The Letters of Natalia and Wanda Sulkowska

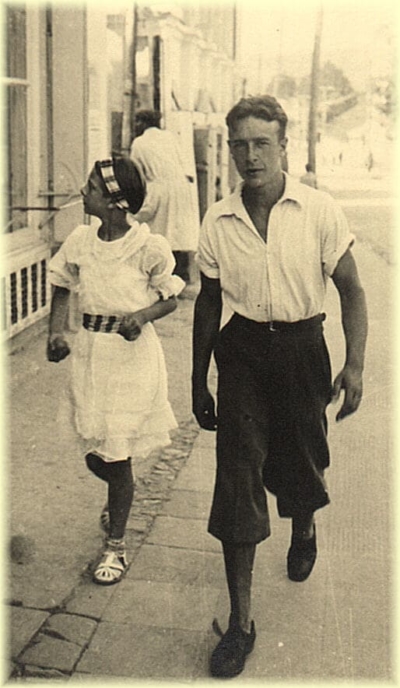

Jan and Natalia

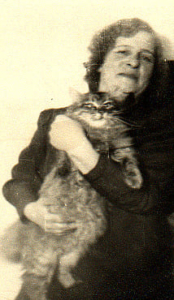

Wanda Sulkowska

About Natalia and Wanda

Natalia was born in Kiev, Russia in 1884, to Benigna and Teodor Timofiejew, Professor of Philosophy at Kiev University. Teodor was killed in Russia (probably by bandits) when Natalia was an infant, and her mother remarried Adam Urbanski, an engineer, who perished during the Russian Revolution. Natalia had three half-sisters by the second marriage: Irma, Stefania and Lusia. She completed Grammar-School with entitlement as a school teacher, but never taught. In 1911 Natalia married Jan Sulkowski, and they had three children: Janina (1914), Czeslaw (1917) and Wanda (1925).

The Sulkowski family lived in Russia where Jan was director of a coal mine from 1915 until 1919, when the family escaped the Russian Civil War in a daring train trip to a newly-independent Poland. Between 1920-1925 they made Krakow their home while Jan was director of shipping on the Wisla River, and from 1925-1932 they resided in Torun and Porebe until Jan lost his job with an American-owned factory during the Depression. The family settled in Krzemieniec in south-eastern Poland where Jan became County Secretary.

In 1939 Poland was divided by Stalin and Hitler, and Krzemieniec was occupied by the USSR. Natalia’s husband and eldest daughter were arrested and sent to the Gulag in 1940, as were many other relatives. Natalia and her children, Czeslaw and Wanda, were deported from Poland to Kazakhstan on April 13 1940 in cattle cars that carried thousands of Poles. Wanda had just turned fourteen and started high school when the war broke out. Most of Natalia’s relatives would find themselves in various prisons, lagiers and labour camps under both the Soviets and the Nazis. Half a dozen would perish in various circumstances, including Natalia’s mother and sister.

Natalia supported her family in Siberia in many ways; gardening, trading or selling possessions, sewing, fortune-telling, as well as arranging for packages to be sent from relatives. At the same time her two children toiled at forced labour. Wanda worked at everything from kneading manure for fuel and bricks, as a shepherd and “tractorist’s helper,” to machine operator, and had many adventures in stealing food and fuel. At one point Natalia would be responsible for eight relatives in a mud hut on the steppes, including the elderly and very young. Disease and starvation were never far, and neither were the Soviet authorities who imprisoned or executed people for stealing food, for not working and other “crimes” against the USSR. Her son Czeslaw joined the Polish Army in 1942 following the “amnesty” granted Poles in the USSR, and eventually made it to England via the Middle East.

Natalia worked tirelessly at family reunification, which never quite materialized. Finally in 1946 she was allowed to return to Poland with her daughter Wanda and other relatives. Life in a People’s Poland was difficult and she depended on packages sent by her husband and daughter from India, England and later Canada. She would never again see her husband Jan who died in 1948 in England. In 1957 Natalia was sponsored to Canada where she lived with her son Czeslaw. She died in 1962 and is buried in St, Catharines, Ontario. Wanda resides in Poland with her family and has written numerous articles based on her life in Kazakhstan which she recorded in several notebooks.

About Natalia’s and Wanda’s Letters

Natalia’s correspondence, in the form of some 70 letters and postcards, can be divided into two sections: Kazakhstan (1940-1946), and People’s Poland (1946-1950’s). The majority are between Natalia and her husband Jan and daughter Janina. Wanda often shared her thoughts in the letters, while also keeping extensive notebooks of life in Kazakhstan. Natalia’s descriptions of her family’s arrest and transport to Siberia are particularly graphic and moving, as are the detailed accounts of life in a cruel environment. She even offers advice on what to take when deported. Her overriding concerns were survival and family reunification. Like her husband, she wrote of plans and schemes to achieve it, and like him, she despaired at their failure. Her letters are often coloured by resignation and despair: “We’re living in a time of wandering nations–we seek where it’s better but always end up where it’s worse.”

Natalia was a believer in tarot cards and fortune-telling, and often described her dreams. In 1947 she wrote of establishing “mental contact over great distances during the time of atom bombs.” She also considered herself an authority in medical matters and gave reports of her ailments, while dispensing medical advice. Natalia also had an authoritative streak (which helped her family to survive) and was not afraid to criticize others. Her letters, and the notebooks of Wanda, are a fascinating chronicle of a family’s struggle against an inhuman system that claimed millions of victims–and a testament to their victory over that system.

In one of her first letters back to Poland, Natalia describes her family’s arrest and deportation to Kazakhstan on a trip of two weeks under such brutal conditions that the NKVD officer in charge, who expressed sadness over Polish children, committed suicide under a train upon arrival.

1940

Stary Suchotin

Krasnojarsk Region, USSR

I suffered very greatly through the moment of our deportation, I didn’t think one could feel that way, shoved down to the bottom of some chasm, trampled, cast out beyond the law. And so it turned out that way, no one was there to say good bye, no one saw us off, I had no chance to buy anything for the trip, only that which was at home, no butter or bread, nor any meats, just the remains of raw ham, slonina [pork fat] and bread. Czeslaw, still after his sickness, completely lost his strength and lay for the whole journey. And now his work is not going well, skinny and miserable he herds oxen, and for his higher studies he dug ditches.

On the day of our deportation, I didn’t have a head for anything; during the night I didn’t want to frighten you by sending the militiaman and putting you in danger. So much suffering–only with the rest of my remaining nerves did I manage to keep myself from screaming in a wild voice and collapsing on the floor without strength and breath. For this reason I simply didn’t want to see anyone familiar, and in the train I didn’t even approach the windows. I was very sorry that I had put Bronia in danger with that wild running around, but we had a sick woman in the wagons[1] and many children and women were asking for naphtha for the primus stove–I would have preferred to have a talk with Bronia in those last minutes.

In such a state of shock, I lost my head about packing things, I didn’t know what to take nor did the children[2]. Czeslaw immediately announced he could only take what he could carry as he had no strength, and I took only one aluminium pot and no plates at all. The first few days in the wagon I didn’t lay down, I couldn’t sleep, I just continuously argued with those who were at home during the packing, and to this day I can’t shake myself from feeling I’m still in my home among all my junk, but everyone suffers through this as they discover. We have no relatives nearby, they’re scattered for a distance of 4.5 kilometres to 150 kilometres. Mama[3] is close to us by local standards, but permits for visiting can’t be had. We’re homesick and eager for news.

Kisses, Nata

[1] The deportation train sat for two days in Krzemieniec in freezing weather.

[2] The NKVD granted half an hour for deported families to pack belongings.

[3] Natalia’s mother and relatives were deported from other parts of Poland.

[4] Natalia sold or pawned items in 1939 under Soviet occupation.

[5] Jan her husband, and Janina her daughter, both arrested and in Soviet prisons.

[6] Zbigniew, husband of Lusia Madalinska, Natalia’s sister, was a Polish officer in a Nazi Oflag.

[7] The two Jewish “witnesses” whose “testimony” helped convict Jan and send him to the camps.

Reply of Natalia’s neighbour, a Jewish tailor, whom she was forced at gunpoint to pick as “caretaker” of her house and property, and whom Wanda begged to take care of her cat Zbik [Wildcat]. Barazcin did send some money to Natalia in Kazakhstan–but both Zbik and most of their property “ran away.”

June 23, 1940

Abraham Baraczin,

Krzemieniec, Poland

Natalia Sulkowska

Kazakhstan, USSR

Highly Esteemed Citizeness Sulkowskaja,

I have received your letter and a postcard. I did not write you back only because I had to work a lot and it is hard for me to get used to it. Coming back to the matters of your letter, your wish to take your belongings for storage notwithstanding, I am unable to give them to you since they have been sold at a public auction. If I were to buy them, it would have cost me a lot of unpleasantness and I would have been under the suspicion that I am appropriating your belongings for myself since the papers did not empower me to do so, as you conveyed this wish to me verbally.

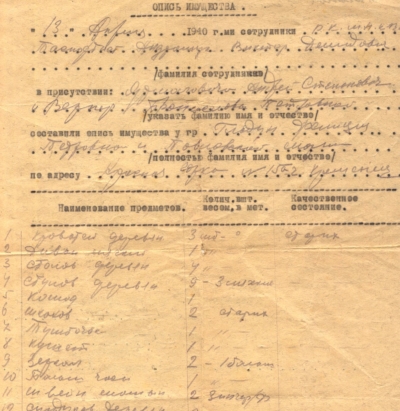

Receipt issued to Natalia for items pawned under Soviet occupation, January 1, 1940.

Zbik: Wanda’s beloved cat with Natalia.

I have already had a great deal of trouble for I tried to buy your belongings for a decent price whereas the other buyers wanted them for next to nothing, and besides there were many such auctions, much more than there were buyers. Many items were not even mentioned on the list, yet they too have been auctioned off. I have sent you all proceeds from the auction through the NKVD in 1939; in regards to flowers, albums and other small items of no intrinsic value to strangers, I was unable to save them, as they too were all taken. There was very little I could do by myself, since Kravchenko, Ivkovskii and others, for understandable reasons, categorically refused to help me at all. I admit that I was very nervous, seeing my own helplessness and the amount of trouble I was already in, not knowing why.

So that you may have a better idea where the sum of money sent to you from 1939[4] came from, I will tell you that the excellent suits and the furnishings from the three bedroom house were selling for 600, 700 and 1000 rubles. Please, convey my greetings to the Baladans and to whole of your family.

Respectfully Yours, A. Barachin.

P.S. I put in a word for Zbik and conveyed him to friends, yet he ran away from them and I do not know what happened to him. In the next letter I will send you a list of sold items and the bill.

Natalia describes the difficult conditions of life on the steppes to her aunt in Poland, including an attempt to set up a garden at her mud hut which she purchased for her husband’s suit (who remains in Krzemieniec jail). She hopes to have him freed, and writes to Krzemieniec, but with no response.

July 14, 1940

Stary Suchotin

Krasnojarsk Region, USSR

Felicia Malinowska

Krzemieniec, Poland

Beloved Fela,

Somehow you’re forgetting about us, you’re not answering our letters and not sending packages (as Wanda is whispering to me). She’s simply sick from hoping to receeive something from you. She was sick with malaria and during her fever she dreamed that she had already received sugar and candies, which so drained me that I decided to send money with a request to buy something and send it to us. Perhaps it’s too hard for you to do this; so much time passes between sending and receiving an answer that it’s hard to become oriented as to what is real at any particular time.

The mud and manure hut in Kazakhstan, bought by Natalia for a suit.

I’ve haven’t yet seen Mama. The children’s continuing sickness, my walking to town and selling some of my goods there, buying the hut here to have a roof over our heads, all these things make it difficult to get away from this place. Taking into consideration the local situation, I’m in the same social setting as I was previously back in Krzemieniec! Namely I have my own house and we still have enough possessions that they might just murder us. They already tried to break in, but the woman living with us screamed so much that the robber will surely not forget this adventure to the end of his life, and what’s more he might even abandon his profession and lock himself away for life!

The Sulkowski Home in Krzemieniec.

It’s hard to get used to this climate, and we’re getting sick. Even so I figure I’ve done quite a bit: namely I didn’t spend all our money on food, but bought a hut, and enough flour for bread till the New Year, potatoes, grain. I seeded our garden with potatoes, some cabbage, a few tomato plants, but it’s doubtful if anything will come of it as vegetables are only painstakingly cultivated here–the whole garden is fenced in by sticks to protect against winds, chickens and children. Such a fence is very costly as there are no forests, and one birch branch costs a ruble as does a bundle of sticks. We planted near our home and around it we put up a few pickets so that a horse or cow wouldn’t get in, but still they sometimes get in. If it grows then that’s good, if not, then just as well.

Did you receive any letter from Irene? I wrote to her but haven’t received an answer about the “Jans”[5] Somehow nobody can manage to find anything out; I try to do whatever I can, but at such a great distance it’s hard.

My things were all sold, so that nothing is left, not even from what I gave for safekeeping. As well my personal photographs–they grabbed them up for free as an addition to items that they bought already at half-price. I didn’t take with me a single photo album. I just don’t understand for what reason anybody would need them! Dear Fela I beg you some day to find a free moment to go to the keeper of my things who was selling them, and maybe he’ll be kind enough to tell you from whom I might get some of my photos back, and while you’re there please look around his place to see what remains of my things.

Kisses, N. Sulkowska

[5] Jan her husband, and Janina her daughter, both arrested and in Soviet prisons.

Natalia agonizes over her losses, and is desperate for word about her husband and eldest daughter who are still in the hands of the NKVD. She even plans on writing to Stalin in this matter. Natalia also make requests for religious items which are of value among the locals in Kazakhstan where religion is banned.

October 6, 1940

Stary Suchotin

Krasnojarsk Region, USSR

Beloved Fela!

I thank you very much for all the news. There’s nothing joyful there; but I’m not burning to return (I’m in the same situation here, the same poverty). Under these conditions we have to wait, and I can wait through it here more calmly. Sadness grows with the approaching winter. Like bees we’re filling all the holes and doors in our hut as winter is starting early this year.

NKVD “Receipt” for property stolen or sold at low prices to the Soviets and their collaborators.

Thank you for your inquiries; it’s too bad about the loss of many things but I also didn’t know what they were going to do with my things nor generally how this is handled. Mama said they didn’t let her take any photographs, they even took them out of the frames and piled them up for burning. I knew that the Jews had been of service to us in this, so I preferred a Jew to be a witness in this affair, and in the future this will be easier in the completion of certain formalities, and in any case I can’t reverse it; nobody would be able to sell the rest of our junk in such times for such a sum. Basinska only got 600 rubles for her entire beautiful household furnishings.

Nothing else but only to survive and somehow to ease the suffering of our poor wretches. For some reason I was so sure that they would release Janek. If someone would try to see what’s going on, to make an inquiry, or to write. I’m writing to Janek, and before I was sending him money and postal money orders of several pages, but if they made it I don’t know. I will be writing about Janek to the procurator and to Stalin–maybe something can be done to ease his suffering.

The worst rumours that plague us here are about our return, about transporting us to a different place, to America and so on. This kind of talk always irritates me, no doubt you’re hearing it too as it makes the rounds. They’re also saying that on the 22nd of this month, on the anniversary of the Constitution, there’s to be an amnesty for all of us bringing freedom. But where could we possibly go to especially in this winter if we no longer own a single thing in the world except for our little corner? Where could we find shelter when everything now is like on a volcano that at any moment will shake, and everything will collapse! One consolation we have so far is that the English and French have it a lot worse, even worse than we had it last year.

As to what other things we still need: some religious medals and crosses if possible. Also beads, a couple of candles for the Christmas tree, church candles and those for the dying. I’d prefer to get the following from you Auntie: beads and coloured blotting-paper to make flowers.

Fela, you’re not writing anything about family and home matters. Do any of you have any news from Warsaw? Maybe you can use the address of the Red Cross: Red Cross Information Bureau, 20 Red Cross Street. To contact the International Red Cross, or the Committee of the International Red Cross, Geneva, Switzerland, you have to write the address in French on one side of the envelope and in Russian on the other. Lusia sent me this address asking me to write about her husband whom she knows is making efforts to get her back to Warsaw where the rest of his family and sister are, but she’s not receiving any letters directly from him as he’s afraid of putting her in danger.[6]

I still would like to find out the details about Janek’s case; with certainty the little Jews know something or other out of curiosity. I want to write to a few of these friends but I don’t have the addresses and I’d like a card in answer. There’s Sarwic’s store of tobacco and sugar near Plutaja, then the tailor Dajszlegiar near the fire station and please make bows to old Stepanieniec.

Hearty Kisses,

Nata

P.S. Snow fell in the night and it seems like it’s already Christmas. They took a couple of boys from here (I’m happy that Czeslaw is still with us).

Natalia complains of postal deliveries and theft of items from packages sent from Poland, and describes a prophetic dream. She continues to agonize over the silence from those in Krzemieniec who were involved in her husband’s and daughter’s arrests (both of whom have since been deported to the Gulag.)

November 08, 1940

Staryj Suchotin

Krasnojarsk Region, USSR

My Beloved!

Thank you for the package, it arrived very quickly and was here at our local post office on the 30th, but our postmistress only gave out the notice on the 4th or 5th near the holidays. Czeslaw wasted time walking to the office. He finally picked it up on the 6th. Czeslaw is still after his sickness, he’s very weak and somehow always feverish. He told us that he waited two hours in the line at the post office where a lot of people were receiving packages. On picking it up, he didn’t reflect on the fact that the package was damaged. There are a lot of mice in that post office; many packages have holes in them, and usually pastry and candies are missing–they eat them.

About sending packages it’s a strange thing that the Jews receive packages very regularly. The daughter of Bakimer gets Polish white flour, honey, rice, and sugar every week, and some of the packages are from Krzemieniec. She confessed that if you have the right connections and can pay well, it’ll be done. I thank you very much for the sent package; I know that it cost you, a lot of work, fussing. Czeslaw begs for twine.

I want good news and some real and fuller news about the two “Jan’s.” I worry myself sick about them. I can’t get anything done without any of those involved; if at least I could find out who those other two witnesses were, the Jews.[7]

What’s new with all of you? Recently I dreamt I was at home with you: Mama was lying on the bed surrounded by kids, Ludmilka was frolicking on the floor and Zygmunt was sitting at the desk and writing. There were apples laying on the table, fresh apples, and some boxes, and I was saying that undoubtedly you’re preparing a package for us. The next day there was a notice for us about a package! And so there is some kind of mystic connection, even at such great distance.

Kisses for you,

N. Sulkowska

[7] The two Jewish “witnesses” whose “testimony” helped convict Jan and send him to the camps.

Natalia complains of postal deliveries and theft of items from packages sent from Poland, and describes a prophetic dream. She continues to agonize over the silence from those in Krzemieniec who were involved in her husband’s and daughter’s arrests (both of whom have since been deported to the Gulag.)

November 08, 1940

Staryj Suchotin

Krasnojarsk Region, USSR

My Beloved!

Thank you for the package, it arrived very quickly and was here at our local post office on the 30th, but our postmistress only gave out the notice on the 4th or 5th near the holidays. Czeslaw wasted time walking to the office. He finally picked it up on the 6th. Czeslaw is still after his sickness, he’s very weak and somehow always feverish. He told us that he waited two hours in the line at the post office where a lot of people were receiving packages. On picking it up, he didn’t reflect on the fact that the package was damaged. There are a lot of mice in that post office; many packages have holes in them, and usually pastry and candies are missing–they eat them.

About sending packages it’s a strange thing that the Jews receive packages very regularly. The daughter of Bakimer gets Polish white flour, honey, rice, and sugar every week, and some of the packages are from Krzemieniec. She confessed that if you have the right connections and can pay well, it’ll be done. I thank you very much for the sent package; I know that it cost you, a lot of work, fussing. Czeslaw begs for twine.

I want good news and some real and fuller news about the two “Jan’s.” I worry myself sick about them. I can’t get anything done without any of those involved; if at least I could find out who those other two witnesses were, the Jews.[7]

What’s new with all of you? Recently I dreamt I was at home with you: Mama was lying on the bed surrounded by kids, Ludmilka was frolicking on the floor and Zygmunt was sitting at the desk and writing. There were apples laying on the table, fresh apples, and some boxes, and I was saying that undoubtedly you’re preparing a package for us. The next day there was a notice for us about a package! And so there is some kind of mystic connection, even at such great distance.

Kisses for you,

N. Sulkowska

[7] The two Jewish “witnesses” whose “testimony” helped convict Jan and send him to the camps

The first Christmas in the USSR was very difficult for Natalia and her children. Yet they managed to maintain Polish traditions, even as they wept over the fate of their family. Natalia lists a litany of hardships they must endure, such as the climate, starvation, and disease (which almost claims her son Czeslaw)…and still has no word about her husband and daughter. She also scolds her neighbours.

February 01, 1941

Stary Suchotin

Krasnojarsk Region, USSR

Beloved Auntie!

This first Christmas without our closest friends gathered around the Christmas tree singing carols, was very sad. There was no Christmas tree. Wanda and I boiled some borscht and I even made little uszka [dumplings].We had a few dried mushrooms with onions, there was kutia,[grain dish] compote, and pierogi with sauerkraut and oil. Czeslaw got a real sunflower from a German at the market–cooked it was very delicious. We were making pierogi with potatoes from noon, enough for us for two days, so that I didn’t even cook any meat as I was planning. We had no dishes left, but then we saved fuel and food as well, so that the whole holidays were meatless.

Wanda and Czeslaw in Kazakhstan with an engineer deported from Moscow.

We had Wigilia early at 7 or 8 and went to Mrs Slowinska’s, who had been transported from Hladek. Mr and Mrs Zolyniak also live there with their three sons and her old mother. They hadn’t yet sat down to the evening meal and were singing carols; Czeslaw sang the most, but the hostess made it difficult with her horrid squeaking! The Zolyniak children made themselves a Christmas tree from a buran, a local ball-like plant which grows up to a metre in diameter and which the wind blows from great distances. The boys hung the tree with sugar wrapped in paper and had a great time. Zolyniak was an office worker with the police in Krzemieniec, but I didn’t know the family. Wanda knew one of the boys from school, and I only met them here.

The Basinscy (from Krzemieniec) live in Karolina which is some 40 kilometres from us. She left a few things with me to sell as they are far from the town. They’re also as poor as church mice, and live in poverty with Radiszewska. All because they’re good-for-nothings! The boys are wild and lazy, while she is a great “Lady” who can’t even patch or darn. That Jurek shows up dressed in rags so that it’s embarrassing.

Wanda and Czeslaw in happier times, Poland.

Everything suddenly ran out for us; all our supplies, things and money. Everything became cheap in the market: flour which was up to 200 rubles for one box, is now going for 80 rubles a box. It’s becoming more difficult in getting paid from work. They’re just paying Czeslaw and Wandzia now; together they received 6 kilograms of pork and will get something else or other, and that’s it. You can’t live or die on that! That’s not counting clothes and shoes. The air here is so sharp that everything simply burns up–in the summer the sun beats down and the winds blow, and all this affects the clothing like chlorine. I simply can’t imagine what will be. We have to keep working in the kolkhoz as they won’t give us a garden, and if our clothes finally fall off us, they still won’t give us new clothing and we won’t be able to buy them as we can’t earn any money and so it all goes nowhere.

Mama writes often. She survived the most severe frosts; it was very cold there and many homes only have single pane windows as they do here. The children survive the cold very well and not one of them was sick. Mama cheers us up that we only have to make it though February, and if we survive it then we’ll somehow keep living. But I’m terribly worried about Janek and Janka–how are they enduring? I just can’t find out where they are, but I’m afraid of creating too much bother which could be hurtful.

Here we burn kisiak, made from straw and manure. It’s the kind of fuel that you can never calculate how much you’ll use, and everybody is short of fuel. This is to the advantage of those who live in areas where scrub brush grows and which they now sell for 3 rubles a bundle. Czeslaw was going out scything srcone, and scythed a wagon-load for himself and for a blind man who supplied horses for transportation. Later he set out on the steppes to scythe wormwood for others who paid in flour: one box of flour and accommodation, for one wagon of wormwood. But he returned from this expedition very sick–most likely typhoid fever. I couldn’t call a doctor but somehow we got through it. How Wanda and I suffered nightly at his bedside and how I worried. But it seems such is my miserable loss to worry my whole life, and truthfully at present there’s not a little to worry about.

From Jurek Basinski we learned of the death of Turkiewicz and about the sickness of Sanojcuwna, and from the girlfriends and boyfriends of Czeslaw and Wanda we know all about the matches and marriages of their snooty-nosed friends back home. It’s the same here where they make sure that as soon as anyone arrives from the army, that they should get married above all. From Musia I received a letter in which she reports that in Warsaw all her friends and relatives are alive and in good health. With the help of Janka’s friends she found Lilka’s Zurawska’s things which had been abandoned by Janka. Kalina is still sending me her greetings (your upstairs neighbour) and asks if Basinska is alive. Somebody told her that Basinska had died and that her children were with their uncle, God forbid! There are so many political rumours circulating that it’s not surprising that they tell all sort of stories about us: that many of us are dying, that many froze to death in blizzards coming with packages and money from the post office. Czeslaw didn’t meet such conditions.

Kisses For You,

Nata

This Christmas card was created by Czeslaw who scratched the picture on photographic paper and exposed it carefully. It shows the the Star of Bethlehem over their mud and manure hut and was sent to relatives in Poland–escaping Soviet censors who perhaps saw it as a Soviet star.

“The best wishes for a Happy New Year are sent by the inhabitants of this little house, Dec. 19, 1940.”

Natalia offers practical advice on what to bring to Kazakhstan to relatives in Poland who are in fear of being deported. She also throws herself into various jobs and schemes to maintain her family, even illegal ones such as sewing on the side and dealing in religious items.

1941

Stary Suchotin

Krasnojarsk Region, USSR

Deportation: Victims were usually given half an hour to pack for Siberia.

You are all asking for details about what is most needed here; quite simply one should only have a few things, but really necessary ones–often in haste many different things are taken. Very few people had time to grab something useful, and amazingly nobody has any dishes or even cups for water. Of kitchen utensils you’ll need 2-3 pans, a frying pan, a measuring spoon, and a bowl for washing, preferably large so that you can also use it for laundry. People brought wash tubs, washing machines, cauldrons for cooking–a necessity, but with the lack of fuel it’s not used, and it’s just not worth the trouble. Better to have more clothes: sheets of Wolyn cloth, pillow cases, coloured bed lining, blankets, sheepskins, warm shirts and hats, gloves, felt boots, galoshes or else good snow boots, woollen stockings, socks, warm kerchiefs–all those things that I didn’t take!

I can still earn a little this and that with my sewing, but I have to do it extremely carefully as I have to pay tax. All the tailors sew on the hush; you go in the employ of some protector at the army base, you sew slowly but charge a lot for your work: 2 boxes of flour for a set of clothes. Buczek, who had sewn for the regiment in Bialokrynica, now sews in homes and earns 20 rubles a day with accommodations. The higher office workers use his services, but he won’t be earning that for long; Buczek’s wife sews in the Artela (Association of Workers) and earns some 260 rubles but this is very little. I am a first-rate seamstress here. Sewing makes it a lot easier for me to get goods. I sew men’s jackets with great success; just now I had to finish an order for two silk dresses, a jacket and a blouse.

Please ask Mrs Kraszewska, with kisses and bows from me (I’ll also write to her) for an old magazine and a couple of patterns of the most fashionable style of flaring skirts, and for the sleeves of some shapely dress that’s easy to arrange for Soviet taste, with directions. I couldn’t write as I still don’t have a sewing machine and have to walk a great distance to friends to use theirs, and I also have to sew a lot by hand which could by done by machine.

I need needles for the machine, about 4 regular ones, a couple of neck chains for medallions, some small broaches, coral beads, and more medallions, for which I thank you, as they are greatly valued by the Russians. The women thanked me with prayers for the scapulars which are very good–I cried reading them. The women ask me for scapulars and religious pictures.

I have a request regarding the package, about the mail C.O.D. costs; that is I will for the shipment which is quite expensive at up to 20 zloty for 8 kilograms, but it’s only worthwhile for me if there will be included some sugar, tobacco and hops on yeast which are valuable here. The duty for this will not be too much trouble.

Heartfelt kisses for everyone,

Nata

One of Natalia’s first contacts with her husband who was in Starobielsk prison in the USSR (through which daughter Janka also passed–and which had housed 3,900 Polish officers who were secretly executed in 1940 by the Soviets.)

March 1941

Kazachstanskaja OBL. Krasnoarmiejsk

Nowy Suchotin, Stary Suchotin

Sulkowskiego Jana Waclaowicza

Starobielsk Woroszylowskaja oblasti

Skrzanka Nr.15I

I send you greetings!

We’re all alive and healthy, and wish you the same. I received a letter from Bronia Malinowska who received your address from the doctor. They’re settled down and would like to send you a package. Your suit is there with them but it’s not good for work. At home here it’s completely good–we walk 7 kms to the market…[illegible].

Receipt for the sale of the hut Natalia had purchased the previous year for her husband’s suit. The family moves into one room in a barracks where Wanda and Czeslaw work at a grain elevator.

June8, 1941

Sold: Sulkowska Bought: Martynowicz

Natalia has finally established contact with her husband who was freed from the Gulag as a result of the “amnesty” given Poles to form a Polish Army to fight the Germans. He is recovering in a Soviet hospital, but there is no word from their daughter (who was released at a later date from a labour camp). Natalia throws herself into the difficult task of getting her and her relatives into the protection of the Polish authorities–a route filled with Soviet roadblocks. But plans to escape southward will not materialize.

June 30, 1942

Stary Suchotin

Krasnojarsk Region, USSR

Jan Sulkowski

Invalid’s Home

Bukhara, USSR

Beloved Janek!

NKVD Senior Officer: Without a permit from them, Natalia couldn’t travel, move or change jobs.

Yesterday I received your letter written on the 13th, and I’m simply delirious. It’s difficult to even gather my thoughts! It’s important to get ourselves out of here. I’m so frightened by certain misfortunes, by the hostility to us and the adversarial stance of the powers that are. Only those families are leaving who somebody comes to take out. It’s easier to depart from other places, especially from Achmolensk Oblast. I constantly regret that we didn’t leave last year at the time the Stadniczy were going.

I can’t think about anything, I can’t do anything–only that I have to get myself out at any cost. When we’ll be together, only then in steps will I able to tell you what we lived through. I have to find myself in a different environment, different circumstances–to be working among my own.

I’ve cried myself out with so many tears for Janka, and finally I would just like to know the truth about what has happened to her. If she was at all alive she would have answered us by now, especially as she knew my address. If she had been writing, then at least something would have reached us. Your letters reach me, but my letters don’t get to you–for sure there is a deliberate and terrifying purpose in this.

Wandeczka and Kocia have to go to work in the fields under the threat of deportation to Karaganda, the hardest prison. At home we also do work for ourselves, too hard for Wanda’s age: carrying water from a distant well, transporting wood from the forest, making fuel, and working among people for potatoes and food. This is my project for getting us out of here. If there is an invalid’s home for women where you are, then submit an application for Mama and Stefa, and also for old Wolk. Kocia is still wavering, but she herself should have put in an application a long time ago as she is a Sergeant in the Women’s Squad. I told her many times but she apparently prefers to have Wanda and Adas under her command here; she’s a businessman like I am and always has a fair amount of goods. Babcia is also selling the rest of her things and still has quite a lot.

We registered the children for transport; I could have registered Wanda as well, but first I would like join you. Probably delegates will be sent for the children. So maybe we could get Adas and Krzys admittance to the orphanage in Bukhara, plus admitting Babcia and Stefa to the invalid’s home there. Maybe they could delegate you to that transport? More children will be leaving here as a lot signed up. I’ll travel to Pietropawlosk where there is a secretary with the Polish Delegature, Koszinska from Krzemieniec, who advised me by telephone that you should get a permit from the NKVD to sponsor your family. Send me the papers and then without any barriers I’ll proceed.

Kisses,

Nata and Wanda

Siberian Graves: Adas made crosses from pieces of wood.

Natalia chronicles her life in Kazakhstan, while still planning family reunification–hoping now that Jan and Janka can come and join her. But in just a few weeks, her husband and daughter will go to Persia.

July 3, 1942

st. Smironowo, poc Poltawka

Kijaly, Kazakhstan, USSR

Jan Sulkowski

Invalid’s Home

Bukhara, USSR

Beloved Janek!

I owe you an account of all our time, of our life in Kazkhstan. I bought a hut in June of 1940. We planted a potato garden. I set up hens and ducks–in a word only a cow was lacking for paradise on earth! We did all this for you and Janka, that you should have a place to rest after you arrived, somewhere to lay your heads and call home. We all worked together for this. Czeslaw applied himself to different jobs; he quickly got sick of kolkhoz work, discouraged that they didn’t pay. He looked for something better-paying; he worked in a salt mine, later for people at scything wormwood and other crops for fuel, and the like.

Czeslaw was sick through the whole winter until April. In March there was a time that I thought he wouldn’t make it. I drove him to the hospital but they couldn’t do anything for him. Hating hospitals, and not wanting to worsen his disease there, he escaped home and started recuperating from his stay. He was nursed back to health by a Polish neighbour, Kozakowska, who had been deported here along with others back in 1936 from the USSR. At the end of April he started work on building a grain elevator and was happy with the ability to buy bread for himself and his family, and we were plenty hungry. It was touch and go with flour, also there was a shortage of fuel due a flood and all manner of natural disasters that always entertain and enliven our daily life.

Jan and Janka on their way to India, 1943

In June everybody was transported to work in Achmolensk; Czeslaw was already on the way, but luckily he was left working at the elevator. I sold our hut to the Tarnowskis from Krzemieniec, two older people unsuited for work. He bartered it from me for a song, and we moved into the barracks–a usual fact of life for local workers. Czeslaw would be at work the whole day, I would feed him the best we could but he would have to stay till night with only dry bread. He had to walk about 20 kilometres to work through fields and steppes. He would return so exhausted that he would eat half-asleep usually in bed. This was killing him so that for his own good we had to move.

I received your letters from Turinsk and I telegraphed you about a position for an accountant. We went to the railway station to meet every train, and I wrote many times–all without results. The building of the elevator was completed and Czeslaw was transferred to Kijal as an electrician while Wanda and I remained in place. They gave us a lot of problems but later allowed us to move to Kijal. But they threw Czeslaw out, and sent him to Omsk to a third elevator, where they paid him poorly. I advised him to quit, and I absolutely decided to head south to find you at any cost. We sold most of our things, but many still remained, so I decided to leave most of them for Mama, and thus we came to Poltawka.

Czeslaw earned what he could by working the whole month at digging out wheat from under the snow; he brought us two boxes of wheat but couldn’t bring more due to the distance. On February 7, 1942, he set off for the Polish Army. He took along a bunch of postcards which he was to mail to you along the way We had your address and received two of your postcards. I telegraphed a few times and wrote to different institutions and to our Delegates. Only now did a telegram suddenly arrive, a mixed-up one naturally. Wandeczka and I walked 28 kilometres to Smirnowa where by telephone I talked with Kosinska who works as a secretary in the Delegature. She also told me that I was allowed to travel to you on the basis of your call to the Polish Army. You must try to get a travel permit for me and Wanda from the NKVD. We’re waiting for Lusia and Czeslaw to get us out; apparently they thought it was enough that we were added to the list of army families. So far only those are leaving for whom special delegates are sent, or who receive papers for free travel and accommodation. Money I have too much, and you’ll see I can always earn more for tobacco for you and extra food for all of us. If only finally we could all be reunited, I would immediately buy you a couple of kilos of tobacco.

Kisses,

Nata

Natalia and Wanda have moved into a small hut with relatives–eight in total, including the elderly, sick and young. She turns to fortune telling to help feed them. Wanda is the only one working as Czeslaw joined the Polish Army in February and has left the USSR. Janka and Jan were reunited in Bukhara.

July 15, 1942

st. Smironowo poc. Poltawka

Kijaly, Kazakhstan, USSR

Jan Sulkowski

Invalid’s Home

Bukhara, USSR

My Beloved!

Workers of the Tractor Factory: Wanda (back row, right) with exiles from many lands, Kazakhstan, 1945.

My nerves are terribly exhausted by this waiting, this uncertainty, and especially by our living conditions. Since November I’ve been with Mama in a complement that includes old Mrs Wolk, Stefa, Kocia, Adas and Chris. Stach and Irma and the girls have remained in the country. First of all it’s too expensive for us to co-habitat with boarders of an invalid’s home! It’s high time for us to disentangle ourselves; this winter they were all living at my expense, and they consider it normal that the two of us always have to share with the six of them. That which lasted us for four days, suddenly turns into hunger. I’m helping everybody else, yet somehow I can’t advise myself how to leave here quicker.

I have constantly supplanted my income by sewing, but it is my occult talents that open the most doors and hearts before me. I cast horoscopes splendidly and am getting constantly better–I’m already famous here and beyond our borders! I have decided to never part with this to the end of my life, and to actually perfect my skills. I’ve decided to study hidden knowledge in India with yogis. Are there some mysterious astrologers in Bukhara? You simply must find out for me.

Czeslaw in the Polish Army (right) Persia, 1943, on the way to England and the RAF.

The climate is ill-suited for Wandeczka, she’s constantly sick with a sore throat…her tonsils will have to be removed. All it takes is that she gets her feet wet, a gust of wind, and instantly her bones hurt, her teeth and kidneys ache, her ears get dizzy. Last year she was doing much too hard work at construction, and damaged her heart, or rather her heart condition got worse. It’s impossible not to get your feet wet; you have to knead the manure with your feet–and Wanda cut her feet so badly that they were peeling! Luckily we don’t hear of any more accidents involving the heart as there wouldn’t be any help in trying to save Wanda. This climate has all the worst: heat waves and polar cold, but there are no cobras or scorpions. However there are tarantulas and huge spiders.

Since February, Czeslaw has been in the army; the last news I received from him was from Krasnovodsk just before the steamship departed across the border. He wrote that he thinks we’ll follow his trail. There’s a letter from Lusia from Teheran where she also went as a volunteer. She has hopes of taking us in.

Dear Janek, only our reunification will help our material circumstances. Since November I’ve been trying to feed six people here, but I would prefer to feed (other than Wanda and myself) just one person–You! Every litre of milk I divide into eight portions. I’ll try to endure this time of waiting to travel by somewhat gathering my strength as I too am miserable, skinny as Indian death.

Kisses,

We await news, Nata and Wanda

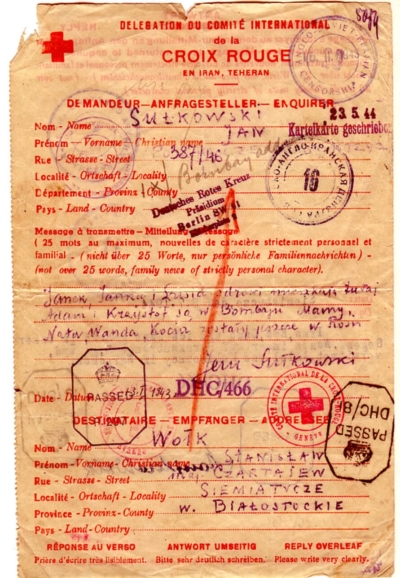

A Red Cross enquiry from Jan Sulkowski

This postcard written in Russian by Natalia to her sister in the Polish Army in Persia, is one of the last items of correspondence until after the war’s end. The Nazi invasion and occupation of the USSR disrupted communications save for the Red Cross. Natalia and Wanda must remain in the USSR.

December 2, 1943

st. Smirnowo, poc. Poltawka

Kijaly, Kazakhstan, USSR

Lusia Madalinska

Polish Red Cross

Teheran, Persia

Dear Little Sister!

I bring news that we’re healthy.

Our Mama is still holding on not that badly, as are the rest of us. I’m very grateful to you for your shipment, which I received. Our Mum cried like a child. I was very moved as well. You see how terribly I long for my close ones.

Are you corresponding with Czeslaw, Janka and Jan? Give them a kiss from me. Wandeczka is leaving for a veterinary attendant’s course; somehow it’ll work out but please remember us.

Kisses,

Nata

Adam Wolk was deported to Kazakhstan at age eleven with his brother Krzys who was three, along with four female relatives, two of them elderly and one mentally sick. They were transported 80 kilometres from Natalia, and would later share a home–eight people in a mud hut. “Adas” and Wanda shared many adventures in Siberia. “Granny” was Benigna Urbanska, Natalia’s mother. Adas and Krzys returned to Poland in 1946 with Natalia and Wanda–leaving many graves behind.

1945

Kazakhstan, USSRStefcia was crippled and couldn’t sit up anymore. She began to talk less and less. Granny and I gave her some sugar. She licked it and smiled and died peacefully. Some men were hired to dig the grave. They dug it for two days even though there was four of them. A Chinaman, a Korean, and two Poles who did it for free. They gave us a horse from the kolkhoz, but there weren’t boards for a coffin. We wrapped Stefcia in her favorite green blanket.

Babunia died next in February. She was blind and over eighty years old when taken in the transports. She had not left our hut for almost a year. She had terrible bedsores. For a long time she was unconscious. She died in her sleep. We buried her in a blanket too. I made a cross for her.

Granny was busy cooking and selling that summer. At first snowfall she was hit by a big horse-drawn sledge. She too had terrible bedsores. She said that she could only die in peace knowing that I would leave this awful place. One morning she gave a last fling, and seemed to fall sleep. I went to fetch the neigbours in a snowstorm. They washed and dressed Granny, and on the third days was her funeral. There were quite a few Poles. There were no boards for a coffin.

Adas

Natalia, Wanda and surviving relatives were allowed to return to a Communist Poland in 1946–but not to Krzemieniec which was part of Poland annexed outright by the USSR. The Sulkowski family was now divided by the Iron Curtain: Jan, Janina, Czeslaw, and others, were in India, England and elsewhere. Natalia and Wanda would never see Jan again, who would die in England. Wanda who had been denied education at 14, went back to high school as an adult. Here she offers a glimpse into her suffering and the loss of loved ones in the war, skirting deportations and deaths (such as Katyn) at the hands of the Soviets–the mention of which was a “crime” in the new regime.

1946/1947

Biala Podlaska, Poland

Jan and Janina Sulkowska

Bombay, India

Dear Daddykins and Janulka,

Poland’s borders shifted West

Me and Mummy are with Aunt Musia. We all came together with Tunia and the boys. The Wolks regained their sons, but we two are still alone.

I’m preparing myself for High School as I’ve forgotten everything in six years. We long for you and live only for your letters. Ewa brought us your first in a long time and it gave us great joy. The photos have given us hope: Daddy has changed little, but Janka looks miserable. This saddens us.

Our dear Czeslaw helps us a great deal from England. We receive letters with cigarettes and nylons from him. We are still searching for Aunt Jadzia who disappeared in the war. Ewa will search all the hospitals in Lublin.[1]

Why is fate so cruel that it has scattered us around the world and keeps us apart? I’m young and will survive, but Mama needs recuperation–instead she is worrying herself to death and I can’t provide her with the care she deserves. When will we be together again? Even if it is in poverty, it would be the greatest joy possible!

Every day I take a steam bath and use a shower–I do this as much as I can, as they say it’s good to steam out the dirt and bugs which I acquired in Siberia.

Natalia and Wanda

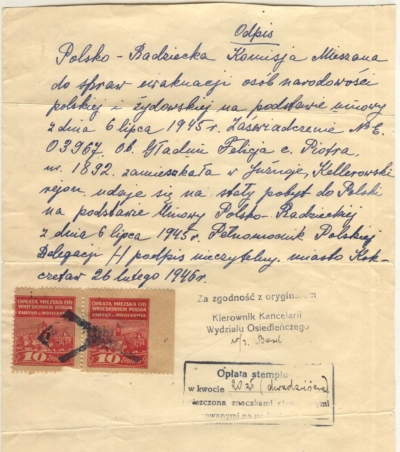

Natalia’s Ticket to Poland in 1946: “The Polish-Soviet Commission for matters of evacuation of people of Polish and Jewish nationalities.”

I have a vow which I made long ago to make a pilgrimage to Czestochowa. I would like to thank God for his mercy, which he showed us during the war and our terrible experiences–and I had many of them. Once I was a hair’s breadth from being thrown into prison, and another time I was robbed on a train and I jumped our after the thief! I bashed my head, but God protected me. Now I don’t meet as many sorrows and am simply happy that we finally escaped that Hell. I’m content and often merry, and I even dance, which I didn’t do before.

I have news about some of our old friends from Krzemieniec. Many of them were killed by the Germans. There were beloved professors Maczak, Opolski, Poniatowski, the lawyer Choculski, and others. The Poplowskis are in Slask but the brother died in the Warsaw Uprising. Rys J. and Jurek S also perished. Zygmunt Rumel died in the Uprising[2] and his wife is in Warsaw. The sister of Roman Oleksyn, drowned. Abouts so many others I don’t know.[3]

It’s so difficult to think that Poles scattered around the world are leaving graves everywhere far from their fatherland–how terrible it must be to die on foreign soil. Our family as well. Granny and Stefa and so many friends in Siberia–oh how hard it is!

Mama constantly talks about Janka coming home and that you’d find work here. Mama says she’ll put out four liters of vodka and we’ll all get drunk. What a great joy it would be if you could come and forget about your past.

With impatience I await that little Indian god that you promised me Janka.

I Kiss You with a Thousand Kisses Over and Over,

Your Wanda

[1] Jadzia Sulkowska, Jan’s sister, had gone to the war front in 1939 as a nurse where she was wounded. The family found her.

[2] Zygmunt, a member of the Polish underground, was actually murdered by Ukrainian nationalists despite assurances of

safe conduct. His body was never found but apparantly he had been tortured and drawn and quartered with horses.

[3] Wanda couldn’t mention those who had perished at the hands of the Soviets, such as Jurek S. (Szmlastych) murdered at Katyn.

[4] Some 3.5 million Germans were removed from parts of Germany given to Poland after the war. Their homes were taken over by 2.2 million Poles returning from German concentration camps and slave labor, and by 1.5 million Poles ousted from areas taken over in Poland by the USSR.

[5] The Soviets stood by and let the Nazis crush the Warsaw Uprising.

[6] Surplus parachute cloth was sent by people from the West to loved ones in Poland where it was sewn into clothes.

Natalia and Wanda were forced to live with relatives in a number of places, and had to cope with many difficulties, including a Communist government which denied them services. They survived with the aid of packages sent from India and England, that Natalia traded on the black market. Natalia describes the harsh conditions in post-war Poland, even as she dreams of family reunification.

1946/1947

Biala Podlaska, Poland

Jan and Janka Sulkowski

Bombay, India

We received your precious letters and are happy beyond measure. We hadn’t been writing from Siberia as we didn’t know if you were still there. We dream about you all the time. Last night I dreamed of you in your old office, and that I was writing in a great book to resolve some question–maybe we’ll be doing some corrections!

We received your precious letters and are happy beyond measure. We hadn’t been writing from Siberia as we didn’t know if you were still there. We dream about you all the time. Last night I dreamed of you in your old office, and that I was writing in a great book to resolve some question–maybe we’ll be doing some corrections!

The Seat of the County is still hidden with me as is your passport–can you use them? It will be important for Janka to have a record of her arrest with a list of what was taken from her, and also her university documents. I have your Radiophonic Registration Card stating your profession as Secretary of Krzemieniec County.

We still don’t have our own little corner, but live temporarily in a home that’s not too bad. I lost the opportunity to get even a small home in the west as I wasn’t allowed to leave Siberia.[4] My rheumatism started bothering me here and my nerves and heart are good for nothing. Wanda is anaemic, her head aches, and now her teeth are rotting. I got very sick with a carbuncle on my neck and was near death for several months–leaving horrid scars on my neck. I couldn’t seek medical help as it’s too costly, and I was refused welfare as my husband is outside the country.

My vocation as a fortune-teller still finds people in this environment who run after sensational promises. I scrape along by doing a little trading, sewing and teaching French. At my 60 years of age, it’s hard to get going as I never had good health. We’re living in a time of wandering nations–we seek where it’s better, but always end up where it’s worse.

Stalinism and postwar chaos will claim 300,000 lives in Poland.

Mama’s end in Siberia came quickly. She was 78 after all. Mama often said: “I only want to live long enough so that I won’t die before Stefa!” And so she hung on to take care of the kids. Adas put a cross on the grave while Wanda planted flowers, and I took some earth and flowers from the grave. Mama’s grave was dug by a Finn, a huge lad who had higher education, but couldn’t cope. He died shortly after.

We left under a shadow of funerals. So many young people died. Mrs Skofnicka, a young woman, died of cancer. She had been kept alive by the thought of bringing her daughter back to Poland. But she just shrivelled up, and didn’t make the voyage home.

Old Buckowiecka won her case for rehabilitation and will be rehabilitating her children. In this neighbourhood, they made everybody into a Volksdeutsch [ethnic German collaborator]. People lived through Hell, and are still living through Hell because of them. They tortured to death Old Buckowiecki by forcing him to dig up bodies murdered by the Nazis. They said his daughter Ela, who escaped to the West, was on intimate terms with the Germans etc.

The fact is that those people who were really at the trough with the Germans, are now screaming new ideals–they’re sending innocent people to jail while they live the good life. They prey on others: if they find someone has hired Germans, they take everything from them and deport the Germans. I learned about many cases of szaber–the looting of people’s possessions during fighting or pillaging abandoned houses.

The fact is that those people who were really at the trough with the Germans, are now screaming new ideals–they’re sending innocent people to jail while they live the good life. They prey on others: if they find someone has hired Germans, they take everything from them and deport the Germans. I learned about many cases of szaber–the looting of people’s possessions during fighting or pillaging abandoned houses.

Uncle Stach is only now coming back to his former self after his stay in the camps and in Ostaskhov. He recently worked as a chairman of the Red Cross, but it paid little and all the responsibilty was on Musia’s shoulders.

Searching for loved ones is not always joyful. And so Janka, your Godfather died in Siberia, but his wife and daughter returned to Bedzin. The Seiferts saw their son murdered before their eyes. I just can’t get around to visiting them–what could I say?

Zygmunt Rumel was killed in Kowel. Julek fell in Warsaw. The Germans had to remove most of their forces while there were Soviet troops on the road–but they retreated. When the Warsaw Uprising began, the Wilanowa Palace was like an armed fortress, but no help came from the forest and all the Poles perished.[5]

Every day I run to the doctor, the magistrate, to stores for rations, on market day to town to sell something. In these post war days, it’s best to grab something, go outside and sell it. There are many professional dealers, men and women, and those like me who are half-professional because we sell our own stuff and squander it quickly on food. I can never manage to get rich in the American style. My trading doesn’t give much, and so we never have meat, at most twice a month, and exist on potatoes. Luckily I learned to be frugal in Siberia.

Wanda and Janka, 1992

As to the streptomycin antibiotic for Krzys–send it quickly before it’s too late! His state is bad and there’s no place for him in a sanitorium for insured patients, and no money for a private clinic. The antibiotic is more valuable than parachute cloth [6] when it comes to trading and is in a price-range that will pay for a two-room house with furniture! Thanks to your penicillin shots, I can now sew on my new sewing machine. But my hands and feet are still scarred from punctures and my thighs hurt so much, that it’s hard to sit. This is the current state–please hurry up with the “shipment,” and bring as much of it when you come instead of other baggage which they’ll take away from you anyway. Also send cards of the fortune-teller Lenormand in French and a dream-book.

You probably picked up the idea of going off to an uninhabited island–if not then I’m beginning to believe in mental contact over great distances. If you and Janka agree, then maybe mind contact can be made at this closer distance, and during the time of atomic bombs!

P.S. Irene tells me about your romances Janka, and how you gave up a Maharajah’s tea plantation–you heroine!

I Kiss You both

Mother Nata and Wanda

[1] Jadzia Sulkowska, Jan’s sister, had gone to the war front in 1939 as a nurse where she was wounded. The family found her.

[2] Zygmunt, a member of the Polish underground, was actually murdered by Ukrainian nationalists despite assurances of

safe conduct. His body was never found but apparantly he had been tortured and drawn and quartered with horses.

[3] Wanda couldn’t mention those who had perished at the hands of the Soviets, such as Jurek S. (Szmlastych) murdered at Katyn.

[4] Some 3.5 million Germans were removed from parts of Germany given to Poland after the war. Their homes were taken over by 2.2 million Poles returning from German concentration camps and slave labor, and by 1.5 million Poles ousted from areas taken over in Poland by the USSR.

[5] The Soviets stood by and let the Nazis crush the Warsaw Uprising.

[6] Surplus parachute cloth was sent by people from the West to loved ones in Poland where it was sewn into clothes.

Christopher Jacek Gladun was born in 1951 and grew up in Canada to where his family emigrated from England as displaced persons. Sadly, Chris died in Toronto in March 2003. He held a diploma in Journalism from the Niagara College and a BA in Polish Language & Literature from the University of Toronto. Chris also acted as interviewer and researcher for the documentary film “Rescued From Death in Siberia”.

This content is now maintained by the Kresy-Siberia Group, which Chris was a charter member of and which is taking his website and his research work forward.