In the Clutches of the NKVD in Krzemieniec

The jail was located near the train station on Rogatka Dubienska, off Szeroka Street, at the north end of town. A brick building built as a jail in Czarist times, it was designed for 150 prisoners, but during the Soviet occupation (September 1939 – July 1941) between 400 and 500 were jammed in at any one time as the result of NKVD arrests. The jail was run by NKVD personnel brought from the USSR while minor duties fell to local Ukrainians and Jews. NKVD headquarters with adjoining cells for interrogation, was at the other end of town in the former Polish police station. Those imprisoned were Poles, Ukrainians and some Jews. Estimates of prisoners killed by NKVD shootings and German bombardments in June 1941, vary from 150-1500. Jan Sulkowski spent five months here before shipment to the Gulag. Many of his friends and fellow-citizens met death in these cells. –Editor

At midnight a banging on doors. Several NKVD men burst in: “Hands up! Against the wall!” Searching for weapons they throw everything from cupboards and shelves, and scatter books. They order me to dress. Tears flow in my house as I leave with a package under my arm: bread, sausage, cigarettes.

The 5th of November, 1939–end of freedom.

Off to the NKVD headquarters where I undergo a search followed by a prison christening: beatings, kickings, and off to the cell. The next day several professors and army settlers are added. Once a day we receive soup and hot water.

Nov. 22 is grey and cloudy. In the prison yard await five peasant wagons. Shackled in pairs we are driven off to Krzemieniec. At the main gate of the jail are many wagons from the entire county with masses of those arrested. We’re wet, cold and hungry. Finally our group of forty is let in. Our shackles are removed and we’re ordered to strip, and then are searched thoroughly. Buttons are cut from our jackets, and belts and suspenders confiscated. We’re ordered to removes shoelaces and to unpack our packages. The food is cut into small bits, cigarettes are broken. We are told to dress and are marched into one wing of the jail. A corridor about 100 meters long with 43 cells from which bunks and blankets have been removed so that only four cement walls remain. On the floor is a layer of urine up to our ankles.

We’re almost 40 to a cell–even standing it’s hard to fit. Prisoners at the entrance are jammed in by doors. Many squat in the reeking liquid. Once a day 25 grams of bread and hot water. We can’t put down our clay bowls and keep them under our arms at all times. Sometimes we receive a soup of hairy cow ears, intestines and anuses. The NKVD does not invite us to the steam baths. For breaking regulations the punishment was seven days in the detention cell which measures 1 meter 20cms by 80cms–dark, cold and wet it is a prison within a prison. After serving time there a prisoner would be dragged back to his cell half-alive. In a nearby cell are 14 women, seven of whom are Polish and are mostly teachers from Krzemieniec Lyceum. They uneasily share the cell with seven Ukrainian female nationalists.

Weeks and months pass. In the winter of 1940 “Black Ravens” arrive and take us to the other end of Krzemieniec and NKVD headquarters. During periods of interrogation one could stay imprisoned for years. The psychologically weaker ones sign without reading the charges. Stronger ones are “persuaded” by

pistol-whipping. Women are not spared the interrogations. Sentences are severe: 8 to 12 years and even 18 years. And death.

The German-Soviet war. From the morning of June 26, 1941 a complete silence in the halls. Then is heard woeful screaming, shots and the groans of the murdered as the NKVD shoots prisoners. The NKVD then escape in guard vehicles to Jampol. A German air raid on Krzemieniec. Bombs fall on the jail and some of the cells are hit. The cries of the wounded mix with the sound of prisoners breaking down the doors and running to the exit. In the large yard surrounded by a high wall prisoners seek a way out. Inhabitants of Krzemieniec have gathered outside and with hammers they beat open the locks of the big gate. Dozens of prisoners are on the walls. The wounded are dragged out as prisoners carefully make it across barbed wire and jump down on green potato fields: “Faster–to Freedom!”

On the street many Soviet soldiers in chaotic retreat. They even act friendly to the prisoners, treating them to bread and newspapers. Freedom! The prisoners set out on the street to town. Others take shorter and safer routes into fields, forests and mountains. Fresh air revives them…

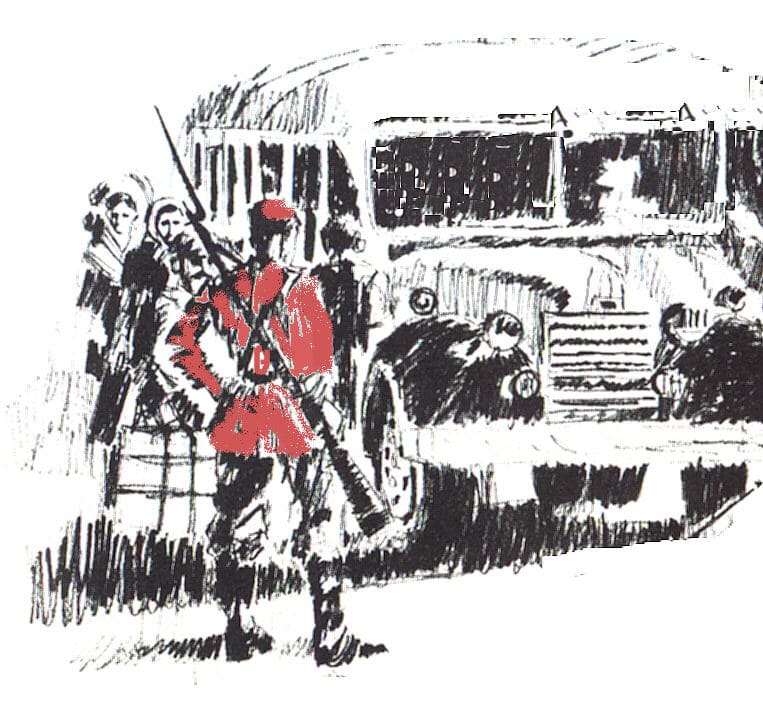

Suddenly another air raid. Bombs fall on the train station, hillsides, and norther part of town. But the main German forces bypass Krzemieniec. They are directed at Dubno, Rowne, Ostrog, Slawuta. They cut the rail lines at Shepetovka. The Soviet Army in a hurried march abandons Krzemieniec. But then from Jampol return the NKVD men with their leaders. Some of the prisoners are sneaking out via Dubienska St, trying to escape. The NKVD naczalnik junps out of his car–muddied, with papers in hand, and accompanied by his NKVD personnel. Shots! There are wounded, someone is killed, several prisoners escape! Then the captured are packed into trucks that set out for the jail. Here Soviet soldiers are helping inhabitants drag out the wounded from their cells. A sharp confontation takes place between the officer leading the soldiers and the NKVD naczalnik. The truck turns toward the NKVD building and delivers its prisoners. Escapees are hunted down for a few more days but 190 are unaccounted for. The jail once more is filled.

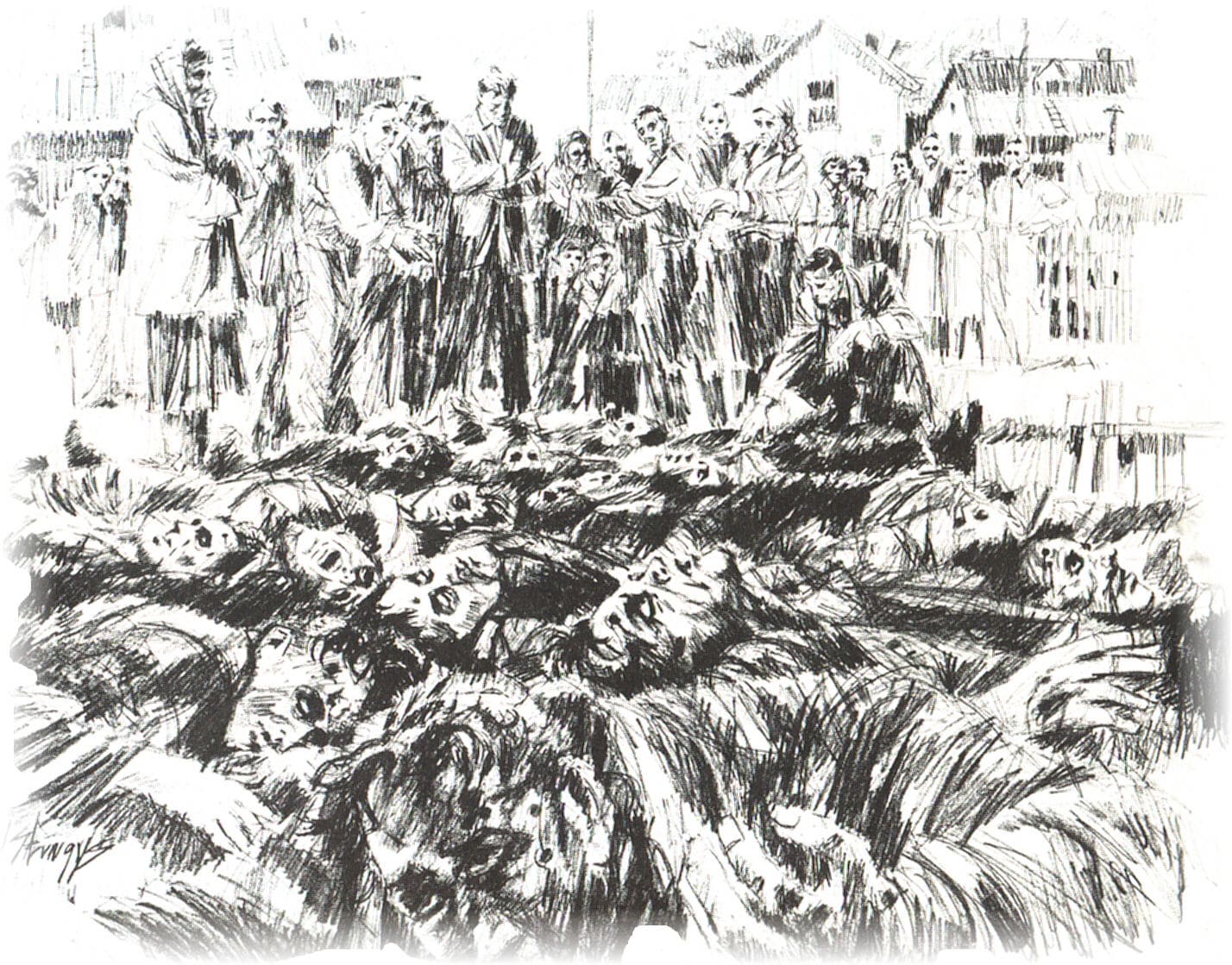

From June 28, prisoners in the jail are segregated by the staff. They burst into the cells at night, call out names and drag the prisoners into trucks which are driven to a nearby gully at Tunikach for execution.

At dawn of July 2, the gates are opened and remaining prisoners are ordered into the yard. Human shadows are placed into two columns. The inventory is checked and the command given. Thus commences the forced march of 136 people, including 6 women, to the USSR. Under escort of 20 NKVD men and 10 German Shepherd dogs, the prisoners are driven in fours down the middle of the road through Rybcze and Katerburg to Jampol. Many are hungry and weak. The sun burns, guards swear and the dogs bite. Those prisoners that fall behind are dispatched with a pistol shot. Then a station, Kiev and deportation into the Urals and the “Land of Happiness.”

The next day tanks with swastikas cover the same route. German gendarmes stop in a school building at Rybce just a few kilometers from Krzemieniec. The village is searched and from one cellar are led three Soviet soldiers and five Polish ones, three of them wearing older Polish uniforms. A hasty miltary trial: the Soviets are executed on the escarpment and the Poles on a hillside near a cross.

Teodor Dubicki, Poland – in a letter to Janina Sulkowska, May 5, 1991

The Soviet death sentence on several Krzemieniec Lyceum professors and students for belonging to a “Polish counterrevolutionary organization” was to be carried out on Sept.8, 1941. Others had received several years prison while some were sent to “guard” the bears. Many students suffered interrogations at night. At school we still had to pay one ruble each for the International Organization in Aid of Revolutianaries–whoever didn’t pay was sent to the “unknown.” After the deportations to Siberia in January, 1940, there were few students left in class.

But then a miracle: on June 22, 1941, the German “friends” attacked their

Soviet “friends.” The first few days of war saw panic by the Soviets in town–the jail staff and NKVD took off. The Germans were already in Poczajow and Dubno, their tanks broke through the old Polish-Soviet border near Ostrog.

During the panic and chaos in Krzemieniec, whoever could entered the jail and led out or carried the surviving prisoners. In the cells many shot prisoners were found. Those prisoners whom the NKVD had managed to load into wagons during the night of June 21-22 could not be saved. Their train bound for Kiev was bombed by the Germans. So a “voyager” told me. The escaped prisoners hid wherever they could, but then the NKVD–after their initial shock–returned to town and searched for them.

The Germans stopped at Poczajow and only took Krzemienec after three days following a battle at Zolob where they crushed the Soviet forces who were marching thousands of prisoners through town.

When the German army left the Krzemieniec front, detachments of the SS made up of Germans and Ukrainians (the infamous Nachtigall Brigade) entered the town. They carried out mass executions that included the professors and students who had escaped Soviet death, but for whom there was no sympathy even as former NKVD prisoners.

Christopher Jacek Gladun was born in 1951 and grew up in Canada to where his family emigrated from England as displaced persons. Sadly, Chris died in Toronto in March 2003. He held a diploma in Journalism from the Niagara College and a BA in Polish Language & Literature from the University of Toronto. Chris also acted as interviewer and researcher for the documentary film “Rescued From Death in Siberia”.

This content is now maintained by the Kresy-Siberia Group, which Chris was a charter member of and which is taking his website and his research work forward.