Polish Refugees in New Zealand 1944-1951

Exhibitions

Displaced Persons

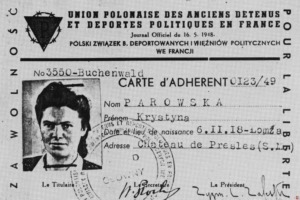

Krystyna Parowska’s French ID Card naming her as having been a prisoner or political detainee at Buchenwald Camp in Germany.

Department of Labour, New Zealand Immigration Service; The Second World War is estimated to have produced more than 70 million refugees and displaced people, the largest exodus in the history of humanity.

Even two years after the war was over, there were still 1,100,000 refugees and displaced people in Europe – victims of forced deportations, survivors of concentration camps and fugitives from advancing armies. Many of these Displaced Persons were housed in camps supervised by the Allies in Germany, Austria and Italy. They were unable or unwilling to return to their home countries, many of which were under communist rule, or had no family or home to return to.

New Zealand accepted four intakes from Europe totalling 4,852 people. They ranged from Baltic nationals, Czechoslovaks, Hungarians, Poles, Bulgarians, Greeks, Russians, Ukrainians and Yugoslavs, to stateless people displaced after the war.

The International Refugee Organisation (the forerunner of UNHCR) and several other organisations arranged the resettlement of Displaced Persons after the war.

Particular care was taken with security screening, to try to ensure that “war criminals, quislings and traitors” were not resettled.

New Zealand personnel based in London interviewed and selected “DPs”, as they were commonly known. Chartered ships arranged by the International Refugee Organisation brought them to New Zealand. They spent their first six weeks to three months in their new country at the immigration camp in Pahiatua, then renamed the Pahiatua Reception and Training Centre.

Refugee Women The New Zealand Refugee Quota Programme; p16-17;

Voices

Voices

Two Transports of Displaced Persons (DPs) arrived in New Zealand within one year of each other. Displaced referred to those Europeans who were uprooted by war, and, because of the Communist regime, were unable to return to their homeland. There were Polish people among those. All of them had been through German labour or concentration camps. DPs were different from the ex-servicemen who were brothers and fathers of the children and came to New Zealand after the war.

Essence; p151

At the age of 20, I married a Polish political refugee who survived persecution in three different German concentration camps. He later studied in Paris and came to New Zealand with Displaced Persons who arrived after the war. He decided to make his home here because he was so impressed with the equality of human relationships in this country.

Women Refugees: The New Zealand Refugee Quota Programme; p41

My five aunts – Anna, Maria, Stanisława, Stefania and Wiktoria Zazulak – were at the Polish Children’s Camp in Pahiatua. I arrived in New Zealand with my parents in 1952. Though my early experiences before arriving here were different to those of my aunts, there were similarities in growing up as an alien child in this country.

While my grandparents and my aunts were deported to Russia during World War II, my father was taken prisoner by the Germans and spent the war there. After the war, a letter from the Relief Society for Poles, dated 30 December 1946, was received by my father at the Polish Displaced Persons Camp at Westfalen, Germany. It was to advise that both of my grandparents had perished in the USSR in 1942 and that my aunts were now located in New Zealand. The letter went on to say that there was no knowledge at that time of my uncles Józef and Antoni.

However, this was the start of my parents’ dream. And so six years later, of which I remember very little, the family, consisting of my mum, dad, brother Jan, sister Janina and myself, left the small coal mining town of Vucht in the Flemish province of Limburg and via Switzerland arrived in the Italian port of Genoa. The journey by sea began in April 1952 and, after transit stops in Fremantle and Sydney, we disembarked in Wellington on 2 June 1952. We were now in New Zealand and officially registered as “aliens” under the Aliens Act 1948.

New Zealand’s First Refugees Pahiatua’s Polish Children (3rd edition); p262

When the last of them [editor’s note: “the Pahiatua Polish children”] left the camp, it was converted to accommodate “displaced persons” who migrated from forced-labour camps in Germany. They were also stateless because of the boundary changes in Europe after the war. By 1952 the last people left the camp and it was finally closed.

New Zealand’s First Refugees: Pahiatua’s Polish Children (3rd edition); p26

Although the Polish Children’s Camp at Pahiatua had remained home for the Polish refugee children for nearly five years until they gradually dispersed throughout New Zealand, the camp did not immediately close. It was unoccupied for a time until in August 1949, approximately 1,000 Displaced Persons arrived from Europe.

Under international agreements, this Dominion was one of several countries who offered to take numbers of these refugees. New Zealand personnel based in London interviewed and selected “DPs”, as they were commonly known and they were assisted by the D.P. Division of the Boy Scouts International Bureau which had been formed at the request of the Eleventh International Scout Conference in 1947. Intended as a first phase, it was an attempt to show the world what Scouting could do to assist these DPs and that the World Brotherhood of Scouts was not merely a fine sounding but empty phrase. Later phases took place in the countries of their adoption in different parts of the world.

New Zealand accepted four intakes of these Displaced Persons from Europe totalling 4,582 refugees. They arrived on chartered ships arranged by the International Refugee Organisation and spent their first six weeks to three months at the immigration camp in Pahiatua which, by now had been renamed “The Pahiatua Reception and Training Centre”.

Adventure Unlimited – 100 years of Scouting in New Zealand 1908-2005; p 136

Many of the displaced persons who came after the war had spent the war years in prisoner-of-war, labour or concentration camps in Nazi-controlled territory. They were often without identity papers. New Zealand belonged to the International Refugee Organisation that settled these people. More than 700 Poles were among the 4,500 displaced persons who arrived between 1949 and 1951.

Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, URL:http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/poles/page-2

[Editor’s note: Among the refugees who came to New Zealand after the end of the war was the Tarasiewicz family consisting of the mother, Alexandra and her two children, Maria and Alexander. The family had been evacuated to Iran with the last transport of Polish refugees from the USSR and then sent to the Polish camps in India where they lived until 1947. Like many families not wishing to return to a communist Poland they had to choose a host county.]

Uncle Lovat continued to process our applications for Immigration to Australia and New Zealand. Finally, we were granted permits to enter both countries on 29th November 1946. Mother chose New Zealand, where she had friends from Poland in the Polish camp at Pahiatua, Mr. and Mrs. Skwarko with their two children. She wanted to be close to someone she knew well from Poland.

As the new school year commenced at Panchgani at the end of February 1947, we felt more secure in the knowledge that we had a permit to enter New Zealand to begin our new life. Uncle Lovat, still resident in India, continued to correspond with UNRRA authorities regarding finance for our passages by sea to New Zealand. On 31st May 1947 we received a letter from the Commonwealth Relations Department in New Delhi acknowledging the receipt of our New Zealand entry permit and money from the United Nations Intergovernmental Committee for Refugees. Mother was then advised to obtain an identity certificate from the passport authorities in Bombay, because her pre-war Polish passport was now Invalid. That letter also Informed us that the External Affairs Department of India had authorised the Bombay Passport Issuing Authorities to supply the identity certificate on Mother’s application. We complied with that request forthwith. (p112-113)

… On 3rd October as scheduled, we sailed for New Zealand on the Wahine, which then regularly transported passengers and cargo between Australia and New Zealand. The sea was very stormy and the gale force winds meant a rough passage. Consequently we again spent much time being seasick in the confines of our tiny cabin. … Gray skies and drizzling rain shrouded Wellington as the Wahine approached the capital city early on the morning of the 7th October 1947. It took two hours to complete all the formalities with the New Zealand customs officials before we were permitted to disembark. (p121)

… Mrs. Krystyna Skwarko, our friend from Sokołka in Poland, met us with a bunch of red tulips. We were delighted to see her after eight years and appreciated her welcome and the warmth of her personality. Together, we traveled by train to the Polish Children’s Camp at Pahiatua, where the Skwarko family lived. As we traversed the Rimutaka ranges and later the plains of the Wairarapa, we admired the luscious green pasture grazed by healthy sheep and cattle. We were impressed by the landscape of our new country. Mrs. Skwarko spoke about the friendliness of New Zealanders and their great generosity towards the Polish orphans, who had arrived here In 1944. All her assurances put us at ease. We had crossed the vast expanse of oceans from India to the land of our dreams, and we now had a chance to begin a new life with our friends at the Polish Camp in Pahiatua.

The Polish Children’s Camp was located a few kilometres from the Pahiatua township. Here the Skwarko family extended a very warm welcome to us In their small home unit. The healthy appearance of the Polish orphans at the camp impressed us immensely, as did the friendliness of the staff there. The food was excellent; rich, creamy milk, butter, cheese, plentiful meat, fresh fruit and vegetables were In abundance. This was surely the ‘land of milk and honey’ we had been dreaming of! We were unaccustomed to such a rich diet. On arrival we were extremely thin, having been seasick during much of our long voyage and we really enjoyed the wholesome new diet provided at the camp. We remained with the Skwarko family for a week. This enabled us to adjust to our environment and made the transition to a new life less traumatic. (p121-123)

… We were introduced to various staff members at the camp, including Major Finney, who was then in charge of the Polish Camp. Since we spoke fluent English, it was decided to send us to New Zealand schools in Pahiatua. Alek, now 12 years old, attended the St. Joseph’s Catholic Primary School there, while I was enrolled at the Pahiatua District High School. At 16 years of age I was placed in Form 5 to become accustomed to a New Zealand school. As it was now mid-October I was not expected to sit the School Certificate Examinations scheduled for November. Indeed, the following two months were to be a period of readjustment for us both, from an English education system in India to a new New Zealand syllabus.

We travelled to Pahiatua on a school bus which picked up children from the nearby rural area. I can still recall the first comment of a New Zealand boy on the bus. He looked me up and down, then shook his head saying, ‘You’re much too thin for my liking’. Indeed, both Alek and I looked emaciated on our arrival in this country. We lacked the robust healthy appearance of the New Zealanders. It was to take us about six months to regain our strength and increase weight. (p?)

An Unforgettable Journey; p112-113, 121, 121-123, ?

After the war Mr Lewandowski* joined the Polish Army stationed in Germany.

In 1949 he was demobilised and was given a choice of returning to Poland or emigrating to another country. An old friend who managed to smuggle himself out of Communist Poland told him about persecution and imprisonment of the AK members by the new regime. To avoid this Mr Lewandowski had no choice, but to look for a new country to settle in.

At that time he received a letter from his maternal uncle, Tadeusz Dryja-Lisiecki, who from 1936 until the end of the war was a Polish consul in India. In his letter, the Consul wrote to his nephew about his involvement in bringing the Polish orphans from Persia via India to New Zealand. The consul himself boarded the General Randall troop ship in Bombay and accompanied the children on this leg of their journey. In the letter he described New Zealand as a beautiful and peaceful country. This swayed the homeless war veteran to head south to the far-off land of New Zealand. Mr Lewandowski arrived in New Zealand in 1951 and spent the first few weeks in the Displaced Person’s Camp in Pahiatua. Later he moved to Christchurch where he lived until his death in 2006.

*editor’s note- Maciej Lewandowski was captured by the Nazis in Warsaw during the Warsaw Uprising and transported to internment camps in Germany.

Polish Kiwis; p110-111

Following the war there were numerous changes in national boundaries and allegiances and this resulted in hundreds of thousands of DPs – people who had become stateless and homeless. The United Nations formed a special arm called the International Refugee Organisation (IRO) to run a large number of camps in Austria and Germany to house the DPs. New Zealand’s Prime Minister, Peter Fraser, visited Europe in 1948 and toured some of these DP camps. Since 1943 New Zealand had been trying to establish some form of policy for accepting refugees and Fraser was sufficiently taken by the situation to convince his government that New Zealand should receive an initial draft of 1,000 DP’s, providing it could select which categories were deemed desirable. (p52)

… Early in 1949 the New Zealand government sent over a three-member selection mission that interviewed nearly 3,000 IRO-nominated refugees. Persons excluded from consideration were those of consideration were those of German descent, fascists, communists, collaborators with the Axis, criminals and individuals of bad character. Only people who had already been for a comparatively long period in camps under supervision were admitted. … Before being admitted to New Zealand, the would-be settlers had to go through three examinations. (p53)

… Gopas and his family formed formed part of the one thousand and twenty-seven emigrants queuing to board the Irish Bay Lines’ MV Dundalk Bay. The 7,000 tonne vessel had a white superstructure with the hull painted in a pleasant shade of yellow with the single funnel painted to match. It appeared that half the passengers were women and children and that overall, fifty to sixty per cent were from the Baltic States. On a rough sampling basis this confirms New Zealand’s preference for immigrants from the Baltic States. The balance of refugees came from countries which included ·the Ukraine, Poland, Yogoslavia, Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Russia. (p57)

… The Dundalk Bay had been a German Army hospital ship, named ‘Nuremberg’, belonging to the fleet of the shipping company, Kraft durch Freude. The British obtained the boat as ‘war loot’ and it came into the hands of an Irish family, running the Irish Bay Lines out of Belfast. They had been engaged by the IRO to transport this group of refugees to Australia and New Zealand.

Accommodation on the boat was cramped and relatively primitive. Women and children were quartered at one end of the boat, the men at the other. At night the iron gates that segregated these living quarters were locked -married couples were not allowed to sleep together. For the refugees it appears there were only the two large dormitories at either end of the boat and they had little light or air conditioning. There were no lounges or sitting rooms or any public areas for congregating other than on the decks. This was apart from the large dining room furnished with long wooden tables and benches for seating. There were no tablecloths, but from all accounts much of the food was not worthy of tablecloths . There was no fresh fruit supplied and very early on in the trip no fresh vegetables. Maggots appeared in the porridge and rice. The milk was powdered, the meat and fruit tinned, but the bread was baked on board and in this area there were no problems. There was a canteen for those with money. Amongst other goods, soft drinks and fruit such as oranges were available but some refugees had parted with their last money before reaching Trieste. It appears the boat was very under-provisioned. There were no sittings in the dining room and sometimes there was little or no food available for those at the end of the second sitting.

Despite these hardships efforts were made to raise the morale of the refugees. Chocolates and cigarettes were periodically distributed having presumably been supplied by the Shipping Company. Also the New Zealand authorities sent over a supply of honey that was delivered to the boat ‘en route’, possibly at Port Said. Each refugee received around a half kilo gramme pot of honey that was very much appreciated and would have gone well with the bread and toast that was of a reasonable standard.

The crew required the assistance of the refugees to run the boat and a number helped in the kitchen. The canteen was run by a group of Estonians . (p58-59)

… From Melbourne the Dundalk Bay suffered further bad weather in the trans-Tasman crossing to Wellington, finally reaching the port on the afternoon of Monday 27 June. The following morning the nine hundred and thirty two DPs disembarked for their initial processing. They were retained on the wharf, x-rayed, fingerprinted and placed on a train bound for the Pahiatua Reception and Training Centre. (p63)

… Not surprisingly, when interviewed by the Press, the new arrivals were scathing of the food and cramped conditions on the boat. this was well reported and following an enquiry the New Zealand Immigration officials complained to the IRO with the result that future drafts travelled in much better conditions.

The journey was briefly broken at Palmerston North, one hundred and forty-four kilometers north of Wellington. Here the locals distributed flowers to the new immigrants as a welcoming gesture. From there, a further forty-odd kilometers eastwards and the group had reached its destination.

The grounds of the Pahiatua Reception and Training Centre were previously the setting for the horse track of the Pahiatua Racing Club. In 1940 the Defence Department took over the track to accommodate around one thousand aliens who were deemed a security risk to New Zealand.

… In November 1944 the Pahiatua Camp became the home for seven hundred and thirty-three Polish refugee children and one hundred and five adults. (p65)

… In April 1949 the last of the Polish children left the Camp and it was then readied for the first draft of DPs, being renamed the Pahiatua Reception and Training Centre. It was run by the Army with most of the accommodation being in dormitories, although families were given partitioned space within larger areas. (p65)

The main difficulty for the newcomers was their lack of knowledge of English. Apart from the one hundred and twenty children of school age, the adults were divided into three groups which were then subdivided into subclasses of manageable sizes -the Education Department engaged eighteen teachers for the six to eight week course. (p66)

… The English lessons were interspersed with films about New Zealand and the New Zealand way of life _ the currency, the main weights and measures, public institutions such as the Post Office, Traffic, Social Security, some history and local customs, and the rights and duties of every citizen. … The people of Pahiatua were most hospitable to the new immigrants and a number were invited to visit local farms. … So grateful were the new arrivals, that they put on a concert for the people of Pahiatua – they felt this was the only thing they could do to return the hospitality. Terry Dunleavy recalls: ‘They had some tremendous talent – Lili Latisheva (a Latvian mezzo-soprano prima donna) was the star performer. (p67)

… In October 1950 the second draft of DPs arrived in New Zealand on the Hellenic Prince, which had sailed from Hamburg. (p84)

Rudi Gopas – a biography: p52, 53, 57, 58-59, 63, 65, 66, 67, 84

Mieczysława Lemów was a six year old child when she, her mother and grandmother were deported to a concentration camp in Germany during the war. Although she was born in Eastern Poland, her family was not exiled to Siberia. But persecuted by the local Ukrainians and fearing for their lives, in 1942 her family together with other Poles decided to flee. Their fears were justified, because the local Ukrainians set fire to the church with the Poles shut inside. Because they lived close to the new border established between Russia and Germany, which had divided Poland between them, they chose the lesser of two evils, as they thought, and fled across the border. The Germans were prepared for the Polish refugees, because after crossing the border the Poles were immediately herded into waiting rail cars and taken straight to the concentration camp in Dachau, not far away from Munich in southern Germany. They were detained in the main camp for three months. Their food was smelly soup served in dirty dishes. They survived by nibbling at dehydrated bread which they prudently took with them before escaping from the Ukrainians.

123 sub-camps were located in the vicinity of the main camp, to which prisoners were sent from the main camp. Families were separated and its members scattered among the various camps. Mieczysława and her mother were sent to a camp in Burkhaven. The grandmother was meant to stay behind, but a Polish man warned them to try and take her with them, otherwise she would be put to death as a useless old woman, unsuitable for work. At the new place some prisoners were behind bars, Poles, Czechs, Ukrainians, Belgians, French and Italians. These were single and unmarried. People with children were not behind bars, because the Germans knew that they would not try to escape encumbered by children. Those behind bars were under the control of SS guards; the others were guarded by ordinary German soldiers who were unsuitable for active military service. Mieczysława saw how an SS guard killed a man in view of the other prisoners, after which the people with children were herded into the barracks and the windows shuttered, so that they would not see what was happening outside. The prisoners were happy when the Americans and the British bombarded the surrounding area. Her mother was forced to shovel coal into rail lorries and then to work in a factory producing washing powder. The children had no duties and idled away their time in the camp. Any teaching was strictly forbidden, even writing and reading. Mieczysława was always yearning to return to Poland. Although the camp had no school, her mother taught her in secret how to read and write Polish. All the prisoners were destined for extermination, but they were kept alive only until such time as German soldiers were to return from the war front and need the jobs the prisoners were doing. The prisoners would then be redundant. The people were in constant fear of the Germans, who humiliated the prisoners at every step. Such constant humiliation had an adverse effect on the psyche and their self respect.

Mieczysława and her mother were shunted from camp to camp. They spent the German imprisonment in six different camps.

Towards the end of the war they were living with a German family which had a house outside a town, with a garden and three sheep. Mother was employed there because she knew how to weave raw wool, which she did from the fleece of the shorn sheep. She also worked in their garden.

Polish schools were established after the liberation in 1945. Attempts were made to catch up on the lost years without schooling and in four years Mieczysława completed six years of study. She was taught German which she did not want to learn.

Her mother tried to go to the United States, but the Americans would not take people with children. Her grandmother remained in the camp, from where she was taken by her other children to live with them in America. In 1949 Mieczysława and her mother arrived in New Zealand. She was placed in a boarding school run by nuns. She then attended Sacred Heart College in Wanganui for three years.

Wiadomości Polskie – June 2014, p15-17 *

* Monthly magazine edited by the Polish Association of New Zealand Inc.

Photos

Documents

Acknowledgements

The New Zealand Museum Gallery Room “Polish Refugees in New Zealand – Deportees Forcibly Taken to Siberia, Ex-Servicemen and Displaced Persons” was created by a workgroup from Wellington, New Zealand under the umbrella of the Kresy-Siberia Foundation. The group was led by Irena Lowe (Smolnicki), and assisted by Dr.Theresa Sawicka, Wesław Wernicki, Jackie Rzepka, Adam Manterys and Mary-Anne Morgan (Baziuk).

Theresa and Wesław have provided the team with professional assistance in the field of history. Irena, Jackie, Adam and Mary-Anne are all first generation New Zealanders and descendants of family members forcibly deported from Kresy during World War II, who subsequently came to New Zealand either as children bound for Pahiatua Children’s Camp, or as ex-servicemen and women or displaced persons.

We also acknowledge all those Pahiatua children and adults, ex-servicemen and women, displaced persons and New Zealanders who have written about their own or their family’s experiences in books and journals and provided a wonderful history in text, photos and documents over many decades. The team has not set out to rewrite the history but rather to collate the existing stories in a structure so that the interested readers and the following generations can access the stories on-line and view the history as a mosaic. We are humbled by their experiences.

We are grateful to our sponsors who have enabled the publication of this gallery.

Stowarzyszenie Polskich Kombatantów SPK (Polish Ex-Servicemen’s Association)

Polish Charitable and Educational Trust New Zealand

The Morgan Foundation

Dr Zbigniew Popławski – in memory of the Popławski family

Andy and Anthony Bogacki – in memory of the Bogacki and Zielinski family

Eugenia Smolnicka – in memory of Michał and Antonina Piotuch

Jackie Rzepka – in memory of the Rzepka family

Steve Witkowski – in memory of the Witkowski family

Bibliography

Sources

Alexandrowicz, S.Monica 1998. “Z Lubcza na Antypody“. Seria: Ocalić od zapomnienia -1. Zgromadzenie Siótr Urszulanek SJK.

Beaupré-Stankiewicz, Irena, Danuta Waszczuk-Kamieniecka, and Jadwiga Lewicka-Howells. 1989. Isfahan – City of Polish Children. 3rd ed. London: Association of Former Pupils of Polish Schools, Isfahan and Lebanon.

Beaupré-Stankiewicz, Irena, Danuta Waszczuk-Kamieniecka, and Jadwiga Lewicka-Howells. 1987. Isfahan – Miasto Polskich Dzieci. 1st ed. London: Kolo Wychowanków Szkól Polskich, Isfahan i Liban.

Chibowski, Ks. Andrzej. 2012. Kapłańska Odyseja Ząbki. Original language edition. Polska: Apostolicum.

Chibowski, Dr. Andrzej. 2013. A Priest’s Odyssey. 1st English- language edition. Wellington, New Zealand: Future Publishing.

Dabrowski, Stanislaw. 2011. Seeds in the Storm. Waikanae, NZ: Maurienne House.

Ducat, Michelle, Mealing, David, Sawicka Theresa, and Petone Settlers Museum. 1992. Living in Two Worlds: The Polish Community of Wellington Wellington: Petone Settlers Museum/Te Whare Whakaaro o Pito-one

Jagiello, Józef. 2005. One Man’s Odyssey. Edition 2005. Józef Jagiello.

Department of Labour, New Zealand Immigration Service. 1994. Refugee Women: The New Zealand Refugee Quota Programme. Wellington: Department of Labour, New Zealand Immigration Service.

Lowrie Meryl. 1981 The Geneva Connection, Red Cross in New Zealand. Wellington: New Zealand Red Cross Society.

Manterys, Adam, Stefania Zawada, Stanislaw Manterys, and Józef Zawada. 2008. New Zealand’s First Refugees: Pahiatua’s Polish Children (2nd ed.). Wellington: Polish Children’s Reunion Committee.

Manterys, Adam, Stefania Zawada, Stanislaw Manterys, and Józef Zawada. 2012. New Zealand’s First Refugees: Pahiatua’s Polish Children (3rd ed.). Wellington: Polish Children’s Reunion Committee.

Manterys, Adam, Stefania Zawada, Stanislaw Manterys, and Józef Zawada. 2006. Dwie Ojczyzny: Polskie dzieci w Nowaj Zelandii Tułacze wspomnienia. Warszawa: Społeczny Zespól Wydania Książki o Polskich Dzieciach w Nowej Zelandii.

New Zealand Education Deptment. 1945. “Polish Children in New Zealand.” New Zealand School Journal, 1937-vol. 39 No 5, Part III:147-152.

Polish Women’s League. 1991. Wiązanka myśli i wspomnie / Koło Polek = A Bouquet of thoughts and reminiscences. Wellington, N.Z.: The League.

Rodgers, Owen. 2011. Adventure Unlimited – 100 years of Scouting in New Zealand 1908-2005. Wellington: Scout Association of New Zealand.

Ronayne Chris. 2002. Rudi Gopas – a biography. David Ling Publishing Limited.

Skwarko, Krystyna. 1972. Osiedlenie Młodzieży Polskiej w Nowej Zelandii w r. 1944. Londyn, Poets’ and Painters’ Press.

Skwarko, Krystyna. 1974. The Invited. Wellington: Millwood Press.

Spławska, Władysława Seweryn. 1993. Harcerki w Zwiądzku Harcerstwa Polskiego: Poczatki i Osiągnięcia w Kraju oraz 1939-1949 poza Krajem. Głowna Kwatera Harcerek ZHP poza Krajem.

Suchanski, Alina. 2006. Polish Kiwis: Pictures from an Exhibition. Christchurch: Alina Suchanski.

Suchanski, Alina. 2012. Alone : an inspiring story of survival and determination. Te Anau, N.Z.: A. Suchanski.

van der Linden, Maria. 1994. An Unforgettable Journey. Second Revised ed. Palmerston North: Dunmore Press.

Tomaszyk, Krystine. 2004. Essence. Palmerston North: Dunmore Press.

Tomaszyk, Krystyna. 2009a. Droga i Pamięć: Przez Syberie na Antypody. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Trio.

Zdziech, Dariusz. 2007. Pahiatua – “Mała Polska” małych Polaków. “Societas Vistulana” .

Other Books

Beck, Jennifer, and Lindy Fisher. 2007. Stefania’s Dancing Slippers. Auckland: Scholastic New Zealand. [Children’s Book]

Domanski, Witold (Vic). 2011. A New Tomorrow: A story of a Polish-Kiwi family. Masterton, NZ: Tararua Publishing.

Jaworowska, Mirosława. 2011. Golgota i Wybawienie: Dzieci Pahiatua od Syberii do Nowej Zelandii – Cztery Pory Roku jak Cztery Pory Życia Warszawa: Studio Jeden.

Kałuski, Marian. 2006. Polacy w Nowej Zelandii. Toruń, Poland: Oficyna Wydawnicza Kucharski.

Lochore, R. A. 1951. From Europe to New Zealand: An Account of our Continental European Settlers. Wellington: A. H. & A. W. Reed in conjunction with the New Zealand Institute of International Affairs.

Lubelski, Katolicki Uniwersytet. 2007. Z Sybiru na drugą półkulę : wojenne losy Polskich dzieci z Pahiatua. Lublin: Wydawn. KUL.

Pobóg-Jaworowski, J. W. 1990. History of the Polish settlers in New Zealand, 1776-1987. Warsaw: CHZ Ars Polona.

Ogonowska-Coates, Halina. 2008. Krystyna’s Story: A Polish refugees journey. Dunedin: Longacre Press.

Roy-Wojciechowski, John, and Allan Parker. 2004. A Strange Outcome: The Remarkable Survival Story of a Polish Child. Auckland: Penguin Books.

Szymanik, Melinda. 2013. One Winter’s Day in 1939. Auckland: Scholastic. [Children’s Book]

Turol, Sophia. 2010. Sophia’s Challenging Journey: Self-published.

Wiśniewska-Brow, Helena. Give Us This Day. Victoria University Press.

Other Materials

CraftInc. Films. 2015. Polish Children of Pahiatua. 70th Reunion – HD. Wellington: CraftInc Films. Produced by Wanda Lepionka and David Strong. [Film].

Gillis, Willie Mae. 1954. The Poles in Wellington, New Zealand. Edited by Department of Psychology. Vol. No. 5 Publications in Psychology. Wellington: Victoria University College. [Research]

Krystman-Ostrowski, Teresa Marja. 1975. The Socio-Political Characteristics of Polish Immigrants in Two New Zealand Communities, Department of Politics, University of Waikato, Hamilton. [Thesis]

National Film Unit. 1944. Weekly Review 169. Wellington: National Film Unit.

O’Brien, Kathleen. 1966. The Story of Seven-Hundred Polish Children. Wellington: New Zealand National Film Unit. [Film]

Ogonowska-Coates, John Anderson in collaboration with Halina. 1996. Exiles: The Story of a Polish Journey. Wellington: Ace of Hearts Production in Association with Polish Television. [Film]

Sawicka-Brockie, Theresa. 1987. Forsaken Journeys, Department of Anthropology, Auckland University, Auckland. [PhD Thesis]

Stowarzyszenie Polaków w Christchurch. 2004. Poles Apart: Historia 733 Polskich Sierot. Christchurch: Canterbury Telivision (CTV). [Film]

Tomaszyk, Krystyna. 2009b. The Story of the Polish Children in Isfahan – Iran 1942-1944. [DVD]

Indexes Of Names

Dundalk Bay – Ship carrying Displaced Persons to New Zealand

Goya Voyage 2 – Ship carrying Displaced Persons to New Zealand

Goya Voyage 3 – Ship carrying Displaced Persons to New Zealand

Orphanage – Pahiatua – New Zealand

S.S. “RANGITIKI” – Ship carrying ex-servicemen related to Pahiatua orphans to New Zealand

SS Hellenic Prince – Ship carrying Displaced Persons to New Zealand

Contact

Kresy-Siberia (New Zealand)

PO Box 853 Wellington 6140 New Zealand

e-mail: NZ@Kresy-Siberia.org