Polish Refugees in New Zealand 1944-1951

Exhibitions

Holidays

The City of Wanganui organised a paddle steamer boat trip down Wanganui River as one of the many activities organised by the city for the visiting Polish children. August 1945. Source: Polish Reunion Committee 2004.

Krystyna Skwarko: In order to help the children get acquainted with the New Zealand way of life and to tighten the bond of friendship the Catholic hierarchy and the New Zealand Army collected 830 invitations from New Zealand families for the Polish children and adults to spend two weeks’ holiday with them in August, 1945, and in January, 1946.

So the Poles dispersed over both islands where they formed many close friendships that frequently continued to last to the present day. (p71)

… With their unselfish kindness and hospitality the New Zealanders won the hearts of the Polish people and gained their appreciation for being in New Zealand. The Poles were soon to learn that the friendly New Zealanders were resourceful, not afraid of hard work and always ready to help their neighbours in need, whether at home or in another less fortunate country.

The Invited; p71

Voices

Voices

My admiration and gratitude extend to the hundreds of New Zealand families who welcomed the children into their homes for school holidays.

New Zealand First Refugees Pahiatua’s Polish Children (3rd edition); p42

On our holidays we were billeted out to New Zealand families and I was sent to a farm. The experience was unforgettable – animals, orchards and the general smell of the farm. The farmer was very kind and he took me and Jan Lepionka to the town in his car and bought us ice creams in a cone. I thought I was in heaven. The farm was such a fun place. Even today, when the stresses of life get too much, I transport myself mentally to this farm and this helps me to handle life

New Zealand First Refugees Pahiatua’s Polish Children (3rd edition); p97

To New Zealand. On 27 September 1944 we left Isfahan with its warm and sunny climate, which had helped us to regain our strength and health.

I will never forget Iran a country of mosques, palaces, gardens and shops full of decorative silver and copper.

New Zealand’s First Refugees: Pahiatua’s Polish Children (3rd edition); p69

While looking through a box of memorabilia I came across my very first autograph book. It was given to me during the May holidays in 1945. I still remember the train ride from Pahiatua to Inglewood and a nice lady with two girls waiting to meet us.

Thinking back, my admiration for that brave woman grows with time. Not too many people would be willing to invite into their home a complete stranger from an orphanage who does not speak their language, but this lady took two of us. Actually, many New Zealanders volunteered and the train was crowded with the inhabitants from the Polish Children’s Camp in Pahiatua. We all had tags attached to us with our names, destination and names of the families where we would be staying.

New Zealand First Refugees Pahiatua’s Polish Children (3rd edition); p100

I was billeted to a New Zealand family in Masterton for the holidays.

They were a lovely family, treating me like one of their own. One day they took me to the pictures to see A Californian Gold Rush and I can distinctly recall the main scene for the song Clementine. Every time I hear that song I can still vividly see the movie scene as I first saw it. We would gather around the piano and sing the songs. It was a marvellous time and like all good things it eventually came to an end.

New Zealand First Refugees Pahiatua’s Polish Children (3rd edition); p119

I was simply terrified when I was sent for my first two weeks’ holiday to some strange place called Pungarehu in Taranaki.

I didn’t want to go but I had no option. And my English was nil. I waited at the station for a long time with my name tag pinned to my dress and strange women passing by looking at my card and moving on. “Dear God,” I prayed, “let someone come soon” because I was close to tears. At last a woman stopped, studied my card and said “come”.

New Zealand First Refugees Pahiatua’s Polish Children (3rd edition); p211

I recall once when we were paired off and sent to different destinations for a holiday to experience life with New Zealand families. I forget who my friend was, but I suspect he was as scared and mystified about the whole thing as I. A group of us arrived by train in Wanganui and we waited at the station for our New Zealand hosts to pick us up. My friend and I were the last ones to be collected. We snuggled into a corner and waited. It was dark and we weren’t too sure how long we had to wait.

Eventually our hosts identified us by our tags and we were taken to their homes. They were lovely, hospitable people who fed us well and looked after us beautifully. They showed us off to their friends and we generally had a great time. Our command of the English language was very limited at that time but we must have managed to communicate. These holidays were repeated a few times and I am very grateful to our New Zealand hosts for their generosity.

New Zealand First Refugees Pahiatua’s Polish Children (3rd edition); p143

In general, the New Zealand families welcomed us into their homes, especially during the school holidays. We helped out on the farms and earned a little pocket money.

New Zealand First Refugees Pahiatua’s Polish Children (3rd edition); p172

In May 1945, six months after our arrival in New Zealand, we spent our school holiday with New Zealand families to experience everyday life and improve our English. My journey began at Pahiatua Railway Station and ended in Masterton, while others continued their journey to New Zealand families in different parts of the country. I well remember how shy and awkward I felt standing on the platform, awaiting some kind family to take me to their home. It was quite unnerving.

But soon some of my apprehension was dispelled. I noticed a lovely lady with a big smile holding a card with my name on it and walking towards me. She took me by the arm and said “Welcome to Masterton” and led me to her car. We travelled for about half an hour before reaching the family home. The house was large with a very pretty garden and a neat green lawn. There was also a sizeable vegetable garden. They were sheep farmers.

The family consisted of a mother, father, two daughters and one son. They greeted me warmly on arrival and were very kind throughout my two-week stay. We had a lot of laughs trying to understand one another. I have very fond memories of my first holiday in New Zealand.

The evening meal was a special time, as they changed to more formal dress. Dinners were very tasty and for the first time in my life I had roast lamb, roast pumpkin and mint sauce. The desserts were delicious.

One evening, something embarrassing happened at the dinner table. One of the girls at the table asked: “Romualda, pass the salt please.” My answer was: “No thank you.” I thought she had offered me salt, which I did not need. What a blunder I had committed.

I sometimes think of that particular evening and hope that they took my comment with “a grain of salt”.

New Zealand First Refugees Pahiatua’s Polish Children (3rd edition); p191

The news spread through the camp like wild-fire. Come the May school holidays the camp will only have a skeleton staff looking after the children , as the majority of us are going to be sent out to various NZ families for the holidays. What excitement and apprehension! At last the day arrived. We were all dressed in our khaki uniforms, navy coats and berets, and of course, name tags on our coat lapels.

I was sent to a family in Hastings. The family consisted of five children (people with the least, always seem to have the biggest hearts) so one extra did not make much difference and the children helped to break the ice.

It was an unforgettable experience as our English consisted of “thank you”, “please”, “good-morning” and “I don’t understand!” What patience and kindness was shown by the whole family to me as we tried to communicate for the smallest thing with the aid of my trusted English Polish dictionary. I tried to learn English and in tum they made an attempt at learning a few Polish words.

The laughter still rings in my ears at their attempt to say “prosze”* that somehow always sounded like “prosie”*. It was on one of the many school holidays that I spent there that I learned the difference in the sounds of “I had a hat on my head”. Until then “had, hat” and “head” all sounded exactly the same and kept me wondering what they were trying to teach me!

I shall never forget how special they made me feel when they came all the way from Hastings to Pahiatua armed with sweets, biscuits and fruit just to spend a few hours with me.

I was in Napier for a holiday in 1945 when the end of the war was announced . The jubilation, celebrations, singing, hugging and kissing were endless. Of course I was sure that I would be on the next boat going back to Poland and apprehensive at the fact that I had nobody to go back to.

The Foddy family are still my family and my friends after 45 years. We have kept in touch and kept track of things that have happened in our lives, the lives of the five children and my adopted Mum and Dad. They will always remain a part of my life, of my childhood and adulthood, and my first steps in New Zealand.

* Prosze – please

* Prosie – piglet

Bouquet of Thoughts and Reminiscences; p52,54

Following is an English translation of a delightful little essay which appeared in the newspaper of the Polish Children’s Camp at Pahiatua.

“It is six years since we have seen Poland, but Almighty God has watched over us wherever we have been. We have had many sad moments in foreign countries, until fate took us to New Zealand. We are very happy here, working and learning our lessons, because we know that our country will need us. New Zealanders look after us well, and show us much kindness. There came a day when we were to spend our holidays with New Zealand families. Terrific excitement in the camp, packing our suitcases and preparing for our journey.

I and my friend Zosie went by train via Masterton to stay with Mr. and Mrs. C. The beautiful surroundings of Masterton reminded me of some towns in Poland. We were welcomed with great hospitality and shown our rooms. During the first few days we did nothing but sleep and eat good things.

Later we had much fun and visited many other people. We were having such an enjoyable time that we forgot lessons and camp life. I used to get up at 10 a.m. and of to bed at 10 p.m., a very pleasant change from getting up at 6:30 a.m. in the camp.

Before breakfast, I said “Good Morning” to the parrot, but it did not understand Polish, so I tried to teach it to say “Dzien Dobry,” but it was too hard for it to learn. After breakfast I used to read books, and write letters to my friends in camp until lunch time.

On nice days after lunch we used to sit under the trees in the garden and talk to Mrs.C., all of us laughing and joking a great deal. We were very happy.

We had plenty of visitors, and later I would go down to the fowls and the birds in their cages, and I rode a bicycle.

In the evenings when it was getting cold, Mrs. C., would call us into the house and we sat on the sun porch watching sunset. I heard the rustling of the trees and the twittering of the birds and imagined myself back in Poland, but it was not Poland, but good, kind, New Zealand.

After a good dinner we would visit other houses or play at home until 10 p.m. On one occasion I saw a concert with a Highland band and dancing, which I enjoyed very much. There were great celebrations in Masterton on VJ-Day, and I liked the Maori dancing and singing. I had a lovely time, but unfortunately the day of departure came all too soon.

We will always remember our good kind hosts. We will always retain them in our memories for their considerations, for our comfort and enjoyment, making every moment of our holiday in their home perfect”.

The Geneva Connection, Red Cross in New Zealand; page 81

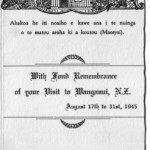

Fifty years ago Wanganui provided the first large-scale direct contact with the New Zealand way of life for 225 children from the Polish Children’s Camp in Pahiatua. They stayed from 17 to 31 August 1945. With the help of the army, along with charitable and church groups, Wanganui became a huge holiday camp.

When the Polish children came here by special train, each had a tag with their name and host. With junior Chamber of Commerce members on the platform calling out instructions, it was a bewildering introduction to the river city for the war victims who were aged from five to about 15.

New Zealand First Refugees Pahiatua’s Polish Children; p192

Christmas marked the beginning of the summer holidays. Younger children were invited to stay with New Zealand families, to give them a taste of real New Zealand life. Some of those New Zealanders happened to be of Polish descent. There was a large Polish community in Taranaki, where many early Polish settlers made their home. The Sacred Heart Catholic Church in Inglewood was frequented each Sunday by the Poles from the Taranaki area.

In January 1945 a group of boys and girls from the Pahiatua camp were invited to Inglewood. On the day of their departure they were taken to the Pahiatua train station by one of the army trucks from the camp’s fleet. A cardboard label on a piece of string around the neck of each child had the name and address of their host on one side, and the child ‘s name on the other. Once the youngsters boarded the train the conductor came by and inspected their tags to ensure he delivered them to the right places. As the train trundled across the North Island the conductor helped each of his young passengers get off at the right station.

Tony, Michael Smal and Nikifor Piesocki were going to spent two weeks on a dairy farm near Inglewood run by Mr Drozdowski, a farmer of Polish descent. After a few hours on the train they were put down on the platform of the Inglewood station together with other boys and girls destined to disembark at this place. The hosts, who had been waiting at the station for their young guests, now checked the labels to see which children were for them.

A short middle aged lady approached and quickly found the three girls who were staying with her. She then turned to the boys and started checking their tags. Having identified Tony, Michael and Nikifor as being the ones she was looking for, she said in clear, although rustic, Polish: “Good day, I’m Mrs Campbell. You girls will be staying with me and I’m taking you boys home with me as well. You’ll spend your first night with us and tomorrow you’ll go to my brother’s farm. Let’s go ‘ She started walking and the children followed her, carrying their suitcases. “My brother’s friend will pick you up tomorrow,” she said to the boys. At home she gave the children a big meal and sent them off to bed.

The next morning Tony and his friends were picked up by an old farm truck. They threw their suitcases into the back of the truck, piled into the cab and off they went to Tariki, twelve kilometres south of Inglewood.

On their way they noticed a huge mountain on their right. You could hardly ignore it for it was the only protrusion in the otherwise flat farm land. The boys had seen mountains before, but this one was different. Usually they were grouped into ranges, with many peaks close to one another like the teeth of a saw.This one was a single peak of perfectly conical shape, standing tall above the surrounding flat landscape. Beside it were two hills of the same shape but smaller, resembling children holding on to their mother’s skirt. The “mother” mountain was so high its peak was piercing the clouds that hung around it like a scarf.

“That is Mount Egmont,” the driver explained. “It’s a volcano.”

“Can it explode?” Tony wanted to know.

“Rather unlikely. It’s been extinct for a very long time:’

It was late afternoon when they reached the farm. The driver pressed the horn a few times as he pulled up in front of the house. He stopped the truck and the boys jumped out and dragged their suitcases off the back. ‘The homestead was a colonial-style weatherboard building with a verandah all around. Tall pine trees in a single file surrounded the house and the garden, providing shelter from strong winds.

A short stocky man walked out to greet the visitors. “Good day, boys;’ he said in Polish. “Welcome to my farm:’ He waved to his friend, who drove off in his truck. “Thanks, mate. See you later”.

Peter Paul Drozdowski was a single man approaching forty. He had inherited the farm at the foot of Mt Egmont from his parents, who immigrated to New Zealand in 1876 and settled in Inglewood. The Drozdowski family was quite numerous, with twelve siblings, some of whom were still living in the area. Peter Drozdowski’s parents spoke Polish at home and kept in touch with their relatives back in the old country. ‘They had passed away in early 1940s, but their descendants continued the tradition of Polish hospitality. Mr. Drozdowski invited his guests into the house and gave each boy a cup of milk with a slice of country bread. When they had rested a little after their trip, the host showed them to their rooms. Niki and Michael shared one bedroom and Tony had a bedroom to himself.

“Make yourselves at home, boys. When you’ve unpacked I’ll show you around.’

Exploring Mr. Drozdowski’s farm brought back memories of Poland. It was teeming with domestic animals including chicken, geese, ducks, goats, horses, oxen, and a herd of cattle. Behind the house was a vegetable garden plus a few fruit trees.(p160-163)

… Although born in New Zealand, Mr. Drozdowski spoke good Polish, even if it was a little dated. Some of the expressions he used were specific to the area in northern Poland his family came from, and made the boys laugh. “Okay, boys;’ he would say in the evening, “time to go under the goose mountain.’

The boys looked at each other puzzled the first time he said this. “What do you mean?” they asked.

“I mean it’s time to go to bed.’

“I get it,” Niki said. “The goose mountain is our duvet.” (p163-164)

… For the boys, staying on the farm was paradise. It reminded them so much of their life in Poland. They were eager to lend a hand to their host, remembering the same jobs being done back home with everybody helping from an early age. It was just what they would have done during summertime in Poland.

Mr. Drozdowski worked very hard on the farm. He lived alone and did all the work himself. He fixed fences, herded the cattle, attended to all other animals, trimmed the trees, worked in the veggie garden, and even did all the cooking, washing and cleaning. In the morning he made breakfast for the boys, then gave them some jobs to do and went off to work on his farm. Around noon he called them for lunch and at six o’clock he served dinner. The food at Mr. Drozdowski’s was even better than at the Pahiatua camp. There were luxuries, such as cream with the porridge, or fried rather than boiled potatoes, or delicious beef sausages.(p164)

… The two weeks spent on the farm went fast and soon the boys had to go back to the camp. Mr Drozdowski visited the Pahiatua camp a few times, hoping to find a wife, but he was unlucky in this respect. Tony stayed with the old Pole three times, twice during the summer holidays in January and once during the winter holidays in August. (p166)

Alone; p160-163, 163-164, 164

By summer 1946, when our group of healthy seemingly happy, and lively Polish boys arrived for their country holiday, we knew that most of them would grow up in New Zealand.

The Geneva Connection, Red Cross in New Zealand; page 81

Documents

Acknowledgements

The New Zealand Museum Gallery Room “Polish Refugees in New Zealand – Deportees Forcibly Taken to Siberia, Ex-Servicemen and Displaced Persons” was created by a workgroup from Wellington, New Zealand under the umbrella of the Kresy-Siberia Foundation. The group was led by Irena Lowe (Smolnicki), and assisted by Dr.Theresa Sawicka, Wesław Wernicki, Jackie Rzepka, Adam Manterys and Mary-Anne Morgan (Baziuk).

Theresa and Wesław have provided the team with professional assistance in the field of history. Irena, Jackie, Adam and Mary-Anne are all first generation New Zealanders and descendants of family members forcibly deported from Kresy during World War II, who subsequently came to New Zealand either as children bound for Pahiatua Children’s Camp, or as ex-servicemen and women or displaced persons.

We also acknowledge all those Pahiatua children and adults, ex-servicemen and women, displaced persons and New Zealanders who have written about their own or their family’s experiences in books and journals and provided a wonderful history in text, photos and documents over many decades. The team has not set out to rewrite the history but rather to collate the existing stories in a structure so that the interested readers and the following generations can access the stories on-line and view the history as a mosaic. We are humbled by their experiences.

We are grateful to our sponsors who have enabled the publication of this gallery.

Stowarzyszenie Polskich Kombatantów SPK (Polish Ex-Servicemen’s Association)

Polish Charitable and Educational Trust New Zealand

The Morgan Foundation

Dr Zbigniew Popławski – in memory of the Popławski family

Andy and Anthony Bogacki – in memory of the Bogacki and Zielinski family

Eugenia Smolnicka – in memory of Michał and Antonina Piotuch

Jackie Rzepka – in memory of the Rzepka family

Steve Witkowski – in memory of the Witkowski family

Bibliography

Sources

Alexandrowicz, S.Monica 1998. “Z Lubcza na Antypody“. Seria: Ocalić od zapomnienia -1. Zgromadzenie Siótr Urszulanek SJK.

Beaupré-Stankiewicz, Irena, Danuta Waszczuk-Kamieniecka, and Jadwiga Lewicka-Howells. 1989. Isfahan – City of Polish Children. 3rd ed. London: Association of Former Pupils of Polish Schools, Isfahan and Lebanon.

Beaupré-Stankiewicz, Irena, Danuta Waszczuk-Kamieniecka, and Jadwiga Lewicka-Howells. 1987. Isfahan – Miasto Polskich Dzieci. 1st ed. London: Kolo Wychowanków Szkól Polskich, Isfahan i Liban.

Chibowski, Ks. Andrzej. 2012. Kapłańska Odyseja Ząbki. Original language edition. Polska: Apostolicum.

Chibowski, Dr. Andrzej. 2013. A Priest’s Odyssey. 1st English- language edition. Wellington, New Zealand: Future Publishing.

Dabrowski, Stanislaw. 2011. Seeds in the Storm. Waikanae, NZ: Maurienne House.

Ducat, Michelle, Mealing, David, Sawicka Theresa, and Petone Settlers Museum. 1992. Living in Two Worlds: The Polish Community of Wellington Wellington: Petone Settlers Museum/Te Whare Whakaaro o Pito-one

Jagiello, Józef. 2005. One Man’s Odyssey. Edition 2005. Józef Jagiello.

Department of Labour, New Zealand Immigration Service. 1994. Refugee Women: The New Zealand Refugee Quota Programme. Wellington: Department of Labour, New Zealand Immigration Service.

Lowrie Meryl. 1981 The Geneva Connection, Red Cross in New Zealand. Wellington: New Zealand Red Cross Society.

Manterys, Adam, Stefania Zawada, Stanislaw Manterys, and Józef Zawada. 2008. New Zealand’s First Refugees: Pahiatua’s Polish Children (2nd ed.). Wellington: Polish Children’s Reunion Committee.

Manterys, Adam, Stefania Zawada, Stanislaw Manterys, and Józef Zawada. 2012. New Zealand’s First Refugees: Pahiatua’s Polish Children (3rd ed.). Wellington: Polish Children’s Reunion Committee.

Manterys, Adam, Stefania Zawada, Stanislaw Manterys, and Józef Zawada. 2006. Dwie Ojczyzny: Polskie dzieci w Nowaj Zelandii Tułacze wspomnienia. Warszawa: Społeczny Zespól Wydania Książki o Polskich Dzieciach w Nowej Zelandii.

New Zealand Education Deptment. 1945. “Polish Children in New Zealand.” New Zealand School Journal, 1937-vol. 39 No 5, Part III:147-152.

Polish Women’s League. 1991. Wiązanka myśli i wspomnie / Koło Polek = A Bouquet of thoughts and reminiscences. Wellington, N.Z.: The League.

Rodgers, Owen. 2011. Adventure Unlimited – 100 years of Scouting in New Zealand 1908-2005. Wellington: Scout Association of New Zealand.

Ronayne Chris. 2002. Rudi Gopas – a biography. David Ling Publishing Limited.

Skwarko, Krystyna. 1972. Osiedlenie Młodzieży Polskiej w Nowej Zelandii w r. 1944. Londyn, Poets’ and Painters’ Press.

Skwarko, Krystyna. 1974. The Invited. Wellington: Millwood Press.

Spławska, Władysława Seweryn. 1993. Harcerki w Zwiądzku Harcerstwa Polskiego: Poczatki i Osiągnięcia w Kraju oraz 1939-1949 poza Krajem. Głowna Kwatera Harcerek ZHP poza Krajem.

Suchanski, Alina. 2006. Polish Kiwis: Pictures from an Exhibition. Christchurch: Alina Suchanski.

Suchanski, Alina. 2012. Alone : an inspiring story of survival and determination. Te Anau, N.Z.: A. Suchanski.

van der Linden, Maria. 1994. An Unforgettable Journey. Second Revised ed. Palmerston North: Dunmore Press.

Tomaszyk, Krystine. 2004. Essence. Palmerston North: Dunmore Press.

Tomaszyk, Krystyna. 2009a. Droga i Pamięć: Przez Syberie na Antypody. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Trio.

Zdziech, Dariusz. 2007. Pahiatua – “Mała Polska” małych Polaków. “Societas Vistulana” .

Other Books

Beck, Jennifer, and Lindy Fisher. 2007. Stefania’s Dancing Slippers. Auckland: Scholastic New Zealand. [Children’s Book]

Domanski, Witold (Vic). 2011. A New Tomorrow: A story of a Polish-Kiwi family. Masterton, NZ: Tararua Publishing.

Jaworowska, Mirosława. 2011. Golgota i Wybawienie: Dzieci Pahiatua od Syberii do Nowej Zelandii – Cztery Pory Roku jak Cztery Pory Życia Warszawa: Studio Jeden.

Kałuski, Marian. 2006. Polacy w Nowej Zelandii. Toruń, Poland: Oficyna Wydawnicza Kucharski.

Lochore, R. A. 1951. From Europe to New Zealand: An Account of our Continental European Settlers. Wellington: A. H. & A. W. Reed in conjunction with the New Zealand Institute of International Affairs.

Lubelski, Katolicki Uniwersytet. 2007. Z Sybiru na drugą półkulę : wojenne losy Polskich dzieci z Pahiatua. Lublin: Wydawn. KUL.

Pobóg-Jaworowski, J. W. 1990. History of the Polish settlers in New Zealand, 1776-1987. Warsaw: CHZ Ars Polona.

Ogonowska-Coates, Halina. 2008. Krystyna’s Story: A Polish refugees journey. Dunedin: Longacre Press.

Roy-Wojciechowski, John, and Allan Parker. 2004. A Strange Outcome: The Remarkable Survival Story of a Polish Child. Auckland: Penguin Books.

Szymanik, Melinda. 2013. One Winter’s Day in 1939. Auckland: Scholastic. [Children’s Book]

Turol, Sophia. 2010. Sophia’s Challenging Journey: Self-published.

Wiśniewska-Brow, Helena. Give Us This Day. Victoria University Press.

Other Materials

CraftInc. Films. 2015. Polish Children of Pahiatua. 70th Reunion – HD. Wellington: CraftInc Films. Produced by Wanda Lepionka and David Strong. [Film].

Gillis, Willie Mae. 1954. The Poles in Wellington, New Zealand. Edited by Department of Psychology. Vol. No. 5 Publications in Psychology. Wellington: Victoria University College. [Research]

Krystman-Ostrowski, Teresa Marja. 1975. The Socio-Political Characteristics of Polish Immigrants in Two New Zealand Communities, Department of Politics, University of Waikato, Hamilton. [Thesis]

National Film Unit. 1944. Weekly Review 169. Wellington: National Film Unit.

O’Brien, Kathleen. 1966. The Story of Seven-Hundred Polish Children. Wellington: New Zealand National Film Unit. [Film]

Ogonowska-Coates, John Anderson in collaboration with Halina. 1996. Exiles: The Story of a Polish Journey. Wellington: Ace of Hearts Production in Association with Polish Television. [Film]

Sawicka-Brockie, Theresa. 1987. Forsaken Journeys, Department of Anthropology, Auckland University, Auckland. [PhD Thesis]

Stowarzyszenie Polaków w Christchurch. 2004. Poles Apart: Historia 733 Polskich Sierot. Christchurch: Canterbury Telivision (CTV). [Film]

Tomaszyk, Krystyna. 2009b. The Story of the Polish Children in Isfahan – Iran 1942-1944. [DVD]

Indexes Of Names

Dundalk Bay – Ship carrying Displaced Persons to New Zealand

Goya Voyage 2 – Ship carrying Displaced Persons to New Zealand

Goya Voyage 3 – Ship carrying Displaced Persons to New Zealand

Orphanage – Pahiatua – New Zealand

S.S. “RANGITIKI” – Ship carrying ex-servicemen related to Pahiatua orphans to New Zealand

SS Hellenic Prince – Ship carrying Displaced Persons to New Zealand

Contact

Kresy-Siberia (New Zealand)

PO Box 853 Wellington 6140 New Zealand

e-mail: NZ@Kresy-Siberia.org