Quick Links

Transit Camps and Centers for Poles in India

The way in which the liquidation of Polish refugee centers in India was taking place is illustrated in the text by Teresa Glazer, a resident of Valivade. Her record – from the inside, as it were – not devoid of fragments of memories, illustrates not only the facts, but also the dilemmas that accompanied Poles at that time. Here is the record:

Throughout our stay in India, we were waiting for the end of the war and the return to a free homeland. All the academies, sermons in church commemorating various national anniversaries, stories at scout campfires, letters we wrote to the ‘unknown soldiers’, were filled with this hope. Being far from the battlefields, we eagerly caught up on all news about the course of the war: we rejoiced in the victories of the Allies, we were proud of those in which the Polish Armed Forces took part, but from 1943 relations with one of the Allies, namely Soviet Russia, began to deteriorate. In April 1943, news of the discovery in Katyn of the graves of murdered Polish officers and an appeal by the Polish Government to send a delegation of the International Red Cross to Katyn to investigate the matter on the spot, became the reason for Russia to break off diplomatic relations with the Polish Government in London. For Great Britain and the United States, Poland became a troublesome ally, because they feared that its affairs would not spoil relations with the Soviets. Ever since the conference of Roosevelt, Stalin and Churchill in Tehran in late November 1943, it was known that the fate of Eastern and Central Europe had been decided, when Churchill’s plans to attack Germany through the Balkans and for the Allies to take control of the eastern part of the Mediterranean were rejected. Churchill feared that these areas would be given to Russian influence, but he was outvoted by Roosevelt, who naively supported Stalin and remained suspicious of British imperialism. A decision was also made in Tehran regarding Poland’s post-war borders: giving the eastern territories with Lviv and Vilnius to Russia in exchange for territories in the west and north at the expense of Germany. We did not know about it at the time, because it was kept secret. At the Moscow conference in October 1944, there were attempts to merge the communist Polish Committee of National Liberation (PKWN) established in Moscow with the London Government, but no agreement was reached. On January 1, 1945, the PKWN was transformed into the Provisional Government recognized by Russia, with headquarters in Lublin. In February 1945, at the Yalta conference, it turned out that President Roosevelt was not very interested in the fate of Poland, or Central Europe in general. He was already very ill at that time (he died 6 weeks later). He announced then that the United States intended to withdraw troops from Europe in the near future. Churchill tried to defend the Polish cause, recalling that the war had begun over Poland, but his influence had diminished – only America really mattered.

Roosevelt sought Russia’s support in the war against Japan, which was still defending itself. In reward for the enormous Russian contribution to the war and contributing to the fall of Germany, he left Central and Eastern Europe in the sphere of Russian interests. The eastern borders of Poland were officially established along the Curzon Line. A large part of the inhabitants of Valivade came from the Eastern Borderlands, and we all went through exile to Russia, so how could we think of returning to the Country that was to exchange German occupation for Russian? The end of the war was approaching, but there was still no prospect of returning to a free Fatherland. In June 1945, the Provisional Communist Government arrived in Warsaw, and on July 5, this Government was recognized by Great Britain and the United States. At the same time, recognition of the London Government was withdrawn. What will happen to us now? As it turns out from secret documents, which can now be read, this question tormented not only us. It was also asked in the Foreign Office in London. Since November 1944, they have been considering how to make the Poles understand that the responsibility for Polish refugees on British soil should be taken over by an international organization established by the United Nations for the relief of the populations of the countries most affected by the war, in order to relieve the British government. But this had not yet happened. Until July 6, 1945, the London Government financed all Polish posts from funds that came from loans granted to the Polish government by the British government. After the withdrawal of recognition of the Polish Government in London, completely new conditions arose. An ‘Interim Treasury Committee’ was established – a Temporary Treasury Committee to finance the affairs of Polish refugees, consisting of: 7 Poles under the leadership of Ambassador Raczyński and 5 Englishmen from the Ministry of the Treasury under the leadership of W. D. Allen from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Our Consulate in Bombay was planned to be liquidated in August and September 1945. The Lithuanian Consul was to remain as the official representative of the unofficial London Government. From the former employees of the Consulate and Delegation, a Central Social Welfare Office was established in Bombay, consisting of 14 people, to assist in the administration of the settlements, to maintain contact with the Indian Government, to continue the publication of the Pole in India, which was essential for informing refugees who did not know English about events in the world, and to supervise education. The Consulate was to be staffed by new officials sent by the Warsaw government, but they had no right to interfere with the refugees. The administration of the camps was subordinate to the chief representative of the Indian government for refugees, Captain Webb. The consul’s diplomatic privileges were withdrawn, but correspondence for the Provisional Revenue Committee in London was to travel in the diplomatic baggage of the Indian Government.

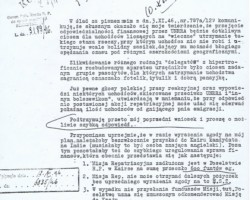

In a letter from the Treasury in London, H. H. Eggers writes to R. N. Gilchrist in the India Office that he is sending him a new payroll for Polish workers and asks that a copy be returned to him because he is sending the original. The Temporary Treasury Committee approved the continuation of pay for Polish artists and scientists. In a letter dated July 21, 1945, Captain Webb writes to the Resident of Kolhapur, Colonel Harvey, that the Consul has suggested appointing a British camp commandant who would stand above the political divisions among the Poles (those who still supported the London Government and those who were prepared to recognize the Lublin Government). Colonel Neate was considered a suitable candidate for commandant. He had two deputies to work with him: Mr. Button for finance and Captain Jagiełłowicz for social welfare. He was appointed camp commandant on October 17, 1945. “The relations between the Delegation and the Indian Government should not change from those which existed before July 6,” writes Gilchrist of the India Office in Whitehall, London. Such was the situation on our doorstep – in India. The more general position of the Polish refugees was rather unclear. In a debate in the House of Commons in London on February 28, 1945, Prime Minister Churchill said that he hoped that the Polish forces which had fought so bravely under British command would be able to return to Poland if the Poles could form a government more representative of the whole nation than the London or Provisional Governments in Poland had hitherto done. “Should that be impossible,” he continued, “the British Government will never forget their debt to the Polish forces. I hope that we shall be able to offer them citizenship and the opportunity of settling in the British Empire. I cannot make a statement on this matter to-day, as it requires discussion between Great Britain and the Dominions, but I think it will be considered an honour to have such gallant soldiers living among us.” After the change of Government to a Labour one in July 1945, the official attitude towards the Polish forces under British command did not change, but there was no satisfaction in the fact that all efforts to persuade them to return had been in vain. It was felt that they would have to be re-educated to work in Great Britain and the Empire. A letter sent from the Foreign Office on 21st September 1945 states that the Foreign Secretary, E. Bevin, had directed that the position of some 40,000 Polish refugees, who had been maintained for some years in exile by the Polish Government, should be reconsidered and that they should henceforth be dealt with by the United Nations’ Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA). In correspondence between London and diplomatic missions it was assumed that the main reason for this change of position on the British side was the desire to relieve itself of the burden of financing refugee care and to transfer it to UNRRA, to which the British Government already pays very considerable sums.

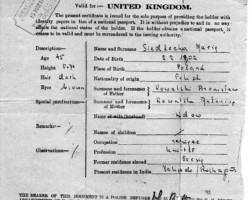

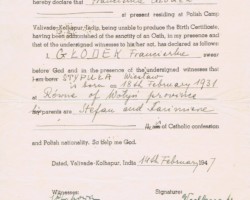

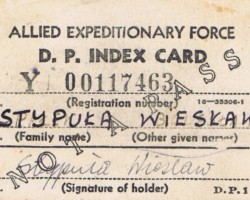

UNRRA, established in November 1943, became interested in us in January 1945, when instructions were received from the Polish Legation in Cairo to the Delegation in Bombay regarding the registration of refugees. The local UNRRA in Cairo delegated Robert Durrant as its representative in India to register refugees from Allied countries. The documents of the Starosty explain: “UNRRA, as you know, is the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Organization. It operates on behalf of 44 Allied governments, including our government in London, which delegated its representative to UNRRA. One of the main tasks of UNRRA is to prepare the repatriation and transport of millions of war refugees – citizens of Allied countries, to their designated places of permanent residence. The preliminary work preceding repatriation is precisely the registration of refugees, which is to determine their number and the demand for land and sea transport necessary for their repatriation, as well as the direction of repatriation.” In a letter to the district governor of the settlement dated 6 March 1945, delegate Dudryk-Darlewski writes that the Delegation has not yet received a sample registration form, at the same time informing that “UNRRA agrees that refugees may refrain from signing registration cards. However, this institution is of the opinion that a handwritten signature protects against possible later forgery of the content of the registration card.” On March 13, the Delegation reported: “The following data is required to fill out the registration cards: surname and first names, marital status, place of birth, religion, date of birth, number of family members accompanying the person, number of people supported by the person, father’s surname and first names, mother’s first name and maiden name, destination to which the refugee wishes to leave, last place of residence in Poland or place of residence on January 1, 1938, profession and so-called secondary profession – the ability of the person to perform specific work, knowledge of languages in the order of fluency, nationality. The cards were to be kept under lock and key at the estate management office and handed to the owner upon departure. People who do not register would be considered stateless. On the same day, starosta Jagiełłowicz expressed concerns in a letter to the Delegation that if UNRRA advises that refugees sign registration cards to protect them from possible forgery, what guarantee is there that they cannot be forged and with a signature? In addition, people whose place of birth or last residence in Poland was in the territories recognized by the Yalta Conference as belonging to the USSR feared that their data would be used in a way inconsistent with the refugee’s wishes.

(We were not sure then that, according to the Yalta decisions, Soviet citizens were only those who had lived within the borders of the USSR before September 1, 1939.) On March 14, 1945, daily circular no. 24 informed the residents of the Valivade settlement that a representative of UNRRA, Mr. Durrant, had arrived at the settlement and that registration would begin the following day, March 15 from 3 p.m. to 7 p.m. in community center no. 1, and on March 16 from 9 a.m. to 8 p.m. in the theater hall. The starosty recruited many typists from individual offices to do the registration. “We all sat up late at night familiarizing ourselves with the UNRRA registration forms (writes one of the typists, Wiesia Klepacka). In the morning, we waited in the community center by the library for the residents’ applications, but it was a complete fiasco. Throughout the day, a small handful of very old people who had no one in the Polish Army and therefore preferred to report for repatriation to Poland turned up.” District meetings were proposed to provide information on registration with the UNRRA by MPiOS delegate Dudryk-Darlewski. Despite assurances that the UNRRA, whose work is humanitarian and not political in nature, would not repatriate anyone by force, an atmosphere of distrust existed in the settlement. An entry in Halina Rafał’s diary from 15 March 1945 perfectly reflects the mood of the settlement:

“…Yesterday, a representative of the UNRRA arrived at the settlement. The registration of residents with all the data was announced. There was chaos in the settlement. Rumours began to circulate en masse. Almost everyone shouted at the same time: Don’t register; who knows who he is?… Indeed, no one went to the registration. People went completely crazy, not knowing who to listen to, what to do. Our delegate from Bombay stands by this newcomer. Some say he is a communist. That is too much! He almost got hit, because women surrounded him and threatened him with umbrellas, and Mrs. Kocińska, the ‘killed’ woman from Lwów, did not waste her words – she managed to reach him and stab him in the side with her umbrella. In the morning, notes appeared on the blocks, posted by unknown persons. These notes read: Let’s not register, let’s not succumb to propaganda. There is also a lot of talk about this at school, but it is all so complicated and unclear that it is impossible to understand anything. We do not know who to believe, because everyone says something different. A few people registered, and now they want to cross themselves out at once. They go around and whine. Captain Jagiełłowicz is worried, but he sides with the people. Mr. Darlewski is striving to register – and in fact, we do not know what to do. A telegram was sent to the Lithuanian consul (then the Polish consul in India, who replaced Eugeniusz Banasiński at the time) to come and explain the matter. People calmed down a bit. However, the rumors are still circulating, and they are all kinds of rumors.

Letters come from men in the army with warnings not to register anywhere.” This mood of uncertainty and dilemma is confirmed by another entry from Danka Pniewska’s diary, also from the 15th. “…So this UNRRA delegate turned out to be the proverbial stick in an anthill. The entire camp is seething, people are so tense that they are not literally responsible for their actions. Thousands of news and rumors are circulating around the estate, so grotesque that Ela and I burst with laughter when we repeat them to each other. But it is not always funny. People are panicky afraid of Russia and everywhere they smell the collusion of the Lublin government. Mr. Durrant was called a traitor, a communist; Mr. Dudryk-Darlewski was accused of… stealing for two years in the delegation, and now he wants to sell us out…. People are excited, arguing, almost fighting, running around like crazy and… spreading new rumors.”

It is worth noting that these notes, made during all this fuss about registration, as well as correspondence between the district governor and the delegate, indicate that resistance to registration existed despite the advice of Delegate Darlewski, who tried to dispel fears. In a letter dated March 15 to the delegate, District Governor Jagiełłowicz wrote: “The information meetings have not resolved the doubts of many residents so far and have not removed the dilemma. The most objective arguments will not help in these cases, because most residents are military families, making their decision dependent on an agreement with them.” He suggests postponing registration for a period of 4-6 weeks, to give military families a chance to reach an agreement with their loved ones in the army. Mr. Darlewski wrote back the same day that “Mr. Durrant must leave India in 6 weeks, so he cannot wait to register.” In order to calm the population, the Lithuanian Consul and Major Allen were summoned by telegraph, and on 16th March Jagiełłowicz wrote a letter to Robert Durrant, in which he regretted that the UNRRA representative had been unable to fulfil his task due to the lack of trust of the camp inhabitants and tried to explain the reasons for this distrust. The letter is too long. The delegate considered it inadvisable to deliver this letter. Relations between the delegate and the settlement head were deteriorating badly. The delegate threatened the settlement head with dismissal if he sent a letter to Mr Durrant. The delegate urged the head to use his authority and trust and persuade the population to register. The head wanted to know whether informing the population that registration cards could include the disclaimer “I will return to Poland when a constitutional government that I recognise is in power” was appropriate, and what weight could such a statement have? A general meeting of the residents of Valivade Estate was held, where the following points were passed: “The residents of Valivade Estate – Kolhapur resolve as follows, at the meeting held on 18th March 1945:

1. The residents of the Settlement gratefully accept the care of the UNRRA institution.

2. In order to facilitate the UNRRA institution’s orientation regarding the scale of the assistance, they ask

the District Officer to provide all necessary data from the Settlement’s records.

3. The residents of the Settlement ask the Consul General to actively intervene with the authoritative factors in order to include a clause on political prisoners and deportees in the text of the registration sheets.

4. The residents of the Settlement resolve that they will sign the same declarations and at the same time as the sovereign army of the Republic of Poland

. 5. Since the Settlement houses the families of soldiers fighting on the front, the selection of a place of residence, and therefore the signing of the declaration, must be postponed until the Army decides.

This resolution was handed to the Consul General. On March 21, 1945, the Consul General sent a summons to the residents of the Estate, of which the District Governor informed the population in daily circular no. 28:

“… In his appeal to the citizens of the Republic of Poland, the Consul General draws particular attention to the following points:

1. Registration is being carried out on the express order of the Polish Government.

2. The Consul General informed the Government of the Republic of Poland of the doubts of the population and requested a response

to the dispatches sent by the population to the Prime Minister and General Anders.

3. The column Where do you want to go can be left blank.

In the Comments column, you can enter the place where you want to go, I will indicate later.

4. The original card will be kept by the District Governor of the Estate.

5. The registration card may not be signed”

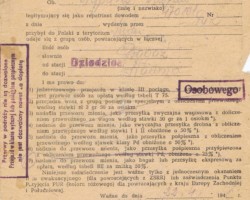

But two days later a telegram arrived from the delegation to stop the registration to UNRRA as a result of the instructions of the MPiOS, and a telegram from the Consul recommended to stop his ‘call to the population’ urging registration. Those who registered had the opportunity to withdraw their cards if they

wished. During Mr. Durrant’s visit, 26 people reported for return to Poland. The list of those returning to the country was opened by Mr. W. Buras, who was stigmatized by the Polish authorities as well as the English ‘Intelligence Bureau’ for spreading communist propaganda. Buras had offended the day-room teacher by listening to the Warsaw radio, as can be seen from the report below: “Radio broadcasts are received at fixed and announced times. ‘Voice of America’ broadcasts are received.

According to the RKO regulation, the device is activated 15 minutes before the broadcast. A certain Buras Władysław, a regular radio listener, in violation of this regulation, arbitrarily took the keys and opened the radio-device for broadcasts of the Warsaw radio and the Warsaw embassy for Poles in Russia. “A complaint about him to the head of the RKO delegation, Ms. Grochocka, during her visit to the Estate, was ineffective, because she only said ‘he is allowed’. Now a very unpleasant period begins in the life of the Estate. The Lithuanian Consul describes it in the following way in a letter to the starosta dated April 16, 1945: “The society is disoriented, divided into groups. Gossip, anonymous letters, slander reign supreme. Every decent person who opposes the mindlessness of the crowd is branded a traitor. There was no trace of civic discipline, loyalty and self-control, which seemed to be the basis of the organizational life of the Poles of the Valivade Settlement.” In April 1945, general indignation was caused by the appointment of Menshikov as the UNRRA representative in Poland, without prior agreement with the London Government. Ambassador Ciechanowski in Washington vigorously protested against the decision of the Director General of UNRRA, Lehman, to establish contact exclusively with the Provisional Government in Lublin, while the London Government was a member of the UNRRA council. “As far as Polish refugees are concerned, the Polish Government takes the position that UNRRA must communicate exclusively with it and that it cannot take any decisions on the possible repatriation of refugees on its own. Ambassador Ciechanowski communicated this position to the Director General of UNRRA, from whom he received an assurance that UNRRA would apply the above principle, which, by the way, was established by SHAEF for Polish refugees located in Germany.”

At that time the delegate and Durrant stated that the stay of the Polish population in India would last at least 18 months, if not 2 years. Therefore, any material assistance from UNRRA does not yet require the completion of repatriation cards. UNRRA rather needs population statistics by sex and age, and organizational data on which to base the calculation of the amount of material assistance. The costs of maintaining the camps after the end of the war, in early 1946, were the subject of correspondence between Henderson, the Foreign Office official in London, and D. Ward at UNRRA (additionally, copies of the letter of 6 February 1946 were sent to Eggers at the Treasury and Gilchrist at the India Office in London). The British authorities complain that the delegate in Bombay is spending 8,000 pounds a month on camps that are already sufficiently supplied.

This increases the cost of maintaining refugees by 20%. They propose to abolish the Refugee Welfare Committee when UNRRA takes over the care of the camps. Emerson Holcomb, director of the UNRRA’s repatriation section in the Middle East, wants to abolish the Committee in Bombay “less for economic reasons than because it has a bad influence on Polish refugees, most of whom are peasants and would certainly have decided to return to Poland long ago if they had received assurances from the People’s Government that they would be able to keep their land and personal property. We should start counter-propaganda and promise them that they need not fear Russia, that they will be taken to a Polish port, not through Russian-occupied territory, and promise warm clothing.”

Gilchrist of the India Office in Whitehall writes back that no guarantees can be given on this subject, because there are no parts of Poland that are not dependent on Russia. Webb’s ninth report to London, dated 9 January 1946, suggesting that most of the Valivade residents would have returned to Poland if not for the influence of the Social Welfare Committee, is inconsistent with his previous statements about resistance to UNRRA registration and return to Poland. Fortunately, London was aware that Captain Webb was under the influence of Holcomb, who uncritically accepted the position of the Warsaw government. Eggers from the Treasury writes to Henderson in the Foreign Office that it would be better not to send this report to UNRRA. How wrong Captain Webb was in claiming that the resistance to registration was due to pressure exerted on the residents by the authorities is illustrated by letters written at that time to their husbands in the army. Fragments of a letter from Ewa Zacharkiewicz to her husband Jan, a corporal in the 14th Rifle Battalion of the II Corps: “…such forms for departure to Poland have been sent to our settlement from the Warsaw government and our authorities are forcing us to fill them in. They tell us that it is absolutely necessary to fill it in because it is needed by the English authorities to reunite with their husbands and they promise us that they will give us warm clothes for the trip and reunite us with our husbands, as long as we fill in these forms and sign them with our own hand. But we do not want their clothes and we do not want to register and fall back into the hands of the Soviets, because although they say that it is nothing terrible, we know very well that it is a trap for us to go to Poland. They say that it is only a list, that if they give us these warm clothes, they will know how many people they have. But they had better not draw the line at us because we know very well what they want to do with us. And I imagine that to give them only clothes, they would not need to demand what they demand and a handwritten signature. Apparently, the same forms that they gave you to fill in to go to Poland…”

Taking over care of Poles in India was to be the first step towards taking over this care and other areas, so it was important to establish relations. The Polish authorities in London hoped that Polish staff would be able to remain and act on behalf of UNRRA after the organization took over care of refugees. In a letter dated May 18, 1946, Ambassador Raczyński wrote to the Lithuanian consul: “…According to the information we have, the administration of the entire care campaign is to remain in the hands of the British authorities. Representatives of UNRRA will be with the local British authorities, tasked mainly with establishing budgets for the needs of the Polish population. The British authorities expressed a demand to UNRRA to retain as much Polish administrative staff as possible. However, according to our information, UNRRA reserved the right to demand the removal of Polish officials involved, for example, in the campaign against repatriation. Despite the assumption by UNRRA of financial responsibility for the care of the Polish population, your contact with me and the Polish side of the ITC should be maintained and information should be continued in the form that you consider most appropriate, not complicating local relations. In this way I present the matter to the British side here and it finds understanding. The nature of these contacts must of course change, because we will no longer be able to give instructions in matters of expenditure or the engagement of personnel, and will mainly concern coordination in matters of a fundamental nature and mutual information. I see no objection to your indicating to the local authorities, if necessary, the necessity of consulting me and coordinating your course of action with me. In accordance with this agreement, ‘Monsieur J. Litewski’ (no longer titled consul), sent to London a copy of the letter of 22 May, which he had received from Captain Webb, in which he informed that negotiations with UNRRA on the assumption of financial care for the Poles in India were nearing completion, but that ‘War Dept. of the Government of India’ recommended the immediate removal of all Poles from India, and he would therefore make efforts to arrange transport. Shortly afterwards, Ambassador Raczyński wrote to Minister Adam Tarnowski that consideration was being given to transporting Polish refugees from India to East Africa or Australia, but the final decision in this matter depended on British factors. The text of the principles for taking over Polish refugee affairs by UNRRA was delivered to the Polish authorities in London on 30 May by Sir Anthony Meyer:

“UNRRA agrees to take over responsibility for the care of Polish refugees, provided that this responsibility consists of:

1. Repatriation of those who wish to repatriate.

2. Reimbursement of the costs of care and maintenance in the countries where the refugees are, both for those who do not wish to repatriate and those who apply for repatriation.

UNRRA will only cover administrative costs and expenses for consumables, but will not cover the costs of purchasing livestock.”

There was no mention of expenditure on education. When asked about this, Sir Anthony replied that “UNRRA

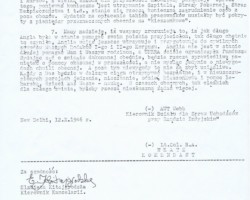

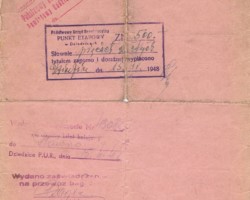

is in principle to cover the expenditure on education, but the extent of this expenditure was to be considered and decided in each area in accordance with local conditions.” UNRRA took over financial responsibility for the maintenance of the Polish settlements in India from August 1, 1946, leaving them under the previous management of the Head of the Refugee Department of the Indian Government, Captain Webb. This organisation returned £5 per person to the Indian Government for 5,084 Polish refugees, which resulted in a deficit of £6,000 per month if expenditure was not reduced. Captain Webb issued a proclamation to the refugees on 12th October 1946, proposing the liquidation of the camps in Balachadi and Panchgani, transferring the residents to Kolhapur, recalling the youth from the English schools outside the camp and appealing to the employees of the Settlement to work without pay in return for free accommodation and board, training and medical assistance. In this proclamation, Captain Webb wrote further: “For the whole of the past period the cost incurred by England for all Poles staying outside their country amounted to £5.5 million per month. The burden has been transferred from the shoulders of Great Britain to the wider organisational planes of the United Nations.”

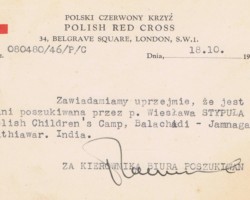

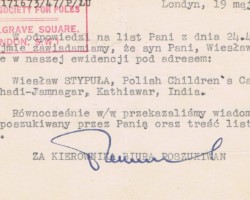

The Poles agreed to the liquidation of Balachadi, but were less willing to close down the health centre in Panchgani, they were opposed to savings in education and did not want to work for free. Captain Webb reported to London on 13 October 1946 that “The Indian Government has asked UNRRA to increase the sum of £5 per month per resident to £6 for the maintenance of refugees and has proposed to replace the staff in the hospital and fire brigade with Indian workers on lower rates and to reduce the allowance paid to the residents of the settlement.” As a result of UNRRA taking over financial responsibility for refugees in India, the Polish Committee for the Protection of Refugees in India, based in Bombay, was liquidated on 12 October 1946. After the liquidation of the Committee, the only Polish institution in India – apart from the Valivade/Kolhapur Settlement – was the Polish Red Cross Delegation in Bombay at 15/17 Queen’s Rd.

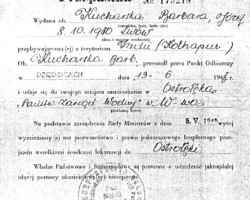

On 28 November, the Lithuanian Consul and most of the former officials of the Delegation and Consulate sailed for Australia. The most senior official of the former Ministry of Social Welfare, Dr T. Lisiecki, remained without a specific position. The registration of the residents of Valivade by UNRRA began on 31 December 1946 and was described in the January issue of the Pole in India as follows: “…As we go to print, the UNRRA representative, Mr Stephen, arrived at the Valivade settlement and is conducting the registration of all refugees. The purpose of the registration is to collect the registration material needed by UNRRA, which – as we know – has assumed financial responsibility for Polish refugees in India since 1 August last year. The registration cards contain personal data, confirmed by the handwritten signature of each refugee. These cards are made in two identical copies, one of which remains in the settlement registration department. Each person who registers receives a registration certificate, which entitles them to receive benefits. Before the registration began, the UNRRA official held a series of conferences with representatives of the refugee movement, during which he explained the purpose and nature of the registration. The main local organization, the Union of Poles in India, received assurances that the registration had nothing to do with repatriation and a guarantee that UNRRA did not intend to force anyone to return. A certain percentage of the settlement residents initially expressed distrust towards the registration being carried out. There were various reasons for this: from partially justified reservations about the policy of the UNRRA authorities to fantastic rumors. The Polish administration and social organizations, recognizing the vital necessity of registration, which is a condition for further use of UNRRA assistance, carried out an action aimed at dispelling fears. Proclamations were issued calling for fulfillment of the registration obligation and the population was informed about the positive position taken towards registration by Polish factors responsible for the fate of the refugees. Regardless of the general registration, the UNRRA representative also deals with the registration of people wishing to leave on the next transport to Poland. In August 1947, UNRRA transferred care of Polish refugees in India to IRO – International Refugee Organisation. The decision to return to Poland was extremely important for thousands of Poles scattered around the world since the beginning of World War II and caused deep spiritual turmoil in families, which is very well reflected in an article by Zbigniew Grabowski entitled Rzecz nadalienia published in Polaku w Niechowia in November 1945, reprinted from Światpol publishing house published in London: “A tragic struggle of Poles with their conscience is currently taking place all over the world.

Tens of thousands are asking themselves whether they should return to the Country or remain abroad. These Poles are trying to find an answer to the tormenting question: do I have the right to remain abroad, since my country, battered and abandoned, needs people and workers? Almost 7 million Polish citizens have been exterminated; the shortage of workers is enormous; Poland is depopulated; there is no question of populating East Prussia or Silesia, because there is no settlement element. What awaits me abroad? – Poles ask themselves. Will I be able to find work or will I get used to foreign surroundings? It is probably unnecessary to explain that all Poles, regardless of their political beliefs, want to return to the Country. They have wanted to return from the beginning of this emigration. If they have reservations, it is only because the form in which Poland has now emerged from the depths of war does not provide any guarantee of freedom and independence, and that everything indicates that Poland is and will remain a vassal state. That is why the decision to return is difficult, that is why it is tragically difficult. It is clear that Polish patriotism and attachment to the land are so strong that in many cases Polish displaced persons to the Reich will decide even on the worst life, just to be in Poland. No one can cast a stone at those who want to return. It is a matter of their conscience. It is not true to claim that some action is being taken to discourage return. There is no such action. Is it necessary to discourage a soldier of the 2nd Corps? He knows many things that cannot be said or written today. If he does not want to return, it is not on the basis of this or that order, because neither the commander nor any brochure or article he has read have any influence on what this soldier will decide. He has seen certain things himself and knows well what to think about them. And that is why we can with dignity repel the claims of this or that propaganda. We can answer each of the callers, each of the cheap shouters, that the issue of returning to Poland is a matter of conscience, and that for both those who return and those who remain, it is a courageous choice, an act of courage.” In the Valivad environment, all of these above-mentioned questions and fears also had their place. The problems of those times were aptly reflected by Jagoda Lempke (Kobordo) in her study of returns to Poland.

“…The discussion was stormy. It was known what those who had someone in the army or in the country were to do. And those who had no one? What influenced the decisions to return to Poland: the desire to reunite with family, longing for the homeland, bitterness and disappointment with the attitude of the Allies, the conviction that the destroyed country needed hands to work and bright minds. Alojzy Grubczak refers to patriotic motives: “Many things separated us from Poland apart from the territorial distance. Suddenly, an opportunity arose to return – not to one’s place of birth, but to one’s homeland.

Our stay abroad in different countries was very overwhelming for us. Not knowing foreign languages, we were alienated, and not having our own homeland, we felt humiliated. Reading the diaries in which experiences were recorded in the heat of the moment allows us to understand how, drawn into the whirlwind of political events, we tried to find our place in life. Helena Szafrańska wrote on 10 October 1947: “What will I do if I cannot believe in emigration? I would like to find myself in the Country as soon as possible. There I have a place for myself, I know what I will do with myself. It does not seem to me at all that roses await me there, but here I am hanging in the air, and there I will stand on the ground.” Families argued, divided or united. For example, 20-year-old Zosia Dudkówna decided to return to Poland on one of the first transports alone (the rest of the family joined later). Alicja Janiszewska did the same, returning to Poland with her brother, while her sister Marysia went to Australia. Some families returned very sparsely, only the lucky ones were complete. Many people returned from Balachadi. The decisions made at that time had a fundamental impact on our lives. The period of the Great Migration of Peoples began, after which an iron curtain fell, separating us from them for many years. The youth belonging to the scouts had a choice of the attitude of scout Hanka Handerek, returning to Poland, or scout Ryś, a fervent supporter of remaining in emigration. Scout Ryś: “Anyone who decides to return to the country is a weak person who is afraid of fighting outside the country.” Scout Hanka had a different opinion: “I hope that you can fight both here and there. If there are more creative individuals in the country, there will be a greater chance of victory.” At school, one of the students recalls that a project to collect money for a farewell gift for a friend whose family decided to repatriate was met with criticism from one of the professors. However, the class stood its ground. Mr. Władysław Buras, condemned for his communist sympathies, opened the list of those returning to Poland, but later withdrew from the transport. In most cases, the decision to return to the country or remain in emigration depended on family circumstances. Those who had their relatives in Poland, despite their aversion to the imposed regime, often returned. Our close friend, Mrs. Maria Kobordo, with her daughters Halina and Jagoda, lost her husband in Russia, in Kharkov, and the fate of her only son Tadeusz was unknown to her. Those of us who had someone in the Polish army under English command were able to leave for England. My father was in the II Corps with Anders, so apart from us, his closest family, he gave Mrs. Kobordo as his married sister, which gave her the opportunity to leave for England. In the meantime, however, Mrs. Maria received news about her son through the Red Cross, that he was alive and in Poland. So she decided to return to the country, in order to save her son, as a single man, from being drafted into the army, because as the sole guardian of his mother and two underage sisters, he was not threatened by the army.

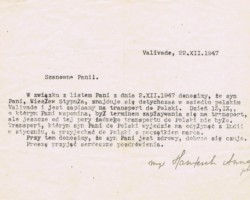

This example is one of the variants of complicated human fates and motives for acting in one way or another. The first list of 25 people who volunteered to return to Poland was sent on October 13, 1945 to Mr. M. Nagar (Assistant Secretary Commonwealth Relations Dept.) by the delegate of the Ministry of Law and Social Policy. Most of the people on the list volunteered to return to Poland with the reservation that they wanted to have answers to certain questions from the government delegate from Warsaw before they made a definite decision. 11 people expressed their willingness to return without reservations (mostly Belarusians and citizens of Ukrainian nationality). The biweekly Polak w Niechciał in India from February 1946 informed us about Molotov’s attacks on General Anders and the II Corps. Supposedly, 100,000 Polish soldiers in Italy were supposed to threaten world peace. The existence of the Polish army abroad was very badly perceived by the Soviets and the Warsaw regime, so their propaganda said that the soldiers would gladly return to the country, if not for the terror of the commanders. England opposed the Russian attacks, mindful of the Poles’ merits during the war, despite the fact that the Polish army was a burden on the British taxpayer and they wanted to avoid irritating Russia. For practical reasons, the English found it convenient to use the Poles for the duties of occupying Italy. However, they hoped that eventually they would be persuaded to return to Poland. In March 1946, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Ernest Bevin, made an appeal to the Polish Armed Forces under British command in the House of Commons in London, in which he urged them to return to Poland. He claims that the British government negotiated with the provisional government in Poland, from which he obtained a statement specifying the conditions for returning to the country. The day after Bevin’s statement, Warsaw radio explained that the Polish government had not announced any new declaration regarding soldiers returning to Poland, and the Rzeczpospolita daily speculates that the British government, impatient with the lack of response from the Polish side, presented a summary of the long-announced terms of return. The Polish government in London protested after Bevin’s declaration against the fact that the British government had decided the fate of the Polish army without even waiting for the decisions made in Yalta concerning Poland to be implemented, because one of the conditions was free elections, which never took place. Most soldiers did not want to return to a country ruled by authorities imposed on citizens, not democratically elected. On March 20, 1946, the Polish Press Agency in Edinburgh expressed disappointment among Polish soldiers who had received an anonymous leaflet without a signature, written in poor Polish, supposedly expressing a declaration of the Warsaw government ensuring a safe return to the country, mostly containing threats regarding offenses against the Polish State. Fortunately, during the discussions on refugees at the UN, the Soviets failed to obtain a decision to deprive the refugees of protection.

Eleanor Roosevelt’s draft resolution was adopted, stating that refugees who “…express legitimate reservations about returning to their countries cannot be forced to do so.” In March 1946, news reached us in the Settlement that the Warsaw Consulate in London had ordered the registration of all Polish citizens in Great Britain, except soldiers on active duty. Registration would mean compliance with the orders of the Warsaw government. This could result in the loss of political refugee rights. In our Settlement, at the beginning of August, a Provisional Repatriation Committee was established, whose task was to inform interested parties about the progress of repatriation matters. One of the pieces of information given by the Committee in the Daily Circular was that “…the transport currently organized, financed by UNRRA, was the only free one. All subsequent efforts will have to be made entirely privately, with the costs covered from one’s own pocket. The expected route from India to Poland by land was to be as follows: India-Egypt-Trieste, or India-Egypt-by sea to Gdynia.” The August issue of the Pole in India from 1946 published a resolution adopted by Polish refugees in connection with the possible arrival of the Warsaw repatriation mission in India: “…The declaration, signed by representatives of all Polish refugee organizations in India and adopted unanimously at a mass meeting of refugees in Valivade – Kolhapur, contains a statement that Polish refugees have not recognized and will never recognize the temporary Warsaw administration, completely wrongly called the Polish government. Polish refugees in India, the declaration continues, like all true Poles in Poland and all over the world, recognize the legal continuity of the Polish State and consider its Head, President W. Raczkiewicz, as the only legitimate and constitutional authority of the Republic of Poland and the Council of Polish Political Parties in London as the only democratic Polish representation. The attitude of Polish refugees in India towards the repatriation mission cannot therefore be positive.” A translation of this declaration was published in the Indian press, in the Times of India and the Bombay Morning Standard. In April 1946, a Polish Repatriation Mission was established at the Polish embassy in Cairo, consisting of 5 people. At the beginning of November, the embassy’s counselor, Marian Ciechanowski, sent urgent letters to citizen minister W. Wolski in Warsaw, writing among other things: “…a candidate for India should be sent to Cairo without delay (he would have to be a person who knows English). In addition, the issue of finances would also have to be quickly settled, which currently looks as follows:

1. The Repatriation Mission is indebted to the Polish Legation in Cairo for the sum of over 600 pounds.

2. This Mission cannot receive any further loans without the prior consent of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

3. In the event of failure to send the funds to the Mission, this Legation will consider itself compelled to recommand the Mission to the Country.”

Evidently, the ‘citizen minister’ took the matter to heart, because in November, Ms. Burakiewicz, a member of the Polish Legation in Cairo, came to Valivade to provide information on living conditions in Poland and to organize the return to the Country of those people who voluntarily wished to go there. She was received in the camp with a great deal of distrust. Her visit was described in the Valivade Chronicle as follows: she stopped at the Valivade stop, on the way to Kolhapur. The delegate took up residence in the residence of the principality of Kolhapur, owned by Colonel Harvey, whose guest she was. Having arrived at the Estate, she toured it in the company of the camp commander, Colonel Neate. The Estate remained stoic. Only those interested, who gathered at the repatriation club, sympathized with her. On November 21 and 22, 1946, registration for departure to Poland was held. A meeting was called for November 25 under the chairmanship of the Resident, the Estate Commander, and a delegate. 135 interested people arrived at the cinema hall. The Resident and the delegate spoke at the meeting. At the end of the month, the date of departure of the first transport to Poland was announced – it falls on December 8 this year. The delegate gave an interview to a correspondent of the Kolhapur press, painting the camp and its inhabitants in the worst possible colors.” In a report to the Polish embassy in Cairo from 16.2.1947, Ms. Burakiewicz wrote that as a result of anti-government propaganda in ‘reactionary’ magazines like Pole in India: “…Everyone is contra and thinks of settling down anywhere, just not in Poland. They are afraid of lower living standards, the NKVD, Siberians, they do not believe that the Polish Government is really Polish, they are convinced that it governs everything and that Russia interferes in everything. They have also been convinced that anyone from present Russian territories will be forcibly resettled there from Poland. In addition, some of them have some criminal or political offences from their time in Russia and they fear legal liability, believing in the existence of Russian governments in Poland… Most women do not decide to return because they are waiting for the decision of their husbands or brothers who are still in England. … The population of the camp is still befuddled by the project of a second Poland somewhere in the world. If not all together, then in large centers with their own administration, their own schools and their own priests. They want to do the same with Russia. They constantly refer to the suffering in Russia, to the famine they suffered there. Finding a common language with these people is impossible.

The desire to possess is the most important, lack of ambition, squeezing out of the English or anyone as much as possible and as much as possible. To these base instincts, an ideology of martyrdom and patriotism is developed. The desire to resettle anywhere in the world is rather grotesque; they throw around geographical names, about which in most cases they have not the slightest idea. …The person who is clearly harming us both in India and in repatriation is Wanda Dynowska. This lady has lived in India for a dozen or so years, adopted the Hindu religion, dresses in Hindu clothing and has the surname Uma Devi. She has great relations with both the English and the Hindus. She belongs to Gandhi’s closer circle, knows Nehru and has relations with the former Polish Jew Frydman, who is a member of the Congress. Uma Devi comes to the camp, gives lectures, drives Polish children around India, making propaganda of Polishness in her understanding. Children ride in Łowicz and Kraków costumes, organizing dances and songs. She often comes to the camp, lives there and has meetings in various committees. When I intervened to ask what this lady was doing in the camp and why she was living there, I was told that she was only involved in cultural and educational activities. He replied that they could stay for a while, but they could not treat India as a place of settlement, that the war had ended two years ago and it was time to go home or settle wherever they would be accepted – there is enough local population in India.”

“The first repatriation transport from Valivade, comprising 154 people, set off on December 8, 1946 in the afternoon. They were loaded into third-class carriages at Valivade station. The carriages were taken to Kolhapur late at night and from there directed to Poona and Bombay, where they were embarked. The repatriates are going by ship to Naples, from where they are to arrive in the country by train.” Aleksandra Czeczeników describes the journey as follows:

“…In Valivade we took a photo of the whole group. We spent Christmas on the ship. In the early morning hours of

January 1, 1947, we sailed into Naples, seeing Vesuvius on the right and the lights of Capri on the left. In the second half of January, the whole group traveled by train to Poland. Our family had to stay in Italy due to the illness and death of my six-year-old brother. After the funeral, we were transported to Bari and joined a group of Poles returning from Africa.” Ola’s family was not the only one who had to be separated from the transport in Italy due to illness. Rena Płocka was travelling from the Red Cross hospital in Bombay after an appendicitis operation. After a long sea and land journey from Naples to the transit camp in Cinecitta near Rome, her stitches burst and she found herself in an Italian hospital, without documents, without the luggage that had been left with the transport. She could not communicate in Polish or English. She was saved by a lucky accident: one day she heard two nuns passing by talking in Polish.

She begged them to inform her about the location of her ‘unknown soldier’, with whom she had been corresponding and who she knew worked in the editorial office of the magazine Parada. The knight came to the rescue: he helped find the documents, stole Rena, married her in St. Peter’s Basilica, and then brought her to England. In the January 1947 issue of Polak w India, the following news was reported: “…In connection with the departure of the repatriate transport, the board of the Union of Poles in India decided to provide warm clothing to children leaving for the country. In response to the Union’s appeal, social organizations contributed a total of 2,113 rupees and 7 annas. The collected sum was spent on purchasing materials and sewing clothes. In addition, each child was provided with money for the journey. All those leaving were also provided with medicines donated by the Delegation of the Society for the Protection of Poles (formerly the Polish Red Cross). As for the second transport of repatriates, the commandant informed those interested that they should be ready from 12th February 1947, so that they could return their heavy luggage at any time. The date of departure has not yet been set.” The second transport finally left on 8th April. Stach Skrzat wrote about it as follows: “…The decision to return to Poland was made after receiving information that father was alive. We left in the second transport in April 1947. I travelled together with Zocha Dudkówna. Mr. Kwiek (brother of the king of Polish Gypsies) also returned with us. On the ship, the English treated us badly, they were haughty.” In February 1947, in Polak w India, an article from the Indian newspaper The Mahratta, written by Syt. Sitram Puranik, was reprinted in English under the title Problem of the Poles in India. Why do they not want to return? in which the author briefly explains the experiences of Poles deported to Russia and the routes they took to get to India, and then gives the reasons why Poles did not want to return to Poland. He goes on to write that complaints and questions are heard as to why India should spend so much on these refugees. He explains that India has never paid anything for Poles. He suggests that Indians should be more interested in Polish culture and art, because then they will see that they have a lot in common with Poles, especially in terms of views on life, so different from the materialistic Western ones and so similar to the Indian ones. In May 1947, we learn from research published by the IRO commission, meeting in London, that the number of applications to return to Poland was growing, that Poles were the largest national group – 335 thousand – among the refugees. It did not happen because people believed that Poland was free and democratic, but the majority of those who claimed that they would never come to terms with communist rule in Poland “are going home today, precisely because their previous decision was based on very fragile foundations: on a naive belief in a third world war, on fear alone, on the illusion that life in emigration would go smoothly,and not on a true understanding of the role of the political emigrant in the fight for human freedom and Polish independence.”

In Valivade, the third transport to Poland was being prepared; the departure was set for May 17. 197 people were leaving, including 56 individuals (mostly elderly people), 52 families and 17 children from a correctional facility. The largest percentage were families of farmers and military settlers. The Valivade Chronicle reports: “…The transport was divided into several smaller groups due to its size and, like the previous one, was loaded in the afternoon at the Valivade stop onto special carriages running with the regular train at that time towards Miraj and Poona. Large crowds of Valivade residents were bidding farewell to their friends, acquaintances and neighbours. The train set off at 5:15 p.m.

As always, this transport was supplied with medicines distributed through the Polish Association in India. It is worth mentioning in this connection that when the repatriates turn to the local ‘repatriation committee’ for help, they only receive a large propaganda load and … advice to knock on the door of the Polish Association in India for material help. This is all the more amusing because later the Association will receive its usual share of insults in the national press, when the current leaders of the transport speak out about their merits in the campaign to combat the alleged anti-repatriation campaign in the estate. In 1947, about 75 letters from Poland arrived daily. These letters circulated around the estate and were widely commented on. Most of them were written cautiously, mainly about family and housing matters, avoiding sensitive topics. However, sometimes bold letters were also sent, written bluntly. An excerpt from a letter from the province. Lublin reprinted in Polaku w India from May 24, 1947. “…In Poland, nothing is done better; they promise us and promise us and do nothing. You are lucky that you even got there. You miss your people, your country, of course, but you have to suffer through it… Whoever came from the American or English zone, everyone regrets it, but you can’t go back.” A student who returned from India to Poland wrote to her friend: “…You are happy that you are learning, that you are there. I regret that I left India, I was stupid that I didn’t stay. I feel very funny in my new surroundings; everything is foreign and strange to me. People sometimes talk to people, but uncertainly, because there are people here. I am in Poland, which I missed so much, but it is not what it should be and what it used to be. The land is the same, the trees, the flowers, everything is wonderful, but it’s all in chains. I’ve seen a few Soviets, the order is also Soviet, in general everything is Soviet imitation. I don’t go to school, I’ll probably only go for vocational training… They say that repatriates have priority, but when it comes to dealing with something, they don’t show it. You have to come and get nervous and nothing comes of it…

Everyone asks what it’s like abroad, and I tell them everything. I say openly how they imagine Poland and why they don’t want to come back. Anyone who is smart will agree with me that there’s no point in coming back…”

On July 1, the fourth transport to Poland set off from Valivade, consisting of 53 people. Among those leaving was the former district governor of the estate, Roman Dusza. This fact caused great surprise in the estate, although the former district governor justified his decision with his health condition.

The school inspector Zdzisław Żerebecki and the head of the orphanage Felicja Wierzchowska also left, leaving important posts. The transport set off from Bombay on July 2. In the Polaku w India of July 12, 1947, an article was published under the title: Emigracja a Kraj, reprinted from Polonia Zagraniczna no. 40, from which we learn that official propaganda sometimes presents emigrants “…as lords with pockets full of money, who are not eager to accept a difficult fate and work. Sometimes again as fascists who do not return out of fear of democratic justice. Then again we are victims of foreign capital that wants to use us in the role of white blacks. There are different versions, but no one has dared to give and will not give the honest, true version to the Country. They are trying to impose the conviction on the public that this emigration is already something absolutely foreign to the Country, something that has strayed onto a wrong side track, while in the Country there is supposedly a strong current of reform and progressivity. Each member of the emigration is more or less aware of this tendency to set him against his own nation. But the dilemma, the quarrel and the conflict exist only on the surface and are the result of artificial procedures. There is no such conflict inside. The emigration feels, thinks and reacts together with the nation. This strange phenomenon of spiritual unity from time to time manifests itself in some fact. It happened recently in the face of the threat to the Recovered Territories, which after centuries of foreign rule returned to the Motherland.” In January 1948, there was another transport to Poland, in which scout Hanka Handerek left. Helena Szafrańska described it as follows: “…From the first days of January, we started packing intensively. We also helped scout Hanka. We, in turn, were helped by Jasiek and Bronek Siedleccy, who were still waiting for transport to England. On January 16, 1946, I wrote in my diary: We are going! I am very happy. The apartment is pitifully empty. We are giving away things we no longer need to Indian children, we are giving one of the Indian women to look after our cat. On January 17, we left. The girls from my squad came to the wagon with a bouquet of flowers. On January 18, we were loaded onto a ship in Bombay. It was a large transport ship, the Georgic. It was crowded on board, because there were many English and American soldiers returning to their countries. In the evening, we organized a scout fireplace on board. I wrote in my diary that it was a success.

On the night of 19-20 January the ship left port. We sailed through the Arabian Sea and the Red Sea to Port Said. Here 40 Polish soldiers and about 1,000 English soldiers returning home boarded the ship. On 30 January the ship arrived in Naples. Here in the port I saw for the first time in five years a begging, crippled, white child. Shock! Europe! While unloading our luggage it turned out that some of it had gone missing somewhere, but the IRO representative assured us that the lost items would be found and sent back to Poland. After leaving the ship we were loaded onto freight cars waiting on the tracks. With cigarettes brought from India we bought oranges and apples. On 1 February the train set off for Rome. The closer we got to Rome, the more we noticed the greyness of the landscape, the poverty of the people and the ruins of buildings. The nightmare of the recently passed war loomed on every side. In Rome the train stopped at the Roma-Prestina station where we were given a piece of bread with meat and a mug of milk each. There we waited for the train to Poland. At that time the Polish consul visited us, he spoke about the financial difficulties in Poland and what was worth buying in Italy and taking with us to our homeland. On February 4th we saw a Polish medical train from Krakow at the station. I looked at it carefully right away and read all the signs. Only the eagle without a crown was an unpleasant surprise. In the afternoon we moved to the Polish train. The carriages had two rows of triple bunks inside. We settled down on them. The next day we were organized to visit Rome. In four hours, even driving a car (truck) we could only superficially get to know the architecture of this beautiful city, but it was still a great experience for me. By the time we left our hand luggage had increased by a box of oranges and lemons, a packet of figs and raisins. We also received dry provisions for the journey. In the evening, Jews from the IRO camp joined our transport, and during the night, repatriates from Africa. On February 7, we left Rome. In the evening, we passed Florence. On the 8th, we crossed the Alps. Apart from looking at the landscapes we passed, we diversified our journey by talking, reading, and playing cards. At night, we crossed Tyrol, and on February 9, Bavaria, and at noon we entered the borders of Czechoslovakia. We reached the Polish border on February 10. We were given hot coffee from the kitchen, soup at noon, and tea in the evening. There was an iron stove in the wagon, so it was warm and we could heat canned meat. In the evening, we arrived in Zebrzydowice, and the next day around noon, the transport reached Koźle, where we were placed in a repatriate camp. Above the gate was a sign: THE HOMELAND WELCOMES YOU. It was nice, but some of the residents of Koźle we met asked with surprise why we had returned from abroad. We were assigned a small room, the duty room, because the other rooms were occupied.

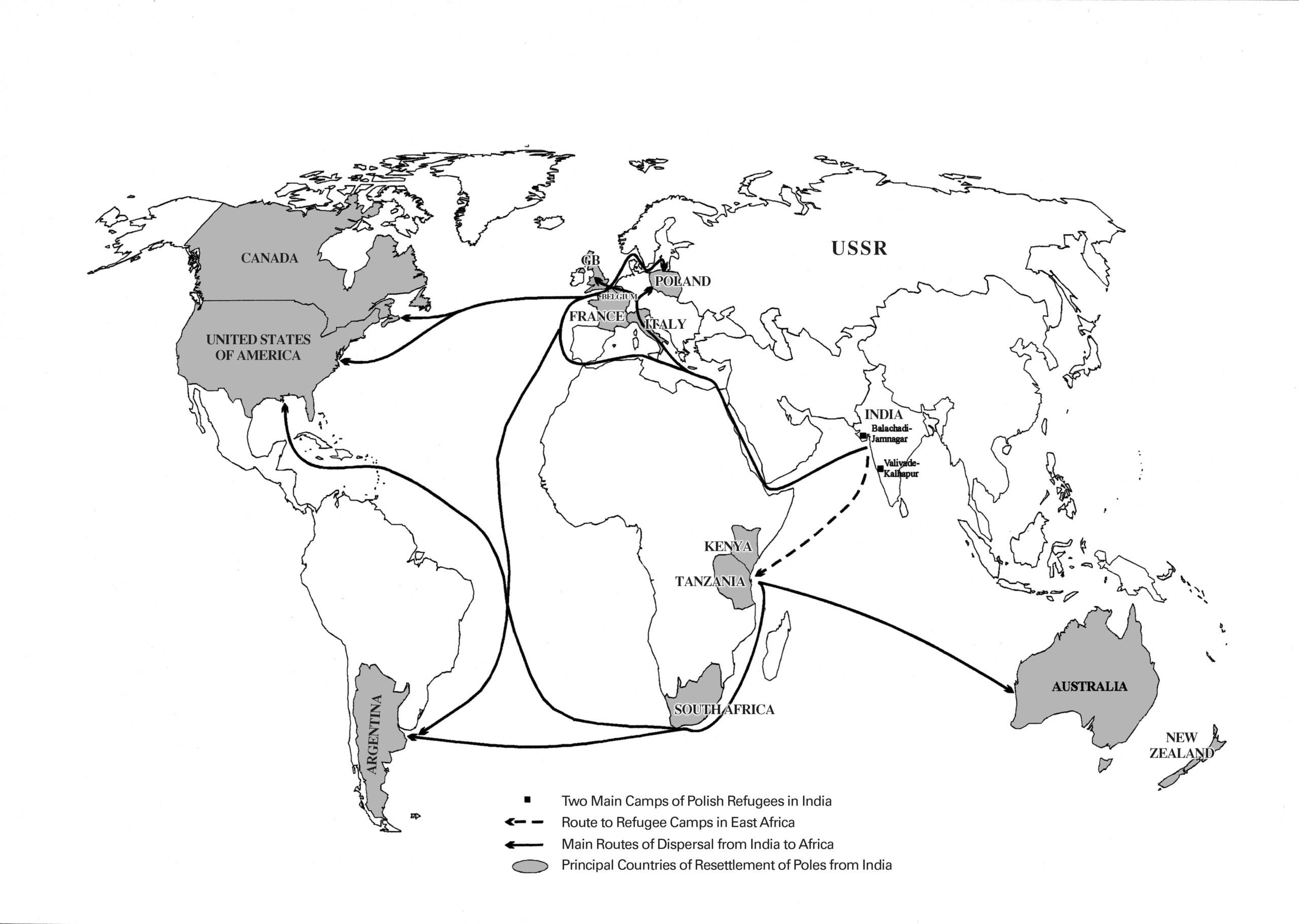

We moved in together with Sister Hanka. The camp administration, fearing that we might have brought cholera, ordered mandatory tests, vaccinations and a two-week quarantine. On February 14, a journalist from Trybuna Robotnicza visited the camp. He spoke to Sister Hanka; he was interested in where we had come from. Leszek Trzaska’s diary shows that the last group of repatriates left the Osiedle in February 1948, together with those who were leaving for East Africa. “…Departure from Valivade on February 22, embarkation on the military transport ship General MB Stuart. Route: Mombasa (March 8), where some of the Valivadeans disembarked and a fairly large group of Poles from African camps joined, then through the Suez Canal (Port Said on March 17) to Genoa (March 21). Here the transport was divided into two groups: those who were returning to Poland and those who were going to Germany, from where further departures into the world were to take place. Those returning to Poland left Genoa on 27th March on a Polish PCK train, crossed the border in Międzylesie and reached Dziedzice-Czechowice for the repatriation assembly point, from where the departure to Poland took place. However, the percentage of the population of the Valivade settlement deciding to repatriate in all these transports to Poland was negligible; only 473 people left. Most of the inhabitants decided to take on the difficult role of political emigrants, 9so in time they settled not only in Great Britain, but also in South American countries, Australia, New Zealand, the United States, Canada, and some also remained in the former centres of their refugee residence – next to Australia, also in Mexico and Africa), in the conviction that they would be better able to serve the Polish cause outside the borders of the country, reminding at every opportunity that there is no truly free Poland.