A Land Born in Battle

As a result of the partitions, the Polish Republic was wiped off the map of Europe. Despite numerous national uprisings Poles did not manage to regain independence – not until a worldwide conflict involved all the partitioning powers, the deposition of the Tsar by the February Revolution and the subsequent October Revolution in Russia, the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, created conditions suitable for the restoration of the Polish state. This unique opportunity was exploited by Józef Piłsudski, who was born in Żułów near Wilno. Shortly after an unsuccessful revolt in 1905, he promoted the thesis that combat against the enemy should be conducted using one’s own army. In the years preceding the outbreak of the First World War, under the slogan of armed struggle for Independence, he created the military cadres of the future Polish Legions (Związek Walki Czynnej/Association for Active Struggle, Związek Strzelecki /Rifleman Association, “Strzelec”/”Rifleman” Society). Leading them, he realized the dream of millions of Poles, a free and independent Polish state.

As a result of the partitions, the Polish Republic was wiped off the map of Europe. Despite numerous national uprisings Poles did not manage to regain independence – not until a worldwide conflict involved all the partitioning powers, the deposition of the Tsar by the February Revolution and the subsequent October Revolution in Russia, the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, created conditions suitable for the restoration of the Polish state. This unique opportunity was exploited by Józef Piłsudski, who was born in Żułów near Wilno. Shortly after an unsuccessful revolt in 1905, he promoted the thesis that combat against the enemy should be conducted using one’s own army. In the years preceding the outbreak of the First World War, under the slogan of armed struggle for Independence, he created the military cadres of the future Polish Legions (Związek Walki Czynnej/Association for Active Struggle, Związek Strzelecki /Rifleman Association, “Strzelec”/”Rifleman” Society). Leading them, he realized the dream of millions of Poles, a free and independent Polish state.

The battle for an independent Poland started in September 1914 with the entry of the First Cadre Rifle Company into the area of the Russian Partition of Poland. This effort, aimed at triggering an anti-Russian uprising in the Polish Kingdom, failed due to lack of popular support. Józef Piłsudski then subordinated himself to the Supreme National Committee (Naczelny Komitet Narodowy) and began the formation of the Polish Legions, composed of three brigades. Simultaneously, he set up the Polish Military Organization, whose aim was to cause a diversion within the territory of the Russian partition. The brigades took part in fighting on many fronts during the war. The First Brigade, personally led by Józef Piłsudski, operated near Krakow and in the Russian partition, involved in the battles of the Nida, Krzywopłoty, Łowiczówek, Konary, Jastków and Kamionka in the Lublin region, and the Rasna and Wysokie Litewskie in the Podlasie region. The Second Brigade, led by Ferdynand Kuttner, fought in the Eastern Carpathians, where it was involved in the battle of Mołotkowo, and later in the battles of Zielona, Rafajłowa and Kirlibaba. Its second regiment of Uhlans was involved in the famous charge of Rokitna in the Bukowina. The Third Brigade, led in turn by Wiktor Krzesicki, Stanisław Szeptycki, Zygmunt Zieliński and Bolesław Roj, entered the battle in July of 1915 and cooperated with Józef Piłsudski’s brigade in the Lublin region.

Starting in October all three brigades were positioned on the Wołynia front. This was the peak of combat activity of the Polish Legions, which numbered over 16 thousand soldiers. In July of 1916 Polish troops took part in the battles of river Styr, where they fought the largest battle in their history – Kostiuchnowka. In that battle the legionaries, despite the hurricane-like gunfire and constant Russian attacks, maintained the front line for several days. They withdrew only after the collapse of their flank defences, which had been protected by Hungarian and Czech troops.

When the Russian front reached Galicia, the Central Powers, experiencing ever more acute shortages of manpower, encouraged the Poles to fight them. On November 5, 1916, the emperors of Germany and Austria-Hungary issued a decree pronouncing that the lands of the Russian partition of Poland will create a sovereign Polish State after the Great War – a state that would be permanently allied with the Central Powers. It was the first visible effect of the military buildup engineered by Józef Piłsudski.

Another breakthrough was provided by the February Revolution in Russia in 1917. This turn of events enabled a wider range of activities for Poles in Russia. Efforts were initiated to form separate divisions which could join the struggle for independence. In April of 1917 the Fourth Division of Polish Rifles was formed in the East. In July the First Polish Corps (one out of the three) was assembled, led by Józef Dowbor-Musnicki. Finally, in June a Polish Army in France (called the “Blue Army”) was beginning to form, eventually led by Józef Haller. When the Poles had finally acquired their own armed forces, the Central Powers demanded that the Polish units swear an oath of allegiance. Józef Piłsudski thought that, after the expulsion of the Russians from the lands of the soon-to-be-restored Polish Republic, further support from the Germans and Austrians would not serve the Polish national interest. Accordingly, he and the First and the Third Brigades refused to give a slavish oath, triggering the so called “oath crisis”. As a consequence, both brigades were disbanded. Some officers were interned in the Benjaminowo camp, while the rest of the soldiers were interned in Szczypiorno. Józef Piłsudski was interned in the Magdeburg prison.

Due to the deteriorating situation on the Western Front, the Central Powers began to lose control over the occupied Polish lands as well as the Regent Council, or state government. On October 7, 1918 the Regent Council issued a manifesto to the Polish Nation, formulating the principle of the independence of the Republic. It was the first act of the Polish government declaring restoration of statehood. Throughout the area of the former partitions, spontaneous disarming of the withdrawing German troops had begun. During the night of the 6th and 7th of November, the Temporary People’s Government of the Second Republic of Poland was formed in Lublin, headed by Ignacy Daszyński. It stabilized the situation in a country swept by chaos. At the moment of cessation of hostilities, which coincided with the release of Józef Piłsudski and his return to Warsaw on the night of November 10, 1918, the question of Polish independence was already obvious.

When the four-year war ended on November 11th, the Regent Council entrusted Józef Piłsudski with supreme military command, and on November 14th the Regent Council dissolved itself, transferring its power to Piłsudski.

One of the most important tasks facing the newly forming Polish State was a determination of its territorial extent. The first decisions in that matter were taken during a conference organized in 1919 in Versailles near Paris. Leaders of the 27 victorious nations gathered there to establish principles for a lasting peace and to decide the fate of the defeated. On October 28, 1919 a peace treaty with Germany was signed, establishing the Polish western border. Germany lost almost the entirety of Greater Poland (Wielkopolska), a region which won its independence in an armed struggle even before the peace negotiations started. The Second Polish Republic was also granted the East Pomerania region, but without Gdansk, which received a Free City status and remained administered by the League of Nations. The Versailles Treaty also called for plebiscites in Upper Silesia, Warmia and Masuria to determine if these regions would belong to Poland.

The issue of the eastern border was diametrically different. The position of the Entente Powers with regards to the place of Poland in the East lacked consistency. On one hand an expansion of Bolshevism was feared, on the other hand a diminution of Russian territorial holdings by Poland was not welcome. In this situation it became obvious that the shape of the eastern border had to be decided politically, but primarily by a military force. A majority of Poles considered the pre-partitions lands a natural part of the historical and national legacy. They did not take into account the new realities ensuing from the century-old policies of Russian and Austrian occupants, leading to far-reaching changes in the Polish situation in the Kresy (Eastern Borderlands). In political circles, discussions on the future of the eastern lands, which were to be retaken by Polish troops, led to two fundamental concepts: Federation (authored by Piłsudski) and Incorporation (authored by Roman Dmowski, Piłsudski’s political opponent, but a man with undisputed contributions to the establishment of the independent Polish State). Neither of these concepts was acceptable to the leaders of the Bolshevik “Red” or counterrevolutionary “White” Russia. All of them treated the reborn Poland as a part of the former Russian Empire. In the opinion of the “Whites” – Poland, separating Russia from the rest of Europe, violated the principles of a Russian policy established by Peter I and Catherina II. The “Reds”, in turn, expressed a view that securing the achievements of the revolution and the formation of a new society within a single Bolshevik state is impossible. The necessary condition to maintain the achievements of the October Revolution was to transfer the socialist ideals to the West. Poland, separating Russia from the working class centers of Germany, Czechoslovakia or Hungary, had to disappear.

However, the struggle for the eastern border of Poland did not begin with an armed conflict with Bolshevik Russia, but rather an armed conflict with a hastily-formed Eastern Ukrainian People’s Republic. The situation in that region was extremely variable and complicated. Three separate centers were attempting to simultaneously create Ukrainian statehood: the Eastern Ukrainian People’s Republic in Eastern Galicia, the Ukrainian People’s Republic governed by a Directorate with Semen Petlura, and the Ukrainian Socialist Soviet Republic. The first two centers fought with the third and with the troops of the “White” generals. Polish-Ukrainian relationships were particularly strained by the dispute about Lwów (Lviv), where Poles constituted the ethnic majority. On one hand, the city was one of the most dynamic centers of Polish culture; on the other hand, it was the main center of Ukrainian nationalism. Lwów was the only city with a Ukrainian university. The struggle began on November 1, 1918 when Austro-Hungarian soldiers of Ukrainian descent occupied the majority of public buildings in Lwów and proclaimed a formation of the Eastern Ukrainian People’s Republic. This move was opposed by Polish underground organizations and Polish inhabitants of the city, including young people later named “Orlęta Lwowskie” (Lwów Eaglets). Their forces were later supported by the emerging Polish Army. The first stage of this conflict ended during the night of November 22/23, 1918 when the troops of the Ukrainian Halicz Army withdrew from Lwów and begun a siege of the city. On May 22, 1919 the Polish Army offensive routed the enemy forces from the city. Over the following months, battles for Eastern Galicia continued. From the spring of 1919, thanks in part to the deployment of the Haller’s “Blue” Army to the Ukrainian front, the forces of the Eastern Ukrainian People’s Republic were systematically pushed east. By the middle of July the government of the Republic, with the remnants of their army, was pushed beyond the river Zbrucz. A formal armistice, sanctioning Polish territorial holdings, was signed on September 1, 1919. On November 21st the Supreme Council of the peace conference confirmed the autonomous status of Eastern Galicia. Poland received a mandate from the League of Nations to administer this area for 25 years. In March of 1923, Eastern Galicia was finally recognized internationally as an integral part of the re-born Polish State.

Russia disliked the Polish offensive, which at one point reached Kiev and ended in the occupation of that city. In a response to the Polish army taking Wilno, Minsk and Lwów, the Bolshevik army mounted a counteroffensive. The troops’ march was accompanied by murder and violence against civilians. Within the first months of the fighting, Soviets occupied a part of the historical Polish Kresy as far as Kamieniec Podolski. In the following few months Polish troops were pushed South West, as the Bolsheviks reached the rivers Bug and Narew. In July of 1920 the Bolshevik troops took Wilno, Grodno and Białystok, and one month later – Łomża and Ostrołęka. The Soviets begun to pose a threat to the capital, when the “Miracle on the Vistula” took place. This heroic struggle and the victory of Poles over the troops of Mikhail Tukhachevsky during the battle of Warsaw, secured the newly regained independence and protected Europe from the danger of the expansion of the Bolshevik revolution to the West.

In the middle of August a group led by Józef Piłsudski attacked the enemy from beyond the river Wieprz. This group broke the frontline at Kock, took Podlasie and appeared at the rear of the Tukhachevski’s forces. The Soviet troops, attacked from the South and the West, were forced to withdraw. The Bolshevik forces in Southern Poland also experienced defeat. After the battles of Komarów and Hrubieszów, which culminated in the destruction of the 1st Cavalry Division of Semyon Budyonny, the enemy retreated. By mid-October the Polish Army reached the Tarnopol-Dubno-Minsk-Dryssa line. On October 12, 1920 an armistice treaty was signed, and on October 18th the hostilities ceased.

In the shadow of the conflict with Bolshevik Russia, a Polish-Lithuanian feud flared up. In the Polish national conscience the traditions of the Union of Lublin were still alive. However, the leaders of the reviving Lithuanian State did not see a possibility of a closer union with the Second Polish Republic. A trigger point was the issue of Wilno and the Wilno Region. The historical capital of Lithuania was for a long time a city with Polish character, a fact that was difficult to accept by the Lithuanians who demanded its incorporation into their own state. During the chase behind the retreating Bolsheviks, Polish troops entered the territory contested with Lithuania. According to the earlier-signed Bolshevik-Lithuanian treaty, Wilno was supposed to belong to Lithuania and the Lithuanians strongly objected to a plebiscite to decide on the status of the Wilno Region. Taking this into account, Józef Piłsudski commanded General Lucjan Żeligowski to simulate a mutiny and to enter Wilno with his armed forces. On October 9, 1920 the 1st Lithuanian-Byelorussian Division, existing in the structures of the Polish Army and composed in large part of soldiers hailing from the contested region, expelled Lithuanians from the city. On this occupied territory, a new state was formed – Central Lithuania. On January 8, 1922 elections to the local parliament were held, which then unanimously voted for the incorporation of Wilno and its environs with Poland.

The official end to hostilities in the East took part on March 18, 1921 with a signing of a peace treaty in Riga by the Second Polish Republic, the Russian Federation and the Ukrainian Soviet Republics (both appearing as official parties in the conflict). The document primarily specified the border between Poland and Russia: running from the river Dzwina in the North, through Byelorussia (except Minsk which stayed on the Soviet side), marshes of the Polesie, all the way to the rivers Zbrucz and Dniester. Both parties guaranteed mutual rights in the areas of culture, education, and religious freedoms for the Polish, Russian and Ukrainian minorities across the respective borders. In addition, Poland was supposed to receive the cultural collections plundered and taken away after 1772, and to be compensated 30 million gold rubles for the economical exploitation of the Polish Kingdom by the Russian government in 19th century.

The period of struggle for the eastern borders of Poland was unusually turbulent for the Eastern Borderlands. The border set by the Riga Treaty did not provide for the return of all pre-partition lands of the First Polish Republic. As a result, many families identifying themselves with Poland – e.g. in the area of Kamieniec Podolski, which did not return to the motherland and belonged to the Soviet side – had to remain under foreign rule. For many of these families it was a great tragedy. However, for the Poles remaining in Russia the most tragic fate was yet to come. The Soviet government soon formed the Polish Autonomous Districts – Marchlewszczyzna (on the territory of the Ukrainian SSR) and Dzierzyńszczyzna (on the territory of the Byelorussian SSR). They were abolished in the 1930′s and a massive deportation of Poles to Siberia and Kazakhstan followed. Simultaneously with the loss of the pseudo-autonomy of these Polish districts, mass executions of Poles in the USSR began (the, so called, Polish operation of the NKVD). Only those that managed to immigrate to Poland from the lands remaining beyond the eastern border after the Riga Treaty avoided persecution. They numbered about 100 thousand, mostly noble landowners and intelligentsia.

At the birth of the Second Polish Republic the Eastern Borderlands constituted a civilizational backwater compared to the western and central parts of the country. This situation become even worse after the war of 1920-21, when the civilian and industrial infrastructure spared by World War I was further destroyed, along with crops and livestock. This led to the depopulation of some of the eastern administrative units (powiats). Under such conditions the independent Polish Republic had to undertake suitable steps to consolidate the eastern regions with the rest of the Polish lands. An important issue in these Eastern Borderlands was the national minorities whose rights were guaranteed by a “little Versailles Treaty” from June of 1919. Additionally, in 1922 the Polish Parliament decided, in the autonomy statute for the provinces of Lwów, Stanisławow and Tarnopol, that their regional councils will be composed of two chambers, i.e. Polish and Ruthenian. Similarly, there was to be no Polish colonization in these provinces and a Ukrainian University was to be formed in Lwów.

At the birth of the Second Polish Republic the Eastern Borderlands constituted a civilizational backwater compared to the western and central parts of the country. This situation become even worse after the war of 1920-21, when the civilian and industrial infrastructure spared by World War I was further destroyed, along with crops and livestock. This led to the depopulation of some of the eastern administrative units (powiats). Under such conditions the independent Polish Republic had to undertake suitable steps to consolidate the eastern regions with the rest of the Polish lands. An important issue in these Eastern Borderlands was the national minorities whose rights were guaranteed by a “little Versailles Treaty” from June of 1919. Additionally, in 1922 the Polish Parliament decided, in the autonomy statute for the provinces of Lwów, Stanisławow and Tarnopol, that their regional councils will be composed of two chambers, i.e. Polish and Ruthenian. Similarly, there was to be no Polish colonization in these provinces and a Ukrainian University was to be formed in Lwów.

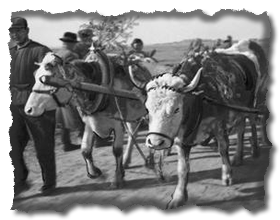

As the Second Republic of Poland was being born, it quickly became obvious that the builders of Polish statehood had to contend with not only the problem of defending the newly-attained independence of their homeland, but also the problem of uniting the geographic regions, diverse in many ways, into one economic entity. Each of the provinces was at varying levels of economic development, had different currencies, and had different social and ethnic structures. In particular, there was a large disproportion in the numbers of landowners between Western and Central Poland and the Eastern Borderlands, where large industry was almost non-existent. It is important to note that some of the exiting factories and plants had been dismantled and transported east by the Russians. Other factories were destroyed during the Polish-Bolshevik War in 1920. Consequently, the Eastern Borderlands were not only proportionately less industrialized, poorer and less advanced economically; they were also impacted by war. Not only was industry affected, but so was agriculture. For example, during the war in 1920, it was not possible to cultivate more than 3.5 million hectares of land in the Eastern Borderlands. In total, 1.7 million buildings in the Polish countryside were destroyed, 75% of which were agricultural buildings. It was estimated that 456 agricultural buildings were destroyed in a part of the province of Wilno. To that, one must add the slaughter or confiscation of livestock by military units, particularly cattle and pigs. The destruction of whole areas of the countryside deprived the population of infrastructures such as drainage systems, which were indispensable to cultivation.

As the Second Republic of Poland was being born, it quickly became obvious that the builders of Polish statehood had to contend with not only the problem of defending the newly-attained independence of their homeland, but also the problem of uniting the geographic regions, diverse in many ways, into one economic entity. Each of the provinces was at varying levels of economic development, had different currencies, and had different social and ethnic structures. In particular, there was a large disproportion in the numbers of landowners between Western and Central Poland and the Eastern Borderlands, where large industry was almost non-existent. It is important to note that some of the exiting factories and plants had been dismantled and transported east by the Russians. Other factories were destroyed during the Polish-Bolshevik War in 1920. Consequently, the Eastern Borderlands were not only proportionately less industrialized, poorer and less advanced economically; they were also impacted by war. Not only was industry affected, but so was agriculture. For example, during the war in 1920, it was not possible to cultivate more than 3.5 million hectares of land in the Eastern Borderlands. In total, 1.7 million buildings in the Polish countryside were destroyed, 75% of which were agricultural buildings. It was estimated that 456 agricultural buildings were destroyed in a part of the province of Wilno. To that, one must add the slaughter or confiscation of livestock by military units, particularly cattle and pigs. The destruction of whole areas of the countryside deprived the population of infrastructures such as drainage systems, which were indispensable to cultivation.

The Riga Peace Treaty, confirmed by the Ambassadors’ Council, defined the borders of the Second Republic – 25.5% of these, or 1412km, bordered Soviet Russia. The borders with Lithuania, Latvia and Romania were significantly shorter.

The Riga Peace Treaty, confirmed by the Ambassadors’ Council, defined the borders of the Second Republic – 25.5% of these, or 1412km, bordered Soviet Russia. The borders with Lithuania, Latvia and Romania were significantly shorter.

Social & Cultural Life

Much depended on the active participation of the two largest centers of the Kresy region: Lwow and Wilno. Their influence would radiate to the provincial communities. Libraries, museums, theatres, galleries, social organizations were established. But, above all, the schools of higher education allowed for an expanded knowledge of world culture in the smaller centers of the region.

The most modern form of disseminating education and culture to the widest audience at that time was radio. The first broadcast of Polish radio in the Kresy region occurred in Wilno on January 15, 1928. It broadcast at a distance of 140 km, and by 1938 it sent into the ether almost 5000 hours of broadcast time. Two years after the Wilno station was established, a second, very popular station in Lwow was activated on January 15, 1930 with similar broadcast capabilities. Few remember the fact that a newer third station was activated in July, 1938 a year before the war in Baranowicze and it broadcast a distance of 120 km. At that time in the province of Nowogrod there were 11 radios for a population of 1000. The province of Wilno had 26 radios and the province of Lvov had 28 radios as compared to the national average of 29 radios. Unfortunately, the radio station in Luck was still under construction when WWII started. The most popular country-wide satirical show was “Funny Radio Waves From Lwow”. Other popular radio programs were “Our Eye”, “Happy Sunday,” “Ta-joj,” and “City Hall Conversations with the Lions.” Kresy radio stations broadcast satirical, sport and musical programs similar to current broadcasts, as well as foreign programs. Author interviews from Lwow and Wilno were broadcast nationwide.

The Press was particularly important to this mass mandate. In 1937 there were 163 periodicals in the Kresy provinces, of which 17 were dailies and 29 were weeklies. This was minimal in comparison to the western provinces where 609 titles were published, of which there were 62 dailies and 128 weeklies. The most important was Wilno’s “Slowo” appearing from 1811. Also important was “Gazeta Lwowska” published in Lwow from 1894 – 1934 and “Slowo Polskie,” “Gazeta Codzienna” (1908-1939), “Dziennik Ludowy,” “Kurier Lwowski,” “Wiek Nowy” and the nationally syndicated “Chwila” (1919-1939). Both Lwow and Wilno editions of “Rzeczpospolitej” were available. In Grodno there was also the publication “Echo Grodzienskie”.

Popular pre-war amusements were movie theatres. In 1929 there were 727 movie theatres in the Second Polish Republic. In the provinces Lwow had 63, Wilno 17, Wolyn 23 and there were only 9 in Poleski. Not all of them had sound capabilities. Three years before the war 69 of the 75 movie theatres in Lwow province had sound capabilities. By 1939 there were no remaining silent movie theatres in the Kresy area.

In the short period of the evolution of the Second Polish Republic many museums were either opened or expanded in the Kresy area. In April 1939, 48 museums existed in the Kresy provinces, of which 17 were in Lwow (in comparison Warsaw had 30.) There were 26 museums in the vicinity of Lwow province. That number includes 4 museums in Wilno and 1 in the entire Poleskie area. Nowogrod province had 3 museums, Wolyn 5, Stanislawow 3 and Tarnopol 6. The biggest and most popular belonged to Lwow. There was the “Galeria Narodowa” of the city of Lwow, “The Museum Dzieduszyckich” found in the eastern marketplace, “The Panorama Raclawicka,” “The Historical Museum of the City of Lwow”, “The Lubomirski Museum,” “The King John III national museum” and also in Wilno “The Museum of the Organization of Friends of Education.”

Whoever wanted to read Polish could take advantage of books in the self-serve libraries and popular reading rooms run by social organizations. Of the pre-1939 libraries established in Lwow province, where there were 15 permanent ones and 28 mobile ones. In Wilno there were significantly more, 79 permanent libraries and 485 mobile ones; similarly in Nowogrod there were 69 permanent ones and 651 mobile ones. There were fewer self-governing libraries in the southern Kresy region compared to Wilno and Nowogrod. The proportion was reversed when taking into account social libraries. Lwow had 1604 permanent ones and 919 mobile ones. Similar numbers existed in Tarnopol and Stanislawow.

In addition, many theatres were founded in the Kresy region. From the moment freedom was gained, theatres grew in fame and in the consciousness of the public. Two years before WWII 503,000 tickets were sold in theatres in Lwow alone. The number in Wilno was 311,000. Decidedly fewer tickets were sold in that time period for concerts and literary readings. In Lwow that number was around 15,000.

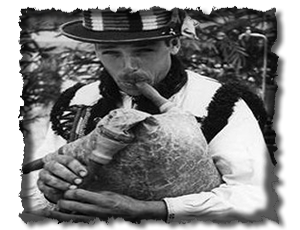

In the countryside, there were many popular forms of entertainment: folk choirs, folk revues and light box plays. For example, in the Wilno region in 1939 there were 523 theatrical groups and 190 choirs. In the vicinity of Lwow there were 2394 light box groups, 1141 theatres and 666 folk choirs. The most famous Kresy theatre was at Pohulanka in Wilno. Located on Wielka Pohulanka street it was graced by the performances of Hanka Ordonowna, Aleksander Zelwerowicz, Igor Przegrodski, Hanka Bielicka, Danuta Szaflarska and Zbigniew Blichewicz. In the 1920’s the director was Juliusz Osterwa. He arrived with his review “Reduta” in 1925. Similar great theatre occurred in the beautiful “Teatr Wielki” in Lwow. The stage was graced, among others, by the performance of Helena Modrzejewska and Aleksander Zabczynski. The director of the theatre from 1930 was Leon Schiller.

An important role, particularly in the Kresy region, was played by numerous public societal organizations and educational-cultural ones located in both cities and the countryside. They fulfilled functions of social life similar to that of the libraries and reading rooms. Among others they were the “Polish Maternity School,” “Society of Popular Schools”, “Society of the Workers University”, “Catholic Union of Young Females”, “Central Union of Country Youth”, “ Society of Country Youth RP Wici”, “Central Organizational Circle of Country Landlords,” Rifleman’s Union,” “Union of Young Christians,” “Polish YMCA,” “Polish Red Cross,” “Air and Anti-gas Defensive League,” “Polish Boy Scouts and Polish Girl Scouts,” “Building Society of General Schools,” “Friends of Academic Youth Society,” “Fire Fighter’s Society”. In 1936 alone there were 314 active educational societies in Poland of which 17 were in Wilno and 38 in Lwow. Some of these organizations are still active today e.g. the YMCA and Polish Scouting.

Sport was another area in which Kresy residents met each other. Kresy sport clubs had an impressive effect on the expansion of sport in the Second Polish Republic. The oldest sports club was “Pogon Lwow, founded in 1904 in conjunction with High School IV in Lwow. It functioned under the official name of “Lwow Sports Club-Pogon Lwow”. Taking into account the history of Polish soccer after “Lechii Lwow” and “Czarnych Lwow” this was the third soccer organization during the time period of the Second Polish Republic to be a four-time Polish Champion. In the 1930’s, the Army sports club named “Smigly Wilno” comprised of the Wilno Garrison Officers, was part of the Premiere Polish Soccer League. Other notable clubs were “AZS Wilno” and “AZS Lwow” known for, among other things, their very good ice hockey clubs. The most popular sport was soccer which, towards the end of the Second Polish Republic, had over124, 000 soccer players in clubs. There were also 23,000 skiers, 13,000 hand-ball players, 22,000 sport shooters and 9,000 in light athletics. Many people were part of the popular physical education Gymnasium Union “SOKOL”, which had approximately 50,000 members in almost 832 clubs within the Second Polish Republic.

The Kresy region also yielded many well-known creative writers, which we currently do not identify with either Lwow, Wilno or other Kresy locations. Among others, it is important to name Kornel Makuszynski ( 1884 – 1953 ), writer and poet born in Stryj , author of “Panna z mokra glowa”, “O Dwoch takich, co ukradli ksiezyc”, “Szatana z siodmej klasy” and “Awantury o Basie”. He did not return to a free Lwow in 1918 but settled in Warsaw, however, his writing skills were strengthened thanks to a degree in Philology at the University of Lwow and his initial editorial work in the Kresy region. Leopold Staff, born in Lwow (1878-1957) was a famous poet whose road in life was similar to Kornel Makuszynski. He belonged to the “Moda Polska” generation. His creativity earned him an iconic position in twentieth century Polish literature. He developed as a writer in Lwow thanks to the education he gained at “V Gimnazjum Klasycznym” and most of all at the University of Lwow, where he was a triple major. Leopold Staff was part of a literary group named “Planetnikow”. They met at a villa named “Zaswiecie” located near the Ossolineum in Lwow. Another famous member of the group was Jan Kasprowicz (1860-1926), dramatist and poet. Although he was born beyond the Kresy region, he is closely identified with the Lwow bohemian artist community. Born, raised and educated in Lwow was the writer Jan Parandowski (1895-1978) known for his ancient culture writings. Wilno produced a distinguished Conservative Publicist named Stanislaw Cat-Mackiewicz (1896-1966). He was the founder of the popular Wilno periodical “Slowo”. The author of “Dewajtis” and Wrzosu”, Maria Rodziewiczowna, was born in Pieniuchach na Grodzienszczyznie. A few kilometers from Kiejdan, in a shtetl, the Nobel Prize winner Czeslaw Milosz (1911-2004) was born. He was a student at the Stefan Batory University in Wilno, a poet of the Zagary group and, prior to 1939, an employee of Wilno Polish radio station. It must be noted that all of the above passed away beyond the Kresy region: Makuszynski and Kasprowicz in Zakopane, Milosz in Krakow, Parandowski in Warsaw, Rodziewiczowna in Leonowie pod Skierniewicami and Staff in Skarzysku-Kamiennej.

It is also important to mention popular actors Szczepcia and Toncia. Something must be said about the characters hidden under these pseudonyms. The first was born in Lwow as Kazimierz Wajda (1905-1955). He was a graduate of schools in Lwow and a student of the Polytechnic. Toncio Tonko was Henryk Vogelfanger (1904-1990), who was also born in Lwow and studied law at the John Kazimierz University. Both became popular because of the radio program “ Funny Radio Waves From Lwow”. They wrote scripts for Wiktor Budzynski and also for themselves. This was the first cabaret broadcast by Polish radio outside Warsaw. Their work was so excellent that it was the most popular radio program in the Second Polish Republic and was heard by six million listeners. They were also not allowed to stay in their beloved Lwow after 1945. They both passed away in Warsaw. It is interesting to note that many important Polish cultural figures were educated at the “III Gimnazjum Meskiego im. Stefan Batory” located directly across from the Lwow Polish Radio Station.

Among the many famous creative individuals born in Lwow was the poet and dramatist Zbigniew Herbert (1924-1998), poet Adam Zagajewski (1945- ), writer and satirist Janusz Wasylkowski (1933- ), actor and director Adam Hanuszkiewicz ( 1924- ), director Jerzy Passendorfer (1923-2003), actor Ryszard Ronczewski (1930- ), poet Teodor Bujnicki (1907-1944), violinist Jascha Heifetz (1901-1987). Born in other Kresy areas: director Jerzy Kawalerowicz (1922-2007) born in Gwozdzcu in the vicinity of Kolomyi, director Jerzy Janicki (1928-2007) born in podoskim Czortkowie, and the popular actor Zygmunt Kestowicz (1921-2007) from the Wilno region.

At the end of WWII Poland lost the Kresy region, with its abundance of culture manifested in its museums, theatres, and libraries. Yet, in spite of this cataclysm, thousands of creative individuals raised and educated in the Kresy region were saved and subsequently introduced in post-war Poland; this is an immeasurable gift to the benefit of the country. For many years, in spite of domestic difficulties and overwhelming poverty, Polish nationalism has been maintained by the Poles living in the pre-war Kresy areas, where theatres, clubs, libraries, groups, etc. have remained locations for maintaining Polish heritage. These accomplishments are still visible today.