Quick Links

Transit Camps and Centers for Poles in India

In India, in the period from 1942 to 1948, there were several types of Polish refugee centers. These were primarily permanent settlements in Valivade and Balachadi, a treatment center in Panchgani, and convents where young people were educated: in Karachi, Mount Abu, Panchgani, and Bombay. There were also two temporary centers established at the earliest, where Polish children evacuated to the subcontinent by land stayed for a relatively short time – in Bandra and Quetta, and two temporary camps for Poles reaching India by sea – both near the port of Karachi – Country Club and Malir. Poles were sent to the Country Club camp from September 1942. It was located in a valley between two military camps intended for the British (Royal Air Force) and American air forces. On average, the Country Club housed about 2,000 people, with a permanent staff of about 200 employees. The refugees were subject to military discipline, as they were in the camp under the care of the English authorities, who cooperated with the Polish authorities.

The camp was in English-type tents with double roofs adapted to the Indian climate. Several connected tents housed about 50 refugees. Each tent had a different one – a small one, with a washbasin (water was brought to it by Indian camp workers). In these somewhat Spartan conditions, the Polish refugees were provided with blankets, pillows, mosquito nets, buckets and clay pots for drinking water, as well as bedside dishes for children. At a distance of about 150 m from the residential tents there were three bathrooms for women and two for men, each equipped with eight showers placed in separate cabins. Near the bathrooms, by the taps, there were eight basins that the refugees could use. In the same area there were toilets for women and men.

In turn, a school and a hospital were organized in rows of connected tents. The canteen was a wooden structure, open on all sides. Like the hospital and kitchens with dining rooms, it had a cement floor. Lighting throughout the camp was provided by kerosene lamps. There were also laundries with running water, where 20 people could wash their clothes at the same time. A warehouse was located nearby. In the camp there was a canteen and the “Społem” cooperative – a food shop, which brought in income (after the liquidation of the Country Club, the income from the shop was used to buy a printing house in Valivade), and in a separate tent there was a sewing room, which was equipped with eight sewing machines (the women also did their handicrafts there).

The Country Club was administered by the English military authorities, with whom the Polish administration cooperated. The British, with Captain S. Allan as the camp commandant, were responsible for: general administration, food and food stores, sanitation and hygiene, safety and discipline in the camp (with the close participation of the Poles), matters of premises and equipment, matters of unloading and loading transports, mail and postal censorship. The Polish side took on: education, culture and education, as well as the administration of outgoing transports, remuneration of Polish officers, matters of supplying refugees with clothing and communication with other centers of Polish refugees. The camp administration therefore included a Polish staff, which changed during the existence of the camp. In 1943, it consisted of: Andrzej Terlecki – the administrative equivalent of the British commandant, Jerzy Banasz – translator, Milica Koczorowska – clerk, Alicja Nowosielska – messenger, Józef Zalewski – storekeeper, Dominika Ćwiczyńska – head of the children’s kitchen, Amelia Kotlarczyk – deputy head of the children’s kitchen, and hospital staff, i.e. Zofia Krzyczewska and Eryk Walisko – doctors of the Infirmary, Maria Chełstowska and Irena Jaworowska – sisters, Anna Kuśnierz and Zofia Piwowar – nurses. A Citizens’ Committee consisting of five people was established, whose task was to coordinate cultural life in the camp and participate in the work of the administration when necessary.

The Polish refugees in the Country Club were naturally, like all other Poles evacuated to the subcontinent, under the care of the Delegation of the Ministry of Labour and Social Welfare (MPpiOS) of the Polish government in London. In Karachi there was a branch of the MPiOS, acting on behalf of and for the benefit of the MPiOS Delegation, but not issuing any regulations or ordinances itself. The branch employed: Zygmunt Rosada – manager, Hieronim Serwacki – his deputy, Józef Zalewski – accountant, Zofia Kiełbińska – translator, Irena Szutkowska – secretary-cashier and four Indian servants. In connection with the performance of various duties, the manager and his deputy, as well as individual employees of the branch, often commuted to the camp from Karachi. Mr. Rosada also looked after and visited the girls in the St. Patrick’s convent.

British military funds covered the entire expenses for feeding the people and maintaining the camp. Food rations were the same as those received by the English military (with medical supplements). In addition, the children received supplements in the form of milk soups, cocoa and fruit. The same allowance was received by the sick (according to the decision of the chief physician of the camp – Dr. H. Lewett), infants and breastfeeding mothers.

There were three collective kitchens in the Country Club. The adult kitchen employed 27 people, who served about a thousand adult refugees. The children’s kitchen, with a staff of nine, served 529 children, and the dining room for them employed 8 people. The daily menu in the camp was usually: breakfast (tea, bread, margarine and cheese or jam), lunch (meat dish with vegetables, pudding and tea) and dinner (soup, meat dish with vegetables, pudding and tea). Bread was also served with lunch and dinner. The dishes were prepared by Indian cooks. Indians were employed for all the heavier work in the camp. Polish women served only in the canteen and did some of the lighter work in the kitchen.

Children up to the age of six received separate meals, which were prepared by Polish cooks. There was also Polish staff in the children’s canteen. The kitchen and children’s canteen were located in a separate tent and were supervised by the chief physician of the camp. Some products were purchased additionally for the children’s kitchen. All costs related to this were covered from special funds. Meals for the youngest were as follows: first breakfast (groats, milk, bread), second breakfast (bread with butter and fruit or an egg twice a week), lunch (soup, meat, vegetables, pudding, tea, bread), afternoon snack (cakes or bread with butter, fruit), supper (groats or another flour dish, coffee with milk, bread).

The food was quite sufficient for the refugees, although not very diverse. The only variety was fresh fruit, which could be purchased locally and, from time to time, so-called iron rations of the American army, considered delicacies at the time, such as ham and eggs, chocolate, biscuits, etc.

Everyday life at the Country Club went on in a set rhythm, to which all the inhabitants of the camp were subject, although – it is worth noting – a certain number of people were employed outside the Country Club, in a nearby American military camp, assembling parachutes. In the first years of the refugee camp’s existence, the Poles built a wooden church-chapel, where masses were held, although until 1943 there was no permanent priest. This was partly due to the fact that the camp was not expected to exist for a long time, but as the months of its operation passed, the Consulate General of the Republic of Poland assigned a Polish priest – Antoni Jankowski – to the Country Club. He provided pastoral care there from August 1943 until the liquidation of the settlement. Organizing education was also a problem, because in the transit camp children and teachers changed very often. However, it was possible to conduct education. An improvised school was set up in several tents connected together, where education was conducted in four grades despite the lack of textbooks.

There was also a kindergarten and an orphanage in the camp. However, the youth spent their time not only studying – their participation in scout units operating in the camp was quite common. Adults participated in cultural life – there was a club in the Country Club (with press and brochures to read – mostly in English), various events were organized, such as theater performances, sports tournaments, etc. There were also interest groups, workshops, e.g. handicrafts. A

very important place in the camp was the hospital. Its staff, apart from the permanent staff, changed. From 1942 until the liquidation of the camp in 1945, it was staffed by: the chief physician Dr. H. Lewett, Dr. Kalisz (a Pole in the British army), Dr. Jerzy Tiachow, who was later transferred to the housing estate in Valivade. The medical staff included the following sisters: Irena Jaworowska Irena – superior, Adela Ślusarczyk, Krystyna Maron, Krystyna Kernberg, Fryderyka Kernberg and Paulina Benal. The hospital (basically a sick bay) consisted of a group of separate tents. The outpatient clinic, pharmacy and dental office were located in a small wooden house. A smaller tent adjoined the large hospital tent, which served as the sisters’ duty room. Importantly, the hospital had its own analytical laboratory. Admissions in the outpatient clinic lasted during the day at designated hours, and patients were admitted separately in the dental office. In emergencies, patients could report to the doctor on duty at any time of the day. Serious cases and those requiring X-rays were sent to the military hospital in Karachi.

The refugees were mostly ill with skin and eye diseases, dysentery, malaria, and children with whooping cough and mumps. Those suffering from malaria and diarrhea were placed in separate tents. The hospital used the camp kitchen, just like the residents, but they were fed diets recommended by doctors. A separate dining room in the tent was designated for the staff. Hospital dishes were also washed separately.

In February 1945, the final liquidation of the Country Club transit camp began. All those who had remained in the camp up to that time, together with the liquidation staff, were transferred in November of that year to the permanent settlement of Valivade near Kolhapur. The transports were made by a special train. The journey lasted up to 12 days. The liquidation of the Country Club was accompanied by ceremonies – a special mass was held in the camp chapel, and the Poles thanked the camp commandant, Major Allan, for the care and efforts of the British in helping refugees evacuated from the USSR. There was also a special parade with the participation of Cub Scouts and Boy Scouts, followed by a ceremonial farewell party, at which the British guests were entertained by the Polish camp staff, headed by the head of the MPiOS Delegation Branch.

At the end there was a concert performed by an amateur drama group. All this was preceded by a visit of the wife of the governor of the Sind province, Lady Dow, during which there was also a parade of scouts and cubs. Lady Dow inspected the camp for the last time, and the refugees gave her a very warm welcome. Thanking those departing for their warm wishes, Lady Dow said that it was very nice for her to take advantage of the opportunity to help Poles over the past three years and that thanks should also be given to the people of the Sind province for the clothes, schoolbooks and other gifts that the refugees received, mainly thanks to the efforts of Lady Dow herself. A reception was given in her honour, which the school choir brightened up with a programme of original Polish folk songs.

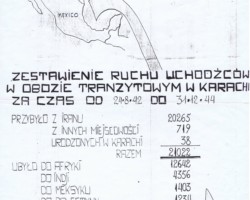

In total, according to various estimates, about 20-21 thousand people passed through the Country Club transit camp operating in the years 1942-1945. Not all of them later ended up in the depths of India in other centres where the Polish population was staying (mainly in Valivade). A large part of them, after staying in Karachi and its surroundings, and after being transported by ship, found themselves in Africa, Mexico, or New Zealand, where special places were also organized for Poles – former exiles deep into the USSR. Their wartime wanderings, similarly to the odyssey of Poles who found shelter in India, were still ongoing…

There was also another temporary camp for Polish refugees next to Karachi – in the town of Malir. It was established in early 1943, when it turned out that the Country Club could not accommodate the numerous Polish refugees arriving from Iran.

Kira Banasińska, the wife of Eugeniusz – the Polish consul general in Bombay, learned from British General Brady that in the town of Malir, occupied by American troops, there were many empty barracks where Poles could be accommodated. She went on a reconnaissance trip. On site, she was shown the camp buildings, and British Major Hinckle explained: “These are completely new buildings, never used before, solidly built, with cement floors and verandas. Good sanitary facilities, plenty of water. Large and spacious dining rooms, as well as a number of separate houses for the administration. The entire district is located somewhat separately from the part occupied by American or English soldiers, far from the bazaars and fortifications.” It became clear that conditions for refugees in Malir were even better than in the Country Club. And so in March 1943, some of the people from the transit camp there, including children from the orphanage, were transported to Malir.

The Polish authorities, in the person of Wiktor Styburski as temporary head of the Delegation of the Ministry of Labour and Social Welfare, took care of the administrative organization of the camp. Captain Władysław Jagiełłowicz was appointed starosta, who received a letter from the Delegation of the Ministry of Labour and Social Welfare with guidelines: “Although the temporary camp in Malir is planned for a short period of time (three months), it should be organized in such a way as to give the residents a sense of stability. In addition to the essentials: food, accommodation, medical care and clothing, special care should be given to schools and cultural and educational activities. In order to prevent the demoralizing effects of idleness and boredom, jobs should be created for the population. The delegate proposes a large-scale sewing factory that could accept orders from military and other institutions. Shoemaking, carpentry and other workshops are also needed to maintain clothing, footwear and equipment.”

The camp administration that had already been formed consisted of the following units: the starosty headed by Władysław Jagiełłowicz and a secretary, a stenographer, translators and messengers; four departments – supply (under the direction of Ignacy Kasprowicz), cultural and educational (under the direction of Michał Chmielowiec), school (with the headmistress of Primary School No. 1 – Blanka Potocka, the headmistress of Primary School No. 2 – Zygmunt Ejchorszt and the headmistress of the kindergarten Maria Bożko; (there were two kindergartens in the camp, at each school, and later also junior high school and high school classes) and work (with the headmistress Witold Bidakowski). In addition, there was a nursery from Isfahan in the camp under the direction of the above-mentioned Zygmunt Ejchorszt and the care of numerous staff, including teachers, nannies, as well as many people responsible for, among other things, feeding the youngest children. These children were transported to Malir from Iran and gathered – together with other orphans, including those transferred from the Country Club – in an educational institution – officially named the Gen. Władysław Sikorski (later transferred to Valivade). There were also: the Citizens’ Security Guard, the records department, the Sanitary Service and the managers of residential areas. Two Catholic priests were responsible for the pastoral care.

Thus, the camp in Malir was an administrative and economic unit, managed by the camp mayor with the help of permanent camp employees, and was directly subordinate to the delegate of the Ministry of Labour and Social Welfare in India, with its headquarters in Bombay, or its branch in Karachi, where the temporary delegate was vice-consul J. Gruja. A liaison officer of the British authorities for economic and administrative matters served with the mayor of the camp.

The starost was bound by the recommendations of the MPiOS Delegation, which also defined his competences – he was to make decisions in matters such as safety or health. He had disciplinary powers – he had the right to impose administrative and financial penalties, and “in extreme cases” to apply ordinary arrest for up to 14 days.

The starost was required to submit a three-month budget estimate to the MPiOS Delegation, as well as to keep strict accounting records through a cash book, inventory book, material book and clothing book. Every month he also had to send various reports to the Polish authorities (incidentally, managers, starosts and commandants of other refugee centers for Poles in India were obliged to do similar things). The transit camp in Malir operated effectively. The registry department kept a file of its residents and recorded the movements of refugees between hospitals – in Karachi, where more serious illnesses were treated, and in the camp. Thanks to this, it was always known what the number of refugees was at a given time in the camp. The registry department also kept a file of specialists and the division of the population by gender. Other administrative entities carried out their tasks in a similarly structured manner. However, the Labor Department had little scope for action. Initially, only a sewing room and a shoemaker’s workshop were opened in the camp, where only the managers were permanent employees, and others were hired and paid for their work on a daily basis as needed. The latest to open was a shoemaker’s workshop, where six shoemakers and a cashier worked. Prices there depended on the type of repair and the cost of obtaining leather on the market. In turn, the concession for a watchmaker’s workshop, and only for repairs, was granted to HIndus. On the initiative of engineer Jan Pacak, a doll and toy workshop, a handicraft workshop, a carpentry workshop, and a hand weaving workshop were opened, for which engineer Pacak himself assembled the weaving workshop (he also took over the management of the Labor Department after Witold Bidakowski and the organizational spearhead left for Valivade in June 1943). The pace of organization was fast, as exemplified by the aforementioned sewing room – opened on April 19, it had six sewing machines, 24 female workers and one cutting machine. It produced aprons for workers in the dining rooms, curtains for the recreation rooms, theatre costumes, scout uniforms (there were two male and three female units in the camp) and uniforms for members of the Citizens’ Security Service. There were 44 guards on duty in the camp, ensuring the safety of the residents. Although crime in the camp was only of an “administrative and orderly nature”, there were various incidents, such as when an American soldier, and on another occasion two Hindu soldiers, tried to enter one of the blocks inhabited by Polish refugees, or when Muslim kidnappers of girls sneaked into the bedroom of the educational institution, who were scared away by the immediate alarm of the guards (the attackers were dealt with by the English authorities). The administration included a post office in the camp, which provided invaluable services in forwarding and receiving letters to families serving in the Polish Army in the East.

The role of the Sanitariat was very important, dealing with all matters related to the health of the camp residents and sanitary and order issues. The camp had a hospital and an outpatient clinic, a camp pharmacy and a sanitary brigade for sanitary supervision. It is worth emphasizing that during the creation of the camp administration, a shortage of specialists was felt. The shortage of dentists was particularly acute. In order to use the services of a dentist who removed teeth, people went to the Country Club, this was done regularly, three times a week, while twice a week trips were organized to Karachi to the dentist for treatment and filling of diseased teeth – (the costs were covered by the MPiOS Delegation), especially in the context of the youngest, because the condition of children’s teeth after their exile in the USSR required special care. In this matter, it was decided to ask the British authorities for help.

The camp hospital consisted of two blocks that could accommodate 100 beds (the above-mentioned pharmacy and outpatient clinic were located at the hospital). The doctors in charge were Dr. Maria Wysocka and Dr. Barbara Brunnée, and the administrative doctor Dr. Leon Koziełkowski. In addition to the superior sister, Mrs. Holland, who worked on an honorary basis, the hospital was staffed by, among others, six sisters of the Polish Red Cross Emergency Medical Service and eight nurses. The hospital had long, bright rooms with rows of beds along the walls and a wide passage in the middle, and a small open duty room for the sisters with a buffet in the middle of the room, where the housekeeper was in charge and issued bed linen, and then there was the office of the administrative doctor and the superior sister. Food for the sick was provided by the camp kitchen. The second hospital block, a little further away from the first, was organized similarly. Halfway between the hospital blocks were showers, and a little closer to the blocks – toilets. Adults and children filled the beds – sometimes younger children had to be put in twos in one bed, because malaria attacked many of them, as did skin diseases caused by avitaminosis brought from the USSR. In addition, there were eczema of the tropical type, and the heat made treatment difficult, because treating skin diseases with various ointments and dressings, while using oral agents and providing appropriate nutrition, was ineffective.

In June 1943, vaccinations against typhus were started in the outpatient clinic, followed by two more at monthly intervals. They were mandatory for all camp residents.

Initially, two areas were established on the vast camp grounds: the first and the second, each headed by a manager and managers of residential blocks, of which there were seven. The managers of the blocks in the Isfahan orphanage were female educators living in the blocks. This was the administrative structure in which life was to take place in the “Polish Camp in Malir, Karachi, India”, as it was officially called.

After the desert sands of the Country Club, a bit of greenery in Malir, only a dozen or so kilometres away, delighted the newcomers. After the tents and sands that covered everything, brick buildings with cement floors had to satisfy the Poles, but Malir was only a transit camp before leaving for the permanent settlement in Valivade, which was still unfinished at the beginning of 1943. However, Malir offered very decent conditions – blocks with six to nine rooms, each with 14 beds. On the bed there was a mattress, a pillow, a mosquito net. The block housed 90–125 people; there were also a number of two-person apartments. The bathrooms had 16 showers. For three blocks. They were distributed in the same way for three blocks: a laundry room with eight taps and one toilet for 16 people. Drinking water for refugees was chlorinated. There were also two iron garbage cans with lids and fire-proof sandboxes for three residential blocks. Maintaining order in the rooms was the responsibility of its residents in order to maintain hygiene.

Since all meals came from a common boiler, residents were designated for kitchen duty by district managers, acting on a voluntary basis. The Polish authorities assumed that all refugees from the camp capable of mental or physical work could be called up for occasional community service. Unpaid work concerned activities in control and supervisory committees, in organizing cultural and educational events and all sanitary and orderly tasks, since the cleanliness of the camp had to be maintained by the residents themselves. Only people over 55 and children under 14 and those with sick leave were exempt from this. Due to the climate, no non-urgent work was performed between 11:00 and 16:00 – so a rhythm of 12 hours of physical work and 18 hours of mental work per week was adopted.

The camp residents were fed by an Indian contractor and the kitchen staff, only the Polish manager watched over the Polish menu, and Polish “waitresses” were appointed in the dining room. A doctor was always present when meat was collected to check its freshness (bad meat was doused with kerosene and burned). At the beginning of April 1943, the starost Jagiełłowicz appointed a citizens’ commission to inspect food products for all three kitchens existing in the camp. The menu was established with the contractor for each ten-day month, and the menus were posted in the dining rooms. Coupons were issued for receiving meals.

“Polish Camp in Malir, Karachi, India” could accommodate over 2,200 refugees, their number in 1943 was however greater, the limits were exceeded due to the very large influx of Poles and their longer than expected stay, and the necessity to wait for the completion of the permanent settlement for Poles in Valivade. However, it was soon opened and in 1943 refugees began leaving Malir. On June 8, the organizational spearhead with starosta Jagiełłowicz left, in July over a thousand more people left the camp, others followed in August, among them over 500 children from the orphanage (educational facility). Some of the youngest orphans went from Malir to the Country Club (some children, orphans or half-orphans depending on, also left for Mexico). In addition to them, a small group with priest Antoni Jankowski and volunteers for the Women’s Auxiliary Air Service in the Polish army left there (in the Polish Army in the USSR, the Women’s Auxiliary Service existed from September 1941, and recruitment began in August. After General Władysław Anders moved the army to the Middle East, it became possible to recruit some volunteers for the needs of the air force, and so on December 14, 1942, a regulation was announced on recruitment to service in the air force, and on February 19, 1943, on the establishment of the Women’s Auxiliary Air Service, which, pursuant to an agreement – of March 23, 1943 – between Poles and the British Air Ministry, became part of the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force).

Malir was deserted, new life awaited the refugees who had been staying there until then in Valivade. Refugees who did not leave for the Indian subcontinent eventually ended up in Africa or Mexico from Karachi (as was the case with some children), where the climate was much better, living conditions were completely different and… new hope for a quick change of wandering fate, an end to the war odyssey and a return to their homes in the Borderlands, which was soon to be thwarted by the approaching November conference of the leaders of the Soviet Union, England and the United States in Tehran.

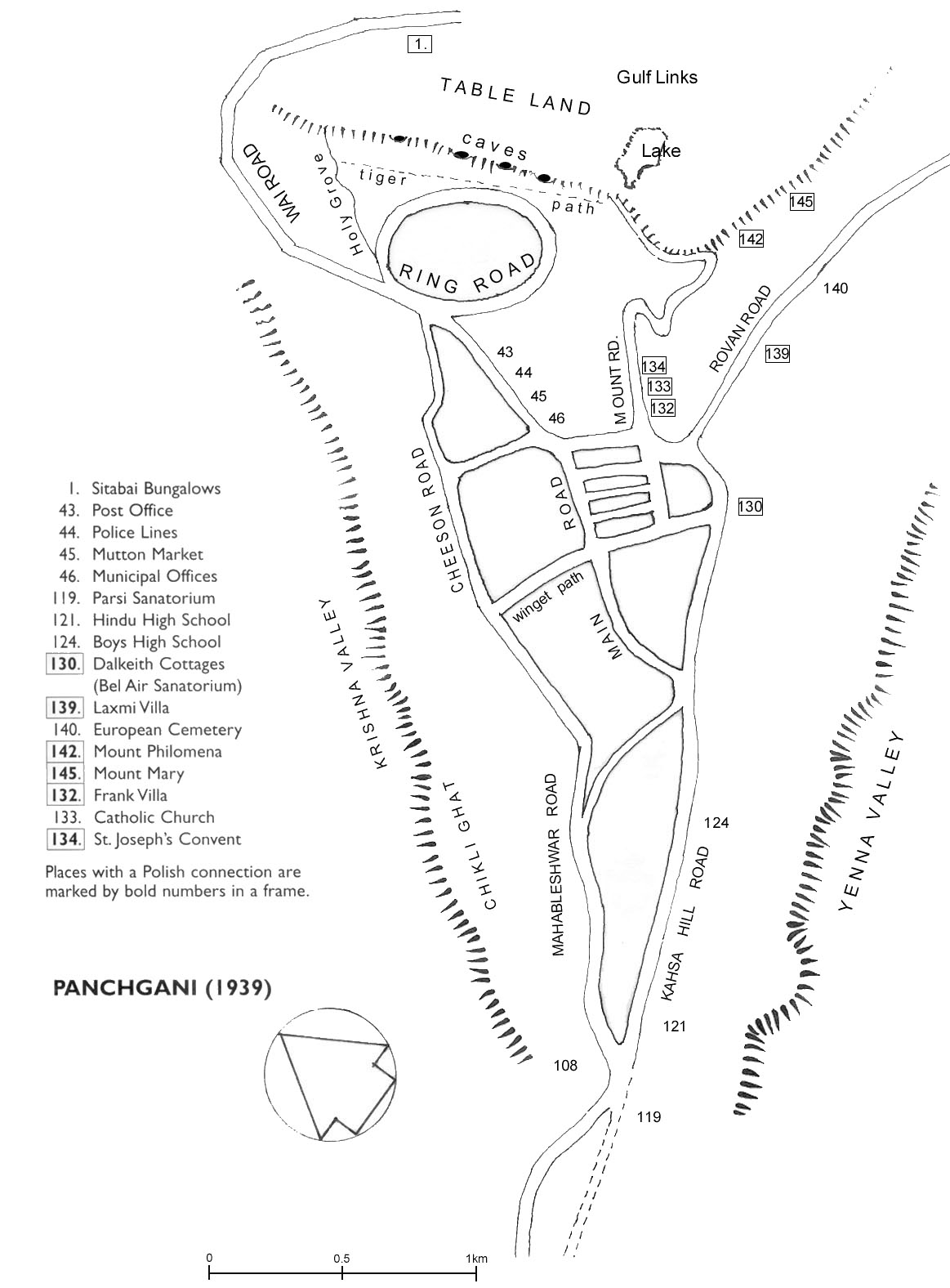

The most important centres for Polish refugees in India also included the spa town of Panchgani, where orphans who had arrived in India from the USSR in 1942 in the first land transport of the Bombay rescue expedition of the Polish Red Cross Delegation were initially sent, and who required sanatorium treatment. After a short stay in a temporary centre in Bandra, they were sent to Panchgani, a town already known for many years with a spa tradition, where there were health and recreation facilities, mainly aimed at helping people at risk of tuberculosis and suffering from it.

Thus, in the first half of 1942 – under the care of Hanka Ordonówna (born Maria Anna Tyszkiewicz, née Pietruszyńska), who also required treatment and was sick after being exiled in Soviet Uzbekistan – five girls arrived in Panchgani: Alicja Król, Janina Puk, Władysława Dobolewicz, Mila Kot and Jadwiga Misiur. Soon more Polish children arrived.

The doctors at the Bel-Air tuberculosis sanatorium, where the youngest Polish refugees ended up, were: Dr. H. Jacoby and Dr. FC DaCunha, who devoted all their medical knowledge to the children. They also helped adults fighting tuberculosis, because over time, not only did the health resort receive groups of the youngest Polish refugees brought to India from the USSR in various ways, but also adults rescued from Soviet territory who required treatment or long-term rest after hard labor in exile and long-term evacuation through Iran. It is worth noting that advanced tuberculosis was treated in closed sanatoriums, while its milder forms were treated using the climatic method, by staying in a sanatorium and exposing patients to the effects of favorable weather in a mountainous town located over 200 km south of Bombay.

Since in the main Polish settlements in India in Balachadi and Valivade there were a certain number of tuberculosis patients who had a full chance of recovery, in order to save their health the Polish Delegation of the Ministry of Labour and Social Welfare considered Panchgani to be an ideal place to open a health centre for refugees there

. After long consultations, this took place in 1943. It was also planned to establish a Polish sanatorium for tuberculosis patients, because in Indian sanatoriums there were everyday difficulties related to the different customs of Indian patients, their lack of hygiene, the language barrier and dietary problems (for example, the director of the sanatorium in Panchgani, Indus, forbade feeding Polish refugees beef, which Indians do not eat, so Polish patients were forced to eat only lamb). Due to the latter, when the MPiOS Delegation opened the Social Welfare Centre, a Polish kitchen was set up in the sanatorium, serving nutritious dishes to the satisfaction of the patients, which the local doctor approved and considered very valuable. Constant correspondence was also maintained between the Polish centre and the patients, so that they did not feel lonely. There were periods when the number of Poles treated in Panchgani increased to 200 people (including children). The patients were provided with newspapers and books, and the open common room was used for meetings and social gatherings in more favourable conditions.

Officially, the Social Welfare Centre in Panchgani was established in August 1943.

The crowning achievement of all efforts was the purchase of a villa and the organization of administration and the lives of the wards. This was mentioned, among other things, in the report of the Ministry of Labor and Social Welfare Delegation from November 1944, which provided a list of spa villas that were managed by Poles. Thus: the Mount Mary building housed the center’s office, kitchen, food warehouse and dining room for children from the Frank and Laxmi villas, dining rooms for employees and vacationers, as well as employees’ apartments. The Mount Philomena villa was occupied by the center’s employees and their families, as well as vacationers from the MPiOS Delegation. The Laxmi villa was used for convalescence by Polish children, and housed an outpatient clinic, apartments for the medical sister and the teacher, and two classes of the primary school. The Frank villa, located near the Catholic church, was inhabited by older children (five boys, four girls), employees of the center, and also housed one class of the primary school. The Sithabai villa was located far from the four previously mentioned villas, and had to be reached by car, which was willingly lent to the centre by the very kind superior sister of the convent run by the congregation of the Daughters of the Holy Cross, where many Polish girls studied. In fact, it was not one building, but a complex of them – single-storey houses at the Parsi High School, two of which were inhabited by older children, and one by the centre’s employees and holidaymakers from the MPiOS Delegation.

The next managers of the Social Welfare Centre in Panchgani were: Amelia Kotlarczyk, Stanisław Dzięglewski and Kazimierz Łęczyński. The office staff of the centre consisted of: Łucja Tabaczyńska – secretary, Magdalena Stelmach – manager, Waleria Płocka – bookkeeper, Wanda Łęczyńska – manager of the Polish kitchen. The educators of the youngest were: Franciszka Dubicka, Zofia Maruniak, Stefania Wojakowska, Mieczysław Pałys. Periodically, graduates of the general secondary school from Valivade came to help the educators, including Eliza Harbuz, Janina Sipika, Jadwiga Wałdoch.

The residents of the Social Welfare Centre lived a regular daily routine. Its rhythm was determined by meals, walks, treatments and – for the children – learning. It was conducted under the supervision of qualified teachers, profiled according to the needs and abilities of students who, due to ailments, could not receive education in the normal school mode, and therefore were organized (after unsuccessful attempts to conduct education in the ordinary framework of a primary school) in groups of two courses: the Primary School Course and the Secondary School Course. Students used the resources of the center’s library, this also applied to young people educated in the Convent of St. George and local Anglican schools.

The head physician of the sanatorium – Dr. FC DaCunha, a world-famous lung disease physician, was kind to the outpatient clinic of the Polish center, with which he cooperated in the treatment of sick refugees from the USSR. During 1944, after the arrival of a group of doctors from the Polish Army in the East, Dr. Samuel Wieselberg worked in Panchgani for a short time, and then until the liquidation of the Social Welfare Center – Dr. Grażyna Miklaszewska-Czekańska. Dr. Maksymilian Rosenthal commuted from Valivade to run a dental office in Panchgani. The permanent nursing staff consisted of sisters from the Polish Red Cross Emergency Department: Loda Atras, Janina Gawron, Waleria Zawadowska and sometimes Wanda Łagunowa – a graduate of the Higher School of Nursing in Poland.

The sanatorium was well equipped and its residential pavilions were very comfortable. Some Polish children learned the local language in Panchgani, and the Hindus learned Polish. Polish girls taught Indian girls how to embroider Vistula patterns provided by a teacher from the centre. Children who had already undergone effective treatment in the sanatorium lived in the Laxmi villa on the grounds of the centre under the care of a doctor and a teacher. In other villas, climatic treatment was applied to convalescents after serious illnesses and to weakened children. In time, Panchgani became the place of residence for almost the entire period of their stay in India. However, most Poles stayed there temporarily, to improve their health.

Apart from people treating their lung diseases, there were also those from the Valivade and Balachadi estates whose health required rest, getting rid of worries for at least a few weeks and engaging in everyday activities in climatic conditions much better than those prevailing in the permanent settlements. Such people in need, including a large percentage of school children, were referred to Panchgani by doctors from the estates. It was also possible to treat oneself to a holiday in Panchgani at one’s own expense, if one could afford such an expense. All of them took advantage of the medical advice and care of the Social Welfare Centre outpatient clinic, where in 1946 even the treatment of bone tuberculosis and climatic treatment of infants were initiated.

The Polish group in Panchgani was complemented by male youth from St. Peter’s Boys High School and a larger group of female youth from St. Joseph’s Convent, where girls were educated by nuns from the congregation of the Daughters of the Holy Cross. The education there took place, of course, independently of the education of sick children in school courses as part of the Social Welfare Centre. The nuns were involved in more than just educational activities at the health resort (young Polish women went there mainly to learn English, but they also took other, different kinds of lessons – music, singing, drawing, history, literature, mathematics, geography, chemistry, botany… – and Christian religion, because not only regular lessons ended with exams, but also catechism classes or evangelical texts).

The sisters also cared for prisoners and orphans. Their monastery, located in the mountains, was picturesquely immersed in greenery above the spa town spreading below. The spacious interiors of the monastery included, among others, classrooms and workshops, a music room equipped with pianos, a rich library with books from many fields and a spacious dining room. In addition, there was a gymnasium, where plays were also staged, concerts and other types of artistic events were organised, often prepared by Polish women who wanted to familiarise the natives with, among other things, Polish folk customs. Sometimes the hall resounded with music, dances and even silent film screenings, which aroused great interest among the youth and provided them with the entertainment they needed.

The education of Polish girls in the convent was financed by the MPiOS Delegation. The Polish government thus paid for their stay in Panchgani, clothing, scholarships and financed the employment of a Polish teacher of their native language (they had separate classes in this subject; during these classes, non-Polish students attended French or Hindi classes).

It is worth emphasizing that the girls achieved excellent results, sometimes great results even in English classes, leaving behind their Indian colleagues, for whom this language was known from the earliest years. They moved smoothly from class to class, even though the English system in which they received education required a lot of work from them. The school year in the Convent of St. Joseph began in February and ended in December. The education took place in the discipline imposed by the sisters of the congregation (they came from different countries, including England and Germany – countries that were at deadly war with each other at the time). Classes were divided by prayer, and the students had to wear uniforms. Talented Polish girls were able to complete two classes in one school year.

On November 11, 1945, after mass in the monastery chapel, a commemorative plaque was consecrated in the convent with inscriptions in Polish and English: “in memory of the stay of Polish children who, expelled from their homeland, were educated in this school in an atmosphere of kindness and cordiality – this plaque was funded by grateful Poles.” A delegate of the Polish government – Stanisław Darlewski – arrived at the ceremony, which was connected with the celebration of the national holiday of regaining independence. After the unveiling of the plaque, in the evening, an academy was held in Panchgani with speeches and artistic performances by Polish and English youth.

Similar things happened in other convents and in Anglican schools, where young Poles (boys and girls) were educated; in other places. These were: Mount Abu, Karachi and Bombay. Young people were also sent there for educational purposes, especially to learn and improve their English.

There were no places or funds for fees for all those who wanted to attend. Older students, those on the threshold of further studies or work and those who showed linguistic talent, were chosen. The monastery schools to which they were sent were run by European teachers, operated in a system modelled on English “public schools” (this name is misleading to the reader, because these were elite private schools) and prepared for English exams. The level of education in them was generally quite high, there was also great discipline and an almost monastic-barracks rigour, combined, however, with caring care.

The first to leave for English schools were young people from the settlement for Polish children in Balachadi, especially since there were no older secondary school classes in this settlement. Already in January 1943, a group of 10 girls under the care of Miss Wanda Ruszczyc were sent to the Convent of St. Joseph in Karachi. After some time, several girls from the transit camps of Country Club and Malir joined them. At the same time, 15 Polish boys aged 14-16 (also from Balachadi) found themselves in St. Mary’s High School in Mount Abu, run by monks from Ireland. The students there were mainly sons of maharajas, wealthy merchants and entrepreneurs, but the young Poles were well received. In October 1944, some of the boys from Mount Abu left for a naval school in England, the rest were moved to a settlement in Valivade. The third group from Balachadi – 12 girls – found themselves in a convent in Panchgani (run by the same congregation as in Karachi). They were joined by three girls from the camp in Malir. In 1946, there were already 60 young Polish girls in the convent school, including many from Valivade. In Panchgani, the also mentioned St. Peter’s Boys High School accepted a dozen or so Polish boys. In 1946, trips to Bombay began for an eight-month accounting course at the YWCA Commercial School. Some of the girls lived in Bombay at the St. Theresa Home convent, while a shelter of sorts was set up for the rest.

Polish youth were also sent from Valivade to a Jesuit school in Bombay. A group of ten boys aged 16-17 ended up there. The school, run by the monks – St. Mary’s Boys High School – was a private school, operating on the English model, and accepted about 200 students per year, mostly from middle-income homes or receiving state scholarships, and over 400 students from very wealthy homes. The Polish group was enrolled in the boarding school. It is worth noting that in all the schools, the youth had additional Polish lessons and information about Poland.

Finances were a very important aspect of the education of Polish youth in Karachi, Bombay and Panchgani.

The cost of living for female students in Bombay was considerable. Although the tuition fee at the YWCA Commercial School was only 25 rupees a month, there was also housing and board, the cost of school supplies and “pocket money” for travel and other expenses, which in total was three times the monthly allowance paid to residents of the Valivade housing estate. The cost of education at St. Mary’s Boys High School in Bombay and St. Joseph’s Convent in Panchgani was slightly lower (around 80 rupees a month for tuition and board), but financial difficulties were the most difficult factor in sending Polish youth to study outside the centers.

Nevertheless, the Polish authorities were aware that the issue of educating the younger generation, whose proper education had been brutally interrupted by the Soviet occupation in the Borderlands and then in exile, was one of the most important tasks. It is worth emphasizing that in July 1943, the Ministry of Religious Denominations and Public Enlightenment in London opened a facility for Education and Schooling at the Delegation of the Ministry of Labor and Social Welfare in Bombay in the camps and settlements of Polish refugees in India. The task of the facility was to provide teachers and young people with conditions for normal and systematic work in the field of education and upbringing of the young generation and preparing them to return to Poland. The facility cooperated closely with the Delegation of the Ministry of Labor and Social Welfare, and above all with its cultural and educational department, but in school matters it was subordinate to the Office of Education and School Affairs in Tehran. Its director was appointed mgr Michał Goławski, who arrived in Bombay from Tehran on May 27, 1943. In September 1943, the dynamic development of all kinds of schools and courses meant that the institution was developed into an independent Delegation of the Ministry of Religious Denominations and Public Enlightenment. This continued to direct young Poles to various English schools and convents described above, and to coordinate the education of children and youth in schools established in centers for Polish refugees in India.

After a period of increased education in English schools and convents, the youth returned to their permanent settlements in Valivade and Balachadi (most often to Valivade, because young students of convents who found themselves there from the children’s settlement in Balachadi, often did not return there after reaching the age of 15-16, but were transferred to Valivade).

In April 1947, the Poles – patients and the last students of the convent – were transferred from Panchgani to Valivade…

The sick were taken to the care of a local hospital for further treatment, and the children to schools. Two graves of Poles remained in the area of the health resort, as the last director of the centre, Kazimierz Łęczyński, recalls from memory – the late Świeżawska was buried in Panchgani, and the Polish citizen of Jewish origin who died in the sanatorium, was buried in the nearest Jewish cemetery in the city of Poona.

This was also the final period for the existence of a permanent refugee settlement in Valivade (the settlement for Polish children in Balachadi was closed in 1946) – families were being reunited with members of Anders’ Army at that time, most of whom were already in England, for others repatriation to Poland was underway, some were facing dilemmas related to the decision to finally emigrate.