Quick Links

Main Polish Refugee Settlements in India

Polish refugee camps in India were organised by the Polish Delegation of the Ministry of Labour and Social Welfare under the leadership of Wiktor Styburski, delegate in the period 29 May – 30 October 1943, and Kira Banasińska, deputy delegate of the Ministry of Labour and Social Welfare (also after Styburski’s departure).

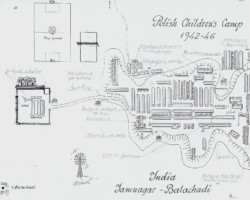

A housing estate for Polish children in Balachadi

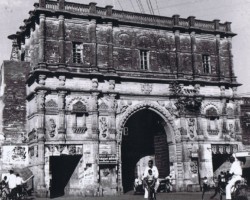

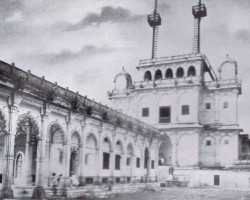

The settlement for Polish children in Balachadi was the first permanent, large centre built specifically for evacuees from the Soviet Union. It was located near the seaside, summer residence of Maharaja Digvijaysinhji on the Kathiawar peninsula, near the small village of Balachadi near the city of Jamnagar. It was the capital of the principality of Nawanagar, and at the same time the seat of the Maharaja – in a huge princely palace. About 25 km northwest of Jamnagar, on a seaside rock, was his summer residence, hidden in the thicket of a small but very rich in terms of flora park and orchard complex. Along the sandy beach, on low flat dunes, stretched a low strip of lush greenery dominated by acacias, agaves and small cacti, as well as sharp seaside grass. Among this greenery, carefully maintained golf courses shone through. Further on stretched a semi-desert landscape, characteristic of this region of India. It was diversified by numerous low, stony hills, covered with sparse grass vegetation and partly with thorny bushes or large cacti. On one of these hills was located a settlement of Polish children, about 1.5 km from the village of Balachadi (for some time the settlement was also called Kiranagar – the prefix kira- came from the name of Kira Banasińska from the Polish Red Cross Delegation in Bombay, an advocate and co-organizer of car expeditions that brought Polish children from the Soviet Union to India; the ending -nagar is quite common in India in the names of larger and smaller towns and literally means a city).

Balachadi was then a small but very old settlement, situated on the route of eternal pilgrimages to the mythical Dwarka. The village consisted of several dozen residential buildings, the remains of an old defensive wall and a partially ruined observation and defensive stone tower. Right next to the settlement was a small, temporary, shallow reservoir, in which fresh water was collected during the summer monsoons. This reservoir, as it later turned out, became a great bane of the Polish settlement… The village population was engaged in farming and breeding cattle, goats and sheep. Contrary to appearances, the very stony soil, originating from weathered volcanic tuffs, was fertile, although it required a lot of work to cultivate it.

However, thanks to their industriousness, the inhabitants of Balachadi were provided with quite bearable living conditions, as for the Indian conditions of that time. Nevertheless, during the construction of the Polish settlement (and later, after its settlement), a dozen or so inhabitants from the surrounding villages found temporary or permanent employment there.

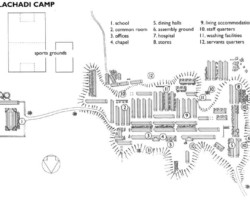

The project of the estate, which could accommodate about 800 people at one time (at one time there were from about 600 to about 800 children there, but due to rotation the number of those who passed through Balachadi was about 1000) was prepared in April 1942 by JO Jagus – the chief engineer of the principality of Nawanagar, in which the estate was located (and which was managed by the aforementioned maharaja). The construction was supervised by an Englishman – Major Geoffrey Clarke, the personal secretary of Maharaja Digvijaysinhji. The implementation was carried out at a lightning pace, because the first transport of children settled in the apartment blocks most probably already on 16 July 1942 (apart from the youngest refugees reaching Balachadi in three car transports of the Bombay Polish Red Cross sent for them to the territory of the USSR, the estate was also inhabited by children who arrived there later, in smaller groups). In principle, the age limits of refugees staying in Balachadi were between two and about 15 years old (those who were adolescents and over that age were moved to the settlement in Valivade); adults could stay there as long as they performed specific care, educational or service functions for children.

The estate consisted of several dozen stone-built buildings in the form of elongated barracks covered with ceramic roof tiles, without floors or ceilings. A single residential block could accommodate about 30 children. The blocks intended for adults were divided into small, individual apartments. The estate also included general utility buildings: a school, hospital, chapel, office, kitchen, dining rooms, community centers, warehouses, craft workshops and rooms for Hindu staff. The estate was not electrified and did not have a sewage system. The collective toilets and bathrooms were located on its outskirts. Water was pumped from a local underground intake to two huge, concrete expansion tanks located directly in the estate. Communication with the nearby city of Jamnagar and the maharaja’s residence was provided by a specially constructed telephone line.

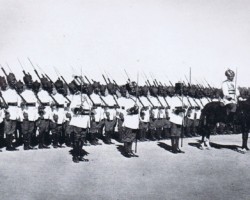

Shortly after the arrival of the second transport of Polish children (in early autumn 1942), all structures enabling its residents to function almost normally were launched in the estate. There was a school and a kindergarten, a hospital, a kitchen, a laundry… The organisation was at a high level – the order services began their work, and a food supply contract was also signed. The management of the estate, acting as the commandant throughout its existence, was carried out by the military chaplain Fr. Franciszek Pluta.

The management functions of the individual departments were performed by Poles (and these were – apart from the separately functioning commandant’s office, school and sanitary facilities, the following departments or rather sections: extracurricular education, cultural-educational and sports, economic-food, uniforms – sub-division of the movables warehouse), while supervision over the budget on behalf of the Indian government was performed by a liaison officer. Initially, this function was performed by an Englishwoman Catherine Clarke, and after her death – by her husband Geoffrey. Apart from the Polish staff, over half of the employees employed in the estate were Indians. Regardless of the official organizational structures, the dominant role in the functioning of the estate, throughout its existence, was played by its great protector Maharaja Digvijaysinhji.

At the same time as the administration was developing, cultural, educational and sports activities were initiated, scouting structures were established and numerous contacts with the local community were established. The youth developed the areas situated between the individual blocks with greenery, which gave the estate the character of a small Polish town, where – incidentally – the national flag was raised every morning. In this way, a small piece of Indian land became a “small homeland” for Polish children for over four years. And despite the subtropical climate and spartan living conditions, in the memory of almost all the pupils from the Balachadi estate, this place remained extremely friendly – also due to the enormous cordiality that was met there on a daily basis by the natives – and held in great sentiment. The estate was officially closed at the end of November 1946 – the children who had been living there until then were moved to the estate in Valivade – the largest centre for Poles in India.

VALIVADE – the largest centre for Poles in India

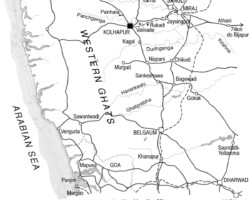

The choice of location for a permanent, larger settlement was primarily guided by a climate suitable for Europeans, access to adequate water, and the ability to feed several thousand people. The British, in agreement with the Polish authorities, decided to build a camp for 5,000 people, women and children, on the Deccan plateau in the principality of Kolhapur, about 300 miles south of Bombay. There, the Panchganga River could supply 50,000 gallons of water daily. The central authorities in Delhi undertook to supply a larger amount of grain and flour to the Poles, so as not to reduce local requirements.

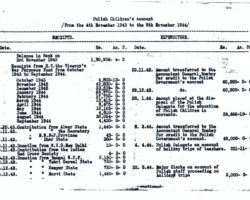

The construction of the estate was entrusted to a construction company, Hindustan Construction Co. The cost of building the estate and maintaining the residents was borne by the Polish Government in London from loans taken from the English Government of His Royal Majesty until the withdrawal of recognition of the Government on 6 July 1945. After the end of the war, UNRRA (United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration) financed refugees until 1947, then IRO (International Refugee Organisation) in the years 1947-1951.

Construction was completed in mid-1943. The camp was expected to be in use for 3 years. In fact, Poles lived there for 5 years – until 1948. However, even now, in the 21st century, it serves refugees from Sind and still exists under the name Gandhinagar. The railway station, Valivade Halt, provided rail access to the settlement.

Valivade was a substitute for a Polish town, with its own administration headed by a starost.

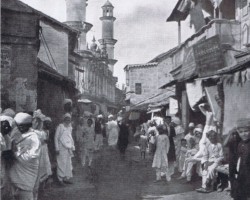

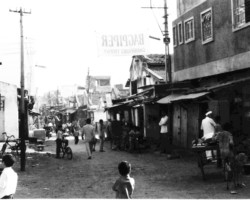

The starosty based its activity on the “Statute of the Settlement and Regulations for Polish Refugees in India”. There was a church, community centres, five elementary schools, a general secondary school and a merchant secondary school, a humanistic and pedagogical secondary school, a post office, a theatre, a cinema, craft workshops, and the Zgoda cooperative. On the outskirts of the camp – Hindu shops and stalls.

The estate consisted of 5 districts. The apartment blocks were divided into 10 separate apartments, without a ceiling or floor, consisting of 2 rooms and a kitchen. The walls were woven from bamboo mats, the roofs were covered with red tiles. To stiffen the floor, Indian women smeared it with a mixture of cow dung and clay. Water had to be carried in buckets from the waterworks. This was usually done by Indians, balancing the buckets on a koromysl. The apartments were equipped with beds with mosquito nets (they protected not only from mosquitoes, but also from various lizards and other amphibians that often fell from the roof) and a solid table, under which one could hide when roof tiles flew on one’s head during a pre-monsoon storm. In the stoves with an iron stove, charcoal was burned. Outside the barracks there were verandas covered with morning glory providing shade and decorated with banana and papaya bushes.

These separate, private apartments were very important for people who, after the cruel experiences in Soviet Russia and many months of “barracks” life in transit camps, could heal the stress associated with the loss or disappearance of their families.

For those with lung problems, treatment was available in the mountain sanatorium in Panchgani. Young people regained their physical fitness by participating in sports – there were courts for playing volleyball and football.

An important element in shaping and hardening the youth was scouting: camps on the edge of the jungle, courses, trips, acquiring skills.

The estate included an orphanage – the General Władysław Sikorski Educational Facility. It consisted of 14 blocks, almost each with two dormitories, each with 35 beds for children, with a room for a teacher in the middle of each building.

The hospital was an important public utility building. The main hospital building was built of split stone, roofed with tiles, with a cloister and a cement floor. Initially, the hospital had 10 wards, which housed a general outpatient clinic, a dental clinic and a pharmacy. Then there was a waiting room, two corridors, three bathrooms with showers and three toilets. The patients were housed in four buildings, with a total of 16 wards and 170 beds. The wards were spacious and bright. The hospital blocks were built like the blocks of individual rooms – with terraces, but unlike the residential ones, they had a cement floor. There were also two buildings made of split stone with a cement floor next to the hospital – one for a morgue, the other for a garage. Of all the buildings on the estate, only the main hospital building had glazed windows. Interestingly, the school buildings, community centers, chapel, theater hall, brick, two-family houses did not have mat curtains (like all other buildings), but window frames made of canvas.

Bathrooms, toilets and laundry facilities were shared. The lighting in the collective and individual rooms was paraffin. In addition, the estate had a post office, a police station occupied by the Indian police, a main material warehouse and two blocks occupied by the offices of the estate administration, the School Inspectorate, the office of the Liaison Officer and the Refugee Committee. In one of these blocks there were four guest rooms with attached brick bathrooms (there were 12 other guest rooms in the estate).

There were nine school buildings in the estate; each contained six classrooms. Their walls were made of mats, which meant that neighboring classrooms interfered with each other during lessons. The floor was made of dirt. In one of the school buildings, four classrooms were converted into a chapel. The altar, steps to the altar and the place for the choir were made of split stone, the floor was cement. The chapel could accommodate about 500 people; it also had a tower added and was modestly but aesthetically furnished. In time, a church was built in the estate.

Teachers tried to keep a vivid image of Poland in the minds of the youth and made them describe Polish landscapes and customs. Priests – Fr. Dallinger and J. Przybysz provided pastoral care to the residents and the liturgical year was strictly observed.

Religious organizations such as the Marian Sodality and altar boys’ groups also developed. All national and religious holidays were celebrated solemnly. Classical plays were performed in the theater. In community centers, the lack of a sufficient number of books was compensated for by reading aloud. Courses for the illiterate allowed people in need to write letters to their loved ones in the army and to read. Shared war experiences evened out pre-war class divisions and the settlement was completely egalitarian: officers’ wives lived next to privates or peasant women in complete harmony.

The housewives tried to match local products to Polish cuisine. There was a wide selection of fruits: mangoes, bananas, papayas, oranges, pomegranates, pineapples, but no apples, and no vegetables – potatoes. Initially, there was only goat meat, then the District Officer obtained, with great difficulty, permission to deliver beef, because in India cows are sacred.

The peculiarity of life in Valivade was the street advertisements for films, cold lemonade or ice cream, services such as laundry, floor wiping. Films, mostly American, were played every day.

Apart from cinema, one of the few entertainment options available to young people was riding rented bikes.

There was a lack of fathers in family life, who served in the army or died in Russia. Some mothers worked in various institutions in the estate, e.g. in the hospital, administration, community centers, schools or craft workshops. Others opened their own catering points for those who did not have time to cook for themselves.

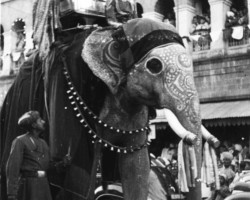

Relations with the Indians were very good. At first, they were often surprised that, unlike the English, the Poles did not treat them with contempt despite the color of their skin. Many of them learned to speak Polish: the postmaster completely correctly, while others – in broken Polish. The starosta’s family was invited to the reception and tour of the palace of the little, 7-year-old Maharaja. After his premature death, in June 1947, the residents of Valivade participated in the coronation of the new Maharaja, Chhatrapati Shivaji VI, with whose dynasty the Circle of Poles from India maintains contacts and in 1999 was represented at the wedding of his son.

The Polish authorities representing the Polish Government ministries in London resided in Bombay. The magazine “Polak w Niechciał” (Pole in India) was also published there, informing about the course of the war and events in the world. The refugees received small but regular financial assistance.

The general supervision of the settlement on the part of the British authorities was exercised by Captain Webb ( the Principal Refugee Officer in the Government of India) . The commander of the settlement until 1945 was a Pole, Captain W. Jagiełłowicz. In October 1945 he was replaced by an Englishman, LT.Col. Neate, for fear that a split between supporters of the Warsaw and London governments might occur. From January to September this function was held by Lieutenant Colonel DS Bhala, and in recent months, during the liquidation of the settlement, by Mrs. M. Button.

After 1945, as part of the cost-cutting measures, the Panchgani centre was closed, and at the end of November 1946 the children’s camp in Balachadi was closed, and their residents were relocated to Valivade.

In 1947, three transports left Valivade for the Homeland. Only 473 people decided to return to communist Poland. Most of the residents decided on the difficult role of political emigrants, convinced that they would be able to serve the Polish cause better outside the borders of the country, reminding at every opportunity that there is no truly free Poland as long as communists rule there.

Exhibition Materials

Photographs

Documents