Poland’s Class of 1936

Synopsis / Background of Janka and her Memoir

A tribute to my mother’s heroic struggle for survival and search for loved ones under Nazi and Soviet genocide. An expanded reprint from The Toronto Star, Oct. 3, 1999 – Chris Gladun.

There were twenty-five proud graduates in 1936 from Krzemieniec High School, famous as Poland’s Eton. From their graduation photo they smiled confidently — university and illustrious careers awaited them in a Poland that had recently arisen from the ashes of World War One. A Nobel Prize in their chosen field was a legitimate ambition.

But those dreams would be shattered in 1939, and barely eight matriculants would survive World War Two.

Janina Sulkowska, my mother, was one of the lucky students. She was on her way to becoming an educator, but she never dreamt she’d be taking care of dying orphans in Persian and Indian refugee camps, or later conducting Polish language lessons in Canadian basements. “Janka” certainly never foresaw the years of imprisonment, suffering and permanent exile that would afflict her and her family and friends. My mother, who died in 1997 at age 83, spent the rest of her life lamenting her lost studies and crushed hopes, and searching for her missing classmates. Janka’s graduation photo became an icon of what befell Poland under the tyranny of Nazism and Communism.

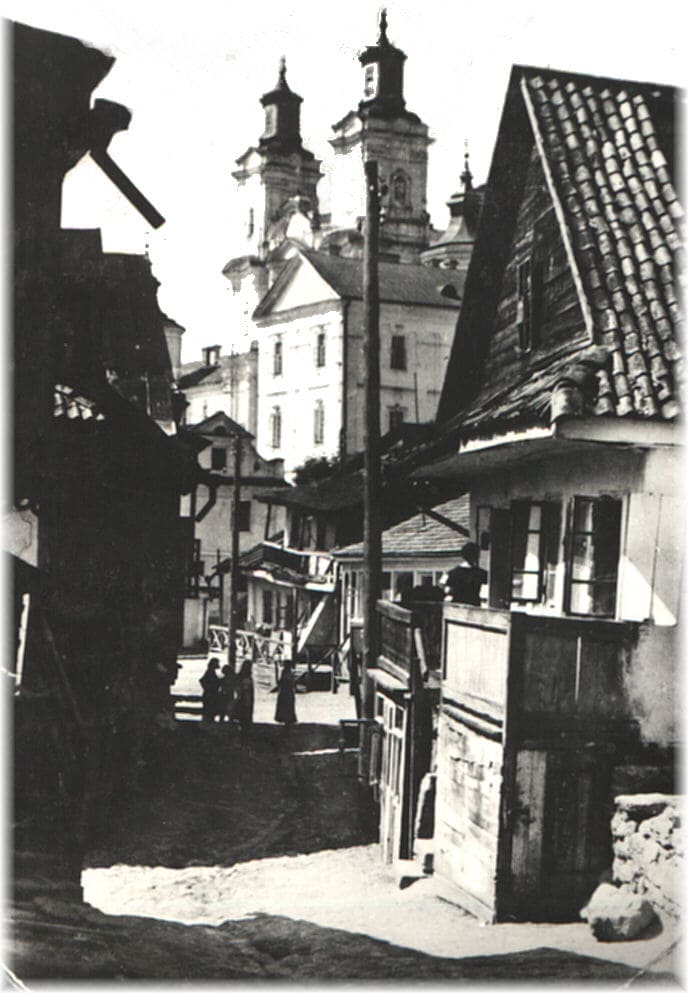

The city of Krzemienec (pop. 25,000) in southeastern Poland, was first terror-bombed by the Germans before being occupied on Sept. 18, 1939, by the Red Army, which immediately began a campaign of ethnic cleansing aimed at Poles. Thousands were brutally murdered, arrested or dispossessed of their property and positions. Janina’s beloved Krzemieniec High School was turned into a nightmare based on a Soviet model; teachers and students disappeared.

At the start of the war, Janina’s family helped the thousands of refugees streaming into the city escaping the Nazis, including many embassies from Warsaw. But her father Jan would be arrested by the Soviets and sentenced to labour camps for five years for associating with “kulaks” and “speaking of the low quality of Soviet goods.” His real crime was being Polish.

Jan would be deported to the USSR, and he would die in exile never again seeing his wife or youngest daughter. The family was split forever.

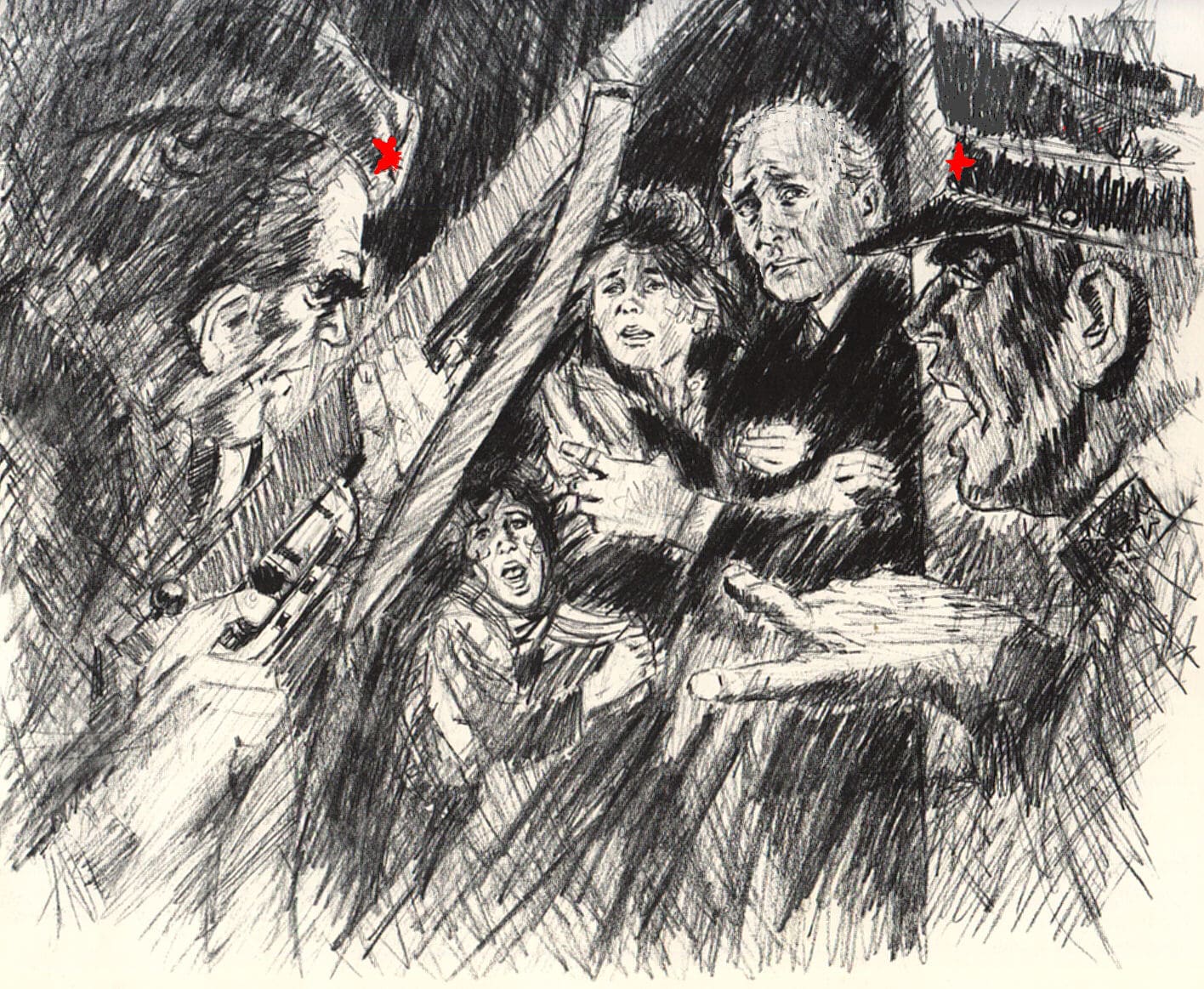

One night in early 1940, a Jew and a Ukrainian, both neighbours, burst into the Sulkowski home bringing a Soviet soldier with them. They gave Janka’s mother, brother and 14-year-old sister just thirty minutes to pack before herding them with bayonets and guard-dogs to the rail station where they were loaded into cattle cars on a train bound for Siberia. The Sulkowski property was divided among the collaborators and Soviets; what couldn’t be used, such as personal things and photos, were thrown into a fire.

NKVD Arrests: entire families were deported in cattle-cars to Siberia

Janka and Leon at their wedding

Similar terrible scenes were played out across Poland as hundreds of thousands were deported (estimates range from 1 million to 2 million)–the majority of them women and children, half of whom would die in exile. Entire families were taken to suffer together while others were broken-up forever. Close to a dozen of my relatives would perish at the hands of the Soviets and the Nazis. None of those who survived would ever return to Krzemieniec. Janka’s mother, sister and cousins were only allowed to come back to Poland in 1946, leaving behind many graves even as they struggled with their terrible memories.

Janina joined the Polish underground in 1939 along with many of her friends from Krzemieniec and Warsaw University. As a courier of secret information, she travelled between numerous cities in Soviet-occupied Poland in the guise of a student. But her organization was smashed in early 1940 by the NKVD (the Soviet equivalent of the Gestapo) and she was arrested along with most of her comrades. She would spend several years in Soviet prisons and in the outposts of the Gulag, including a severe punishment-camp where she was the very last female Polish prisoner. Janka would be close to death many times from torture, starvation and disease, but she made a promise to be reunited with, or at the least, discover the fate of her family, friends and prisoners she’d met. Even if it took the rest of her life.

Janina Sulkowska made it out of the USSR as a result of the “amnesty” issued by Stalin to exiled Poles, even if it was eight months later than everyone else, and she would be presumed long-dead by her family. After years in India and England, she emigrated to Canada in 1951 with her husband Leon Gladun, a friend from Krzemieniec and one of the few survivors of the Katyn massacres–and whose marriage was foretold to her by a Gulag “seer”. They settled in the city of St. Catharines, Ontario, Canada, where Janka was active in the Polish community and organizations. She would become a teacher of Polish language and a writer with her own children’s column for years.

For over half a century there would be inquiries on Janka’s part to discover the fate of her missing classmate and friends. Over the years, the back of her graduation photo became covered in scribbles and notes beside each name. Painstakingly, she searched for and recovered a handful of her classmates–scattered around the world, but alive. Sadly, most were dead or missing. Even as late as 1997, my mother was following leads all over the globe from Brazil to Australia to South Africa. She was also instrumental in organizing reunions of scattered Krzemiencians and Poles, as well as trying to help those still trapped in the USSR. I recall how at one reunion a middle-aged man approached my mother and with tears in his eyes asked if she was “Auntie Jasia, the teacher from India?” It turned out she indeed had taught a ten-year-old Polish orphan to regain his language and overcome his trauma. Still, my mother recounted to me that 90% of the people she’d met in the prisons and the Gulag, never made it out alive. One of her legacies is a memoir and large collection of letters chronicling her life and times which I am endeavouring to have published.

Alongside a dozen names, my mother reluctantly recorded the grim details of those classmates of 1936 who perished in the war. She said this made her feel like an accomplice in execution, and I know she shed many a silent tear. In one or two cases, victims were resurrected from the list of presumed dead, which gave her false hopes. “Perhaps he survived Siberia?” or “Maybe she outwitted the Gestapo?” my mother quipped against all odds.

A number of Janka’s classmates had given their lives in defence of Poland and in the Allied cause during WWII. Jerzy Golebiowski was killed in a burning tank at Warsaw fighting the blitzkrieg in the first weeks of the war. My mother had supplied Józio Maczynski with fake ID to escape from Poland; he went on to join the Royal Air Force in England and perished as a pilot in 1944, as did Mundek Jasinski–shot down over Germany. Bolek Lesniewicz was killed in action in Italy as a member of the Polish Second Corps. Olek Mioduszewski had been executed by the Soviets at Katyn in 1940 and Mietek Sobota fell victim as well, though his body was never found. Kazimierz Puzichowski returned from the front to be murdered along with his family by Ukrainian fascists. Igor Gryjelski perished in Siberia–or did he? So many had vanished “without a trace” and so many lay in umarked graves far from home. Every class of Krzemieniec High School could tell a similar story of sacrifice and suffering.

A number of Janka’s classmates had given their lives in defence of Poland and in the Allied cause during WWII. Jerzy Golebiowski was killed in a burning tank at Warsaw fighting the blitzkrieg in the first weeks of the war. My mother had supplied Józio Maczynski with fake ID to escape from Poland; he went on to join the Royal Air Force in England and perished as a pilot in 1944, as did Mundek Jasinski–shot down over Germany. Bolek Lesniewicz was killed in action in Italy as a member of the Polish Second Corps. Olek Mioduszewski had been executed by the Soviets at Katyn in 1940 and Mietek Sobota fell victim as well, though his body was never found. Kazimierz Puzichowski returned from the front to be murdered along with his family by Ukrainian fascists. Igor Gryjelski perished in Siberia–or did he? So many had vanished “without a trace” and so many lay in umarked graves far from home. Every class of Krzemieniec High School could tell a similar story of sacrifice and suffering.

Among the victims in Dubno was another family friend, 22-year-old Teresa Trautman. She had been arrested even though she was barely involved in underground work, and had attempted suicide in prison as a result of Soviet interrogations which included beatings and rape. Janka was forced to witness Teresa’s physical and psychological torture at the hands of the NKVD. My mother told me how she had listened as Teresa was taken for interrogation–her head thudding against each step of a stairway as the guards dragged her by the feet. My mother could still hear those horrible echoes years later.

After that final outburst in 1941, Soviet terror was supplanted by the Nazi brand as all of Poland was quickly occupied by the Germans. Janka’s family had been deported to the USSR, but friends and classmates still remained in Krzemieniec. The Nachtigall battalion arrived and immediately carried out executions: Jews, Poles and Ukrainians fell, including professors and students of Krzemieniec High. The Nazis set up a ghetto in town which they then “liquidated” in 1942. As many as 15,000 Jews, the entire Jewish population of Krzemieniec, were murdered and buried in mass graves.

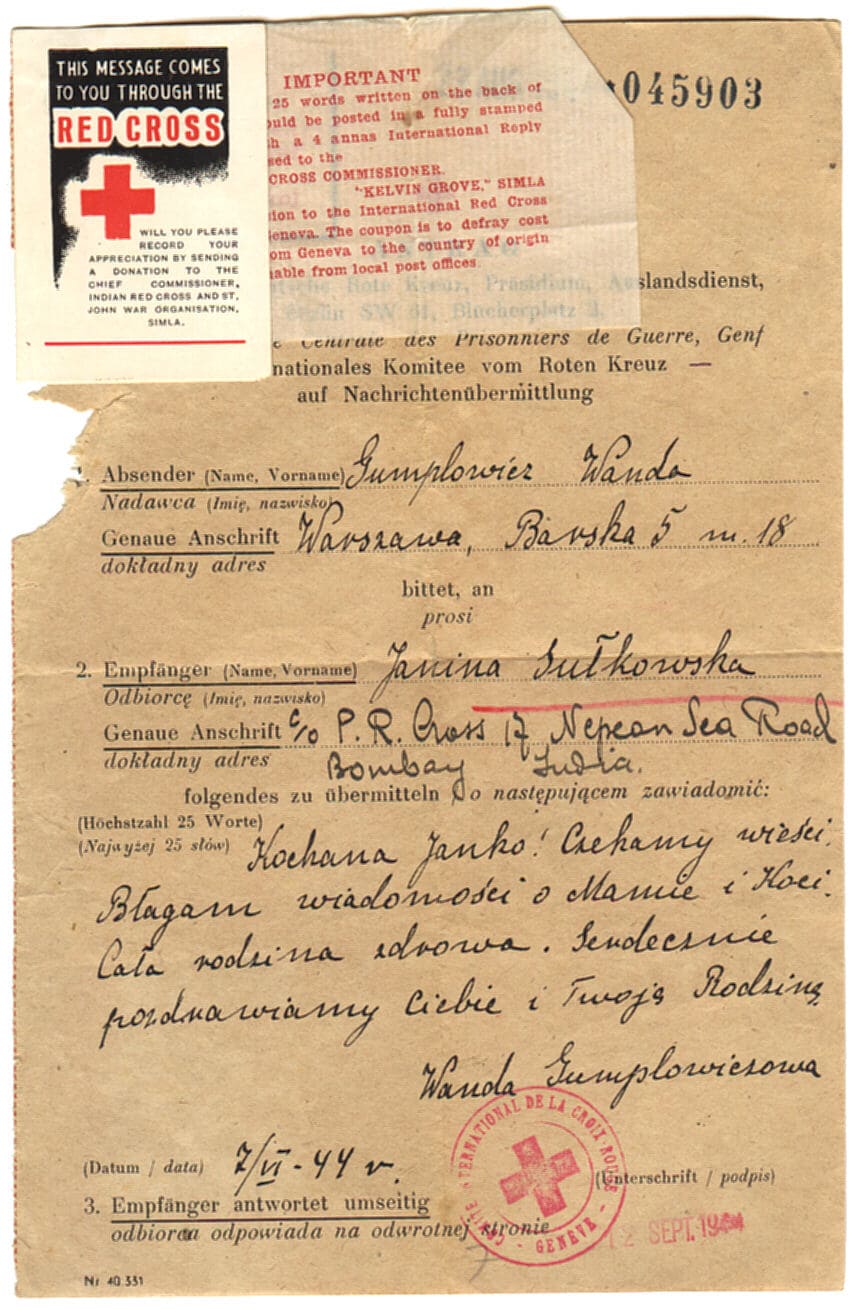

Red Cross Appeal from relatives in Nazi-occupied Poland to Janina in India, for news of family--several of whom were already dead or would shortly die.

Pilots of the Polish 303 Squadron. During the Battle of Britian, every eighth pilot was a Pole.

Jewish Ghetto aflame in Krzemieniec.

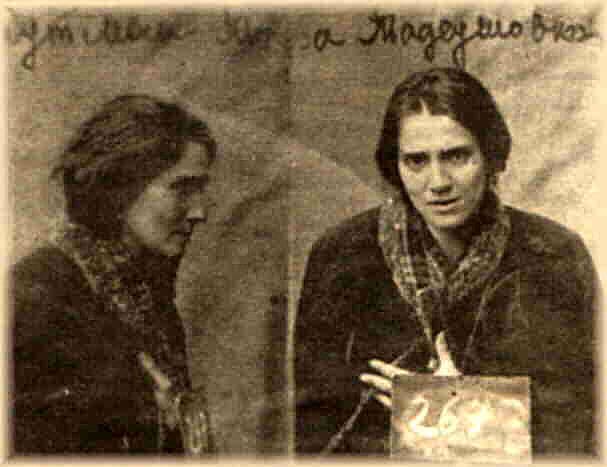

Teresa Trautman in a prison NKVD photo. Her body was recovered by her mother from Dubno jail even as Nazi sanitation crews were preparing the cells for more Polish prisoners.

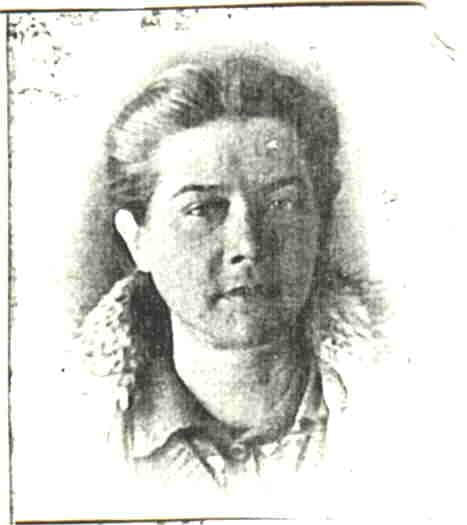

Janina, day of release from Gulag, 1942 -swollen from malnutrition.

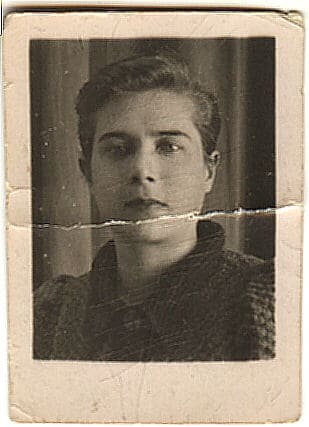

Janina, Teheran, 1943 - after malaria.

The Ghetto victims included Janina’s classmates and friends. Lejba Jaglym planned on being a great astronomer; my mother noted on the class photo that at age 26 he “had perished in the ghetto with family.” Abram Buc almost certainly met a similar fate but no confirmation could be found. Leon Szajnberg was fondly remembered as the class fujara or klutz; everyone Janka contacted insisted that undoubtedly he did not survive the Holocaust. Yet my mother kept a big question mark next to his entry. And in the late 1980’s she discovered that shy “Lowa” had made it–and had become a general in the Israel army! As for Chana Zamberz, she wrote: “went to France before the war–perhaps survived?”

The following classmates still have “fate unknown” or “vanished without a trace” after their names: Wojtek Kulesza, Leon Kowalec, Tamara Traczuk and Wanda Wlodarczyk. Janina wrote in her memoirs of countless frozen corpses “stacked like cords of wood” and how she wanted to commit suicide beneath a falling tree because everyone was gone. But she survived by reaching deep within herself in a promise not to betray them or their memory. And in life she started every day as if a soul missing for 50 years would turn up living next door! She kept hope alive with faded photos, rumours, and letters or phone calls from distant places.

But to the end of her life, my mother particularly agonized over the mystery of Lida Skrypnik. They were inseparable friends from Krzemienic High all the way through Warsaw University. The pair shared the modest goal of making the Polish educational system the best in the world, and were active in related causes and organizations until the war put a stop it.

Janina was arrested by the NKVD and tortured to reveal information about the underground; interrogators subjected her to sleep deprivation, Russian Roulette and an electric chair. Among the “evidence” was a postcard sent to her by Lida with the words “I believe in Werba”–a reference to the opening of a university. But to the NKVD this revealed a “counter-revolutionary” plot despite my mother’s denials. Lida subsequently disappeared and my mother could never forgive herself for letting that postcard fall into enemy hands. Janka searched endlessly for any trace of Lida but found nothing. I can only admire my mother for refusing to drop that heavy load of uncertainty and grief.

Perhaps someone, somewhere, knows what happened to Lida? Or has news of Chana or Wojtek? The fate of the 1936 Graduating Class from Krzemieniec High School tormented my mother for a lifetime, and today their still-youthful faces haunt me. Are there other children of the lost or searching out there? I know that Lejba was consumed by the Holocaust–but I believe that somehow he did become an astronomer, and is searching even now with his telescope that peers into hearts that believe and won’t forget.

Basia Poniatowska and Krystyna Krahelska, Krzemieniec, 1933. Krystyna was the model for the Warsaw Siren statue which symbolized Warsaw and the struggle against Nazism. Both Basia and Krystyna perished fighting in the Warsaw Uprising.

Krzemieniec Liceum

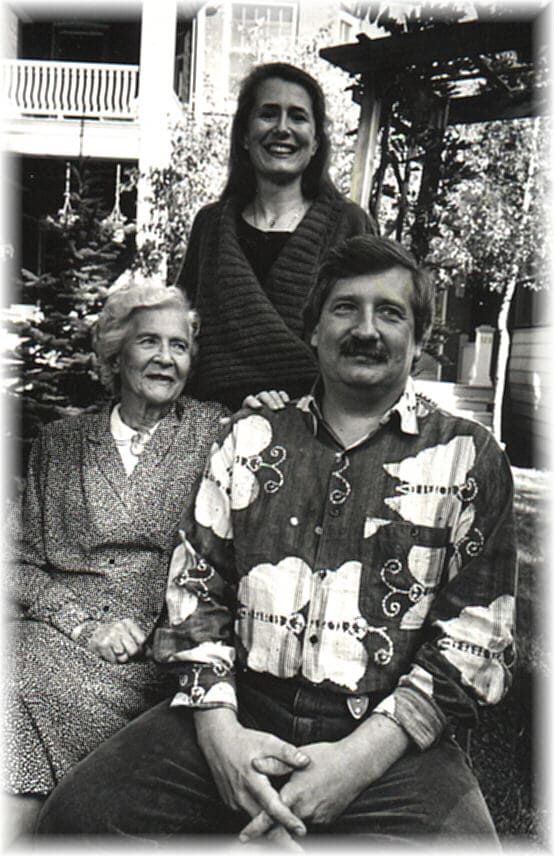

Janina Sulkowska with daughter Wanda and son Christopher, 1992.

Christopher Jacek Gladun was born in 1951 and grew up in Canada to where his family emigrated from England as displaced persons. Sadly, Chris died in Toronto in March 2003. He held a diploma in Journalism from the Niagara College and a BA in Polish Language & Literature from the University of Toronto. Chris also acted as interviewer and researcher for the documentary film “Rescued From Death in Siberia”.

This content is now maintained by the Kresy-Siberia Group, which Chris was a charter member of and which is taking his website and his research work forward.