Quick Links

Camps, Conventions and Refugee Centers

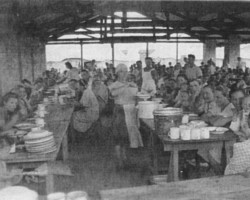

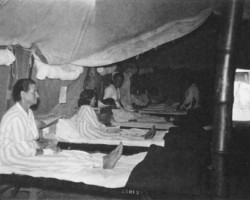

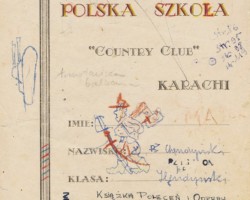

One of the first places in India that Poles ended up in after being evacuated from the Soviet Union to Iran and then on their way to the subcontinent was the Country Club transit camp near the port city of Karachi. After the refugees were transported to this city by ship, they were transported to a tent camp, which was in fact the Country Club located in the Great Indian Desert. In the years 1942-1945, around 20-21 thousand people found shelter there. Since it was a transit camp, the composition of the refugees in it was constantly changing. Some Poles left from there for other Polish residence centers in India, mainly to a permanent, large settlement in Valivade. Others, having been in the Country Club for two or three months, were transported to camps in Africa, Mexico, New Zealand…

The Country Club, administered by the British authorities in cooperation with the Polish authorities, had a relatively developed social life. There was a hospital, a school, and artistic classes. An important undertaking for the refugees, already in the first years of the camp’s existence, was the construction of a temple to sustain their faith. A small, Catholic, wooden church was built as a pleasant structure in the stony desert. It was consecrated on February 14, 1944 by Alcuin van Miltenburg. Initially, pastoral duties in the church-chapel were performed by Franciscan priests from the monastery in Karachi. The monks celebrated mass every Sunday and holidays. However, the lack of a permanent priest had already been felt earlier, so thanks to the efforts of the refugees themselves, as a result of the actions of the Consulate General of the Republic of Poland in Bombay, Father Antoni Jankowski was sent to the camp. He began his pastoral ministry in the Country Club in August 1943 and performed it until the camp’s liquidation. Importantly, he also worked as a catechist, educating mainly young Polish refugees religiously. Józef Beskowicz was the church organist. It is worth noting that religious life was not limited to prayers, services, or religious practices in the camp itself. One year, during the celebration of the feast of Christ the King, on November 26, the residents of the Country Club were allowed to travel to Karachi and participate in the celebrated mass and procession in St. Patrick’s Cathedral. Such trips were rare, however. It should also be emphasized that not all Polish refugees, mostly from the multi-denominational Eastern Borderlands of the Second Polish Republic, identified spiritually with the Catholic religion.

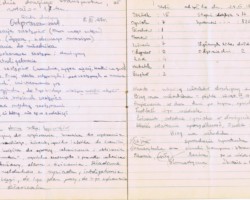

Schooling was organized in the camp. However, it was not without problems, because not only children but also teachers were subject to constant rotation, but due to the prolonged existence of the Country Club (initially the transit camp for Poles was to function for a short time and was established temporarily for a short period), it was realized that conducting educational activities was becoming necessary.

One of the first places in India that Poles ended up in after being evacuated from the Soviet Union to Iran and then on their way to the subcontinent was the Country Club transit camp near the port city of Karachi. After the refugees were transported to this city by ship, they were transported to a tent camp, which was in fact the Country Club located in the Great Indian Desert. In the years 1942-1945, around 20-21 thousand people found shelter there. Since it was a transit camp, the composition of the refugees in it was constantly changing. Some Poles left from there for other Polish residence centers in India, mainly to a permanent, large settlement in Valivade. Others, having been in the Country Club for two or three months, were transported to camps in Africa, Mexico, New Zealand…

The Country Club, administered by the British authorities in cooperation with the Polish authorities, had a relatively developed social life. There was a hospital, a school, and artistic classes. An important undertaking for the refugees, already in the first years of the camp’s existence, was the construction of a temple to sustain their faith. A small, Catholic, wooden church was built as a pleasant structure in the stony desert. It was consecrated on February 14, 1944 by Alcuin van Miltenburg. Initially, pastoral duties in the church-chapel were performed by Franciscan priests from the monastery in Karachi. The monks celebrated mass every Sunday and holidays. However, the lack of a permanent priest had already been felt earlier, so thanks to the efforts of the refugees themselves, as a result of the actions of the Consulate General of the Republic of Poland in Bombay, Father Antoni Jankowski was sent to the camp. He began his pastoral ministry in the Country Club in August 1943 and performed it until the camp’s liquidation. Importantly, he also worked as a catechist, educating mainly young Polish refugees religiously. Józef Beskowicz was the church organist. It is worth noting that religious life was not limited to prayers, services, or religious practices in the camp itself. One year, during the celebration of the feast of Christ the King, on November 26, the residents of the Country Club were allowed to travel to Karachi and participate in the celebrated mass and procession in St. Patrick’s Cathedral. Such trips were rare, however. It should also be emphasized that not all Polish refugees, mostly from the multi-denominational Eastern Borderlands of the Second Polish Republic, identified spiritually with the Catholic religion.

Schooling was organized in the camp. However, it was not without problems, because not only children but also teachers were subject to constant rotation, but due to the prolonged existence of the Country Club (initially the transit camp for Poles was to function for a short time and was established temporarily for a short period), it was realized that conducting educational activities was becoming necessary.

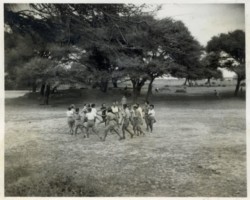

The camp’s table tennis team defeated the American garrison, the chess players also defeated the Americans, and in the sports festival of English, Indian and Polish youth, the girls from the Country Club won prizes for running and long jump, while Stefan Ślusarczyk won four events for the boys. In team games, the Polish refugee teams clearly beat the English and Indian teams three times: in basketball, volleyball and football.

For younger children, aged 3-7, a kindergarten was set up in the transit camp. The kindergarteners gathered every morning in a separate tent, mainly for play, under the supervision of the kindergarten manager. However, the children lacked toys. On November 25, 1942, a special, carpeted tent opened a “garden” for kindergarteners, equipped with new toys, picture books, etc. This “garden” was created at the initiative of a representative of the Polish Red Cross Delegation in Bombay, with the outstanding participation of the wife of the governor of the Sind province, where the Country Club was located – Lady Dow, who was heavily involved in various forms of assistance for refugees.

The camp also had an orphanage for the youngest. Educational activities were also conducted there. The orphanage staff included: Franciszka Gryzel – the manager, Łucja Bałabanow, Maria Świątek, Maria Socha, Felicja Korzuch, Julia Korzuch, Kazimiera Pieczonka, Zofia Badura, Wanda Żurek and Genowefa Łużna – janitors, Alfons Wróblewski and Ludwika Kawałek – both from the Physical Education Department. Also involved in caring for the children were: the aforementioned priest Antoni Jankowski, librarian Janina Stępień, and day-care workers – Janina Mazurkiewicz and Genowefa Haracz.

The Country Club community centre operated according to a monthly plan, which the community centre worker presented each month to the Polish Delegation of the Ministry of Religious Denominations and Public Enlightenment in Bombay, along with a report. Although there were occasional deviations from the planned plan, the main outline of the work in the community centre remained almost unchanged, namely: every evening the community centre worker (usually Ludwika Kawałek, who had graduated from a humanities high school before the war and who, after being deported and evacuated from the USSR, had attended a pedagogical course in Tehran) read out the latest press releases and gave a lecture. In her work, she was directly subordinate to the school principal, who took care of this aspect of camp life. In the community centre, the refugees found various forms of entertainment, social games, listened to radio announcements, music from records, etc.

The camp commander, Major Allan, took care of the equipment of the recreation room and thanks to him it was enriched with English brochures and newspapers as well as equipment for various games. Some refugees prepared interesting reports or talks for the evenings. However, this did not replace cultural life in its entirety, it was not its only manifestation.

The Country Club also had a library, which was looked after by the aforementioned Janina Stępień. The library was equipped with publications by authors such as Słonimski, Baliński, Pruszyński, and brochures by Wacław Solski. Similarly to the youth club, people eager to read aloud gathered there.

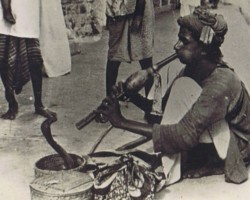

Polish refugees, as part of diversifying their cultural activities, sought to establish closer contacts with the local population by organizing performances enriched with folk dances and Polish songs. They were invited and took part in various celebrations outside the camp. During one of the festivals in Karachi, a Polish stand was set up, informing Indians about Polish history and culture. The Polish stand also provided an overview of the work of the residents of the transit camp; there was, among other things, a lot of beautifully crafted handicrafts. A constant problem in the above-described artistic shows of native culture was the acquisition of the most necessary musical instruments and costumes and theatrical accessories for the performing groups. However, the theatre functioned.

On December 8, 1943, a new transport of refugees arrived at the camp – from Ahvaz. At that time, after the new arrivals had settled in tents, a drama group was organized among them, which was already operating in Ahvaz (after arriving in India, some of its members quickly ended up in the Valivade settlement, while another group remained in the Country Club transit camp, to which people willing to co-create the group were co-opted; however, the members changed as more and more people left – deep into the subcontinent, to Africa…). The first theatre performance took place on December 16, 1943. The program consisted of dances, songs, recitations, and genre scenes. Work is in full swing, new talents are sought, new exercises are being practiced, new ideas are being created, new arrangements are being made. Initially, there were no ready-made texts, scripts, sheet music, any literature, or professional management for the amateur group, but soon the head of the music and vocal department wrote sheet music based on her own melodies and divided them into voices. From individual and collective ideas, scenes and monologues were created. The topics were comic current events from everyday camp life and old, pre-war memories, as well as soldier songs, recitations and stage fragments from the life of the Polish army and its participation in the war.

They quickly found: a singer, acting as artistic director and director, an accompanist who played Chopin’s pieces on the piano by heart, and many others, creating, among other things, ballet and developing dance numbers for programs. In time, performances, shows, concerts and plays took place in the camp every week or every two – each time a new program was performed. The camp commandant – British Captain Allen, supported the Poles from the artistic team, contributing to the development of the scenography and technical means that the team had at its disposal at the beginning of its stay at the Country Club. Polish refugees were also invited to perform outside the camp, for example, at the invitation of the American Red Cross, they went with their program to Karachi. For the English and Americans, because there was a language barrier, events were staged, such as Polish folk dances and singing, which did not require interpretation. In addition, soldiers from the nearby American military camp, especially those of Polish origin, often visited the Country Club precisely because of the theater that operated there in the years 1943–1945.

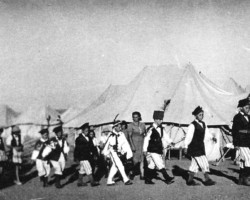

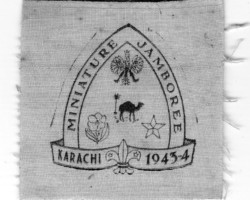

Scouting also played a very important role in the social life of the camp. For many, it was the most important organization at that time. Almost all the youth of the Country Club belonged to the Scouts or Cub Scouts, despite the constant rotation and many people leaving because of departures to Africa or to the permanent Indian settlement in Valivade. Boy and Girl Scouts, as well as Cub Scouts, took an active part in national and church celebrations. Parades, processions, Holy Graves at Easter, where honorary guards were kept, were organized to a large extent by the Scouts. Once a week, the Country Club hosted English Scouts – Rover Scouts – from a nearby military camp. The Scout troop in Karachi remained in constant contact with English and Indian Scouts. Joint Scout conferences were held every Thursday, in which representatives of the troop participated as much as possible. The culmination of this cooperation were two Scout Jamborees lasting several days with the participation of invited scouts from outside the Country Club (from 31 December 1943 and from 2 January 1944). As part of these, joint field exercises were carried out. It is worth mentioning that the scouts were very involved in supporting the Polish scouts. They helped them, sometimes using sign language, to acquire skills. So the Poles took advantage of their knowledge and experience, and the Poles, in turn, showed them, for example, how to tie knots, use semaphore signals, taught young refugees how to make decorative leather products, album covers, etc.

At the Country Club, the youngest in the camp were grouped in Cub Scout troop groups – girls and boys separately – with different names, including the “Pszczółki” troop.

Their number changed, as in many similar initiatives, with the departure of some children to permanent settlements in India or to camps in Africa. Despite the difficulties that existed in the transit camp, the pack meetings were held regularly (similarly in the scouting of older youth). The Cubs were happy to attend them, and the guardians tried to diversify their time with practical activities, acquiring skills… In addition, the Cubs took part in all the camp ceremonies, such as academies and parades. Scouting enjoyed the full support of parents…

In order to reflect the everyday life of the Country Club residents, it is necessary to mention the possibility of spending a holiday on Manor, a small island in the Arabian Sea, for a small fee. Polish refugees travelled there by motorboat from the port in Karachi. On this island, holiday cottages were built for English military families, and British soldiers who had been wounded during the war campaign in Burma and Malaya also spent their time there to recuperate. However, four cottages were made available to the employees of the Country Club camp. The island, rich in vegetation, after the tents and desert of the transit camp, seemed like a real paradise to the Poles – trees, the sea and the beach all around. Provided with dry provisions delivered from the camp, supplementing their diet with vegetables and fruits that could be bought locally and fish freshly caught by local fishermen, the former exiles could rest and, at least for a while, try to forget about their wandering fate.

In addition to the Country Club transit camp, there was a second Polish camp for former exiles in the vicinity of Karachi from the spring of 1943 – in Malir. It operated for a relatively short time, because in the same year all the refugees sent there left it, only some of whom left for the permanent Polish settlement in India in Valivade near Kolhapur, while others followed their wandering path, including to Africa (the docking by ship from Iran to the port of Karachi was for them only a stage on the journey to the Dark Continent, where Poles also reached directly from the former Persia). However, over the several months of the camp’s operation in Malir, social life was developed there. It was created by a large group of over 2 thousand refugees who found themselves in this place.

The necessity of the situation demanded a regulated everyday life, supervised by the administration headed by the starost Władysław Jagiełłowicz. Thus, Poles living in the camp blocks had to reckon with the regulations and restrictions that usually affected refugees in almost every aspect of their functioning.

This was evident even in mundane activities, such as washing, which they did themselves, with a small amount of soap and 100 g of soda per week (only washing for the educational institution, i.e. the orphanage located on the camp grounds – where not only orphans or half-orphans lived – was employed by an Indian contractor). A separate bar of toilet soap was allocated for washing. Difficult living conditions, although better than in the case of another Polish transit camp near Karachi – consisting of rather primitive Country Club tents and not brick buildings like in Malir, as well as the harsh climate and the difficult location near the desert (from where large amounts of sand blew in), did not have a negative impact on the general activity of the Poles. Waiting for departure from the camp was made more interesting by, for example, celebrating Polish national and Christian holidays. Easter 1943 passed as always in a solemn mood, children from schools and educational institution located in the camp received funds funded by the Polish Delegation of the Ministry of Labour and Social Welfare in India, which took care of refugees. The holiday of May 3 was commemorated with a scout parade, celebrated with a ceremonial academy, a holy mass (Sunday services were held in one of the blocks, priestly service was performed by chaplain Father Leopold Dallinger and Father Zygmunt Jagielnicki), which was also celebrated on many other occasions, including May 12 – the eighth anniversary of the death of Marshal Józef Piłsudski. The camp also celebrated the name days of important Poles, especially memorable were the “quadruple” name days in honour of the birthday boys – General Sikorski, General Anders, President Raczkiewicz and the mayor of the Malir camp, the aforementioned Jagiełłowicz. The news of the death of the former – on 4th July 1943 – covered the inhabitants of the Malir camp with great sadness, because the refugees were perfectly aware that it was to the aforementioned soldiers that they owed their survival from exile deep into the Soviet Union. In the meantime, the Poles were visited in Malir by both representatives of the Polish authorities and local notables, headed by the Viceroy of India, Lord Wavel. This was important support for them and always a major event in the camp. These special days were interwoven with orderly everyday life, in which there was room for both education and culture.

The first priority in organizing camp life was to start teaching. And so, Primary School No. 1 was established under the direction of Blanka Potocka. 300 children were enrolled in the institution, who were placed in nine classes, with one teacher per class. This school was located in one of the blocks, and a separate kindergarten operated at it. The school was equipped with desks and blackboards, but in insufficient quantities.

The only textbooks were those that the teachers had somehow saved with them during the deportation. Primary School No. 2 was located on the premises of the educational institution, occupying two of its blocks, and additionally blocks no. 126-134. It had 14 classes: four grades I, two each of grades II, III, IV, V and VI, and the first and second secondary school. The headmaster of this school was Zygmunt Ejchorszt, and there were 17 teachers there. The children in the institution came from the Isfahan orphanage, because many orphans came to India from Iran. This group lived together in the educational institution operating in the camp, where there were also orphans transferred from the Country Club. The children were eventually to be sent to the settlement in Balachadi. The secondary school classes were also attended by children from the Tehran group that appeared in Malir.

The educational institution itself was a separate unit in the camp and, for example, according to the May statistics of the Registration Department (from 1943), 1,098 children lived in the camp, including 575 orphans (there were 1,101 adults at that time), because not only orphans and half-orphans found shelter there, but also children who had both parents, but for various reasons were outside India or somewhere else on the subcontinent. The age of the children in the institution ranged between 3 and 19 years, boys made up a fifth. The institution housed full or half-orphans rescued from the USSR. They were cared for by seven educators, with the older children taking care of the younger ones, trying to create the most family atmosphere possible.

The second kindergarten in the camp was opened at Primary School No. 2. The teaching staff was insufficient for the needs of the camp; it was not possible to open a separate junior high school or high school. In order to stop the inactivity of the youth, who had already started their education in junior high school in Poland, the Cultural and Educational Department organized lectures for them on literature, history, geography and a number of encyclopedic knowledge. The speakers were: Michał Chmielowiec, Witold Bidakowski, Zygmunt Łopiński, Father Leopold Dallinger, Father Zygmunt Jagielnicki, Dr. Leon Koziełkowski, J. Banasz. The topics of the classes included, among others, issues from history, geography, the works of Henryk Sienkiewicz, or Bolesław Prus, theatre, literature, physics… It was not until June 22, 1943, that a group of junior high school teachers from Iran arrived at the camp. Work was immediately started on organizing a junior high school and a high school under the direction of Zdzisław Żerebecki. Registration was immediately announced and the new school year of 1943/1944 began just four days after the arrival of the teachers. 10 classes with 12 teachers were established, seven of whom were not qualified to teach in secondary education. 285 students were registered for the junior high and high school classes. However, there was a lack of all school supplies, especially textbooks for learning Polish, so a detailed request was sent to the Polish authorities in Bombay.

Children, in addition to studying, also organized themselves in other initiatives, in which scouting enjoyed wide interest. Two scout teams were formed in the camp: two boy teams, under the care of Scoutmaster Witold Bidakowski, and three girl teams under the care of Irena Świątkowska. There were therefore 28 scouts and 42 girl scouts in Malir in total. They received a Scout Chamber for themselves, equipped with games, maps, and the camp magazine issued them with material for uniforms sewn in the camp sewing room. As mentioned, the youngest – as part of scouting, but also outside of it – participated in various cultural events and (in various roles) in events and celebrations on the camp grounds and outside of it: in performances, shows, parades… Children from Primary School No. 1 gave, among other things, an artistic performance with singing for patients in a hospital in Karachi, where Polish refugees requiring more specialized help and medical care than the camp hospital or the one operating in the nearby Country Club could provide were also sent. Polish children also performed in a camp for American soldiers.

The Cultural and Educational Department operating in the Polish transit camp issued primarily a daily communiqué with news from the front lines, a review of Polish and world political events based on the Polish press and English radio. This often resulted in a great response among Poles. This was the case, for example, after the aforementioned announcement of the death of General Władysław Sikorski (then Prime Minister of the Polish government in exile) in a plane crash, in which he was returning from a several-week inspection of Polish forces in the Middle East. Upon hearing the tragic news, the camp residents hung out mourning flags, and many people put on black armbands, and a special service was also held. Polish refugees also participated in similar events outside the camp, for example the news of the Allied victory over the German forces in Tunis was celebrated in Karachi first with an Anglican service and later with an enthusiastic procession through the city, in which scouts and many other children (in Polish folk costumes) from the camp in Malir took part.

A frequently visited meeting place was the Cultural and Educational Department’s community centre. It was attended by an average of around 250 people per day. It was relatively well-equipped. The first purchase made for it was a radio, then a piano. Acquiring the piano enabled the organisation of music lessons and was used for musical illustrations during theatre performances and academies. It is worth noting here that there was a theatre group in the camp that remembered children above all: for example, Alicja Kisielnicka and Irena Świątkowska prepared two fairy tales for the stage: “Cinderella” and “Hansel and Gretel”, and for adults a performance of “The Post-Christmas Mazurka”.

The community hall, designed for 400 people, was full every time plays were performed. The community hall also had a gramophone, 49 records and books, which formed the beginning of a future library that was to be organized. The community hall reading room contained Polish periodicals (although outdated, always enjoying considerable interest), as well as illustrated English magazines. In addition, various games, including chess and cards, were used for entertainment purposes.

The social life of refugees was also filled with sports. Its enthusiasts, mainly young people, organized a sports club, within which there were two teams playing volleyball and football. The competition attracted not only active participants, but also many fans.

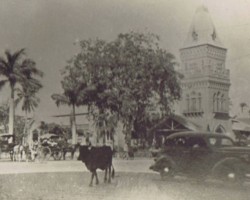

The Poles also enjoyed group trips to Karachi, for which passes were required, because police regulations in force in India did not allow people without visas to stay outside of designated places, in this case outside the refugee camp. For this reason, escorts with visas and permission to escort were sent with the Poles. These people were paid by those going to the city and acted as guides around it.

In such circumstances, life in Malir went on slowly, while the refugees awaited their fate and departure from the transit camp to other centers for Poles, both in India and in other countries of the world.

An important place for Poles to stay in India was the health resort in Panchgani. The British, ruling in India – in their colony, discovered this place and its properties in the 19th century. The first to recognize the benefits of Panchgani was John Chesson in 1850, 13 years later, thanks to the then governor of Bombay, it was discovered by Sir Hartley Frer. At that time, however, it was already a famous place where lung diseases were treated.

Panchgani, situated over 200 km south of Bombay and about 100 km from the city of Poona, at an altitude of 1,380 metres above sea level, surrounded to the north by the Krishna Valley and to the south by the Yenna Valley in the Sahyadri Mountains, was an excellent location for treatment. The journey from Bombay to Panchgani took eight hours: four by train to Poona and another four by bus on a road that twisted and turned just above the precipices. The climate of Panchgani was relatively cool and dry, the weather completely free of mosquitoes. The temperature during the hottest period did not exceed 36 degrees Celsius. The vegetation was lush, the monsoon rainfall was small. The villas, arranged on different levels, were immersed in the greenery of the trees.

The beginnings of Panchgani were modest; first, only six houses were built there and the village was inhabited by about 200 people.

In time, it grew into a city of three thousand people, built up with villas of very wealthy people – Indians and Europeans. They spent the summer months there, leaving Panchgani for the monsoon season. In addition to private homes, the city housed several boarding schools for girls and boys, but above all sanatoriums treating tuberculosis. The conditions for this were excellent.

The first Polish refugees from the Soviet Union arrived in Panchgani from a temporary centre in Bandra near Bombay, where the first of three Polish Red Cross transports with Polish children brought to India from Ashgabat stopped on their way to Balachadi. Among the six people sent to Panchgani was Hanka Ordonówna (real name Maria Anna Tyszkiewicz, née Pietruszyńska), who was increasingly feeling the effects of her hard labour in exile in the USSR (she worked as a forced labourer on the construction of a railway in the Uzbek SSR). Together with five children, she was sent as their carer to a sanatorium for treatment, and soon after this group was joined by others (not only the youngest children were sent to the centre, but also adults, mainly to improve their health, but sometimes also because they needed a longer rest after the physically and mentally exhausting period of exile in the Soviet Union and after the arduous journey through Iran to India).

All the children who were treated in Panchgani were “pulled out of school” by the Soviets and deported in the years 1940-1941, so in 1942 they had already had a two-year break in education. In the Bel-Air sanatorium, which the Poles had been given at their disposal by the authorities, they found Jan Sytnik, a professional teacher, who took care of their education. Soon, a second qualified teacher appeared in Panchgani – Maria Mitro. However, reality showed that due to the range of children’s ages, their health and the different levels of education to date, they could not be included in normal school classes, which is why a regular primary school was not organized, and only group teaching was practiced. In time, it was not until December 1944, after more children had arrived for treatment, that the Polish authorities in India established a primary school, operating in the normal mode. In the 1944/1945 school year, the school had 56 children studying in six classes. However, it turned out that the health of the youngest did not allow for such organized education in the long run, so modifications were made, transforming the classes into the General School Course. In 1946, the course had 45 children. At the same time, the Junior High School Course was established, with four classes and 11 students. The expanded and changed teaching staff at that time consisted of: Antonina Dzięglewska – head of the General School Course, Apolonia Najdzicz and Jan Sytnik. In addition to them, at various times – apart from the above-mentioned Maria Mitro – Helena Asłanowicz and Maria Wierzbicka also taught.

The courses operated within the Social Welfare Centre, established in 1943 by the Polish Delegation of the Ministry of Social Welfare and Assistance, whose employees saw the need to organise a place for their compatriots where they could recover after the dramas of exile in the USSR. The choice fell on Panchgani (where the first Polish refugees, as mentioned, had been sent earlier – since 1942).

Meanwhile, teaching children in sanatorium conditions was different from normal. It required much more from teachers, who had to cooperate with doctors taking care of young patients. In relation to sick students, only short-term school classes that did not absorb the child’s mind much could bring success. Despite this, education brought positive results, although the majority of the time of Polish children in Panchgani was taken up by the treatment of chronic diseases, mainly tuberculosis. Education in Panchgani ended with the liquidation of the Polish Social Welfare Centre in April 1947. The children then left for the Valivade settlement and, to the extent of their health possibilities, joined the local schools.

The sick – children and adults – undergoing treatment in Panchgani had little or almost nothing to contribute in the area of cultural group entertainment. This was made up for by Polish girls studying in the local St. Joseph’s Convent run by the Daughters of the Holy Cross order. Young Polish women were eager to show foreigners at least a bit of the folklore of their homeland, as there was a large group of young women in Panchgani who wanted to improve their knowledge of English. This need had long been noticed by the local Polish authorities, who placed groups of students with more advanced language skills in English schools. Only a few girls stayed in Panchgani for health reasons, most were sent there from the Valivade estate for a year, after the so-called small matriculation exam, after which they returned to Valivade for the second year of high school, leading to the Polish matriculation exam. It is worth mentioning that for the high school graduates from 1945, the nuns opened a special class with a trade profile. And in addition to studying, Polish students provided the residents of Panchgani with cultural entertainment, organizing concerts, academies and shows, both at the school, the Social Welfare Center for Poles, and the health resort itself. Ergo – these events enjoyed great success not only with Polish viewers. When in 1944 engineer Jan Pacak from the Polish authorities in India came to Panchgani for a vacation, a group of girls prepared a performance called “Wesele krakowskie” based on the most popular folk songs.

Pacak stayed in Panchgani permanently, he was appointed cultural and educational officer, from then on he led the choir in the convent, organized academies and intensively rehearsed the ensemble of “Wesele Krakowskie”, which was performed in Bombay, Kolhapur, Valivade, Poona and Mahableshwar. Since the performance was very popular everywhere, the project included further trips, which, however, did not come to fruition. Of the other plays, “Cinderella” and “Gondoliers” were performed. Interestingly, in the Polish folk dances, the boys were played by tall and slender girls (the main roles in “Wesele Krakowskie” were played by: Maria Wawrzynowicz as the bride and Teresa Orzechowska as the groom, while in “Cinderella”: Alina Suchecka in the title role and the aforementioned Teresa Orzechowska as the prince), and for some performances the props were prepared in the housing estate in Valivade. The participation of young Polish women in concerts and other events organized by the convent was always applauded. The great festival organized on May 30, 1946, prepared by the residents of the Social Welfare Center and the students of the St. George Convent, was particularly noteworthy in this respect. It was enriched by dances by children and girls, a raffle, and an artistic exhibition of handicrafts by women and young women from the center. It attracted a lot of interested people, for whom it was a real event in the orderly everyday life in the health resort in Panchgani.

Similar convents operated in other places in India: in Mount Abu, Karachi and Bombay. Thanks to the education provided there, Polish youth (girls and boys) could improve their English skills, but also in other areas of education. At the same time, their religious awareness was raised, because the convents were run by Christian religious congregations (male and female).

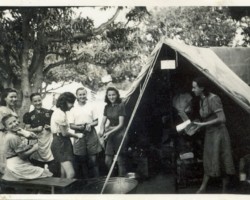

![Teresa Kurowska and Renata Żelichowska with "American Poles" in the Malir[?] transit camp near Karachi, 1944; source: Poles from India Association Teresa Kurowska and Renata Żelichowska with "American Poles" in the Malir[?] transit camp near Karachi, 1944; source: Poles from India Association](https://kresy-siberia.org/wp-content/uploads/cache/2025/02/2-m-t-kurowska-and-renia-zelichowska-with-poles/765109724.jpg)

![From the left: Aleksander Klecki, Joanna Chmielowska, Jan Pacholski after artistic performances in the Malir [?] transit camp near Karachi; source: Poles from India Association From the left: Aleksander Klecki, Joanna Chmielowska, Jan Pacholski after artistic performances in the Malir [?] transit camp near Karachi; source: Poles from India Association](https://kresy-siberia.org/wp-content/uploads/cache/2025/02/3-m-a-klecki-j-chmielowska-and-j-pacholski/1330169624.jpg)

Hanka Ordonówna – a singer, dancer and actress, a legend of the interwar period – her real name was Maria Anna Tyszkiewicz, née Pietruszyńska. She was born in Warsaw on September 25, 1902. When she was six, she began studying at the ballet school at the Grand Theatre, where she made her debut as a dancer in the 1915/1916 season. Soon, the very stressed, slim girl with blonde braids was hired to work for the “Sfinks” cabaret. She adopted the stage name Anna Ordon. She performed in “Czarny Kot” in Lublin and in the Contemporary Theatre in Warsaw. After an unsuccessful singing debut in the capital’s “Sfinks” theatre, she left for Lublin, where she was hired to work for the “Wesoły Ul” theatre. Soon she was singing and dancing again in Warsaw’s “Miraż” and “Sfinks”. During the Polish-Bolshevik war she found herself on the front line, where she worked in the Red Cross. Then came the difficult years of performances in Kraków, Vilnius, Lviv. She returned to Warsaw and in May 1922, thanks to the recommendation of the poet Zofia Bajkowska, she permanently joined the best Warsaw cabaret of the time, “Qui Pro Quo”, which was a turning point in the life of the young artist. The Hungarian compere and director Fryderyk Járosy, who was in love with her, became her artistic guardian. He created a great star. Thanks to him, she was able to study in Paris with the actress of the Comédie Française Cécile Sorel and the “diseuse de fin de siécle” Yvette Guilbert. After returning from France, she became a leading artist of “Qui Pro Quo”, she sang in a trio with excellent and famous singer, film, theatre and cabaret dancer Zula (born Zofia) Pogorzelska and Mira (born Maria) Zimińska, later co-founder and director of the “Mazowsze” group, and in the interwar period an actress of theatres and cabarets. Later she performed in “Banda” and also “Cyrulik Warszawski”. The lyrics were written for her by Marian Hemar (born Jan Marian Hescheles – Polish poet, satirist, comedy writer , playwright, translator of poetry, author of song lyrics from Lviv), Jan Lechoń (born Leszek Józef Serafinowicz – poet, prose writer , literary and theatre critic , co-founder of the poetry group Skamander ), Julian Tuwim ( poet , writer, author of vaudevilles, sketches, operetta librettos and song lyrics). She gave individual song evenings, concerts and recitals in all major cities of Poland, performed abroad: in Paris, Vienna, Rome, toured Palestine, Egypt, the United States and Germany. She performed in operettas, vaudevilles, revues. She played in drama theatres, including Viola in Twelfth Night alongside Juliusz Osterwa and Kasia in The Taming of the Shrew. She also became a film star, starring in “Niewolnica miłości”, “Orlęcie”, “Parada Warszawy”. In “Szpieg w maskce” she sang her most famous hit “Miłość ci wszystkopowiedzy”.

Hanka Ordonówna – a singer, dancer and actress, a legend of the interwar period – her real name was Maria Anna Tyszkiewicz, née Pietruszyńska. She was born in Warsaw on September 25, 1902. When she was six, she began studying at the ballet school at the Grand Theatre, where she made her debut as a dancer in the 1915/1916 season. Soon, the very stressed, slim girl with blonde braids was hired to work for the “Sfinks” cabaret. She adopted the stage name Anna Ordon. She performed in “Czarny Kot” in Lublin and in the Contemporary Theatre in Warsaw. After an unsuccessful singing debut in the capital’s “Sfinks” theatre, she left for Lublin, where she was hired to work for the “Wesoły Ul” theatre. Soon she was singing and dancing again in Warsaw’s “Miraż” and “Sfinks”. During the Polish-Bolshevik war she found herself on the front line, where she worked in the Red Cross. Then came the difficult years of performances in Kraków, Vilnius, Lviv. She returned to Warsaw and in May 1922, thanks to the recommendation of the poet Zofia Bajkowska, she permanently joined the best Warsaw cabaret of the time, “Qui Pro Quo”, which was a turning point in the life of the young artist. The Hungarian compere and director Fryderyk Járosy, who was in love with her, became her artistic guardian. He created a great star. Thanks to him, she was able to study in Paris with the actress of the Comédie Française Cécile Sorel and the “diseuse de fin de siécle” Yvette Guilbert. After returning from France, she became a leading artist of “Qui Pro Quo”, she sang in a trio with excellent and famous singer, film, theatre and cabaret dancer Zula (born Zofia) Pogorzelska and Mira (born Maria) Zimińska, later co-founder and director of the “Mazowsze” group, and in the interwar period an actress of theatres and cabarets. Later she performed in “Banda” and also “Cyrulik Warszawski”. The lyrics were written for her by Marian Hemar (born Jan Marian Hescheles – Polish poet, satirist, comedy writer , playwright, translator of poetry, author of song lyrics from Lviv), Jan Lechoń (born Leszek Józef Serafinowicz – poet, prose writer , literary and theatre critic , co-founder of the poetry group Skamander ), Julian Tuwim ( poet , writer, author of vaudevilles, sketches, operetta librettos and song lyrics). She gave individual song evenings, concerts and recitals in all major cities of Poland, performed abroad: in Paris, Vienna, Rome, toured Palestine, Egypt, the United States and Germany. She performed in operettas, vaudevilles, revues. She played in drama theatres, including Viola in Twelfth Night alongside Juliusz Osterwa and Kasia in The Taming of the Shrew. She also became a film star, starring in “Niewolnica miłości”, “Orlęcie”, “Parada Warszawy”. In “Szpieg w maskce” she sang her most famous hit “Miłość ci wszystkopowiedzy”.