Poland?” I asked…but got no answer.

On the way we saw the curious sight of many automobiles hidden under trees. My brother spoke with a Swedish diplomat who proposed that he go with him to Sweden, but Chester refused saying that the war would be over soon and he wouldn’t abandon his family.That evening the topic among the gathered refugees was: “Why is the Polish government running away?” After all posters had declared that Poles are always armed and prepared! But we had not been expecting German steel against horses and infantry. We knew that our Polish boys were fighting well, but our lack of modern weapons was our downfall. And the British and French with whom we had treaties, were bombing the Germans–with leaflets. But what followed nobody had foreseen.

The Red Army Invades

On September 17, the Soviet Union attacked from the east while Poland was still fighting Germany. A secret agreement between Hitler and Stalin divided the country. All was lost now. I was shocked and indignant: “How could the Russians do this to us!” Daddy sent the car for us and we returned at once. Our home was still full of strangers that we had to shelter and comfort, but supplies were being bought up, and soon I would stand for hours in line just to get bread.

In the morning a nauseating smell of crude fuel and rumble of tanks announced the arrival of the invaders. The Red Army marching into town was shocking to me. A tall soldier might have a coat down to his knees while a short soldier had one dragging under his feet. Neither had leather shoes and their rifles hung on strings. Their cloth army hats, Budenovkas, , with a spike in the top amused us greatly–we joked that the spike was used by fleas for meetings! And the soldiers would madly buy up everything in the stores even as they insisted they had plenty of things in the USSR–including Greta Garbos!

Our own Polish 12th Ulan Regiment was posted nearby. On national holidays they put on wonderful parades in their fancy uniforms and fine steeds. Thus the inhabitants of our town were used to a different picture of the military. What an irony that such a ragged army now crossed our border, took our lands, and strutted around like grey geese. Even the officers didn’t look too good in their shabby coats. But the Soviets were no laughing matter. What unfolded under their occupation no one could have imagined. Many Poles were immediately executed or arrested while entire families would be deported to the USSR. Local Boy Scouts posted with old carbines were handed over by Jewish Communists to the NKVD, the Soviet equivalent of the Gestapo. We heard stories of Polish soldiers being executed after surrendering. In the countryside the Soviets encouraged ethnic minorities to attack Poles with scythes and axes–and some did!

A New School and Director

Our schools were re-opened based on Soviet models. Young people were told to attend. We had no choice so off we went. In high school Ukrainians were taught in the morning while classes for Poles only commenced at three in the afternoon. I’d gather with friends in class before the bell. Our first task was to retrieve and hang Polish pictures thrown down by Ukrainian students. We’d then recite prayers; some professors were deliberately late in order not to witness this forbidden exercise. It was difficult to learn anything. Professors changed often and pupils were transferred from one class to another. In the end all our portraits disappeared, replaced by ugly Communist heroes.

It was now late autumn and lights were turned on in class. This prompted our boys to pull pranks of turning the lights off and on rapidly. We all laughed, but few of us realized that NKVD headquarters had moved in directly across from the school. The ever-suspicious Soviets thought these flashes were signals meant for partisans who were hiding in the hills. Our boys knew nothing about partisan activity.

The NKVD began paying visits to the school director who was one of the few Poles allowed to remain. They took him for unpleasant “discussions.” He pleaded with us to stop the pranks and to not destroy the new paintings. But it was difficult to control youngsters who didn’t understand the situation. The pranks continued as did visits by NKVD officials, and their interrogations finally took their toll. The director’s heart gave out. His funeral in December was attended by all the students. It also signaled the end of our famous and beloved Krzemieniec High School which had been known as Poland’s Eton. I write about what I witnessed as a student in her first year of high school–I was 14-years-old.

After Christmas things got worse. We now attended Polish Middle School Nr. 2 in an old building. Appointed as director was a Jewish Communist named Pinchas Pinczuk who had been released from prison by the Soviets. Small, bald and with a growth on his head, he screamed at students when not trying to recruit them as spies. He was both comical and loathsome to us. But it was no joke as several students and professors would be arrested and sentenced to death.

My friend Olga and I couldn’t grasp why we had to learn Russian and Ukrainian. We found we no longer cared for schooling. Our Ukrainian teacher spoke to us solely in that language–and we didn’t offer a peep in reply. Such was our education. Olga and I would escape many lessons by hiding in the cloakroom, but this was dangerous as the hated director would search the cloakrooms in person. Somehow he never caught us. The Polish students were treated as prisoners. Doors would be locked and the janitor insisted that only the director had the key. During breaks we’d be given a cup of black coffee and a slice of stale bread, and told to be grateful. Sometimes the director would burst in and ask the teacher what students were missing; he’d scribble their names in his black book. Finally Olga and I stopped attending school and spent our time together.

Olga and her family lived in the villa of her uncle, Senator Pawlowski, but they only had two rooms and a kitchen as the rest had been requisitioned by Soviets bigwigs. I remember us sitting in her kitchen playing cards and feasting on apples which had been bought at a dear price as they were now delicacies. There were shortages of everything. In our home it was cold during that severe winter. Daddy was sick with bronchitis and his nerves badly frayed. He had been removed from his position and was forced to work in a peat mine where the Soviets needed his skills in accounting and Russian. My brother Czeslaw toiled at extracting the peat and we used in it our stove where it burned poorly and stank horribly. Most of our house had been taken over and we put our furniture into storage or gave it away. My mother soon started pawning beloved articles to make ends meet. Many of our refugee guests had to move out, but Janka still brought home soldiers or members of the Resistance whom she gave clothing and food, and fake ID’s. She also traveled to nearby cities as a courier of secret messages for the Polish underground–I once saw her cleverly hide them in a bar of soap!

One day a former teacher came to visit. Surprised that I wasn’t in school, he begged me to attend. I suspected that Pinczuk had sent him, but I promised to go. In my very first class the director began cursing and calling me an ignoramus and I was ready to burst out crying. But I surprised myself by silently wishing him a “sudden and unforeseen death!” When we got our report cards, mine had lots of “F’s” in Ukrainian, Russian and so on. I didn’t care.

Daddy is Arrested by the NKVD

Easter brought terrible events. On Good Friday an NKVD officer with two civilians burst into our home in the night. They searched for weapons and arrested my father. My generous father who helped so many people would be sentenced to hard labor for such crimes as “speaking of the low quality of Soviet goods.” His real crime was being Polish. Daddy was suffering from an ear infection and barely able to stand as they dragged him off to the jail where hundreds of our neighbors would be tortured and murdered by the Soviets, and later the Nazis. I was traumatized, but little did I suspect that I would never see Daddy again. I cried through the rest of the night and ended up with a fever.

My Sister is Arrested

On Easter Sunday I went to church to pray for him; it was also election day and soldiers were “encouraging” people to vote in a process with predetermined results. When I came home the same NKVD officer was there–and now he was after Janka. He herded everyone into one room guarded by a soldier with a rifle, while I was taken to witness the ransacking of my sister’s room. The officer put a beautiful photo of Janka into his briefcase…and then they threw apart her things searching for “evidence.” A goatskin hung above our couch in which a rustling sound was detected by one of the NKVD who began cursing and choking it when it wouldn’t yield its contents (inside was a letter to Janka from her underground leader!). Luckily the NKVD officer had to leave to get a car to transport my sister. The soldier was left to guard us.

Just then my mother and brother arrived from NKVD headquarters where they delivered food to my father, but weren’t allowed to see him. When Mama discovered what was going on, she began cursing the soldier in Russian! Janka tried to calm her down but to no avail. But then a strange thing happened. The young Russian soldier tearfully explained that he was just an ordinary recruit who didn’t want to persecute anyone and so on. Mother forgave him and served him cake while I poured tea. He wolfed it down thankfully. But what a scene when the NKVD officer returned. He screamed while the soldier saluted and begged to be sent to the front!

I was holding Janka and crying when she whispered that the soap near the oven had burst revealing it’s secret contents. Discreetly Czeslaw managed to throw the damning evidence into the stove and later fished out the letter from the goatskin. As they separated us I couldn’t imagine that it would be many years before I’d embrace Janka again.

Our Deportation

Our tragedy culminated on April 13, 1940, when two locals, a Jew and a Ukrainian, arrived bringing a Soviet soldier with them. “You have thirty minutes to pack!” they growled. Flashing in my head was the word that terrified all Poles: Siberia!

Mama and I lost our composure. But Czeslaw began packing and throwing together bundles, and he ordered us to gather things like tools and boots. Czeslaw was hampered by the soldier who followed him everywhere and wouldn’t allow him to take an axe–a weapon! My beloved cat Zbik was running after me and when I asked Mama what would happen to him she just said: “It’ll be a lot colder for us.”

Then we were ordered to hand over our house keys to someone. But who? Mama knew that the poor Jews weren’t being deported, yet, and she gave the address of her tailor. When he arrived Mama asked him to take care of our whole fortune and distribute certain valuables to remaining friends in town. I grabbed his hand and begged him to take care of Zbik, and he agreed. Later I learned that Zbik ran away and our things were stolen or sold at low prices by the NKVD–photos were thrown into a fire by those who wanted the frames.

We then loaded our thing into a peasant’s wagon waiting on the street. It was barely light as we rode down streets of dirty snow to the rail station. I beheld Krzemieniec dripping with fog as if in tears. This would be my last memory of home. A sudden thought: “My God! I was just racing down these streets with my atlas–and now where is it?” I had forgotten it. But would I need it where we were going?

I snuggled up to Mama and she to me–we felt so alone and lost.

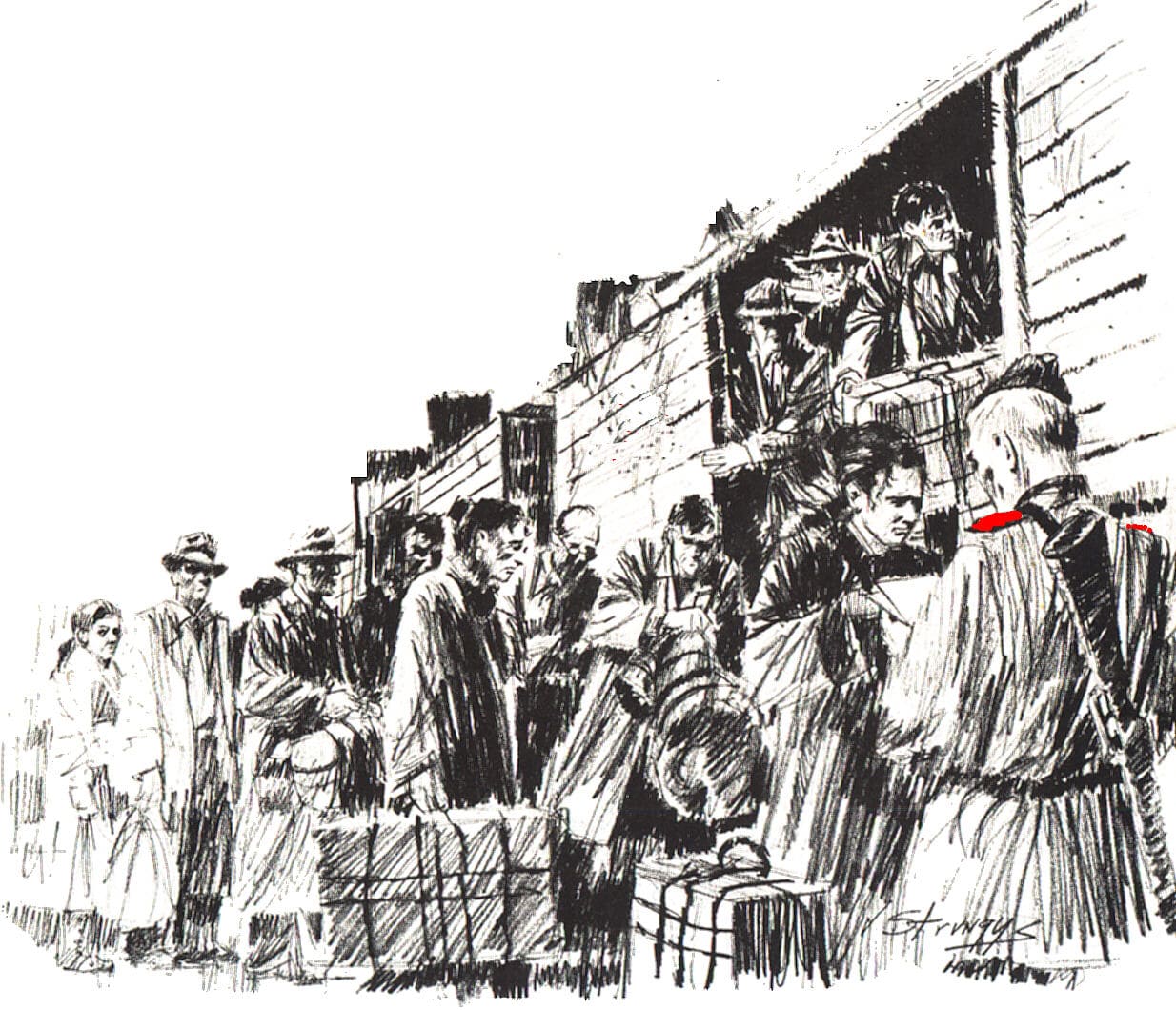

The Station of Sorrows

“Into the train!” a guard shouted in Russian. The station was full of wagons unloading their human cargo, including entire families.

“Faster, faster!” Soldiers with bayonets and guard dogs crammed sixty or more people, mostly women and children, into cattle cars. A soldier smashed a woman in the face when she tried to hand food to loved ones in the train. Cries and sobs filled the night…

We shivered on a shelf near the top of the wagon as the wagon sat sealed for two days. Czeslaw nailed up a separation for privacy in our washroom: a hole in the floor. He also managed to sneak out and get some bread–a guard caught him, but couldn’t believe that someone wanted to get into a wagon! When finally the train steamed out, hundreds of our voices arose in Polish songs. The transport picked up more victims and numbered over a hundred wagons when it left Poland. With a heavy heart I watched the strange landscape unfolding outside my grated window. “My God! Where are they taking us?”

Kazakhstan

That thought stayed with me for the whole sixteen days to Kazakhstan in Asia–a journey so brutal, especially for the children, that the convoy commandant chose suicide under a locomotive on arrival. They threw us off in a field on the steppes, and while we sat on our bundles, work brigade leaders arrived to inspect my brother–he looked strong! And so forced labor, starvation and death awaited us here in exile. But that is another story.

Our return from Kazakhstan took place on May 31, 1946. In cattle cars, but unsealed ones with Red Cross staff who took care of a sick woman who’d left Poland as a spoiled child, and was now an adult trying to understand the past six years, and wondering if she could adapt to a new world.

Our Crimes and Punishments

The Soviets sent my father to labor camps as an “enemy of the state.” My sister was tortured and almost perished in the Gulag. Later, teaching orphans in Persia and India, they dreamed of family reunification. But Daddy died in England, and lies in an army cemetery under a misspelled name while Janka went to Canada. The rest of us–grandmothers, aunts, cousins, godparents–they shipped off to the Arctic or Kazakhstan. We indeed were a dangerous family. My mother born in Russia had married a Pole while my brother was an athlete who never drank or smoked–very suspicious! But at the first chance Czeslaw did join the Polish Army and fled the USSR, to fight the Germans in the RAF. He also chose Canada to raise a family. And why did the Soviets deport cousins Adas and Krzys without their parents–just eleven and three years old! What of all the young men, family friends, who were murdered at Katyn and elsewhere. I left many relatives and friends in that “inhuman land” under little crosses that the wind and wolves scattered….

I was a young girl whom the Soviets tried to turn into an atheist. But they just succeeded in making me a “tractor girl.” We survived that godforsaken Asian climate that was perpetually freezing or sweltering. The mosquitoes and snakes didn’t eat us nor did we accept Soviet citizenship which caused us trouble, but was our salvation in the end. We returned to our beloved Poland, though the communist government could deport us again if we dared tell our story. Krzemieniec exists only in our hearts and memory.

I passed through the severe and unforgiving school of life: from shepherd to machine operator. I stole food, coal and oil just to survive, and came face to face with starvation and disease–and human cruelty. And my formal education was lost. When I returned to Poland I went back to high school and graduated in 1950. With my diploma from the school of hard knocks I immediately went to work to support myself and my mother.

Christopher Jacek Gladun was born in 1951 and grew up in Canada to where his family emigrated from England as displaced persons. Sadly, Chris died in Toronto in March 2003. He held a diploma in Journalism from the Niagara College and a BA in Polish Language & Literature from the University of Toronto. Chris also acted as interviewer and researcher for the documentary film “Rescued From Death in Siberia”.

This content is now maintained by the Kresy-Siberia Group, which Chris was a charter member of and which is taking his website and his research work forward.