Polish Refugees in New Zealand 1944-1951

Exhibitions

Journey from Isfahan to New Zealand

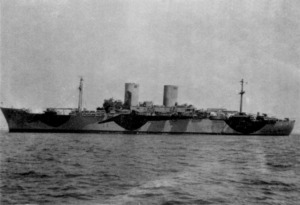

The transport ship – USS General Randall – transported the Polish children from Mumbai, India to Wellington, New Zealand together with New Zealand and Australian soldiers returning home

Dioniza Choros (Gradzik); The group departed from Isfahan, Iran, on 27 September 1944. We were gathered in a huge hall where we were given our travel instructions on how to behave as worthy representatives of our country. (p37)

… The younger children with their guardians were settled into buses and the older ones into army trucks, bunched together on hard benches. After a cold and dusty trip over the desert, we arrived in Sultanabad (now Arak) the next day in an American army base camp. The hot showers were most welcome. We visited the camp, saw short American films, and the soldiers handed out sweets and nibbles. One soldier knew no language barrier and managed to entertain us until we rolled with laughter. To them, we were their children back home and to us it was a memorable experience.

In the evening we were farewelled with speeches we did not understand but we applauded vigorously the learned speech by one of our girls. We boarded specially adapted wagons to carry the children, with benches on one side and sleeping platforms on the other. For the little children, the platforms were covered with netting to stop them from falling off. We older ones had the duty to settle in the little ones before going to bed.

The train shook and rattled on bends. We counted more than 150 tunnels on the way and the acrid smoke from the locomotives permeated everything and made breathing difficult. The children’s stomachs began to revolt against the unaccustomed overeating of sweets at the American camp and many of the little ones were ill in the carriages. We arrived in Ahwaz (which in Iranian means hell), where temperatures reach over 50ºC. We were taken to a transit camp which formerly housed the Iranian cavalry’s stables. We placed our possessions in the mangers and slept on benches. We spent our time writing letters, which were never posted. Religious services were held outdoors early in the morning to avoid the heat of the day.

After six days, on 4 October 1944, we departed by train for the port of Khorramshahr at the estuary of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, where I saw palm trees. This was the embarkation point for the refugees travelling to India, East Africa and other countries.

Our group boarded the cargo steamship Sontay. In disciplined ranks, we went below to a huge, smelly and dark cargo hold with scurrying rats. The only furniture was piles of smelly mattresses. I was horrified. Having been ill with malaria and the resultant anaemia with fainting spells, how would I survive here? We discovered that the hold would be our bedroom, dining room and living room. Food was brought from the kitchen in buckets. Parts of the floor were flooded with murky bilge water. Sleeping was unbearable in these conditions, so we lugged our mattresses onto the deck and slept under the stars, feeling sorry for the little ones who were not allowed on deck at night. Our male teachers, Mr Kotlicki and Mr Olechnowicz, tried to answer all our numerous questions. (p37-38)

… The ship had several British officers and a Portuguese crew. (p38)

… We sailed down the Persian Gulf. One day, a severe storm broke and everyone was ill. There was nothing with which to clean up the mess. The children, used to a hard life, did not complain but lay pale and ill on the deck. Our guardians were also feeding the fishes. We cleaned up later. The worst part of the journey was the terrible heat and unsanitary conditions with nowhere to wash our filthy clothes.

One day, we became afraid when an escort of two ships suddenly appeared at our sides and a small plane accompanied them. Some of the crew ran to secure the portholes. This lasted a few hours and then the escort left us. After six days, our priest Father Michał Wilniewczyc said a thanksgiving Mass on the deck for our deliverance to date. That same day, on 10 October 1944, we sailed into Bombay Harbour. (p38-39)

… After four days, our ship berthed close to the navy troopship the USS General Randall, which had a capacity to carry 7,000 people. It now carried 3,000 American soldiers and a group of New Zealand soldiers on their way home from war. We were glad to hear this was now “our ship”. Hugging our suitcases to our chests, we followed a crew member up the steep gangway to our new temporary home. The crewman Chester Wisniewski was our guide and translator. He was of Polish descent and had a good understanding of our language. His assistant was Joseph Dutkowski. We were ushered into a large hall with tiered hammock beds. The boys and younger children occupied similar halls.

There were two meals a day – breakfast and a 4pm meal. We lined up, took trays from a stack and were served by a line of cooks, each one ladling out a tonne of different food which even a wrestler could not handle, let alone children. (p40)

… The girls wallowed in the plenty of the ship’s hot water, washing their grimy clothes and enjoying the bliss of unrestricted showers. This was the best medecine for our rashes and skin ailments, which were caused by a week of exposure to salt water on the previous ship.

At 9.30am on 15 October 1944, I awoke to the ship’s vibrations. The motors fired and we were on our way on a long and dangerous journey down the Indian Ocean. (p40)

… The New Zealand soldiers, hearing that we were travelling to their country, also took us under their wing, played games on the deck with the boys and taught them English. One brave guy even taught the older girls to sing his national anthem, which they later sang at the station in Palmerston North to the surprise of welcoming New Zealanders. (p40-41)

… Each soldier was to look after one child, which made us feel safer. The ship was heavily armed, with anti-aircraft guns and torpedoes on deck. Some were covered and guarded. One day a plane appeared towing what looked like balloons and without warning deafening gunfire erupted from our ship’s guns. We were terrified.

This was war time and our ship was zigzagging across the Indian Ocean to avoid torpedoes. Until we reached Melbourne in Australia, our ship sailed in convoy with a sister troopship identical to ours carrying Australian soldiers. Each day began with an exchange of signals between the ships. For safety, the ships were made invisible at night by extinguishing all outside lights and covering portholes. One night we awoke terrified to a big jolt, the breaking of crockery in the kitchens, the scurrying of the crew and much speculation. Later, in Wellington, Captain Van Poulsen revealed that a torpedo had grazed the ship’s side, though we had already heard the rumour the next day. (p41)

… The weather cooled as we sailed south. The regular announcements to reset our watches for the time difference were wasted on us because we had none. (p41)

Our sister troopship with the Australian soldiers berthed in Melbourne and we sailed to New Zealand alone without convoy. (p41)

New Zealand’s First Refugees: Pahiatua’s Polish Children (3rd edition); p37-41

Voices

Voices

All the children from Home Seven are to be joined by their older and younger brothers and sisters who are in other Homes.

… The staff – the administration team, teachers, carers, medical and domestic staff – have to decide if they will come with us. Often, this is a very hard decision. The husbands of some of the staff are still in the Polish Army. Going to New Zealand will mean being even further away from them. One hundred Polish staff are to accompany the children, including one Polish priest, a lady dentist and a lady doctor. (p89)

… 27 September 1944. The day of our departure. Before leaving Home Seven, we gather on hospitable Iranian soil for the last time. We pray. Mama reminds us that going to New Zealand is only another step towards returning to Poland. (p89)

… 733 children and 100 personnel are loaded onto lorries to travel yet again across the desert countryside. We pass sand-covered plains, bare, rocky mountains and small patches of greenery spotted with the black tents of nomads. In Ahvaz the Polish Legation gives us visas for entering New Zealand. A British Merchant ship is to transport us from Khorranshahr to Bombay.

The only view of Bombay we get is from the height of the deck.

I was looking forward to seeing the open ocean but the water below the ship is crowded. Tiny boats, loaded with sweets, fruit and toys, are all jammed together. Dark skinned boys and men laugh and call out words we don’t understand. Beyond the boats is the shore with streets full of brightly clothed people and noisy traffic. There are also mosques, minarets and cupolas but these are red, not the familiar-to-me Isfahan-blue. House rooftops blend with the shimmering, glistening haze of the setting sun. Above the sky is blue, a dark blue now because of the approaching night. (p89-90)

… I hold onto my suitcase with one hand and to the handrail with the other. My feet feel shaky walking up the gangplank. There are many children in front of me and many behind. The water is dark and swirling. The gangplank sways. I try not to look down for too long because it makes me feel dizzy. On board, I stop for a minute and look around me. New Zealand soldiers are running up and down the gangplank easily and quickly. Some are carrying the youngest of the children on board, others are carrying our luggage.

Our bedrooms are large hall-like areas. Our beds are canvas bunks. The bathrooms are equipped with many showers, hand basins and toilets. Although there is only salt water for washing, it is both hot and cold. We eat in a large dining room and the meals are served on metal trays with separate compartments for each type of food. It is war time and there are Japanese submarines in the Indian Ocean. For safety, two American frigates will accompany us all the way. Our crew practice air raid and emergency drills to ensure our safety. (p90)

… I hear my friends laughing. The soldiers swing the rope. Girls jump over and under. The rope is thick and heavy. It is rough to the touch. It whistles when it’s up. It thumps when it’s down. We like the Kiwi soldiers. They play with us and laugh. (p91)

… Sometimes when the guns explode we are told that it’s only practice. But these sirens wail just like they did when we were in the cattle wagons on our way to Siberia. We all have to practice hiding under the deck.”

As we travel south, more days become grey days and the waves the clouds become grey.

The nights are very long and often it is hot. Hatches must be closed in case of a submarine attack. (p91)

Essence; p88, 89, 89-90, 90, 91

The journey by sea was very exhausting. On board the Sontay to Bombay, we were accommodated in holds with piles of mattresses and no bunks.

But it was too hot down in the hold, so we dragged our mattresses to the decks at night and slept under the stars. In the morning the sailors woke us up by swishing water across us and shouting: “Washing deck! Washing deck!” I did not know then what the words meant. For breakfast that morning we had Persian flat bread and salty cheese, which made us very thirsty. Later, we lined up in front of a large container with water which tasted oily, but we encouraged one another to hurry up and drink it.

New Zealand First Refugees; Pahiatua’s Polish Children (3rdedition); p69

We travelled by train to the Persian Gulf and boarded the British cargo ship Sontay. I was responsible for keeping the children fed and clean.

I don’t remember what sanitary facilities we had on the ship but I do remember that I had to bring a bucket of water down to the ship’s hold to give the children a wash at night. I was so busy that I did not have time to find out if my three younger sisters Józefa, Władysława and Franciszka were on the boat with me.

We disembarked at Bombay, India, and boarded the troopship USS General Randall. We now travelled in comparative comfort and the meals were served in a dining room. My load of washing increased because the children only had one change of clothes with them, the rest being stored in the luggage, so the washing had to be done instantly. To keep on top of my work, I began staying behind when the children were taken to the dining room and kept hunger at bay by eating chocolate.

It was a long journey and the children got used to their surroundings. The more energetic ones would run away up the steps onto the deck and Mrs Lewandowska would spend hours looking for them.

At night, I was asked to sleep next to Zofia Matula, who suffered from pain in her chest and back. She cried and groaned during the night. To this day I can’t understand why nothing was done to help her. When the ship tilted to one side (I believe it was a tactic to avoid the mines), the children would panic and start crying. It was not easy to calm them down.

New Zealand First Refugees; Pahiatua’s Polish Children (3rd edition); p201-202

On 5 October 1944 we sailed into the Persian Gulf and then into the Arabian Sea. Another week later we reached the Indian port of Bombay.

Because this was wartime we weren’t allowed to leave the ship. From there we were transferred to a US troopship the General Randall, which was already carrying New Zealand soldiers home on leave. They made us feel welcome, looked after the children like their own and showered them with sweets. They had fought alongside our own Polish troops in all the theatres of the war in Europe and Africa, and they extended their friendship to us.

The accommodation on the General Randall was luxurious compared to the earlier ship. Everyone had a hammock-type bunk and there were hot showers, mess halls and plenty to eat. We continued down the Arabian Sea and sailed into the Indian Ocean. The heat became even more unbearable as we reached the equator on 24 October. But this began to change as we sailed south. We were escorted part of the way by a convoy of smaller armed ships protecting us from Japanese submarines which fired torpedoes at us. There was gunfire from our ship’s heavy artillery and much fear. The soldiers on board said that the ship was saved by the children’s prayers.

New Zealand First Refugees; Pahiatua’s Polish Children (3rd edition); p57-58

On the way to New Zealand, I looked after the little ones, six to eight years old. They were always inquisitive and interested in everything that went on.

A Bouquet of Thoughts and Reminiscences; p26

In October 1944, a group consisting of 734 Polish children accompanied by two Ursuline nuns (Sister Monika Alexandrowicz and Sister Imelda Tobolska), Polish chaplain M Wilniewczyc and a hundred civilian personnel of teachers and guardians left Iran on the American Troop carrier “General George Randall” for distant New Zealand. The sea voyage was hazardous due to the presence of enemy submarines in the Indian ocean.

Bouquet of Thoughts and Reminiscences; p56

Then on September 27, 1944, those staying behind waved us farewell as we left for Ahvaz.

We arrived in Ahvaz on September 29, and the Polish Legation there supplied us with visas for entry to New Zealand. We were joined by several people from Teheran. They were the Deputy Delegate, Mr F. Bala, a typist, Mrs Szymanska, and Mr J. Holona, who was appointed the head of the boys’ school for the duration of the voyage.

The appointment of Mr Holona was a wise move because the care of several hundred boys on a ship certainly required a man’s hand.

We went to Basra and it was from there that we left on a British merchant ship for Bombay. We were leaving the hospitable land of Persia behind and at the same time were going further and further away from our homeland. (p49)

… When we left Basra we were all quite used to hardship but we found the journey quite exhausting. We were accommodated in what appeared to be empty holds with no bunks or hammocks. Each hold had piles of mattresses and the children would drag them up on deck each night because it was too stuffy to sleep below.

One of the first English sentences that we learnt on that boat was: “Six o’clock! Washing deck! Washing deck!” Nobody quite understood the words but their meaning was certainly made clear by the sudden appearance of a sailor with a bucket and a mop in his hands. Anyone a little tardy in removing himself and his mattress was likely to be woken up with a splash.

The children’s main pastime on the voyage was to sit and watch the ship’s gunners practising.

We reached Bombay about a week later and boarded an American troopship, the General Randall. It was carrying about three thousand soldiers on their way back from the battlefront to have leave in Australia and New Zealand.

The General Randall was almost a luxury vessel in comparison with the merchant ship. There were canvas bunks, plenty of wash basins and showers, plenty of excellent food and above all the kindness of the soldiers to the children.

They carried all the luggage onto the ship at Bombay and unloaded it again in New Zealand. During the hot days they gave their ration of fruit drinks to the children. This was a real sacrifice in the tropical heat.

They tried to break the monotony of the journey by entertaining the children with films and playing sports and games with them. It was a pleasure to see soldiers hardened by the experience of war turning skipping ropes for little girls.

Few will forget “Uncle New Zealand” and many others whose names the children did not know but whose kindness they remember to this day.

As the weeks went by, in spite of all the kindness, both the children and adults became more and more tired and apathetic. Frequent alarms, either for practice or because of real danger, forced us to stay below the decks where the air was hot and stuffy.

The enormous halls where we slept accommodated a few hundred persons each. The lack of fresh water for bathing caused sores on some people’s skins. Many were worn out by seasickness and there were recurring attacks of malaria. It was difficult not to complain.

Most of the children were not aware of the danger the journey presented but the ship’s master, Captain Von Paulsen, spent many a sleepless night worrying about the safety of those entrusted to him. It was because of the ever-present danger of Japanese mines and the likelihood of encounters with Japanese submarines that the ship was escorted for a long time by two small warships. As an additional safety measure the ship navigated a zig-zag course. (p50-51)

The Invited; p49, 50-51

We travelled in buses to Sultanabad (present Arak). I remembered that place because it was there that after having lived such a long time just as a name on a list, I was suddenly singled out.

I am sure it was all because of the red sweater I received before I left Isfahan. American soldiers were billeted in Sultanabad and one of them took me to camp, to lunch in the mess. I suffered a little during that lunch, because in our schools it was obligatory to finish up everything on your plate, and the soldiers piled up my dish with food I was not accustomed to. Luckily someone took pity on me and took away my plate. I was given sweets, chewing gum and biscuits, but I hadn’t a single pocket, and my hands were still small, so I clutched all these things in my warm hands with sticky results!

From Sultanabad we went to Ahvaz and from there to the port, where they put on a British Merchant ship. We went down below where it was dark and stuffy, and where the only furnishings were a pile of heavy sports mattresses in a boxing ring. We dragged the mattresses up on deck because it was impossible to sleep in the oppressive atmosphere below decks. In the morning, about six, a sailor came out shouting “Six o’clock, washing deck!”. No one of course understood the words, but we soon realised that we had to disappear when he started hosing down the deck! For entertainment we gazed with interest at the British crew using the anti-aircraft guns.

In this way we arrived in Bombay, where an enormous American troop carrier “General Randall” was waiting for us. It was taking home American, Australian and New Zealand soldiers. The accommodation on the “General Randall” was luxurious in comparison with the previous ship. Everyone had a bunk, even if they were in tiers, and without mattresses, there were hand-basins and showers with sea-water, but warm! We had separate dining-rooms and sufficient food and frequent visits from the soldiers and sailors, who tried to talk to us, if only in sign language; they gave us their chocolate, which — strangely! — soon sickened us, for we often fell prey to sea sickness; this was worse when, because of danger of the japanese, we were not able to go on deck. The cunning ones collected the chocolate from others, hid it like squirrels, and later traded it in the camp at Pahiatua!

Isfahan City of Polish Children; p133-134

At last the day had come. The children were told to pack – not that there was much to pack.

On 27 September they were loaded onto trucks and left Isfahan. Tony was put in a truck with twenty others. Each child received some provisions for the journey.

The convoy of trucks travelled all day on bumpy roads through the sunburnt Persian countryside. That night they stopped at some building where they were given a cup of tea and rested for the night. In the morning they set off again, heading for Ahwaz. When they passed through one small settlement, a group of dark-faced urchins chased the trucks begging for food. Tony and his friends threw them some hard -boiled eggs and bits of bread from their provisions.

It was getting dark when they reached the ancient city of Ahwaz. The trucks carried them to the train station where a long goods train awaited them. The children and their caretakers piled into the wagons through large sliding doors where they sat on the floor, exhausted after their long trip through the hot country.

The train started moving. A refreshing breeze blew into the wagon through the door, which had been left wide open. Tony sat on the edge with his feet dangling outside. He looked up at the sky and saw a full moon, and three little lights – a patrol plane circling above the train.

The next day they reached Basra, a large river port built by the British during World War l. Here, on 30 September 1944, a group of 733 Polish children and about 100 adults boarded the British merchant ship Sontay and set off for Bombay. Most of the adults accompanying the children were women. They were teachers, supervisors, cooks, administrative staff, a doctor, a dentist and two Ursuline nuns. The few men amongst them – a priest, a treasurer and the principal of a boys’ school – had been exempted from army service because of their health or age.

At 466 foot, Sontay looked huge with its four masts and a stout funnel expelling clouds of black smoke. However it was old and poorly adapted to carrying hundreds of passengers, let alone children. Having no shower or bathroom facilities did nothing to help the travelers endure the oppressive sticky heat. The ship was run by British officers, but most of the crew was Indian.

It took several hours to load the cargo and people on board. The passengers were allocated various nooks and crannies on the cavernous vessel. The largest space was the dining room also used as sleeping quarters, with mattresses piled up in the middle in an area cordoned off like a boxing ring. Rows of tables lined the walls around the room’s perimeter.

After a long wait two tugboats began to slowly manoeuvre Sontay out of the port. Little boats came near the ship and people, perhaps family members of the crew, threw parcels with provisions up on the deck.

During the week-long trip to Bombay the children spent their time sitting and watching the crew at work. Some boys had fishing rods and passed their time catching fish. The most plentiful and easiest to catch were puffer fish, which exploded if left out of water for too long.

The days were unbearably hot and humid. Thirst was best quenched by drinking lots of strong black tea that was served twice a day at mealtimes. At night the children dragged their mattresses up on to the deck, unable to sleep in the stuffy interiors below.

It was a perilous voyage through mine-infested waters. Father Wilniewczyc, the Polish priest, talked to the children about the impending dangers and encouraged them to participate in confession and take Holy Communion. In the evening, under supervision of the two Ursuline nuns, Sister Aleksandrowicz and Sister Tobolska, there were group prayers and rosaries for a safe trip to India.

Seven days after embarking they arrived in the busy port of Bombay where boats of various shapes and sizes were coming and going. Sontay stayed anchored for two days. At the end of the second day, two tugboats led the ship into the port. Under the cover of darkness the children were marched quietly down one gangway and up another.

They boarded an American troopship, USS General G.M. Randall. If Sontay seemed big to the children, then General Randall was huge. It was 622 feet long and could carry nearly 6000 people. Launched for the first time in June 1944, only four months before the Polish contingent climbed on its deck, it was almost brand new – clean, spacious and modern. On board, apart from the American crew, the Polish children and the accompanying orphanage staff, there were three thousand New Zealand and Australian soldiers returning home from the European front.

The children were again split into groups and allocated bunkrooms. The sleeping quarters were large cabins with four levels of hammock bunks. With the dexterity of a gymnast Tony climbed to the top bunk, having thrown his miserable bundle of possessions on the bed. Above each hammock there was a small shelf for personal belongings. The boy looked at it, but there was nothing he could put there. He had no family photo, no personal treasures, nothing but a change of clothes in his bundle.

When everyone had claimed their berths it was time for a wash. The bathrooms had long rows of showers. After the week-long trip through the tropics on a ship that had neither shower nor bathroom facilities, it was a real luxury to feel clean and cool.

Food was served twice a day, but not long after each meal Tony was hungry again. Sometimes the American sailors gave the children chewing gum or shared their chocolate allocation. One day there was ice cream for dessert. Tony took his bowl and hid in a corner away from the crowds, relishing the rare delicacy spoonful by spoonful.

During the trip across the Indian Ocean General Randall was escorted by four motor torpedo boats and two bombers, protecting the troopship from submarines and from other warships stationed in the waters in this part of the world. The navigators were on constant lookout for mines and for submarines firing torpedoes. One night a strong thud shook the ship, throwing the sleeping passengers off their bunks. Tony woke up on the floor of the cabin. In the morning there was uproar amongst the crew and the passengers, everybody excitedly recounting the experiences of last night.

As it turned out, the ship had been in great danger. A Japanese submarine had fired a torpedo at General Randall. Fortunately one of the escorting planes had sent a warning in time for the ship to alter its course, narrowly avoiding a disaster. The torpedo just brushed the side of the boat, giving it a big jolt but otherwise causing little damage.

If it wasn’t torpedoes and submarines, it was the stormy waters throwing the passengers about their cabins. One evening an announcement was made through the loudspeakers. Like most of the children, Tony didn’t understand a word because the announcements were in English. Later somebody explained a big storm was expected that night. Everyone was supposed to go to their cabins and keep the doors closed.

Tony soon fell asleep and didn’t even feel the violent rocking of the boat, but in the morning he woke up on the floor with a big bump on his forehead. For the next few days he wore a beret to hide the unsightly lump.

The trip went on and on. Apart from daily prayers led by Father Wilniewczyc or the nuns there were no activities organised for the children. They had to organise their own time. As on the first leg of their sea journey, the children enjoyed watching the crew at work. The boys in particular were fascinated by gun-crew training drills, or they looked out for submarines and torpedoes.

Among the American crew of the ship there were some descendants of migrants from Poland who spoke good Polish. Whenever they could the sailors spent time with the children, telling jokes and stories. Some gave them playing cards and taught them how to play a few games. Tony soon learned several games and spent hours playing cards with other boys, which helped to pass the time during the long journey.

The New Zealand and Australian returning servicemen also liked to play with the children, the language barrier quickly disappearing during ball games and skipping-rope activities. The boys liked playing soccer, but the New Zealand soldiers introduced them to a different game called rugby, played with a strange, oval ball.

Towards the end of the voyage fresh water became scarce and the passengers could no longer find relief in refreshing showers. The exertions of the long trip began to take its toll, and many children became sick and weak.

From time to time Tony went up to the top deck to scan the horizon for any signs of land. But no matter how long he squinted into the distance there was no land in sight – just water, endless water in all directions. Sometimes a giant fish with a pointy nose would jump out of the sea arching its back, but a moment later it would disappear under the surface, leaving only the vast expanse of shimmering water.

Then one day a cry came from the deck: “Land! Land!”

Everybody rushed to the top deck, wanting to see it for themselves. “Land! Land!” the cry was passed from lips to lips. It was Australia.

The ship called in to Melbourne, where the Australian soldiers disembarked and then the journey continued to New Zealand. Finally, on 31 October 1944, after a three-week journey across the Indian and the Pacific Oceans, USS General G.M. Randall reached Wellington.

From a distance New Zealand looked just as Tony pictured it in his mind green, lush and new.

Alone; p140- 145

In Iran, the children were preparing for departure. Though most of them knew nothing about New Zealand or where it was, many tried to impress other children with presumed knowledge, with snippets of usually imaginary “facts”.

One of the most horrifying stories doing the rounds was that cannibalism was still practiced there. The adults knew only that it was “at world’s end” and only a few volunteered to accompany the children. The orphans were given no choice and were resigned to being taken wherever they were sent. The frequent journeying over long distances was now part of their lives. To them it was important to be together with their new friends, with whom they had formed strong family-like bonds.

The older children were aware of being sent even further away from their native land and that they will have to part with some of their friends. But they understood and accepted the reasons for this. However, many adults experienced a real dilemma of not knowing what to do – to go even further away from Poland or stay put in an uncertain situation? Perhaps the next transports out of Iran will surely not be so far away from Poland? Malwina Rubisz-Schwieters, who was with her mother in Isfahan, recalls:

“After the Battle of Monte Cassino my father wrote to abandon any thoughts of a return to Poland because it will not be the same Poland that we knew. He wrote that New Zealand is a beautiful country – therefore go there. If I survive I will join you there. After my mother showed this letter to other adults, some of the women decided to go to New Zealand.”

In July and August of 1944 rumours began circulating that some of the children – mostly orphans, whose mothers died in Russia from starvation and some of whose fathers and elder brothers joined the Polish army-in-exile – were to leave for New Zealand under the care of approximately 100 personnel. Some adults wanted to leave Iran immediately. Others preferred to stay behind until the war’s end for a speedy return to Poland. Fr Michał wanted to stay, expecting an imminent end to the war and a quick return home. When told that he was to accompany more than 700 children to New Zealand as their spiritual director, he tried to have someone else go in his place. He justified it with the poor state of his health. He reminded the authorities that his friend Fr Franciszek Tomasik, who worked with him in Isfahan, wanted to go with the children. But it was decided to send a younger man and Fr Michał became one of those whose life became linked with the Pahiatua Polish orphans in the “land of the kiwi bird”.

Before leaving, he thanked the benevolent and kind-hearted Armenians for their hospitality to the Polish refugees in Isfahan’s suburb Julfa. The farewell took place in the local church in the presence of the Armenian apostolic administrator Jean-Baptiste Abcar. Addressing the Poles, he spoke of Poland’s martyrdom and of Armenia’s suffering, mentioning the more than one million of its people murdered by the Turks during World War I. In translating from the French, Fr Michał thanked his people for their generosity and welcome to the Poles, mindful that it was the Armenian church of Our Lady of the Rosary which was the centre of the Polish refugees’ religious life in Isfahan and the place of their heartfelt prayers, tears, cries of despair, pleadings to God and where regular novena’s were recited for their beloved and suffering homeland. He once again recalled how the Poles and Armenians joined together in celebrating the holy days at the altar.

The day before departure, on his name-day (in Poland more popular than a birthday), Fr Michał spent his time saying goodbye to the remaining personnel in the various establishments. The following day he was on one of the buses taking more than 700 orphans and accompanying personnel over a 545 km tortuous road from Isfahan to a transit camp in the Iranian town of Ahvaz. A further 131 km journey took them to the Iranian seaport of Khorramshahr. On 4 September 1944 they departed Iran on the British merchant ship Sontay (captured from the French navy, which had sided with the Germans).

The children were accompanied by teachers, educators, medical staff and two nuns of the Ursuline Order (all of whom were also refugees from Russian captivity). The nuns accompanying Fr Michał were Sister Maria Alexandrowicz (Sister Monika) and Sister Anna Tobolska (Sister Imelda), who had run a sanatorium in Isfahan. The medical staff comprised Dr Eugenia Czochańska and the dentist Dr Janina Budzyna-Dawidowska, who were accompanied by seven nurses. To maintain a vibrant and active Scouting movement and not waste the hard work in its establishment in Iran, Stefania Kozera was sent with the children as Scout leader.

Some of the children were told of their destination only in the last moments before departure for New Zealand. One of the girls recalls:

“After some time I found out that I was leaving for New Zealand, which did not make an impression on me, because I had no idea where the country was. I was issued from the store things necessary for the journey – socks, a comb, shoes, sheets, towels, soap, toothpaste, shoelaces and a blanket. I also possessed a nightgown, robe, a woollen hat and a pair of ‘drawers’ in a tiny satchel given to me in the hospital in Tehran. I was greatly enriched after receiving my travel accessories. Someone gave me a cardboard suitcase. I packed my things and waited for departure. For a time, I was transported from one establishment to another and finally to Establishment No. 20, from where transports departed for New Zealand. Buses took us to Ahvaz and then to a seaport where we boarded an English cargo ship. We walked down into a stifling hold with heavy mattresses stacked high in a boxing ring. We dragged these mattresses onto the deck because it was impossible to sleep in the airless cabin below. At six in the morning we were woken by deckhands calling out: ‘Six o’clock, washing deck!’ None of us understood the words but we learned fast when we were hosed down with sea water.”

The Sontay was a small ship, unsuitable for carrying such a large number of passengers, especially children. But it was the fastest mode of transport to Bombay in India. Two of the children on the ship, Stefania (nee Sondej) and Józef Zawada, recall:

“After a few days we were taken by buses to the seaport at Khorramshar where we boarded a British merchant ship the Sontay. We sailed slowly and carefully down the Tigris and Euphrates estuaries into the Persian Gulf, arriving in a war zone. Our ship was armed with only one large gun, which made a huge impression on us. This ship took us to Bombay.”

The voyage to India was without serious incident and they didn’t encounter any Japanese submarines. One of the passengers, Dioniza Choroś (nee Gradzik), recalls:

“The deck became our bedroom, dining room and recreation area. We carried our food from the kitchen to the deck. We dragged our mattresses onto the deck and slept under the stars. We sympathised with the small children who were not permitted to sleep outside. After breakfast an English officer showed us how to don the lifejackets properly. One day we were hit by a terrible storm and most of us were sick. Ashen faced and dirty children lay about the deck, not asking for help and not receiving any because our guardians were also ill.”

On 14 October 1944 the Sontay arrived in Bombay and docked near an enormous American troop carrier, the USS General Randall, in which the Poles were to sail to Wellington. This is how one of the children remembers the moment of boarding that ship:

“In Bombay we were almost immediately transferred to that ship which was to carry us to New Zealand. I think it was on that same day. Maria Wypych (nee Węgrzyn), who ministered to the smallest children, told me that there was no barrier up the gangway – the little children, up to five years old, were ill or convalescing and had to be guided by adults, one leading the child by the hand, the other following behind. Many prayers went up to heaven for the safety of the children during those moments.”

The ship sailed on the next day. It carried American, Australian and New Zealand soldiers returning to their countries on leave – many were wounded. The presence of so many Polish children on board was a great surprise to the soldiers, who very quickly made contact with them, from which life-lasting friendships were born, because the small orphans needed male role models and the soldiers (many of them fathers themselves) were reminded of the home life they left behind by going to war. They gave the children their rations of sweets and soft drinks. One girl remembers these moments:

“Gripping tightly our handbags, we walked in pairs behind a sailor of Polish origin with good knowledge of our mother tongue – his name was Chester Wisniewski. He was our interpreter and intermediary. We entered a large hall where we saw rows of four-tier hammocks. The younger children and boys had similar sleeping accommodation. We were given two meals each day, breakfast and lunch. At the entrance to the dining hall lay heaps of steel trays, which we carried along a row of standing cooks. As we went from one cook to the other they piled tons of food onto our trays, which even a wrestler couldn’t eat. Leftovers were put into containers. After our recent hunger in Soviet Russia, and a great respect for food, we couldn’t understand that so many God’s gifts were thrown away. Because the children, especially the younger ones, quickly became hungry again, big cans of milk were put out in the evening from which the children could drink until they could drink no more. The soldiers gave away their rations of chocolate.”

The voyage across the Indian Ocean to Melbourne was for the children a time of relaxation, adventure and making new friends. One of the girls, Henryka Aulich-Blackler, wrote: “We rehearsed a Polish regional dance, the Krakowiak, and took part in a Polish concert for the benefit of the captain.” Much of the entertainment was organised by the children themselves. Some boys were keen to learn mechanics and began “fixing” onboard equipment, causing damage and almost bringing on a crisis. From then on guards were posted around the more sensitive installations. The soldiers and sailors taught the boys many things, among them boxing, in which some of the boys showed great talent.

The New Zealanders returning from the war in Europe spent much time with the children. They played games and taught them English. One soldier took it upon himself to teach some girls New Zealand’s national anthem, which they later sang on the way to Pahiatua, where the surprised locals commented that the Polish children knew the anthem better than their own children.

Among all the joy aboard that troopship there were moments of terror. The war was still being fought and Japanese submarines patrolled the waters of the Indian Ocean. Sister Stella (nee Józefa Wrotniak):

“We sailed under an armed escort that guarded us from Japanese submarines. But our ship was hit by a torpedo. We could hear gunfire and the blare of alarm sirens. There was much terror and uncertainty onboard. The soldiers said that the children’s prayers had saved us.”

Another child remembers those moments:

“A torpedo brushed against the ship’s side. I was near the kitchen and there was a terrible clamour – all the drawers flew out. No one wanted to tell us anything. Some children fell out of their hammocks and chairs were overturned. In the morning the captain confirmed the rumours that we were hit, something which the older girls knew about all along.”

Everyone on board was instructed what to do in case of an emergency. The ship zigzagged over the water and changed direction every eight minutes. Our interpreter announced each evening over the loudspeakers “Time for the blackout!” and everyone had to go below deck and turn out the lights. The ship was veiled in darkness. Passengers were divided into groups and when the alarm sounded everyone had to run to their allotted lifeboats. In those moments of terror the adults had their hands full, constantly checking on the safety of their young charges. Fr Michał was seasick most of the time but continued to celebrate Mass each day and administered the sacraments. A group of the older children with Fr Michał and the nuns often organised collective prayers on the ship.

The convoy accompanying the troopship to Melbourne was large, with four destroyers and another troopship, a twin to the children’s ship. The troopships, one of which carried Australian soldiers to Melbourne, were a safety valve for each other. In case one sank, the other would take the survivors. Fortunately nothing happened and the ships arrived safely in Melbourne where the Australians disembarked. The ships separated at that point and the USS General Randall sailed alone a further 2,500km across the Tasman Sea to Wellington, New Zealand, where it arrived in the evening of 31 October 1944.

A Priest’s Odyssey; p79-83

Photos

Map

Documents

Acknowledgements

The New Zealand Museum Gallery Room “Polish Refugees in New Zealand – Deportees Forcibly Taken to Siberia, Ex-Servicemen and Displaced Persons” was created by a workgroup from Wellington, New Zealand under the umbrella of the Kresy-Siberia Foundation. The group was led by Irena Lowe (Smolnicki), and assisted by Dr.Theresa Sawicka, Wesław Wernicki, Jackie Rzepka, Adam Manterys and Mary-Anne Morgan (Baziuk).

Theresa and Wesław have provided the team with professional assistance in the field of history. Irena, Jackie, Adam and Mary-Anne are all first generation New Zealanders and descendants of family members forcibly deported from Kresy during World War II, who subsequently came to New Zealand either as children bound for Pahiatua Children’s Camp, or as ex-servicemen and women or displaced persons.

We also acknowledge all those Pahiatua children and adults, ex-servicemen and women, displaced persons and New Zealanders who have written about their own or their family’s experiences in books and journals and provided a wonderful history in text, photos and documents over many decades. The team has not set out to rewrite the history but rather to collate the existing stories in a structure so that the interested readers and the following generations can access the stories on-line and view the history as a mosaic. We are humbled by their experiences.

We are grateful to our sponsors who have enabled the publication of this gallery.

Stowarzyszenie Polskich Kombatantów SPK (Polish Ex-Servicemen’s Association)

Polish Charitable and Educational Trust New Zealand

The Morgan Foundation

Dr Zbigniew Popławski – in memory of the Popławski family

Andy and Anthony Bogacki – in memory of the Bogacki and Zielinski family

Eugenia Smolnicka – in memory of Michał and Antonina Piotuch

Jackie Rzepka – in memory of the Rzepka family

Steve Witkowski – in memory of the Witkowski family

Bibliography

Sources

Alexandrowicz, S.Monica 1998. “Z Lubcza na Antypody“. Seria: Ocalić od zapomnienia -1. Zgromadzenie Siótr Urszulanek SJK.

Beaupré-Stankiewicz, Irena, Danuta Waszczuk-Kamieniecka, and Jadwiga Lewicka-Howells. 1989. Isfahan – City of Polish Children. 3rd ed. London: Association of Former Pupils of Polish Schools, Isfahan and Lebanon.

Beaupré-Stankiewicz, Irena, Danuta Waszczuk-Kamieniecka, and Jadwiga Lewicka-Howells. 1987. Isfahan – Miasto Polskich Dzieci. 1st ed. London: Kolo Wychowanków Szkól Polskich, Isfahan i Liban.

Chibowski, Ks. Andrzej. 2012. Kapłańska Odyseja Ząbki. Original language edition. Polska: Apostolicum.

Chibowski, Dr. Andrzej. 2013. A Priest’s Odyssey. 1st English- language edition. Wellington, New Zealand: Future Publishing.

Dabrowski, Stanislaw. 2011. Seeds in the Storm. Waikanae, NZ: Maurienne House.

Ducat, Michelle, Mealing, David, Sawicka Theresa, and Petone Settlers Museum. 1992. Living in Two Worlds: The Polish Community of Wellington Wellington: Petone Settlers Museum/Te Whare Whakaaro o Pito-one

Jagiello, Józef. 2005. One Man’s Odyssey. Edition 2005. Józef Jagiello.

Department of Labour, New Zealand Immigration Service. 1994. Refugee Women: The New Zealand Refugee Quota Programme. Wellington: Department of Labour, New Zealand Immigration Service.

Lowrie Meryl. 1981 The Geneva Connection, Red Cross in New Zealand. Wellington: New Zealand Red Cross Society.

Manterys, Adam, Stefania Zawada, Stanislaw Manterys, and Józef Zawada. 2008. New Zealand’s First Refugees: Pahiatua’s Polish Children (2nd ed.). Wellington: Polish Children’s Reunion Committee.

Manterys, Adam, Stefania Zawada, Stanislaw Manterys, and Józef Zawada. 2012. New Zealand’s First Refugees: Pahiatua’s Polish Children (3rd ed.). Wellington: Polish Children’s Reunion Committee.

Manterys, Adam, Stefania Zawada, Stanislaw Manterys, and Józef Zawada. 2006. Dwie Ojczyzny: Polskie dzieci w Nowaj Zelandii Tułacze wspomnienia. Warszawa: Społeczny Zespól Wydania Książki o Polskich Dzieciach w Nowej Zelandii.

New Zealand Education Deptment. 1945. “Polish Children in New Zealand.” New Zealand School Journal, 1937-vol. 39 No 5, Part III:147-152.

Polish Women’s League. 1991. Wiązanka myśli i wspomnie / Koło Polek = A Bouquet of thoughts and reminiscences. Wellington, N.Z.: The League.

Rodgers, Owen. 2011. Adventure Unlimited – 100 years of Scouting in New Zealand 1908-2005. Wellington: Scout Association of New Zealand.

Ronayne Chris. 2002. Rudi Gopas – a biography. David Ling Publishing Limited.

Skwarko, Krystyna. 1972. Osiedlenie Młodzieży Polskiej w Nowej Zelandii w r. 1944. Londyn, Poets’ and Painters’ Press.

Skwarko, Krystyna. 1974. The Invited. Wellington: Millwood Press.

Spławska, Władysława Seweryn. 1993. Harcerki w Zwiądzku Harcerstwa Polskiego: Poczatki i Osiągnięcia w Kraju oraz 1939-1949 poza Krajem. Głowna Kwatera Harcerek ZHP poza Krajem.

Suchanski, Alina. 2006. Polish Kiwis: Pictures from an Exhibition. Christchurch: Alina Suchanski.

Suchanski, Alina. 2012. Alone : an inspiring story of survival and determination. Te Anau, N.Z.: A. Suchanski.

van der Linden, Maria. 1994. An Unforgettable Journey. Second Revised ed. Palmerston North: Dunmore Press.

Tomaszyk, Krystine. 2004. Essence. Palmerston North: Dunmore Press.

Tomaszyk, Krystyna. 2009a. Droga i Pamięć: Przez Syberie na Antypody. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Trio.

Zdziech, Dariusz. 2007. Pahiatua – “Mała Polska” małych Polaków. “Societas Vistulana” .

Other Books

Beck, Jennifer, and Lindy Fisher. 2007. Stefania’s Dancing Slippers. Auckland: Scholastic New Zealand. [Children’s Book]

Domanski, Witold (Vic). 2011. A New Tomorrow: A story of a Polish-Kiwi family. Masterton, NZ: Tararua Publishing.

Jaworowska, Mirosława. 2011. Golgota i Wybawienie: Dzieci Pahiatua od Syberii do Nowej Zelandii – Cztery Pory Roku jak Cztery Pory Życia Warszawa: Studio Jeden.

Kałuski, Marian. 2006. Polacy w Nowej Zelandii. Toruń, Poland: Oficyna Wydawnicza Kucharski.

Lochore, R. A. 1951. From Europe to New Zealand: An Account of our Continental European Settlers. Wellington: A. H. & A. W. Reed in conjunction with the New Zealand Institute of International Affairs.

Lubelski, Katolicki Uniwersytet. 2007. Z Sybiru na drugą półkulę : wojenne losy Polskich dzieci z Pahiatua. Lublin: Wydawn. KUL.

Pobóg-Jaworowski, J. W. 1990. History of the Polish settlers in New Zealand, 1776-1987. Warsaw: CHZ Ars Polona.

Ogonowska-Coates, Halina. 2008. Krystyna’s Story: A Polish refugees journey. Dunedin: Longacre Press.

Roy-Wojciechowski, John, and Allan Parker. 2004. A Strange Outcome: The Remarkable Survival Story of a Polish Child. Auckland: Penguin Books.

Szymanik, Melinda. 2013. One Winter’s Day in 1939. Auckland: Scholastic. [Children’s Book]

Turol, Sophia. 2010. Sophia’s Challenging Journey: Self-published.

Wiśniewska-Brow, Helena. Give Us This Day. Victoria University Press.

Other Materials

CraftInc. Films. 2015. Polish Children of Pahiatua. 70th Reunion – HD. Wellington: CraftInc Films. Produced by Wanda Lepionka and David Strong. [Film].

Gillis, Willie Mae. 1954. The Poles in Wellington, New Zealand. Edited by Department of Psychology. Vol. No. 5 Publications in Psychology. Wellington: Victoria University College. [Research]

Krystman-Ostrowski, Teresa Marja. 1975. The Socio-Political Characteristics of Polish Immigrants in Two New Zealand Communities, Department of Politics, University of Waikato, Hamilton. [Thesis]

National Film Unit. 1944. Weekly Review 169. Wellington: National Film Unit.

O’Brien, Kathleen. 1966. The Story of Seven-Hundred Polish Children. Wellington: New Zealand National Film Unit. [Film]

Ogonowska-Coates, John Anderson in collaboration with Halina. 1996. Exiles: The Story of a Polish Journey. Wellington: Ace of Hearts Production in Association with Polish Television. [Film]

Sawicka-Brockie, Theresa. 1987. Forsaken Journeys, Department of Anthropology, Auckland University, Auckland. [PhD Thesis]

Stowarzyszenie Polaków w Christchurch. 2004. Poles Apart: Historia 733 Polskich Sierot. Christchurch: Canterbury Telivision (CTV). [Film]

Tomaszyk, Krystyna. 2009b. The Story of the Polish Children in Isfahan – Iran 1942-1944. [DVD]

Indexes Of Names

Dundalk Bay – Ship carrying Displaced Persons to New Zealand

Goya Voyage 2 – Ship carrying Displaced Persons to New Zealand

Goya Voyage 3 – Ship carrying Displaced Persons to New Zealand

Orphanage – Pahiatua – New Zealand

S.S. “RANGITIKI” – Ship carrying ex-servicemen related to Pahiatua orphans to New Zealand

SS Hellenic Prince – Ship carrying Displaced Persons to New Zealand

Contact

Kresy-Siberia (New Zealand)

PO Box 853 Wellington 6140 New Zealand

e-mail: NZ@Kresy-Siberia.org