The historic city of Vilnius

Czesław Miłosz

„May the souls of the departed leave us in peace”

There are not many cities in Europe that have been subjected to as much mythology as Vilnius. By this I mean, stories taken from the past that are not necessarily related to fact. The history of this city is so strange that it borders on the realm of fairy tales, which it frequently has done, and these tales have changed depending on who was doing the telling: Lithuanians, Poles, Jews, Byelorussians, etc.

Whenever I visit Vilnius I always have the impression that one must walk there like on thin ice, and that it does not suffice to be a person, because one is immediately asked if one is Lithuanian, Polish, Jewish, or German, as though the gloomy 20th century – the age of ethnic divisions – continued here unabated.

Prior to 1939, Polish Vilnius and Jewish Vilnius lived side by side, although there was little communication between the two; they were, in effect, two cities and two cultures. To Poles, Vilnius is still the cradle of Romanticism – the most important movement in Polish history – whose significance goes beyond literature.

The city also had great meaning in Lithuanian history. Without exaggerating one can say that Lithuania, as the mythical land of ancient forests and pagan gods, influenced the imaginations of Polish writers, especially those of the Romantic period. In the sixteenth century, Maciej Stryjkowski published his giant Lithuanian Chronicle, which served as a reference for his followers for centuries. The Lithuanian national identity was formed as a result of such literary works as Mickiewicz’s Grażyna and Konrad Wallenrod , Mindowe by Slowacki, Pojata, daughter of Lidia by Feliks Bernatowicz, or even the curious lengthy poem Witolorauda by Józef Ignatius Kraszewski, published in 1840, which contains a litany of Lithuanian pagan gods who act like ancient Greek gods. Another series that has a Romantic pedigree are the nine volumes of The Ancient History of the Lithuanian People by Narbutta that appeared in Vilnius between 1837 and 1841. In Polish literature, the pagan Lithuania of mythology fulfilled the same role as ancient Scottish mythology did in British literature.

The fact that Lithuanian national consciousness was influenced by Romantic ideas also had an effect on Lithuanian historians, who tend to idealize certain rulers and magnates of the past.

The beauty of the surroundings, as well as the architecture of this city has a kind of magic within it. It makes one forget that one is standing on the graves of approximately 100,000 Jews. The horror of this mass murder is a constant here, though it is easier for the living not to dwell on it. For Jewish historians, Vilnius remains the “Jerusalem of the North” – one of the most important centres of Jewish culture in the world. Growing up in Polish Vilnius, I did not know much of the Jewish past of the city, which shows how the nationalist textbooks of the time simply eliminated certain facts. For instance, what happened here in 1749 was unpleasant for Polish Catholicism, and therefore was erased from history books. Count Valentin Potocki, accused of being a heretic, was burned alive. While he was a student in Amsterdam he had converted to Judaism and, even under torture, refused to reconvert to Christianity. To my total ignorance, the tomb of this martyr of the Jewish faith was treated with great veneration by Vilnius Jews. In a way, I could serve as an example of how a mind can be deformed by a nationalistic education. In later years, it took a great deal of effort for me to reverse this mindset. Consequently, I warn today’s Lithuanian youth that they must avoid being subjected to a new deformation of the mind, this time a Lithuanian one.

In conclusion, I want to show how difficult it is to penetrate the truth, if it is someone else’s truth. There is a painting, by a painter from Vilnius that I find very moving. The painter, Ludomir Ślendziński, was one of the most famous Vilnius painters of the interwar period. For a time he was an art teacher in my school and later had his own studio at the university. He was born in Vilnius and was the son of an artistic dynasty – both his father and grandfather had been painters. On leaving Vilnius in 1945, Ślendzinski painted a rather mythical portrait of the city as a fairy-like spectacle of church towers and clouds. He named this painting Oratorium. The painting can be found in the Ślendziński Gallery In Bialystok. Personally, I would call Oratorium a hymn to the beauty of Vilnius’s architecture, as well as a hymn of grief – the lament of an exile that will remain part of the history of the city, even when no one remembers who the victors were, and who the vanquished.

On October 2nd, 1999, through the efforts of the Goethe Institute and the Polish Institute, Gůnter Grass, Czesław Miłosz, Wisława Szymborska and Tomas Venclova, appeared in Vilnius. The notes above are fragments of Czeslaw Milosz’s speech.

Source: Official internet web site of Czeslaw Milosz www.milosz.pl

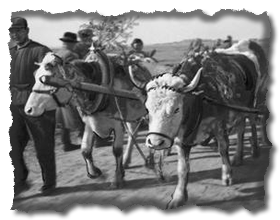

At the birth of the Second Polish Republic the Eastern Borderlands constituted a civilizational backwater compared to the western and central parts of the country. This situation become even worse after the war of 1920-21, when the civilian and industrial infrastructure spared by World War I was further destroyed, along with crops and livestock. This led to the depopulation of some of the eastern administrative units (powiats). Under such conditions the independent Polish Republic had to undertake suitable steps to consolidate the eastern regions with the rest of the Polish lands. An important issue in these Eastern Borderlands was the national minorities whose rights were guaranteed by a “little Versailles Treaty” from June of 1919. Additionally, in 1922 the Polish Parliament decided, in the autonomy statute for the provinces of Lwów, Stanisławow and Tarnopol, that their regional councils will be composed of two chambers, i.e. Polish and Ruthenian. Similarly, there was to be no Polish colonization in these provinces and a Ukrainian University was to be formed in Lwów.

At the birth of the Second Polish Republic the Eastern Borderlands constituted a civilizational backwater compared to the western and central parts of the country. This situation become even worse after the war of 1920-21, when the civilian and industrial infrastructure spared by World War I was further destroyed, along with crops and livestock. This led to the depopulation of some of the eastern administrative units (powiats). Under such conditions the independent Polish Republic had to undertake suitable steps to consolidate the eastern regions with the rest of the Polish lands. An important issue in these Eastern Borderlands was the national minorities whose rights were guaranteed by a “little Versailles Treaty” from June of 1919. Additionally, in 1922 the Polish Parliament decided, in the autonomy statute for the provinces of Lwów, Stanisławow and Tarnopol, that their regional councils will be composed of two chambers, i.e. Polish and Ruthenian. Similarly, there was to be no Polish colonization in these provinces and a Ukrainian University was to be formed in Lwów.

As the Second Republic of Poland was being born, it quickly became obvious that the builders of Polish statehood had to contend with not only the problem of defending the newly-attained independence of their homeland, but also the problem of uniting the geographic regions, diverse in many ways, into one economic entity. Each of the provinces was at varying levels of economic development, had different currencies, and had different social and ethnic structures. In particular, there was a large disproportion in the numbers of landowners between Western and Central Poland and the Eastern Borderlands, where large industry was almost non-existent. It is important to note that some of the exiting factories and plants had been dismantled and transported east by the Russians. Other factories were destroyed during the Polish-Bolshevik War in 1920. Consequently, the Eastern Borderlands were not only proportionately less industrialized, poorer and less advanced economically; they were also impacted by war. Not only was industry affected, but so was agriculture. For example, during the war in 1920, it was not possible to cultivate more than 3.5 million hectares of land in the Eastern Borderlands. In total, 1.7 million buildings in the Polish countryside were destroyed, 75% of which were agricultural buildings. It was estimated that 456 agricultural buildings were destroyed in a part of the province of Wilno. To that, one must add the slaughter or confiscation of livestock by military units, particularly cattle and pigs. The destruction of whole areas of the countryside deprived the population of infrastructures such as drainage systems, which were indispensable to cultivation.

As the Second Republic of Poland was being born, it quickly became obvious that the builders of Polish statehood had to contend with not only the problem of defending the newly-attained independence of their homeland, but also the problem of uniting the geographic regions, diverse in many ways, into one economic entity. Each of the provinces was at varying levels of economic development, had different currencies, and had different social and ethnic structures. In particular, there was a large disproportion in the numbers of landowners between Western and Central Poland and the Eastern Borderlands, where large industry was almost non-existent. It is important to note that some of the exiting factories and plants had been dismantled and transported east by the Russians. Other factories were destroyed during the Polish-Bolshevik War in 1920. Consequently, the Eastern Borderlands were not only proportionately less industrialized, poorer and less advanced economically; they were also impacted by war. Not only was industry affected, but so was agriculture. For example, during the war in 1920, it was not possible to cultivate more than 3.5 million hectares of land in the Eastern Borderlands. In total, 1.7 million buildings in the Polish countryside were destroyed, 75% of which were agricultural buildings. It was estimated that 456 agricultural buildings were destroyed in a part of the province of Wilno. To that, one must add the slaughter or confiscation of livestock by military units, particularly cattle and pigs. The destruction of whole areas of the countryside deprived the population of infrastructures such as drainage systems, which were indispensable to cultivation.

The Riga Peace Treaty, confirmed by the Ambassadors’ Council, defined the borders of the Second Republic – 25.5% of these, or 1412km, bordered Soviet Russia. The borders with Lithuania, Latvia and Romania were significantly shorter.

The Riga Peace Treaty, confirmed by the Ambassadors’ Council, defined the borders of the Second Republic – 25.5% of these, or 1412km, bordered Soviet Russia. The borders with Lithuania, Latvia and Romania were significantly shorter.

Social & Cultural Life

Much depended on the active participation of the two largest centers of the Kresy region: Lwow and Wilno. Their influence would radiate to the provincial communities. Libraries, museums, theatres, galleries, social organizations were established. But, above all, the schools of higher education allowed for an expanded knowledge of world culture in the smaller centers of the region.

The most modern form of disseminating education and culture to the widest audience at that time was radio. The first broadcast of Polish radio in the Kresy region occurred in Wilno on January 15, 1928. It broadcast at a distance of 140 km, and by 1938 it sent into the ether almost 5000 hours of broadcast time. Two years after the Wilno station was established, a second, very popular station in Lwow was activated on January 15, 1930 with similar broadcast capabilities. Few remember the fact that a newer third station was activated in July, 1938 a year before the war in Baranowicze and it broadcast a distance of 120 km. At that time in the province of Nowogrod there were 11 radios for a population of 1000. The province of Wilno had 26 radios and the province of Lvov had 28 radios as compared to the national average of 29 radios. Unfortunately, the radio station in Luck was still under construction when WWII started. The most popular country-wide satirical show was “Funny Radio Waves From Lwow”. Other popular radio programs were “Our Eye”, “Happy Sunday,” “Ta-joj,” and “City Hall Conversations with the Lions.” Kresy radio stations broadcast satirical, sport and musical programs similar to current broadcasts, as well as foreign programs. Author interviews from Lwow and Wilno were broadcast nationwide.

The Press was particularly important to this mass mandate. In 1937 there were 163 periodicals in the Kresy provinces, of which 17 were dailies and 29 were weeklies. This was minimal in comparison to the western provinces where 609 titles were published, of which there were 62 dailies and 128 weeklies. The most important was Wilno’s “Slowo” appearing from 1811. Also important was “Gazeta Lwowska” published in Lwow from 1894 – 1934 and “Slowo Polskie,” “Gazeta Codzienna” (1908-1939), “Dziennik Ludowy,” “Kurier Lwowski,” “Wiek Nowy” and the nationally syndicated “Chwila” (1919-1939). Both Lwow and Wilno editions of “Rzeczpospolitej” were available. In Grodno there was also the publication “Echo Grodzienskie”.

Popular pre-war amusements were movie theatres. In 1929 there were 727 movie theatres in the Second Polish Republic. In the provinces Lwow had 63, Wilno 17, Wolyn 23 and there were only 9 in Poleski. Not all of them had sound capabilities. Three years before the war 69 of the 75 movie theatres in Lwow province had sound capabilities. By 1939 there were no remaining silent movie theatres in the Kresy area.

In the short period of the evolution of the Second Polish Republic many museums were either opened or expanded in the Kresy area. In April 1939, 48 museums existed in the Kresy provinces, of which 17 were in Lwow (in comparison Warsaw had 30.) There were 26 museums in the vicinity of Lwow province. That number includes 4 museums in Wilno and 1 in the entire Poleskie area. Nowogrod province had 3 museums, Wolyn 5, Stanislawow 3 and Tarnopol 6. The biggest and most popular belonged to Lwow. There was the “Galeria Narodowa” of the city of Lwow, “The Museum Dzieduszyckich” found in the eastern marketplace, “The Panorama Raclawicka,” “The Historical Museum of the City of Lwow”, “The Lubomirski Museum,” “The King John III national museum” and also in Wilno “The Museum of the Organization of Friends of Education.”

Whoever wanted to read Polish could take advantage of books in the self-serve libraries and popular reading rooms run by social organizations. Of the pre-1939 libraries established in Lwow province, where there were 15 permanent ones and 28 mobile ones. In Wilno there were significantly more, 79 permanent libraries and 485 mobile ones; similarly in Nowogrod there were 69 permanent ones and 651 mobile ones. There were fewer self-governing libraries in the southern Kresy region compared to Wilno and Nowogrod. The proportion was reversed when taking into account social libraries. Lwow had 1604 permanent ones and 919 mobile ones. Similar numbers existed in Tarnopol and Stanislawow.

In addition, many theatres were founded in the Kresy region. From the moment freedom was gained, theatres grew in fame and in the consciousness of the public. Two years before WWII 503,000 tickets were sold in theatres in Lwow alone. The number in Wilno was 311,000. Decidedly fewer tickets were sold in that time period for concerts and literary readings. In Lwow that number was around 15,000.

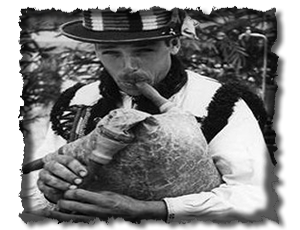

In the countryside, there were many popular forms of entertainment: folk choirs, folk revues and light box plays. For example, in the Wilno region in 1939 there were 523 theatrical groups and 190 choirs. In the vicinity of Lwow there were 2394 light box groups, 1141 theatres and 666 folk choirs. The most famous Kresy theatre was at Pohulanka in Wilno. Located on Wielka Pohulanka street it was graced by the performances of Hanka Ordonowna, Aleksander Zelwerowicz, Igor Przegrodski, Hanka Bielicka, Danuta Szaflarska and Zbigniew Blichewicz. In the 1920’s the director was Juliusz Osterwa. He arrived with his review “Reduta” in 1925. Similar great theatre occurred in the beautiful “Teatr Wielki” in Lwow. The stage was graced, among others, by the performance of Helena Modrzejewska and Aleksander Zabczynski. The director of the theatre from 1930 was Leon Schiller.

An important role, particularly in the Kresy region, was played by numerous public societal organizations and educational-cultural ones located in both cities and the countryside. They fulfilled functions of social life similar to that of the libraries and reading rooms. Among others they were the “Polish Maternity School,” “Society of Popular Schools”, “Society of the Workers University”, “Catholic Union of Young Females”, “Central Union of Country Youth”, “ Society of Country Youth RP Wici”, “Central Organizational Circle of Country Landlords,” Rifleman’s Union,” “Union of Young Christians,” “Polish YMCA,” “Polish Red Cross,” “Air and Anti-gas Defensive League,” “Polish Boy Scouts and Polish Girl Scouts,” “Building Society of General Schools,” “Friends of Academic Youth Society,” “Fire Fighter’s Society”. In 1936 alone there were 314 active educational societies in Poland of which 17 were in Wilno and 38 in Lwow. Some of these organizations are still active today e.g. the YMCA and Polish Scouting.

Sport was another area in which Kresy residents met each other. Kresy sport clubs had an impressive effect on the expansion of sport in the Second Polish Republic. The oldest sports club was “Pogon Lwow, founded in 1904 in conjunction with High School IV in Lwow. It functioned under the official name of “Lwow Sports Club-Pogon Lwow”. Taking into account the history of Polish soccer after “Lechii Lwow” and “Czarnych Lwow” this was the third soccer organization during the time period of the Second Polish Republic to be a four-time Polish Champion. In the 1930’s, the Army sports club named “Smigly Wilno” comprised of the Wilno Garrison Officers, was part of the Premiere Polish Soccer League. Other notable clubs were “AZS Wilno” and “AZS Lwow” known for, among other things, their very good ice hockey clubs. The most popular sport was soccer which, towards the end of the Second Polish Republic, had over124, 000 soccer players in clubs. There were also 23,000 skiers, 13,000 hand-ball players, 22,000 sport shooters and 9,000 in light athletics. Many people were part of the popular physical education Gymnasium Union “SOKOL”, which had approximately 50,000 members in almost 832 clubs within the Second Polish Republic.

The Kresy region also yielded many well-known creative writers, which we currently do not identify with either Lwow, Wilno or other Kresy locations. Among others, it is important to name Kornel Makuszynski ( 1884 – 1953 ), writer and poet born in Stryj , author of “Panna z mokra glowa”, “O Dwoch takich, co ukradli ksiezyc”, “Szatana z siodmej klasy” and “Awantury o Basie”. He did not return to a free Lwow in 1918 but settled in Warsaw, however, his writing skills were strengthened thanks to a degree in Philology at the University of Lwow and his initial editorial work in the Kresy region. Leopold Staff, born in Lwow (1878-1957) was a famous poet whose road in life was similar to Kornel Makuszynski. He belonged to the “Moda Polska” generation. His creativity earned him an iconic position in twentieth century Polish literature. He developed as a writer in Lwow thanks to the education he gained at “V Gimnazjum Klasycznym” and most of all at the University of Lwow, where he was a triple major. Leopold Staff was part of a literary group named “Planetnikow”. They met at a villa named “Zaswiecie” located near the Ossolineum in Lwow. Another famous member of the group was Jan Kasprowicz (1860-1926), dramatist and poet. Although he was born beyond the Kresy region, he is closely identified with the Lwow bohemian artist community. Born, raised and educated in Lwow was the writer Jan Parandowski (1895-1978) known for his ancient culture writings. Wilno produced a distinguished Conservative Publicist named Stanislaw Cat-Mackiewicz (1896-1966). He was the founder of the popular Wilno periodical “Slowo”. The author of “Dewajtis” and Wrzosu”, Maria Rodziewiczowna, was born in Pieniuchach na Grodzienszczyznie. A few kilometers from Kiejdan, in a shtetl, the Nobel Prize winner Czeslaw Milosz (1911-2004) was born. He was a student at the Stefan Batory University in Wilno, a poet of the Zagary group and, prior to 1939, an employee of Wilno Polish radio station. It must be noted that all of the above passed away beyond the Kresy region: Makuszynski and Kasprowicz in Zakopane, Milosz in Krakow, Parandowski in Warsaw, Rodziewiczowna in Leonowie pod Skierniewicami and Staff in Skarzysku-Kamiennej.

It is also important to mention popular actors Szczepcia and Toncia. Something must be said about the characters hidden under these pseudonyms. The first was born in Lwow as Kazimierz Wajda (1905-1955). He was a graduate of schools in Lwow and a student of the Polytechnic. Toncio Tonko was Henryk Vogelfanger (1904-1990), who was also born in Lwow and studied law at the John Kazimierz University. Both became popular because of the radio program “ Funny Radio Waves From Lwow”. They wrote scripts for Wiktor Budzynski and also for themselves. This was the first cabaret broadcast by Polish radio outside Warsaw. Their work was so excellent that it was the most popular radio program in the Second Polish Republic and was heard by six million listeners. They were also not allowed to stay in their beloved Lwow after 1945. They both passed away in Warsaw. It is interesting to note that many important Polish cultural figures were educated at the “III Gimnazjum Meskiego im. Stefan Batory” located directly across from the Lwow Polish Radio Station.

Among the many famous creative individuals born in Lwow was the poet and dramatist Zbigniew Herbert (1924-1998), poet Adam Zagajewski (1945- ), writer and satirist Janusz Wasylkowski (1933- ), actor and director Adam Hanuszkiewicz ( 1924- ), director Jerzy Passendorfer (1923-2003), actor Ryszard Ronczewski (1930- ), poet Teodor Bujnicki (1907-1944), violinist Jascha Heifetz (1901-1987). Born in other Kresy areas: director Jerzy Kawalerowicz (1922-2007) born in Gwozdzcu in the vicinity of Kolomyi, director Jerzy Janicki (1928-2007) born in podoskim Czortkowie, and the popular actor Zygmunt Kestowicz (1921-2007) from the Wilno region.

At the end of WWII Poland lost the Kresy region, with its abundance of culture manifested in its museums, theatres, and libraries. Yet, in spite of this cataclysm, thousands of creative individuals raised and educated in the Kresy region were saved and subsequently introduced in post-war Poland; this is an immeasurable gift to the benefit of the country. For many years, in spite of domestic difficulties and overwhelming poverty, Polish nationalism has been maintained by the Poles living in the pre-war Kresy areas, where theatres, clubs, libraries, groups, etc. have remained locations for maintaining Polish heritage. These accomplishments are still visible today.