Quick Links

Paths of Siberians to India

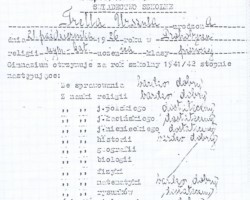

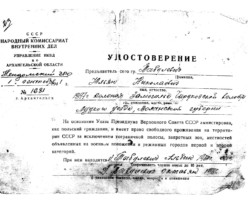

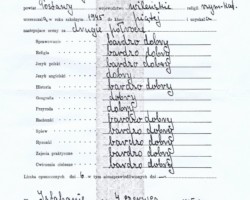

The consequence of the signing of the Sikorski–Mayski Agreement in London on July 30, 1941, signed by the Prime Minister of the Polish government in exile (Władysław Sikorski) and the Soviet ambassador to England (Ivan Mayski), i.e. an agreement restoring diplomatic relations between the authorities of the Republic of Poland and the Soviet Union, particularly important in the context of the new political and military situation in Europe after the German attack on the USSR in June 1941, was the “amnesty” announced by the Soviets on August 12 for all Poles deported in four mass deportations from the Borderlands into the depths of the USSR and those staying in Stalinist prisons and gulags. Although the word “amnesty” was an ideological manipulation, because the Polish exiles were not criminals in any way (the exiles did not end up in the depths of the USSR as a result of any court sentences, and those thrown into prisons and labor camps were arrested to a large extent on fictitious charges), the decision itself was of great importance, because in the long run it gave hundreds of repressed Poles the opportunity to get out of the “inhuman land”. This possibility, however, would be purely theoretical – the prisoners and resettlers from the Kresy were exhausted, starved, deprived of material resources and scattered almost all over the Soviet empire, and their homelands, to which they wanted to return, were in the meantime under German occupation – if it were not for the organized help provided to them by the Polish embassy in Kuybyshev (evacuated there, as a temporary capital of the USSR, due to the advancing German invasion and the resulting threat to Moscow), as well as the command of the Polish army organized in the USSR and the efforts of the Polish authorities in exile. On August 14, 1941, a Polish-Soviet military agreement was signed, thanks to which it became formally possible to create the Polish Armed Forces in the USSR. Their commander was General Władysław Anders. Joining the wing of this army, which was being built not without obstacles (the common name of which is related to the name of the general commander), gave Polish exiles the opportunity to evacuate (the Polish authorities and military command, with the support of the British, eventually forced Stalin to agree to Anders’ army leaving the USSR, even though the Kremlin had plans to quickly throw Poles into the fights on the Western Front – with the Red Army, in the war against the Germans who were aggressively attacking the Soviets), but mainly concerned men capable of fighting and their families, as well as young people who could train with the army and take part in combat later (i.e. the so-called junaks, the youngest of whom were later released after evacuation to Iran and transported to India; the age that qualified for them was set at 14-18 years).

Although General Anders did everything he could to evacuate as many civilians as possible with the army (e.g. by accepting children under a certain cadet age into the Junaks), he was not able to help all of his countrymen. After all, what could be done, given such rules, for a family in which there was no man capable of fighting or no man at all (many children were orphans), or for people who could not reach the army assembly points? Another issue was that the army had strictly limited food rations, insufficient even for the soldiers themselves, who, in addition, shared their meals with their families. Thirdly – unlike in the case of forced resettlers, gulags and prisoners – Stalin gave permission to release Polish orphans from Soviet orphanages from the USSR only at the end of 1941. Thus, the general situation of Polish civilians in the Soviet empire was still dramatic after the “amnesty”, yet thousands of exiles were heading with hope from the cursed places of recent repression to the south of the Soviet Union, where Polish military structures were being organized for a long time and where, together with many of their compatriots, they were waiting for their further fate in exile.

Even earlier, before the “amnesty”, the situation of the exiles was taken over by the Polish authorities, who tried to organize help for them. The Polish government in London and its delegations were not indifferent to the hard labor of their compatriots vegetating in the Soviet Union, but actions in this matter were difficult as a result of the tense relations with the Kremlin, especially since – incidentally – Moscow did not recognize the Polish authorities operating in London as legitimate (the government of Prime Minister Władysław Sikorski, through the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, therefore probed the possibility of helping Poles in the USSR through the territory of India, which was under the rule of the allied Great Britain, which was to be coordinated by the Consulate General of the Republic of Poland in Bombay headed by Dr. Eugeniusz Banasiński). After the resumption of diplomatic relations between Poland and the USSR in July 1941 (which had been unilaterally severed by the Poles as a result of the Red Army’s aggression in the Borderlands) and the announcement of the decree on “amnesty” for exiles, the Polish Embassy in Kuybyshev, headed by Jarosław Kot, organized offices in the Soviet Empire to help the displaced. The fate of Poles, who were in constant need of various kinds of support, was viewed similarly on the international forum. Already at the outbreak of the war, the English established the Polish Relief Fund for the war-torn Polish nation, and in British India the Bombay Consulate later established a similar Refugee Aid Committee, which was tasked with supporting the recent Polish exiles deep into the USSR and had the support of some Indian figures, both British and Indian.

The Polish Red Cross, in relation to the displaced, the gulags and Stalinist prisoners, also did everything it could to send the most necessary things to its compatriots staying in the Soviet Union. And it was thanks to the considerable help of the Polish Red Cross that an extremely important undertaking was initiated, which – as it later turned out – had a significant impact on the adventures of a large part of Poles who wanted to escape from Stalin’s totalitarian oppression. In July 1941, the head of the Consulate General of the Republic of Poland in Bombay – Dr. Banasiński – came up with a proposal to send a transport with humanitarian aid to the Soviet Union for the Poles staying there, to which both the Polish government in London and the local Delegation of the Polish Red Cross in India responded favorably. It soon organized an expedition with food, clothing and medicines, so that after reaching Central Asia by vehicles, it could support the convicts covered by the August “amnesty” in the meantime. The route led through Iran, which had been under British-Soviet occupation since August-September 1941, which made travel easier (there was also a concept of going through Afghanistan, which was dangerous for various reasons), and in the future also organizing the transfer of Poles through this territory (it is worth emphasizing, however, that the British presence in Iran was a major facilitation, because the Soviets, despite the “amnesty” granted and the subsequent consent to the evacuation of Poles from the USSR – both Anders’ army and the civilian population – hindered the implementation of this undertaking at every stage). The expedition was organized by the chairwoman of the Bombay Polish Red Cross – Kira Banasińska, and led by vice-consul Tadeusz Lisiecki. After overcoming many bureaucratic difficulties and collecting donations, on November 11, 1941, six trucks were sent to the southern regions of the Soviet Union (five more were purchased on the way), and thus the transport from Bombay, heading northwest, through Quetta, left India through the territory of Balochistan (present-day Pakistan), and through Iranian Mashhad and then the Kopet Dagh Mountains reached Ashgabat, the capital of Turkmenistan in the USSR.

Meanwhile, due to the dynamically changing situation concerning the creation of Anders’ army and the Polish civilian population gathering around it, other actions were taken, aimed at the increasingly realistic evacuation from the Soviet Union not only of soldiers, but also of other Poles, including Polish children scattered throughout the USSR who, in various circumstances, ended up in Polish orphanages established after the “amnesty” and organized in the south of the Stalinist empire (i.e. at the same time in the region where the Polish Armed Forces were being formed in the USSR), or staying in many Soviet orphanages, as well as wandering alone in the streets and bazaars (lost, lonely after losing their parents or being separated from them).

On October 1, 1941, a letter was sent to the British Foreign Office in London presenting a project to evacuate Polish families to India. Its author was Barbara Vere-Hodge, the president of the Indian branch of the Women’s Voluntary Service for Defence (a British voluntary organization whose members were to provide assistance to the state and society in various ways during the war). However, the British government was not interested in this at the time; London was inclined to provide assistance only to those Poles who could somehow support the Allied war effort, i.e. those joining Anders’ Army. When it became clear that some civilians would manage to escape from the Soviet Union, the government in Delhi also initially proved rather reluctant to accept Poles in India. This country, it should be remembered, was very poor, and additionally heavily burdened by the British war effort at that time. To make matters worse, the Japanese offensive was developing to the east of India – by mid-1942, the Japanese had occupied Burma, directly threatening the territory of the subcontinent. All this meant that the Delhi government was reluctant to take on the additional burden of thousands of Polish civilians. The country’s internal political situation was also complex. By the end of the 1930s, the number of active supporters of Indian independence had grown significantly, and the Delhi government increasingly had to share power with the opposition. The largest anti-British force was the Indian National Congress (IKN), a party that included, among others, Mahatma (real name Mohandas) Gandhi and Jawaharlal Jawaharlal Jawaharlal Jawaharlal Nehru Jawaharlal Nehru Jawaharlal Nehru Jawaharlal Nehru Jawaharlal NehruNehru – one of the most important fathers of Indian independence, won in 1947. 10 years earlier, this group had gained power in all provincial governments, but shortly afterwards, with the outbreak of World War II, it itself resigned from this power. IKN politicians abandoned their newly acquired positions as a sign of opposition to London dragging India into the global conflict without providing any guarantees that in return the country would gain independence. As a result, the Indian National Congress once again became the opposition (considered illegal) and in 1942 initiated the “Quit India!” movement against the British presence on the subcontinent. Thus, when the question of the evacuation of the Poles arose on the international forum, the Delhi government was occupied on at least three levels: the high cost of supporting the British war effort, the defence of the territory against the Japanese advance, and the fight against internal political opposition at home.

In addition, when the politicians of the Indian National Congress resigned from their posts, the government in Delhi expanded cooperation with another group operating in India – the Muslim League, founded by indigenous people, similarly to the IKN – a political and religious party which, although loyal to the British, had been demanding the creation of a separate state for Indian Muslims – Pakistan – since 1940 (the issue of an independent Pakistan had arisen earlier, but it had not been formulated by the League; the issue of an independent India arose in 1930, when the Congress demanded it). The problems of the British government in Delhi – even if in this case fuelled by it, as the British skillfully won over the animosities between the IKN and the League, which had cooperated with each other in the past – were compounded by the growing Hindu-Muslim conflict (one of the later effects of which was the creation in 1947 – alongside independent India – of a separate state, i.e. Pakistan).

In this context, the Delhi government refused to accept a larger group of Poles for a long time, apart from agreeing to accept 500 Polish children in January 1942. This was already an important decision, although from the Polish perspective it was a drop in the ocean of needs. However, another dilemma arose – where and how to place the orphans? The Indian government suggested placing the children in boarding schools and convents of various Christian institutions. It was also suggested that they be placed with wealthier Indian families who would agree to take the youngest under their care. However, the Polish side feared that dispersing the children would result in their loss to the Republic – in the sense of losing their sense of identity, Polishness. Moreover, such solutions were impractical because the children did not know English, let alone the various Indian languages in different provinces, and it would be difficult for them to find a place in a foreign-language environment. For these reasons, it was preferred to concentrate Polish refugees in larger groups, create Polish settlements, with Polish authorities and education. But although the Polish government in London could allocate appropriate sums for these purposes, first places would have to be found to set up these settlements, and the Delhi government was in no hurry to do this.

In this seemingly stalemate situation, the Viceroy of India appealed to the Indian “princes” for help. In response, the ruler of the principality of Nawanagar, Maharaja Digvijaysinhji, expressed his willingness to accept 500, and later 1,000 Polish orphans and half-orphans. He bore the monarchical title of jam saheb and as a young man, while staying in Europe with his adoptive father, he met the Paderewski family, from whence his fascination with Polish culture began.

The principality of Nawanagar, located on the Kathiawar peninsula in western India (today’s Gujarat state), was small, but its rulers were wealthy and the maharaja had considerable political influence at the time. Namely, various Indian monarchs, i.e. “princes”, had had their own organization since 1920 to represent their political interests to the government. It was called the Chamber of Princes (COP), and was always headed by one of the local monarchs. In 1938, this function was taken over by Maharaja Digvijaysinhji. For a ruler, he was relatively young at the time (he was 42 years old and had been on the throne for five years), so many people doubted whether he would be up to the new task. However, he turned out to be a capable politician and quickly reactivated the COP, which was losing its importance at the time. At the same time, Digvijaysinhji showed himself to be a monarch loyal to the British. This was expressed, among other things, by his support for the British war effort, also through active membership in the Imperial War Cabinet and the Pacific War Council. Therefore, the theses that have appeared here and there that this maharaja was a participant in the Indian independence movement should be completely denied. However, in the decisive year for many Polish exiles, 1942, Digvijaysinhji was both a very important Indian politician, a collaborator of the British, and a friend of the Poles, which was probably decided by his past meeting with Ignacy Paderewski (known worldwide not only for his outstanding talent as a composer and virtuoso piano player, but also for his activity on the political scene, which contributed to Poland regaining independence after 123 years of partition) and his family.

The village of Balachadi (pronounced Balaćadi), west of the capital of Nawanagar – Jamnagar (pronounced Dżamnagar), was designated as the destination for the Polish children in the principality of Nawanagar. Justifying his decision to accept the youngest, the monarch is said to have said: Deeply moved, moved by the suffering of the Polish nation, and especially by the fate of those whose childhood and youth are passing in the tragic conditions of the most terrible of wars, I wanted to contribute in some way to improving their fate. So I offered them hospitality in lands located far from the turmoil of war. Perhaps there […] these children will be able to regain their health, perhaps there they will be able to forget everything they have been through and gain strength for future work as citizens of a free country.

The decision of the maharaja was beneficial to all parties. The Indian “princes” enjoyed a certain autonomy in their territories, both legal and fiscal. For example, they collected taxes and thus had their own treasury. The monarch could therefore accept children and build a settlement for them, if he wanted, without looking back at the government in Delhi (provided, of course, that this government would agree to accept the children in India at all, but this was decided at the beginning of 1942). Moreover, the monarch could also support the settlement with his own funds (which he often did) and in this case he was also not dependent on the Delhi or London bureaucracy, although it should be noted that the Polish settlements were mainly maintained from the Polish government’s finances. This autonomy of the maharajas helped the Poles not only in the case of Digvijayasinhji. Namely, his second greatest gesture towards the former exiles deep into the USSR was the establishment of the Polish Children Fund. Using his prominent position as the president of the COP, he persuaded and led by example many other local monarchs and Indian magnates to provide funds to support the stay of Polish children in India. Each donor was to commit to providing a specific sum to support the youngest Poles. In total, over 80 donors came forward. Maharaja Digvijayasinhji’s initiative thus allowed the Delhi government to save its honor – after all, it had already agreed to accept the first children, but due to the initiative of the ruler of Nawangar, it did not have to worry about their placement – and helped the Polish government by solving the problem of organizing the first Polish settlement for refugees in India.

However, the children had to be transported to their new Indian home, and first – scattered, exhausted, sick, often lonely after a loss (e.g. earlier imprisonment of parents or their death, which usually resulted in their ending up in Soviet orphanages), or after their parents got lost after the “amnesty” and after the family left the place of exile – they had to be gathered in the Soviet Union. The greatest merits in this field were demonstrated by the employees of the Polish Embassy in Kuibyshev – the delegates of the mission – and the volunteers cooperating in this work. They put great effort into finding Polish orphans and half-orphans – apart from those gathered in Polish orphanages established after the “amnesty” – vegetating in terrible conditions in Soviet orphanages ( dietdoms ), or directly on the streets of larger and smaller cities (as the so-called bezprizorni – homeless) and gathering them in centers in Central Asia, especially in Ashgabat on the border with Iran, a city that was soon to become the main gathering point for the youngest Poles.

Some children and their volunteer guardians – and there were people among them who acted with extraordinary dedication, such as the famous pre-war actress and singer Hanka Ordonówna (born Maria Anna Tyszkiewicz, née Pietruszyńska) – if they heard about the “amnesty”, they reached the scattered assembly points on their own, usually in terrible conditions, sometimes marching for days on foot, without food or means of subsistence. It is worth emphasizing that not all the exiles heard about the “amnesty”, because the Soviet commandants of the camps or special estates, the heads of the kolkhozes and sovkhozes did not want to get rid of the almost free labour force and dismiss the camp inmates or the displaced persons. However, most Poles were aware of the new situation and tried to move to the south of the USSR. This was also the case with orphans deprived of any guardians, who, extremely determined by the news about the organization of assembly points there (Polish orphanages, which they learned about, but also centers for the formation of Anders’ army, because sometimes they were the only ones they knew about), covered the long distance – or tried to cover it – by themselves. Sometimes the role of guardians was taken over in such cases by older siblings (where older could mean, for example, 7 years old), suddenly forced to grow up and take on enormous responsibility for the uncertain fate of their sisters and brothers, which involved leading them through an unknown, vast area, feeding them (ergo – obtaining food on the way), and sometimes even carrying much younger siblings on their own.

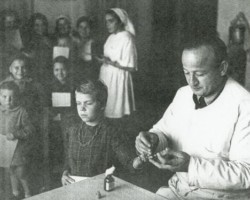

Meanwhile, it was in Ashgabat, where the first children were brought from Polish orphanages around Tashkent and Samarkand (both cities are currently in Uzbekistan), that the trucks from the aforementioned transport with previously delivered charity aid for the exiles, led by Dr. Tadeusz Lisiecki, were still there. In a situation where the Polish authorities finally received permission from the Soviets for the youngest children to leave the USSR (December 24, 1941) and a signal from the government in Delhi that they were ready to receive them on the subcontinent (January 3, 1942), Vice-Consul Lisiecki’s charity expedition could serve as a great opportunity to transport the children to India, from where they had come. Preparations for the return expedition began efficiently and quickly, even though the condition of the children, who were from then on gathered mainly in the temporary orphanage in Ashgabat (as the main gathering point, organized, among others, thanks to the great effort of Michał Tyszkiewicz, Hanka Ordonówna’s husband), was initially terrifying – they were not only lonely, starving and overcome with overwhelming sadness, but also usually sick, consumed by fever, often suffering from whooping cough or scurvy, or even typhus.

The short period of their convalescence allowed for subsequent groups to be brought to Ashgabat – from other distant assembly points, Polish orphanages organised in the south of the USSR after the “amnesty”, or previously established Soviet orphanages operating in parallel.

On the journey from Ashgabat to India, which began on 12 March 1942, a total of 166 children were taken (some sources give the numbers of 160 and 175). This was the first transport of Polish exiles outside the Soviet Union and at the same time the first of three evacuation expeditions organised by land for Polish children transported to the subcontinent. The trucks with the youngest children were accompanied by one ambulance intended for sick children. The dangerous journey to Indian territory, through mountains and deserts, lasted about a week and was full of dangers – no wonder that Hanka Ordonówna, who took part in it, called Dr. Lisiecki, who led the expedition, “the lord of life and the lord of death”. On the way – in Iran – the transport stopped for a while for quarantine in Mashhad, where the children received help from the British and Americans. However, after the expedition reached Baluchistan – already in India – the children and their guardians transferred to a train in the town of Nok Kundi (on the current border of Pakistan with Iran), from where they were transported by train via Quetta to Bombay in April. It turned out that their final settlement in Balachadi – designated by Maharaja Digvijaysinhji after Delhi’s January agreement to accept exiles in India – was not ready yet. The Poles, children and their guardians were therefore placed in three villas in the holiday resort of Bandra within the administrative boundaries of Bombay (now part of the metropolis called Mumbai). This was how a temporary centre was set up on the way to their destination. The first former exiles deep into the USSR were moved to the settlement in Balachadi, which was then being built, in mid-July 1942 (they probably arrived there on the 16th or 17th of that month).

Encouraged by the success of the first evacuation expedition, on June 1, 1942, the Polish government asked the authorities in Delhi to accept another 500 children into India, and when it was accepted, the Bombay Delegation of the Polish Red Cross sent a second transport to the Soviet Union, this time consisting of 24 trucks. In July, 220 children were transported along with 17 guardians. The transport encountered a serious obstacle, namely the heavy flooding of the Punjab Indus River. It was a real disaster for the local population, as huge areas of land were flooded, but it also meant a break in the journey for the Polish column, as the flood submerged roads, bridges, and railway tracks, making any passage impossible.

Polish children and their guardians waited out the cataclysm in Quetta in Baluchistan, where a temporary center was organized for them. After the rainy season ended – which in that region, in northern India, usually lasts from July to September – in September it was possible to bring the children to their destination, by road south, to the city of Hyderabad in the Sind province, from where the youngest were sent by train to the already completed settlement in Balachadi. The third evacuation transport of children from the USSR was organized in December 1942 and took 250 children. These land escapades were fraught with danger. Although some of the transported recalled the openness of the Persians, who would leave their homes to treat the weary travelers with apricots or peaches, everyone also remembered the dangerous mountain roads, as well as the fearsome lawlessness that reigned on the communication routes of Iran and Baluchistan in India, which sometimes resulted in shooting to drive away potential robbers looking for easy loot at night. Vice-consul Tadeusz Lisiecki also recalled how the first expedition was hit by a sandstorm and almost a diplomatic storm when it turned out that the Poles had not notified the transport on time about the arrival at the USSR border and the expedition had to enter the Persian border almost by force to get out of the Soviet Union. In India, on the other hand, the children were received with kindness by both the Indians and the British, who often welcomed them in special committees waiting at the stations.

Dr. Lisiecki’s first expedition brought another benefit. It was a reconnaissance not only for the next evacuations of children to India, but also for the general evacuation of Poles (conscripted into Anders’ Army) by land from the USSR to Iran, i.e. by an alternative route to the one planned via the Caspian Sea (from Soviet Krasnovodsk, currently Turkmenbashi in Turkmenistan – to Pahlevi, currently Bandar-e Anzal in Iran). Ultimately, however, it was by sea that most of the Polish Armed Forces in the USSR and civilians escaped from the area of the Stalinist regime, as Lisiecki advised the Polish government against road transport. To sum up the whole evacuation process at this point, it should be noted: in total – through the Caspian Sea and overland (between Soviet Ashgabat and Iranian Mashhad, which was the route of the above-mentioned children’s transports and other, later rescue expeditions carried out until the end of 1943, despite the severing of diplomatic relations by the Soviet and Polish governments in the meantime, which was the result of the discovery of the Katyn mass graves) – about 78,000 troops were evacuated (apart from several hundred soldiers, mainly sick, who were transported overland via Mashhad, the army was transported by ship) and over 38,000 civilians (about 36,000 in two rounds by sea and over 2,000 by land via Mashhad, from where they continued to Tehran or immediately to India, among others).

In three car expeditions organized by the Polish Red Cross, 650 children were saved (according to data from the Delegation of the Ministry of Labor and Social Welfare in Bombay, there were about 680 children: orphans, half-orphans, separated from their parents in the USSR in various circumstances – because that was the kind of people for whom the three expeditions were intended, however, from the preserved memories it appears that a small number of the youngest orphans also reached India later, also via Mashhad, and then by a roundabout route via Tehran, then often Isfahan, and then via Khorramshahr, by sea, to Karachi in India – hence the discrepancies in numbers). The total age distribution of the youngest from the first two PCK transports (for which more detailed data have been preserved) was as follows: 4% were under four years old, 20% between five and eight years old, 32% between nine and twelve years old, 28% between thirteen and fourteen years old, and 16% were over fifteen years old. In total, during the entire evacuation of Poles from the USSR, at least 14,000 Polish children were transported to Iran (including in two rounds by sea, with Anders’ army – apart from a relatively small number of about 700 soldiers who were transported by land – and the bulk of civilians, respectively: over 3,000 in March-April 1942 and over 9,500 in August 1942). However, before all this happened…

Although, as mentioned, in January 1942 the Delhi government accepted the admission of five hundred children, and another five hundred in June of the same year, these limitations posed a problem for the Poles, as it was far below the needs, especially since this limit was mostly used up by the aforementioned three Polish Red Cross car transports from Central Asia to India. A separate issue was therefore the fate of the numerous children who managed to escape – as civilians – with Anders’ army, and who, after evacuation from the USSR, already in Iran (former Persia), were separated from the soldiers along with the remaining civilians. For some time, there had been plans to accept the youngest in British colonies in Africa, but the centers there were not ready. Ultimately, in the summer of 1942, the London India Office decided to accept another five thousand Polish exiles, including largely children, but in terms of numbers – primarily adults. In the case of the youngest, however, the main ones to settle in India were again orphans (and half-orphans, as the alleged orphanhood could have been the result of ignorance about the fate of their parents in the USSR, who sometimes, in fortunate cases, later turned up). Nevertheless, the government in India set strict conditions, announcing, for example, that it would strictly control the finances of refugee centers, and that settlements for Poles could be built in places with difficult climates for Europeans, and that the standard of the houses would be low, they might not have electricity, etc.

This declaration was the subject of diplomatic friction, but it should be added that ultimately the conditions in the refugee settlements were not as bad as they were – perhaps to discourage – outlined at the time. Another clear condition for accepting Poles in India was that the Polish government in London would co-finance the stay of its citizens on the subcontinent (it was to pay extra if the funds obtained from donors in India proved insufficient), which was accepted. In any case, the offer to accept five thousand Polish refugees (children and adults) was a long-awaited breakthrough.

Again, in the context of locating Poles in India, the problem of transporting people to refugee centers on the subcontinent arose. This time, it mainly involved mothers with children (rarely men) rescued from the Soviet Union. They had to travel overland through Iran and then – unlike in the case of the three Polish Red Cross car expeditions mentioned above – by sea to India. At that time, they had already been evacuated by land to Mashhad, or with Anders’ army, on often overloaded ships, across the Caspian Sea from Krasnovodsk to the Iranian port of Pahlevi (the sea transport of soldiers and civilians took place together in the two aforementioned tours: in March-April 1942 and in August 1942) in the Soviet occupation zone, where they underwent quarantine in improvised conditions (accompanied by burning all their clothes and cutting their hair). From Pahlevi – where most Poles from the USSR went in “transit” – civilian Poles were transferred (via dangerous mountain roads) southeast to Tehran, and then their journey took various forms. Some of them were sent by train to a transit camp organized in July 1942 on the grounds of the Iranian army barracks in Ahwaz (from there the refugees later set off for the seaport in Khorramshahr, because Ahwaz itself was located “only” on a river, and then they sailed to India or Africa, but not only that, because refugees from Iran spread out to many corners of the world – they also ended up in New Zealand and Mexico). Some – this mainly concerned children – remained in Tehran (several hundred Polish children in the Iranian capital were taken in thanks to the kindness of Anglican missions, Swiss Salesians and financial support from the Vatican). However, when it comes to the youngest children in Iran, the largest number – over three thousand in total – eventually ended up in Isfahan, which was later called the city of Polish children (some of them were taken care of by representatives of the Anglican and Roman Catholic churches).

For the transports that were ongoing simultaneously with the evacuation of Poles across the Caspian Sea, taking place exclusively by land from Soviet Turkmenistan to Iran (however, a relatively small group of refugees from the USSR – civilians and a small group of sick Polish soldiers – took this route), the temporary place of residence for the Poles – including about 1,700 children, including 650 (vel 680) of the youngest rescued in the first, above-mentioned three expeditions of the Bombay Polish Red Cross – was the aforementioned city of Mashhad. Some of them went on to Tehran, but many people who were then to sail from Iran by sea to India (but also to other countries) were transported – not from the beginning, however, but at various times – through Ahvaz to the above. The port of Khorramshahr on the Persian Gulf, which was an excellent stage for further travel due to its coastal location (some of those evacuated from the USSR by land, via Mashhad, did not ultimately go to India, but to Africa, for example). The city was located over 140 km from Ahvaz, the main temporary residence of Poles in Iran. Sea transports set off from Khorramshahr, including to Indian Karachi (Karachi, pronounced Karaći, in the Sind province, currently in Pakistan), where transit camps for Poles were organized by the British authorities. According to data from the period 24 August 1942 – 31 December 1944 (not including the first four transports of Polish refugees from Iran to Karachi, organized in August 1942, of which the third and fourth – there is detailed data on this – amounted to 779 and 726 people, respectively), a total of 20,984 Poles arrived in Karachi. Of these, not all, although the vast majority, ended up there from Iran. Poles, on the other hand, went further from Karachi – either to Africa, or to Mexico, or to other places in India itself. According to the statistics cited from the above period, 12,642 people left for the Dark Continent, 1,403 for Mexico, and finally 4,356 for the interior of the Indian subcontinent.

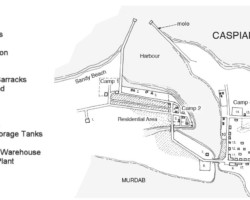

In Karachi, a temporary camp was opened on the premises of the Haji Pilgrims Camp, a camp for pilgrims going on the hajj – a pilgrimage to Mecca, which is one of the five pillars of the Muslim faith and at the same time one of the most important events, and at the same time an obligation, in the religious life of Muslims. Since war operations temporarily blocked the possibility of Muslim pilgrimages, the camp was empty and could be used by Poles. Then, from September 1942, refugees were directed to the temporary camp in Country Club, located a dozen or so kilometers from Karachi, and in practice a place where tents for Poles were placed in the desert.

Hence, as it was noted ironically, only the British sense of humor could have caused such a place to be called a Country Club (a Country Club, or a Province – such private clubs outside the city for recreation were organized by the British in various places in long-colonized and then still occupied India). For this reason, another, more convenient place was sought, which would accommodate more people. And so the next transit camp for refugees in the vicinity of Karachi was Malir, located 24 km from the city (initially it was prepared for the allied American army, belonging to the Allied forces). It is worth emphasizing that the wife of the Polish consul in Bombay, Kira Banasińska, had an influence on the temporary transfer of the camp in Malir to the Poles. It should also be added that the camp in Malir, used for the Poles since March 1943, had the advantage over the Country Club camp that its buildings were made of brick, which meant that the living conditions of refugees in both places were completely different. It could accommodate 2,200 people at one time, although these limits were exceeded.

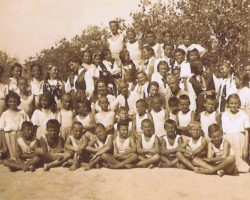

Although Maharaja Digvijaysinji agreed to accept 500 children, which he later expanded by another 500, this was still insufficient, although substantial, help. Eventually, around a thousand of the youngest refugees from the USSR passed through the settlement created under his patronage in Balachadi in the principality of Nawanagar, intended only for children and youth (there was considerable turnover there as well as elsewhere, if only because children went to their found parents when this happened; at any given time, there were between 600 and 800 children living in this settlement, because that was the maximum that could be there at one time). Although the everyday life of refugees quickly developed in Balachadi – there was, among other things, a primary school, a chapel, a hospital, a canteen – it quickly turned out that the settlement was located in malarial territory. Therefore, additional Polish centres had to be established in India, if possible located in more climatically favourable areas.

The largest and most important of them were probably created from the end of March 1943 in Valivade in the principality of Kolhapur, 480 km south of Bombay (currently Valivade is simply part of Kolhapur). The then Maharaja of Kolhapur was a minor, and the actual power there was held by the British regent, so in this case we should probably be grateful to the British authorities for the decision to place Poles in Valivade. In any case, it was Valivade that was to become the most famous Polish settlement in India, a truly Polish town. It housed five thousand people (largely mothers with children), and its greatest advantage was probably that it was located at an altitude of 700 m above sea level, so the climate there was cooler and much nicer than in the settlement in Balachadi.

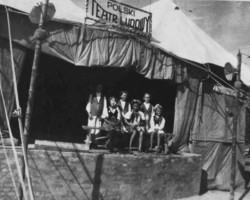

The first Polish group reached Valivade on June 11, 1943, but at that time the settlement was not yet fully ready. In time, it was finished, and the refugees who stayed there organized their lives there. Valivade eventually housed schools, a church, workshops, shops, a printing house, a hospital…

The British rulers in India tolerated the local climate no better than Polish refugees, hence the old colonial tradition of establishing so-called hill stations , mountain towns where white rulers could live during the hottest months of the year. One such place was Panchgani (pronounced Pańćgani), over 200 km from Bombay, in the mountains, in the Satara district. It was a sanatorium (and also famous for its boarding schools) and a small Polish centre was also established there. The Polish institution in Bombay leased villas there, which could accommodate up to 30 people. They sent mainly people recovering from tuberculosis, including Hanka Ordonówna. In addition, some Polish youth eventually found themselves in convents, not only in Panchgani itself, but also in Bombay, Mount Abu (today the state of Rajasthan) and Karachi. Everywhere, a new stage of life was beginning for the former exiles from the former Eastern Borderlands of the Second Polish Republic…