“Holocaust” of Jews in Krzemieniec in 1942

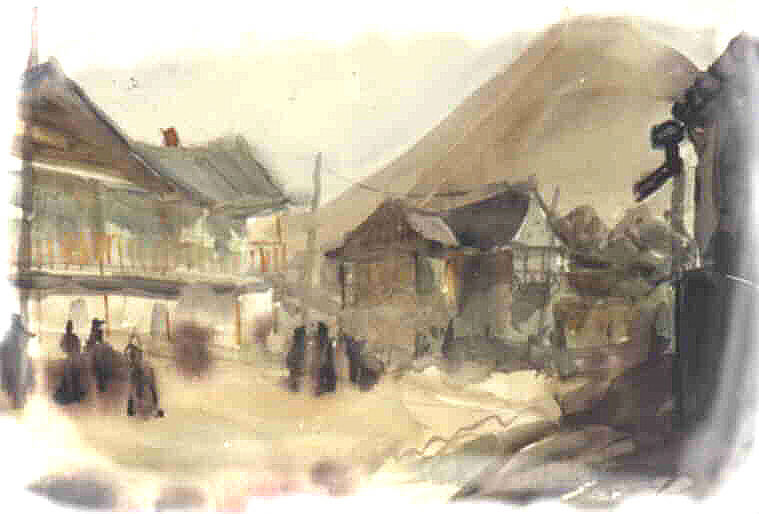

Jewish Homes in Krzemieniec by W. Tiunin

The Ghetto in flames, 1942

Ghetto in Ruins: A Ukrainian militiaman on guard, 1942

Jerzy Struminksi, in “Zycie Krzemienieckie,” Nr 12, 1996

The Hitlerites, shortly after entering Krzemieniec in 1941, set about organizing a ghetto for the Jews. They selected the center of town which was inhabited mostly by Jewish families as the area for the ghetto. Into this area they also crammed in Jews from other sections of the town. The ghetto was surrounded by a high fence along which walked patrols of German gendarmes and Schutzmanns (Ukrainian police working for the gendarmerie). Over 10,000 Jews were sealed in the ghetto along with escapees from the west, mostly from Lodz. The social strata was diverse. Next to a group of the rich and refugees from Lodz, the majority was comprised of pre-war poor. Alongside the local administration and the kahal[Jewish assembly of elders] the Germans organized a Jewish police.

The food allotment which the ghetto received from the Germans was of starvation rations and impounded severely on the poor. At the beginning there was a busy commerce between the ghetto and the surrounding area, through a hole in the fence and by a group of Jews who were led out on forced labour. The first injunction which fell on the ghetto was an order by the Gebits Komisarz for the Jews to dismantle their synagogue–their religious center. The synagogue on Szeroka Street was a massive building. The bricks taken from it by the hands of the Jews went to build German buildings. A smilar loss awaited the Jewish cemetery under Kredowa Mountain from where stone cemetery plates were shipped en masse.

The Gebits Komisarz for Krzemieniec, high-ranking thugs, realized that the Jews could be plundered of their gold and other valuables. The Jews, putting their faith in the power of gold and silver, believed they could save themselves by handing over their riches to the Germans. Thus entire wagons drove out of the ghetto full of gold in all its forms, and then silver such as chandeliers, jewelry boxes and other items. But the sources quickly ran out.

In the summer of 1942, the Gebits Komisarz left for a “well-earned vacation.” In its place arrived the next group of Hitler’s thugs from the Gestapo. In the eyes of Himmler they were to fulfil a supreme role: the liquidation of the Krzemieniec ghetto. And so it began. The ghetto was closed and surrounded by gendarmes and Schutzmanns. Next commenced the blind and random shooting of the ghetto on two occasions. The aim of this was to psychologically break and crush the Jews in preparation for the imminent “holocaust.” During this time farewell dinners took place among the wealthier Jews, sometimes ending with a familial ingesting of poison. The random shooting of the ghetto didn’t claim many victims, but it did extinguish the inhabitant’s sense of self-preservation. It turned the people into “unresisting animals being led to slaughter.”

It was a beautiful sunny day when word spread that trucks covered with boards were taking Jews out of the ghetto somewhere to Dubienska Rogatka. I learned from inhabitants at the town center that trucks were entering the main gate of the ghetto into which Jews were being loaded and then driven out. The tragedy of the Jews was compounded by the fact that to the gendarmes and Schutzmanns dragging people from their homes and chasing them to loading points, were added Jewish militia armed with clubs. Probably the Hitlerites had promised them that they could save their lives in this manner, but in the end this was not the case. That evening they too were taken to the place of “holocaust” in the last trucks.

At noon word spread that the mass shooting of Jews was taking place at the mouth of the gully at the western slope of Mount Kuliczowka. Many people headed for the mountains, to which I added myself. From the mountains could be observed “Dantesque” scenes unfolding at the base (about 200 meters in a straight line). The word “Dantesque” in this case was inadequate as for Dante it was a fantasy, but here one could witness the actual crime of mass murder on a scale never before experienced, and which later would be given the Hebrew word “Holocaust.” Following the first shock of witnessing the scenes unfolding at the mountain’s base, the nature of human psychology is such that in time it accomodates itself, and the ensuing scenes were to be viewed as some macabre film.

The area that the Hitlerites had chosen for the killing grounds was on the road from Krzemieniec to Mlynowce along the Ikwa River where a Tsarist shooting range remained from World War One. The range, over 100 meters long and tens of meters wide, was surrounded on three sides by banks and was accessible only from the road. A ditch 8-10 meters wide and dozens long had been prepared. Along the ditch were barrels full of what probably was chlorinated lime. Along the banks stood armed gendarmes and Schutzmanns.

The process of extermination was as follows. Each arriving truck was surrounded by a group of gendarmes armed with whips. After being unloaded the people were herded to the so-called “change-room” where they had to undress to nakedness and to leave their clothing which later was thoroughly searched. Found was a great deal of gold, valuables, money etc. Then in single file, chased by the gendarme’s whips, they were conveyed to the execution ditch. Here in shifts two Gestapo men with pistols would carry out the “business.” They fulfilled the “supreme orders of Hitler and Himmler” by dispatching their victims with a shot in the back of the head. In order to “rationally” utlize every square meter of the ditch, the victims were killed so that they fell crossways on the layer of previous victims. The shot in the back of the head caused little blood so that the Gestapo men didn’t have to wade in blood. The spaces between the legs of the victims were filled by gendarmes with the bodies of murdered children.

During my several-hour stay on Kuliczowka Mountain, six butchers in shifts of two “worked” on the firing range. While two worked, four would sit at a table covered with food and bottles of vodka, and every now and then pairs would exchange duties. I have no doubt they were all drunk and that their aim must have been problematic. As evidence of effective psychological methods in crushing a person, is the fact that in my several hours of observing the executions, I saw only two cases of attempted escape. Some young men already herded into the death ditch tried to save themselves by escape. They made it over the bank of the firing range and ran into fields covered in corn which surrounded the range. Shots echoed from the bank. Did they manage to escape?–I don’t know. Another example was when one of the trucks filled with victims and their escorts, turned over after a sharp turn. This was an excellent chance for escape, yet no one tried. Gendarmes arrived to help and with their whips quickly drove everyone to the “change room” and then to the execution ditches. As the ditches would be filled with victims, a “funeral” would ensue. This consisted of white powder (chlorinated lime) being scattered by scoops after which the bodies would be covered by a layer of several centimeters of earth. In these conditions perished as well those whom the drunken Gestapo men had promised not an instantaneous death.

As I previously related, a person after a certain time can get used to what he sees–but to the end of my life certain scenes remain. For instance the scene of a naked woman with a small child in her arms and holding another older one by the hand, as she runs being beaten by a whip to the execution ditch. Or an old man with a long white beard chased to the same ditch.

That the Germans tolerated inhabitants of Krzemieniec sitting on the mountainside was intentional: a warning. I have no doubt that more than one of the observers (especially the Poles) thought in his soul: today the Jews–and after that us. And more than one felt: God where are You? Do You not also see? That day some 10,000 Jews perished. It was a beautiful sunny day, and above their communal grave rolled the blue of the sky.

In ending my account I add a few words about the end of the Krzemieniec ghetto. After the day of mass murder, the Hitlerites went through the ghetto for several weeks. During this time they transported out whatever was still valuable such as furniture, clothing, linens etc. One could also hear single shots and realize that those still hiding in the ghetto were being liquidated. In early September, the buildings of the ghetto were deliberately set afire at many points. The fire lasted several days after which remained just smouldering ruins.

Teodor Dubicki, Poland; in a letter to Janina Sulkowska. May 5, 1991

The Germans herded the Jews into the ghetto which was created in the confines of Pierackiego Street, Gorna Street and Szeroka Street, near the Renesans Cinema. The ghetto was surrounded by a wall, soundproofing and barbed wire. I was a chance witness to the liquidation of the ghetto and almost fell myself to a German bullet.

At the end of July 1942, around 6 p.m., I was walking to visit relatives on Pierackiego St. I was surprised to see that on the street in front of the entrance to the ghetto, there was a large number of German gendarmes who were setting up machine guns on the wall of the Krzemeniec Lyceum, pointing at the ghetto. Black clouds were gathering above the town as a storm was brewing. When I entered the house of my relatives, rain was coming down in buckets. The hour of police curfew was nigh–no returning home now. Together with lightning and thunder, the shooting of firearms exploded–into the windows of the ground floor came horrible screams, the breaking of doors, laments. This continued to dawn.

In the morning I beheld the ghetto in flames. During the night there had been a battle: the Germans were shooting, and the Jews as well. I returned home by a circuitous route that day. The fire consumed the entire ghetto which burned for three days and nights, and was visible far from Krzemieniec. After the fire, the Germans took Jews who had been hidden, in trucks to ditches near the train station where they shot them.

(For accounts of an uprising in the Krzemieniec Ghetto see: The Holocaust of Volhynian Jews, 1941-1944, by Shmuel Spector.)

Christopher Jacek Gladun was born in 1951 and grew up in Canada to where his family emigrated from England as displaced persons. Sadly, Chris died in Toronto in March 2003. He held a diploma in Journalism from the Niagara College and a BA in Polish Language & Literature from the University of Toronto. Chris also acted as interviewer and researcher for the documentary film “Rescued From Death in Siberia”.

This content is now maintained by the Kresy-Siberia Group, which Chris was a charter member of and which is taking his website and his research work forward.