Quick Links

Valivade – Education

The organization of schooling for Polish refugees in India was one of the most important problems faced in connection with the evacuation of former exiles from the Soviet Union to the subcontinent. After the disastrous years of Soviet occupation in the Eastern Borderlands for the education of the youngest and after the nightmare of exile, the school was to become for them not only a return to the path of education, but also a forge of character and a source of patriotism.

Unlike the transit camps, Valivade was built with a longer stay in mind, and the buildings designated for education were prepared for this purpose. However, these were the same temporary buildings as the residential blocks: stone foundations, walls made of bamboo mats on a skeleton of wooden beams, roofs made of red tiles, but without ceilings, only the windows, instead of shutters made of mats, had frames covered with canvas. The long blocks were divided into classrooms by thin bamboo walls, which “let the sound through” and the more undisciplined class often disturbed their neighbors during their lessons. Along each building there were arcades – verandas entwined with bindweed, where one could stretch one’s legs during breaks. The scorching sun did not encourage going outside. Only morning gymnastics took place between the blocks, because at that time it was still cool. Then, too, there were rare meetings of the whole school, also in the open air due to the lack of large halls. The furniture consisted of simple wooden tables, with a hole for an inkwell but no drawers (notebooks had to be kept on the floor), and also a blackboard and a stand for maps. In narrow beds along the blocks, the more economical schools grew plants: those shady morning glories, fiery-coloured cannas, an occasional papaya or banana tree.

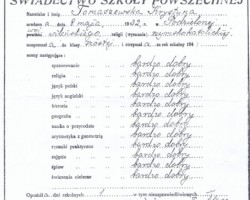

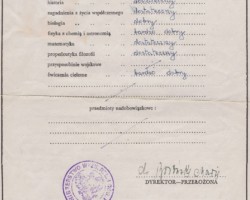

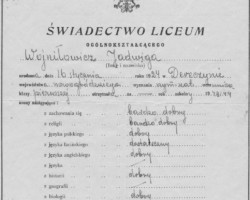

The structure of schools and their curriculum, exams, grades, and certificates were based on pre-war Polish models, but the calendar division of the school year into semesters had to be adapted to the requirements of the climate. The school year began on June 15, with the monsoon, which brought relief from the heat, and ended on March 31. The so-called big holidays, when the temperature reached 40 degrees Celsius, were eagerly spent by young people in Panhala or Chandola, mountain towns with a milder climate. Easter, a “movable” feast, sometimes fell on an unfortunate day – Holy Week, with retreats and adoration of the arranged Holy Sepulcher, had to be organized at a scout camp, and the return to the family had to be organized on Holy Saturday. On the other hand, the mass at the beginning of the school year was inevitably combined with getting wet on the way to church. But after two months of hot drought, the students welcomed the monsoon heralding the entire monsoon period with joy. Short holidays – two weeks in October – less hot, were good for course-camps.

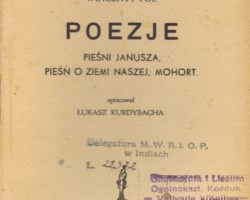

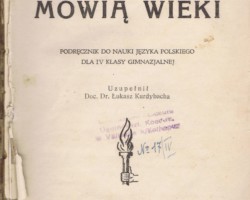

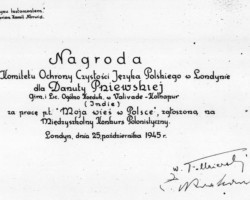

The problems faced by schools in the transit camps were slowly solved by Valivade. Although the flow of young people decreased and the teaching staff stabilized, the lack of qualified teachers, books and teaching aids was still noticeable. At first, single pages of the few textbooks that teachers or students had somehow brought with them and saved were copied on a mimeograph machine or even handwritten. Later, pre-war textbooks began to arrive, reprinted by publishing companies in England or by the Regulations and Publishing Commission of the Polish Army in the East, in Jerusalem. Thanks to the efforts of the wife of the governor in Karachi, Lady Dow, it was possible to reprint several items in India in 1943, later by the Delegation of the Ministry of Religious Denominations and Public Enlightenment in Bombay. Gradually, supplies increased, libraries were established, and one could take a book home instead of listening to it read aloud in the common room; one could learn from a textbook, not from notes taken in class. But until the end of the refugees’ stay, some textbooks, e.g. Polish-English dictionaries, were rationed, often shared by several students, and each new item in the library was a sensation, snatched from each other’s hands and passionately discussed.

The School Inspectorate worked on the Valivade estate throughout its existence. It represented the education system of the estate externally and was the voice of its needs before the MWRiOP Delegation in Bombay. The Inspectorate took care of all the general and vocational schools existing in the estate, and even, to some extent, supplementary courses organized by various institutions. It also maintained close contact with other departments, coordinating the activities of the schools with the overall needs of the estate. The establishment of the school inspectorate in Valivade was very necessary. In the initial phase of its existence, the Bombay headquarters took an active part in organizing education and scouting in the Valivade estate, but later difficulties related to political changes and the fight for finances removed it from these matters. The inspectorate, on the other hand, was on site, available to everyone and perfectly familiar with local problems. On September 1, 1943, Professor Zdzisław Żerebecki took up the function of inspector, but he retained his position as a lecturer in mathematics in the upper grades. Among the youth he was forever a “darcie”. Being at the same time the deputy delegate of MWRiOP, he had lively contact with both “the top” and his subordinates.

Elementary schools were established as children arrived in the settlement. On July 21, 1943, School No. 1 was the first to open. 103 children signed up and were divided into six classes. The teachers at the time were: Blanka Potocka, the headmistress, Father Leopold Dallinger, and four female teachers. The premises prepared for them had tables and chairs, but only one blackboard. Soon, more schools were opened.

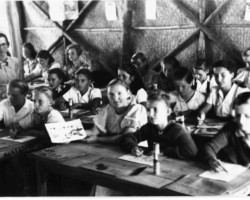

The teaching conditions were initially difficult. There was not enough school equipment, such as blackboards, teaching aids, and books. Teaching small children from notes they made is almost impossible. The teachers coped as best they could – instead of a blackboard, they wrote on sheets of cardboard, copied pages from individual textbooks they had, and produced their own school aids. However, teaching took place at a normal, or even accelerated pace, to make up for the children’s educational deficiencies caused by their wartime fate. The children were eager to learn, whether because they had had enough of the enforced inactivity during the wartime wanderings, or because they were able to appreciate the benefits of receiving education in Polish schools in their native language, something they had had a long break from, some of them since the Soviet occupation of the Borderlands.

By the end of the 1943/1944 school year the school equipment was completed, and teaching aids had also been added. Schools were equipped with maps, geographical atlases, globes, and natural history tables, some of which were made by students under the supervision of class teachers. The number of textbooks increased – in the second half of the 1943/1944 school year, there was an average of one textbook for every four students, but this situation was constantly improving. In March 1944, primary schools in Valivade obtained the rights of state schools. The following operated: School No. 1 named after Queen Jadwiga (in district No. 1), run first by Blanka Potocka (after she left on indefinite sick leave, Zofia Chrząszczewska became its head), School No. 2 named after Adam Mickiewicz (district No. 2) with head Antonina Harasymowa, School No. 3 named after Władysław Sikorski (at the General Władysław Sikorski Educational Facility) with its principal Olga Sasadeusz, School No. 4 named after Henryk Sienkiewicz (opened as the penultimate school in the 1944/1945 school year) with its principal Anna Chylowa (from July 1947 the principal was Helena Kurzeja) and School No. 5 – opened after the transfer of children from the gated housing estate in Balachadi to Valivade, in November 1946) with its principal Helena Asłanowicz. The staff of the schools changed, and a large number of teachers passed through them over the five years of their existence.

In addition to studying, school children took part in many extracurricular activities. Gardens were cultivated at schools, performances and trips were organized. Many children were members of scouts. The school organized at the General Władysław Sikorski Educational Facility was very active in organizing exhibitions and performances for the entire estate. Perhaps because the children there had fewer opportunities for individual entertainment, and living together – more opportunities for joint work, so they eagerly rushed to additional activities.

There were kindergartens at the public schools. Most mothers in the estate did not work for a living and could take care of their children, but some were employed in the estate offices, hospital or various workshops; there were also people who were unable to provide full-time care for their children for other reasons, so although initially there were five kindergartens in the estate (one in each district), over time there were fewer and fewer of them (in 1946 there were only three). Kindergarten teachers were paid like teachers in these schools and were organizationally subordinate to their heads.

In Valivade there were relatively few small children (this was due to: high mortality in the USSR, lack of natural increase due to separated marriages) and few older youth, especially males, because they were mostly in the army or in military schools: the Cadet Corps and the School of Younger Volunteers (SMO), popularly known as junaks and junaczki. On the other hand, there were many “average” children and it was necessary to find a place and an education program for them. A large part of the youth of secondary school age had to attend primary school due to lack of education, for the rest secondary schools were opened.

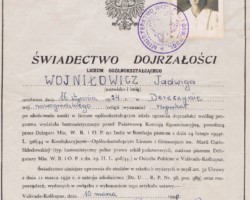

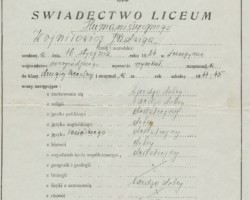

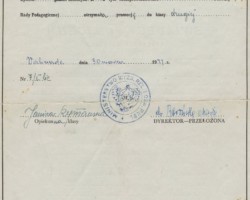

On August 19, 1943, the Maria Curie Skłodowska High School and General Secondary School began operating in Valivade. At that time, it had three first-year classes and two second-year classes, but soon an additional class was created, consisting entirely of youth from the General Władysław Sikorski Educational Institution. The school was managed by Dr. Maria Borońska (initially Zdzisław Żerebecki), and the origins of the institution date back to the stay of students and the organization of education in Camp No. 1 for refugees in Tehran (after the evacuation of Poles from the USSR to Iran), where three secondary schools operated. On June 15, 1945, the Stanisław Konarski Pedagogical High School was established in Valivade (at the request of the Delegation of the Ministry of Religious Denominations and Public Enlightenment). It accepted students who had completed four years of middle school and graduates of general high school. The principal was Maria Skórzyna, M.A. The program, shortened from three to two years, prepared students for the diploma of a primary school teacher. The same concern for providing young people with professional qualifications led to the establishment of the Karol Marcinkowski Merchant Junior High School at the general secondary school. At the beginning of the 1945/1946 school year, the first grade was opened with 38 students. The following year, the second grade and two first grades were established. This school was planned as a full merchant and trade junior high school, aimed at preparing a group of qualified trade and cooperative employees. Zdzisław Sikorski became the principal of the merchant junior high school; professors from other schools or specialists from the estate board taught there. Until the estate was liquidated, three generations of young people passed through the junior high school.

All secondary schools worked in a certain symbiosis – they shared not only modest resources and teaching aids, but above all the teaching staff, some of whom worked at both schools. However, when young people resettled from transit camps near Karachi began to reach these schools, the teaching staff had to be additionally expanded by teachers from elementary schools.

The issue of higher education was a major problem. Given the hostility of the English authorities, the poor English skills of graduates and financial difficulties, it was not possible to place our students in Indian universities. The project of sending them to study dentistry and veterinary medicine in Edinburgh also failed to materialise. Almost all the graduates of the first matriculation exam found employment as teachers in primary schools. The second batch in 1945 was partially absorbed by the estate administration. Only after the third matriculation exam was it possible to send a group of graduates to Bombay to study art and to a secretarial school, and in Panchgani a commercial course was organised for them. In 1946 a sanitary course was also organised in the estate, during which a dozen or so graduates obtained a diploma of the Polish Red Cross with the right to work in a hospital. After the matriculation exam in March 1947, they were “almost certainly” to obtain places at the University of Madras, but the political situation and the anxiety in connection with the approaching departures from India thwarted these plans. Such problems continued…

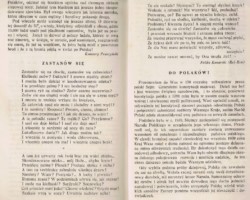

In addition to classes, children and young people attended other classes organized by interest groups. There was a literary group, which mainly included students of junior high and high school age, a geography group, and Polish Red Cross groups, where, among other things, first aid was taught to the injured, and a letter-writing campaign was held to Polish soldiers.

In addition to regular education, Valivade also offered education within the framework of various types of courses and vocational training. The issue of acquiring a profession became extremely important, especially in the context of the increasingly obvious prospect of permanent emigration and staying abroad, rather than leaving for communist Poland, for many refugees. And so the following were established in the settlement: the Stanisław Staszic School of Rural Farm Instructors (which also had its own experimental farm for practical classes), the Rural Farm Specialization Course, the School of Workshop Metal Craftsmen, the Journeyman-Master Tailoring School. There were also special vocational training courses, including knitting, cutting and sewing, typesetting and printing, nursing, and motor-car training for future drivers.

Five years of education in Valivade gave relatively high results. Almost 100 people were prepared for the Matura exam. Matura certificates obtained in India were later recognized in Poland and sometimes in countries to which Poles emigrated. They entitled them to apply for admission to higher education. Completed courses helped in finding a job, although sometimes at a lower level than the acquired skills would indicate. But most importantly – education in India gave a chance to develop national awareness and patriotism in the young generation of refugees, very important both for people who returned to Poland from India and for those who permanently remained outside the borders of their homeland.