Soviet Mass Deportations – April 1940

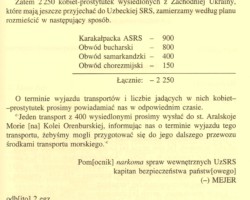

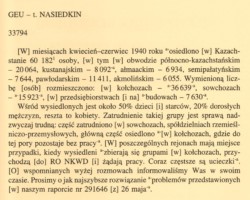

Exhibition Menu

Facts

Information

Exhibition Creator

Curator: prof. dr hab. Daniel Bockowski

Author: Prof. Dr hab. Daniel Bockowski

Queries: Michał Bronowicki (iconography, documents, photographs, memories and accounts)

Cooperation: Martyna Rusiniak – Karwat

The history of deportations of Poles to Siberia throughout history - Prison of Nations

Exile as a form of punishment existed in Russia from the beginning of the 16th century, although the destination of exiles at that time was not Siberia in today’s geographical sense. It is necessary to distinguish between deportations, deportations and expulsions to Siberia and “to Siberia”.

In the first case, we are talking about exiles and deportations to areas stretching from the Urals to the Kolyma River, including Krasnoyarsk Krai and Yakutia, bounded to the north by the Arctic Ocean, and to the south by the territories of Kazakhstan and Mongolia. If we take into account the postulates of researchers, including Russian ones, that the Far East is included in Siberia, then its eastern border will be the Pacific Ocean. However, for the historical and geographical description of Siberia, we will stay at the border on the Kolyma River. According to the administrative division from the period of tsarist Russia, these were the lands of the Tobolsk, Tomsk, Yenisei and Irkutsk governorates as well as the districts of Zabaikal, Amur, Yakut and Seaside. Using today’s administrative division, mostly in force during the deportations of the 1930s and 1940s, Siberia includes: the Republic of Yakutia (Sakha), the Republic of Buryatia, Republic of Tuva, Republic of Altai, Republic of Khakassia, Altai Krai, Krasnoyarsk Krai, Zabaykalsky Krai, Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug – Yugra, Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug, Tyumen Oblast, Omsk Oblast, Novosibirsk Oblast, Tomsk Oblast, Irkutsk Oblast and Kemerovo Oblast. All these areas, excluding Yakutia, are today part of the Siberian Federal District.

In the case of the historical concept of “Sibir”, we are dealing with exiles to practically all provinces and districts of the Russian and Soviet empires, including the previously mentioned lands of the Caucasus, Transcaucasia, the steppes of Kazakhstan, the Urals with the Sverdlovsk, Chelyabinsk and Perm regions, and the Republic of Bashkortostan, the Republic of Komi, Arkhangelsk region and Turkestan.

Another issue is the legal nature of the 16th-19th century exiles. There have never been uniform and clearly defined documents or tsarist regulations regarding exile as a form of punishment. From the very beginning, one of the most important purposes of the exiles was their “colonizing” character. The tsarist empire expanding to the east needed people to work and one of the ways to get them was forced deportation. Officially, this was not treated as a typical punishment for a crime, although this form of repression had all the hallmarks of it. The situation changed in the 18th century, and in 1822 the issue of exiles was regulated in a special act. By that time, there were more than 200 different types of legal acts in the tsarist legislation dealing with the criminal and economic aspects of exile. Formally, the term “exile” appeared in tsarist legislation in 1582 and was undoubtedly a means of repression. There were various types of punishment: sent to prison, sent to settle in a city or a selected settlement, sent to perform service (civil, spiritual and military) or to cultivate the land. Since 1649, all these categories of exiles have been included in specific legal norms. At that time, there were two main categories of criminals – the state and the state. In the eighteenth century, these differences disappeared, and from that time, exiles concerned political criminals. It is also worth mentioning that from the second half of the 17th century, criminal criminals sentenced to death, money counterfeiters with their families, people accused of “vagabondage”, theft and “suspicious contacts” were sent to Siberia. Peasant families soon found themselves among the deportees.

The first Poles found their way deep into Russia at the end of the 16th century, as a result of the war between the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and Moscow during the reign of King Stefan Batory. 50 Polish prisoners of war were used to build Tara, a city located on the left bank of the Irtysh River, 302 km from Omsk. Others went deep into the tsarist empire after the so-called Polish intervention in Russia during the “great trouble” at the beginning of the 17th century, when Polish forces under the command of Hetman Stanisław Żółkiewski occupied Moscow for two years. We do not know how many exiles there were at that time, nor do we know if they were all Poles. It is known that in 1617 (during the Polish-Russian war that started in 1609 and lasted for the next nine years) 60 Poles and Lithuanians were sent “over the Urals”, who returned home after a few years. In the years 1614-1624, a total of several hundred prisoners were found in Siberia. In Russian documents, we often encounter the term “Lithuanian people”, which, however, does not clearly indicate the nationality of the exiled person, but rather the place of residence or residence before being taken into Russian captivity.

During the reign of the Vasa dynasty, after numerous wars between the Commonwealth and Russia, Russia and Sweden, and the battles for Ukraine, among dozens of Poles, most often prisoners of war, was the first Catholic priest known to us, Jędrzej Kaweczyński. He served his exile in Narym and Tobolsk, where in the first half of the 17th century there was certainly an unknown group of Poles.

The fate of the exiles most often depended on the place of deportation, their skills, level of education and chance. Thanks to literacy and specialist knowledge in a given field, many of them over time took up a number of positions in local administration and commerce. Some led research expeditions that penetrated the farthest regions of the tsarist empire, reaching the shores of the Pacific Ocean. We know the name of one of these explorers, exiled in 1621 – Samson Nowacki, who led a number of expeditions to the Lena and Yenisey. In turn, Adam Kamieński-Dłużyk, taken prisoner by the Russian army in 1660 on the Bania River, exiled to Kolyma, during his stay in Siberia reached the basin of the Lena River and the Amur. In the years 1664–1668, he also served as a prison supervisor in Yakutsk. Under the Andruszów truce of 1667 (ending the Polish-Russian war waged since 1658), he returned to Poland and described his stay in exile. In his The journal of the Moscow prison, cities and places contains the first geographical and ethnographic information in the history of Poland of this region of Siberia.

How many Polish POWs-exiles there were in the discussed period, little is known. Most likely, their number does not exceed several hundred. At the end of the 17th century, according to the data in the Russian archives, several thousand citizens of the Commonwealth lived in Siberia. Quite a large group settled voluntarily, looking for a place to develop their careers. Little is known about their nationality, although – as already mentioned – there were certainly Belarusians, Lithuanians, Ukrainians, and perhaps even Jews among them. These people, if they managed to survive the first, most difficult period of acclimatization, over time made considerable fortunes and worked at various levels of the Russian administration. A person about whom a little more is known was Paweł Chmielewski, which during the Dymitriads (two Polish military interventions in Russia during the “Great Troubles”, related to the plan to put successive candidates on the tsar’s throne claiming to be the son of the previous ruler – Ivan IV the Terrible, the first tsar in the history of Russia), which became one due to the Polish-Russian war that broke out shortly afterwards, in 1609, he went over to the Russian side in Moscow, for which he was handsomely rewarded. After some time, he was sent to Tobolsk for conspiring with the Poles in Smolensk. After a short stay in prison, he was released and laboriously climbed the career ladder in the Russian administration, reaching the position of commandant of Yenisiejsk in 1622, and then the inspector. Another well-known exile was Nicefor Czernichowski,

Not everyone was successful in exile. Harsh living conditions led to attempted rebellions and local uprisings. In the 1630s, Poles exiled to Tomsk and Tobolsk tried to provoke such a revolt, but it was bloodily suppressed. Returns from deportation under the peace treaties concluded by Russia and the Republic of Poland were a chance to improve their living conditions. However, the Russian authorities tried to persuade the Poles remaining in exile to stay, offering a number of concessions, promotions and pardons. From the point of view of the authorities, these actions were completely justified, as the Poles in exile mostly came from the nobility, so they had the education necessary for the efficient functioning of the local administration.

In the eighteenth century, not only the living conditions of exiles changed quite significantly, but also the scale of resettlement. In order to facilitate the flow of thousands of forced exiles-colonizers into the depths of the empire, special marching routes were marked out, staging points were created and settlement areas were strategically marked out. Before leaving, the exiles were gathered into groups, called parties, usually consisting of 150 to 200 people. The place of formation of such groups was Kaluga. From here, along the Oka and Volga rivers, exiles were delivered to Kazan. After creating further transports along the Kama River, they were sent to Nowy Usol. The next staging point was Wierchoturia, where people traveled on foot or rode in horse-drawn carts. Further, smaller batches of exiles were delivered by rivers to the assembly point – Tobolsk. Then, again by land, the deportees were driven to Tomsk, and from there to Irkutsk. in Irkutsk, based on the incoming demands from the local structures of the tsarist administration, people were sent to Okhotsk, the Far East, Kamchatka, Zabaikal and Yakutsk. The main rivers used for transport at that time were the Irtysh, Kama and Viluya. Due to the huge distances, many exiles died on the way as a result of disease, fatigue and punishment.

For those who arrived, it was no longer as easy to arrange a life as it was for the exiles from the 17th century. The tsarist administration was already organized, and the exiles were needed as cheap, hired labor. The legal nature of the shipment has also changed. The most severe sentence was lifelong exile and forced labour. People sentenced to life imprisonment were deprived of all political and state rights, and could never leave the place of forced settlement. A simpler form was simple exile and forced residence, similar to administrative settlements to which Poles were sentenced in 1940.

A new form of deportation was forced labour, probably best remembered in Polish historiography, which for many years was synonymous with exiles “to Siberia”. From the point of view of the tsarist authorities, it was the most efficient way to acquire and use slave labor in mines and special industrial plants. Convicts travelled to the place of deportation shackled on their hands and feet, often additionally attached to bars, beams and chains. Also in the case of this type of punishment, those sentenced to life imprisonment were deprived of all rights and remained at the disposal of the state until their death. The death penalty was almost always replaced with hard labor. Persons sentenced to hard labor for life were marked with letters burned on their bodies indicating the nature of the deportation (KAT, SK, K) before serving their sentence and subjected to brutal flogging,

Initially, hard labor was not associated with Siberia. Convicts worked in various European regions of Russia. The situation changed in the middle of the 18th century, when the demand for gold and coal mined in the mines of the Yekaterinburg and Nerchin districts increased. The first of them quickly declined in importance, while the second, located in the eastern part of the Zabaikal Oblast, became a terrifying place among convicts. Not only criminals worked in Zakłady Nerczyńskie, where silver was mined. A large group were the peasants sent there. There was also the Orenburg district in Western Siberia, but due to the relatively short distance from European Russia, it was not expanded.

The largest wave of Polish exiles arrived in Siberia in the second half of the 18th century, after the defeat of the Bar Confederation, established in 1968 (against Russian interference in the internal affairs of the Republic of Poland threatened with loss of independence and against the submissive Tsarina Catherine II, King Stanisław A. Poniatowski), although also in In the first half of this century, especially during the reign of Stanisław Leszczyński, a large group of supporters of the monarch were deported to the east. The Bar Confederates were the first group exiled for purely political reasons. There were about five thousand of them. They made their way through Kiev, Tula, Nizhny Novgorod, Kazan, Viatka, Perm, Yekatyrenburg to Tobolsk. From there they were sent to Irkutsk and the notorious Nerczynski Plant. They tried to force them into the army, however, it succeeded only in the case of a small group of rank-and-file soldiers from the nobility and the peasantry. The officers, for the most part, remained adamant. The most famous confederate (next to, among others, Kazimierz Pułaski – one of the commanders of the Confederate army and later a hero of the American Revolutionary War) was Count Maurycy August Beniowski, the author of extremely colorful memoirs reminiscent of the novel of a coat and sword, first sent to Kazan for anti-Russian speeches, and then then to Kamchatka, where he initiated the revolt of exiles and their escape from the peninsula. An interesting diary was also left by Karol Lubicz Chojecki, who was sent to Siberia for his participation in the Confederation, where he was forcibly conscripted into the Russian army, from which he escaped. Well-known confederates also include the Frenchman August Thesby de Belcour – exiled to Tobolsk, where he recorded his experiences. The Bar Confederates were released from exile under Catherine II’s order in 1773, but General Denis Chicherin did not carry out the order, sending only officers and invalids to Poland. The rest of the soldiers he recruited to the Cossack troops. He finally released them only in 1781, but about 90 people remained in exile voluntarily and made their lives there.

In the years 1794-1797, they were joined by the participants of the Kościuszko Uprising, aimed – in defense of Poland’s independence – against Russia and Prussia. In total, it was about 5-6 thousand people. The situation improved in 1796, when Tsar Paul I issued another order to free Poles. How many actually returned from exile at that time is unknown. It is known, however, that one of the most famous exiles of that period was General Józef Kopeć, the author of an interesting diary, first imprisoned in Smolensk, then exiled to Kamchatka, where he conducted valuable ethnographic research.

Subsequent groups of Poles found their way to Siberia during the partitions, as a result of the activities of the first secret conspiracy organizations, such as the Warsaw Central Assembly, the Patriotic Union operating in Lithuania, or the Union of Good Poles operating in Volhynia. Among those arrested at that time was Józef Bohusz, who went to exile with his wife. Perhaps she was the first Polish woman who voluntarily ended up in Siberia as a result of tsarist repressions. After 1815, most of the exiles were allowed to return. Only 160 people were drafted into the Cossack units. Nevertheless, after the defeat of Napoleon, who in 1812, having amassed a multinational army (including about 90,000 Poles), tried to conquer Russia, probably about 900 Poles were sent “to Siberia”.

During the existence of the formally autonomous Kingdom of Poland (established in 1815 after the Congress of Vienna – a great, two-year conference of 16 European countries), repressions on both sides of the “border” had a different character. Inhabitants of the “incorporated lands” wandered into exile on the terms applicable to all subjects of Tsarist Russia, while the inhabitants of the Kingdom, under the constitution given by Tsar Alexander I (adopted as a result of the decisions of the Congress in 1815, establishing a personal union between the Kingdom and the Russian Empire; from then on, the Tsar became at the same time the king of Poland) served their sentences on the spot. What mattered was the official entry in the population registers, not the place of residence. During this period, representatives of the Filomats and Filarets (conspiratorial patriotic associations of Vilnius youth) went into exile, people active in secret Russian circles and sympathizing with the Decembrists (participants of the anti-tsarist uprising in the 1820s). Among those deported, it is worth mentioning Count Mikołaj Worcell, sent to a penal company in the Caucasus, Anzelm Iwaszkiewicz, Seweryn Krzyżanowski – a member of the secret pro-independence Patriotic Society operating in the Kingdom of Poland and Piotr Moszyński – marshal of the Volhynian nobility, sent to Tobolsk for his underground patriotic activities. The situation changed in 1832, when the constitution of the Kingdom of Poland was abolished. However, since it was still impossible to formally send the citizens of the Kingdom deep into Russia, the institutions of “arrest squads” were used. Among those deported, it is worth mentioning Count Mikołaj Worcell, sent to a penal company in the Caucasus, Anzelm Iwaszkiewicz, Seweryn Krzyżanowski – a member of the secret pro-independence Patriotic Society operating in the Kingdom of Poland and Piotr Moszyński – marshal of the Volhynian nobility, sent to Tobolsk for his underground patriotic activities. The situation changed in 1832, when the constitution of the Kingdom of Poland was abolished. However, since it was still impossible to formally send the citizens of the Kingdom deep into Russia, the institutions of “arrest squads” were used. Among those deported, it is worth mentioning Count Mikołaj Worcell, sent to a penal company in the Caucasus, Anzelm Iwaszkiewicz, Seweryn Krzyżanowski – a member of the secret pro-independence Patriotic Society operating in the Kingdom of Poland and Piotr Moszyński – marshal of the Volhynian nobility, sent to Tobolsk for his underground patriotic activities. The situation changed in 1832, when the constitution of the Kingdom of Poland was abolished. However, since it was still impossible to formally send the citizens of the Kingdom deep into Russia, the institutions of “arrest squads” were used. Seweryn Krzyżanowski – a member of the secret pro-independence Patriotic Society operating in the Kingdom of Poland and Piotr Moszyński – the marshal of the Volhynian nobility, exiled to Tobolsk for his underground patriotic activities. The situation changed in 1832, when the constitution of the Kingdom of Poland was abolished. However, since it was still impossible to formally send the citizens of the Kingdom deep into Russia, the institutions of “arrest squads” were used. Seweryn Krzyżanowski – a member of the secret pro-independence Patriotic Society operating in the Kingdom of Poland and Piotr Moszyński – the marshal of the Volhynian nobility, exiled to Tobolsk for his underground patriotic activities. The situation changed in 1832, when the constitution of the Kingdom of Poland was abolished. However, since it was still impossible to formally send the citizens of the Kingdom deep into Russia, the institutions of “arrest squads” were used.

They appeared after the November Uprising directed against Russia (started in 1830 and finally lost after 11 months of fighting), although until 1836 they formally functioned outside the Kingdom of Poland. These were penal battalions where people were sent for crimes committed during military service. The convicts worked in military fortresses. If they were not soldiers, the punishment was called civilian recruitment. The rotations lasted from 5 to 15 years. Anyone who tried to escape or committed a crime during the service under the tsar’s order of 1834 could be sent to Siberia. It was on the basis of such laws that Poles fighting in the November Uprising were punished. The basis for the sentences was the Military Field Code of the great active armyfrom 1812. The insurgents were conscripted into rotas in Siberia, the Caucasus and the Urals, sent to the Arkhangelsk and Orenburg governorates, as well as to the “Kyrgyz steppes”, i.e. to today’s Kazakhstan. We do not know the exact number of those punished, but the surviving lists include 774 names.

In the period between the uprisings, other conspirators were sent “to Siberia”. The first was a group of about 100 people sentenced for participating in a conspiracy of Colonel Józef Zaliwski, a military man in the army of the Kingdom of Poland and an independence activist. For participation in the conspiracy, about 50 peasants from the Grodno and Minsk regions, as well as a group of priests, were sent east. There were several women among the deportees, including Marianna Karpińska. In 1838, nearly 100 people were sentenced to exile for participating in the conspiracy of Szymon Konarski – a former November insurgent and independence activist. Among them: Gustaw Ehrenberg – son of Tsar Alexander I, an activist of the Polish People’s Association, and Aleksander Wężyk (also a member of the Polish People’s Party, who together with Ehrenberg initiated the activities of the Association, previously founded in Galicia by Szymon Konarski). A year later, in Łomża, the group of Rafał Błoński – a lieutenant of the Polish army, who was sent to Siberia for 17 years for his underground activities for independence (he wrote a diary about it), was broken up in Łomża, from which he returned and took part in the January Uprising that broke out in 1863. 24 people were then sentenced to exile. Conspirators operating in the association of priest Piotr Ściegienny (organizer of independence movements), Galician insurgents from 1846 and 36 members of the organization of Henryk Krajewski from Warsaw (an activist of democratic conspiracies, exiled to the vicinity of Nerczyńsk) and many other underground organizations operating in the Kingdom of Poland and In Lithuania. Political emissaries and emigrants who secretly entered the Kingdom of Poland were also sent to exile, as well as people fighting during the Spring of Nations (a series of revolutionary social and national uprisings in Europe in the years 1848 – 1849). In total, about 600-800 Poles were sent to the East for political activity at that time, of which over 200 ended up in Siberia. Among them was a member of the National Government during the January Uprising started in 1863, a journalist and writer, Agaton Giller, captured in 1853 by the Austrian authorities and extradited to Russia. Sentenced to hard labor, he served in penal battalions in eastern Siberia. The result of his stay in exile were several works about exiles and Siberia published after returning to the country (e.g. Among them was a member of the National Government during the January Uprising started in 1863, a journalist and writer, Agaton Giller, captured in 1853 by the Austrian authorities and extradited to Russia. Sentenced to hard labor, he served in penal battalions in eastern Siberia. The result of his stay in exile were several works about exiles and Siberia published after returning to the country (e.g. Among them was a member of the National Government during the January Uprising started in 1863, a journalist and writer, Agaton Giller, captured in 1853 by the Austrian authorities and extradited to Russia. Sentenced to hard labor, he served in penal battalions in eastern Siberia. The result of his stay in exile were several works about exiles and Siberia published after returning to the country (e.g.Polish graves in Irkutsk ).

Before the November insurgents reached Siberia, under the tsar’s orders in 1822, the reform of Michał Sperański (a Russian lawyer and advisor to Tsar Alexander I) was passed. It made thorough changes in the structure of administering those who were in exile. The Tobolsk Office for Exiles and the local prison administration were established, which was to keep a register of exiles and ensure compliance with release dates. It was also supposed to take care of the distribution of exiles in the settlements and to provide them with the means of subsistence. For the first time, it was written that people should be paid for their work. The children of forced laborers were included in the category of free settlers. Complaints allowed. Staged prisons were built along the prisoner transport routes to facilitate checks by guards during stops.

The route of the deportees started in Moscow, from where they went on foot through Włodzimierz, Nizhny Novgorod, Kazan, Yekatyrenburg, Tobolsk, Tomsk, Krasnoyarsk, Irkutsk to Chita. River transport was used only on the stages from Nizhny Novgorod to Perm and from Tyumen to Tobolsk. In Siberia, the exiles had to go through a total of 61 stages. Men were going to Tobolsk in shackles.

The largest group of Poles was sent to hard labor and deportation after the January Uprising. In the years 1863-1867, more than 25,000 people went deep into European Russia, Siberia and the Caucasus. About 1,800 relatives went into exile voluntarily with them. Over 6,000 people were conscripted into prison rots. There were over 18,000 Poles in Siberia, which constituted over 32% of all deportees from all over Russia. 23% of Poles were sentenced to hard labor. At least 340 clergymen were among those repressed. In 1881, 270 people still in exile were counted.

The post-uprising period, although on a smaller scale, still abounded in various “streams and rivulets” of political exiles. In the course of one case, on average, a dozen, sometimes several dozen people were convicted. Among those sent deep into Russia at that time was Wacław Sieroszewski – a writer, recognized and supported by the Russian Geographical Society, the author of many ethnographic works about the inhabitants of Yakutia and the Far East, as well as Bronisław (an ethnographer describing the peoples of Sakhalin, where he ultimately stayed) and Józef Piłsudski. Increasingly, socialist activists associated with, among others, wandered to Siberia. with the “Proletariat” movement – a Polish political party based on the assumptions of Marxism and party-organizations continuing its ideas after the breakup of the group. In 1893, a dozen Polish and Jewish workers from Lodz were sent deep into Russia for planting a bomb. Among those convicted of revolutionary activities were Władysław Studnicki, Ludwik Janowicz and Jan Stróżecki (socialist activists, members of “Proletariat”).

The beginning of the 20th century brought an increase in exile penalties. The real breakthrough was the repression after the revolution of 1905. In the years 1901-1911 in the Kingdom of Poland, 3,153 people were sentenced to hard labor, and 258 to exile. In the years 1905-1910, about 10,000 people were sent to the east without court sentences, and in the next two years, another thousand people. The largest concentrations of Poles were in Tomsk, Omsk, Irkutsk, Krasnoyarsk, Nerczyńsk and Vladivostok. Large groups of Poles found themselves in Siberia during World War I. They were mainly forced displaced persons from war-torn areas, refugees (runners) and prisoners of war.

To this day, we do not have full information on how many people decided to voluntarily go to Siberia. Certainly, soldiers settled here after completing their service, if they got married during it, military doctors, civil servants, graduates of universities and vocational schools who had to serve education allowances. There was also considerable economic emigration. Most of them were engineers and mechanics leaving for the construction of the Trans-Siberian Railway. From the second half of the 19th century, this emigration began to gain momentum. The population from the lands of the Kingdom of Poland prevailed. The number of emigrants from “Kongresówka” (as the areas of the Kingdom of Poland were colloquially called) into Russia in 1910 was estimated at 400-600 thousand people. Most of the Poles who settled in Siberia were peasants.

Mass deportations to the USSR as an element of the sovietization of the Eastern Borderlands

Almost immediately after the Red Army troops entered the eastern territories of the Second Polish Republic on September 17, 1939, the repressive apparatus of the NKVD began to carry out its basic task, which was to take control of the plundered lands and break any forms of resistance against the new government in the bud. One of the most important goals was to organize an effective administrative and police apparatus responsible for the gradual sovietization of the occupied lands. On the so-called In Western Belarus and Western Ukraine, the formation of a new loyal Soviet citizen began. The slogans for the liberation of “the oppressed brothers of Ukrainians and Belarusians” turned out to be empty slogans. There was no question of any freedom, at most – for short-term propaganda purposes – Poles were ostentatiously pushed to the bottom of the social ladder,

In order to implement the program of sovietization of Kresy, it was first necessary to clear these lands of people who, according to the authorities, were the greatest threat. One way was mass deportation. They combined several important factors: political – getting rid of actual and alleged enemies, economic – obtaining hundreds of thousands of free hands for felling forests, building new railway lines and maintaining existing ones, and the security factor – intimidating the public in the occupied territories with the scale of repression to break any will to resist. The economic factor, although very important, especially in the case of the February deportation (carried out on February 10, 1940), was not the main reason for the repression. Also, the national character of repression in many cases gave way to the social goal – the elimination of potential enemies of the new order.

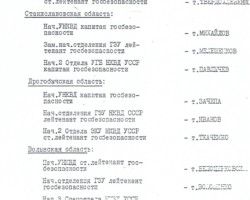

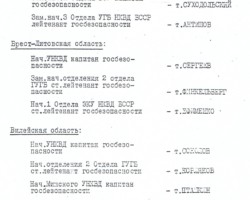

In the case of each deportation, decisions to carry it out were made at the highest levels of USSR state authority. The persons directly responsible for starting each large deportation action were Joseph Stalin, Lavrentiy P. Beria and Vyacheslav Molotov, as well as other members of the Council of People’s Commissars of the USSR (RKL USSR). In turn, the coordinators of the whole at the state level were the head of the NKVD (People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs) Lavrentiy Beria, his deputy Vsevolod N. Merkulov and the head of the Administration and Economic Directorate of the NKVD of the USSR Bakhcho Z. Kobulov. In the republics from which the deportations were carried out, the action at the republican level was coordinated by the heads of the NKVD: for the Ukrainian SRS – Ivan A. Serov, for the Belarusian SRS Lavrentij F. Canawa (properly surname Dzhanzhgawa).

Documents regarding the start date and course of each action were issued in Moscow well in advance, so that the best possible preparation could be made. Decrees regarding the February deportation were issued on December 4 and 5, 1939, and the April action – carried out on April 13, 1940 – March 3, 1940. The same regulation specified the course of the resettlement of refugees two months later. After the action was completed, detailed reports were sent to the coordination centers where they were analyzed, trying (usually unsuccessfully) to remove organizational shortcomings on an ongoing basis. Year after year, the Soviet repressive machine learned how to carry out mass resettlements in the most effective way and at the lowest cost. Initially, only politically uncertain groups, at the end of World War II – entire nations.

All displaced groups received a special status that determined their fate and the fate of their children for many years. Those sent by the Soviets in the 1930s (including Poles from Dzierżyńszczyzna in Soviet Belarus and Marchlewszczyzna in Soviet Ukraine, deported mainly to Kazakhstan) were referred to as trudposielency. During World War II, interchangeably, also as spiecposielency . According to the state of January 1940, this contingent consisted of 997,513 people, and in 1941 – 930,221. They were mainly peasants displaced as part of forced collectivization in the USSR. The deportees from the 1940s were classified into several groups:

- people deported in February 1940 were classified as spiecpieriesielency-settlers , less often as former Polish settlers and foresters ;

- those deported in April 1940 under the administrative-emissary category , although sometimes they were also referred to as spiecpieriesielency ;

- people deported in June-July 1940 were in the category spiecpieriesielency-runners ;

- people deported in the summer of 1941 (both from Western Belorussia and Western Ukraine, as well as from Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia and Moldova) were referred to as residing. The following terms are also used interchangeably in Soviet documents for this group: administrativno-ssylnyje and ssylno-pieresielency .

Only groups defined as spiecpieriesielency were directly under the control of the NKVD and were placed in special settlements ( spiecposiołki) . The second and fourth contingents were sent in administrative mode and were only under the careful control of the NKVD authorities, mainly in kolkhozes and sovkhozes.

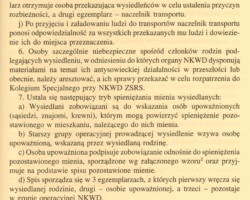

Classic deportation, also called deportation, deportation, forced displacement or resettlement in various sources, involved, according to the instructions, whole families cohabiting in one household or apartment. In practice, this meant that even if one of the residents was not on the lists for deportation, they were already on them during the operation. Cases of leaving such people in the house from which the deportations were carried out were rare. In exile, the legal status of children born from the union of parents assigned to a given contingent was inherited.

Preparations were made very carefully for each deportation. At least that’s what the documents that have survived to this day show. In the first phase, the planning of the action was carried out in Minsk and Kiev without informing the authorities of the western regions of the Byelorussian SSR and the Ukrainian SSR about everything. The documents found in Minsk show that the lists of people to be deported were prepared on the spot and only then sent to the occupied territories for initial verification. The verification took place in a very small group, with the greatest possible secrecy. After calculating the size of the presumed contingent, the data was first sent to the regional headquarters, and then to the commissions in Minsk, Kiev and Moscow coordinating the entire operation. Based on the presumed contingents of deportees, the demand for wagons to transport them, the convoy necessary for the operation and financial resources – for equipping the wagons, remuneration of participants in the action and possible provisions for the deportees on the way, were prepared. Guidelines were also sent to the relevant people’s commissariats in order to prepare for the reception, deployment and use of the delivered exiles.

The February and June 1940 deportations were to bring measurable profits to the NKVD in the form of fixed fees paid by individual people’s commissariats of industry for the use of the supplied labor. The exiles were de facto treated as “slaves on the market” because the NKVD conducted a kind of tender for the supply of forced laborers in accordance with the declared demand.

The directives of the NKVD in such actions were very detailed and regulated most of the events that could take place. Cases authorizing the convoy and the deportation trio to use force, including firearms, were carefully determined. Most of the ordinances were based on a repeatable pattern developed by the Soviet security apparatus during operations carried out in the 1930s. This is perfectly visible on the example of the deportation orders of December 1939 and March 1940, which in terms of the course of the action and the manner of proceeding are almost no different from each other.

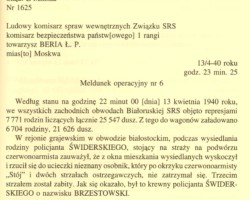

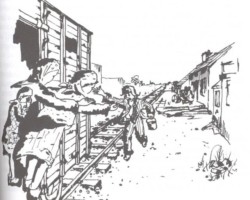

Deportations usually started in the middle of the night or at dawn. The exception was the deportation of refugees in June 1940, when the population was gathered gradually over the next few days, most often under the pretext of appearing to leave for the German occupation zone, which most of the deportees unsuccessfully tried to obtain. Operational groups, having received a list of persons to be detained, went with an armed convoy to the indicated addresses, woke up the designated families, put men (if any) against the wall to prevent any resistance, and then conducted a thorough search in order to detect weapons, ammunition, foreign currency and counter-revolutionary materials. They quite often used local activists as guides and translators. After the search was over, time was set for packing the most necessary things and the detainees were transported by horse-drawn carts to the places where deportation trains were formed. All persons who were in the house or entered it and who were not the deportee’s family were, as a rule, detained until the end of the action and, after explanation, eventually released. However, it was also the case that they were going to exile together with the rest of the detainees. After the exiles were taken out, the property they left behind had to be secured. After delivering them to the places of loading, the tasks of the operational teams ended, and the “care” of the people was taken over by the Convoy Troops of the NKVD. and who were not the family of the deported, were, as a rule, detained until the end of the action and, after explanation, possibly released. However, it was also the case that they were going to exile together with the rest of the detainees. After the exiles were taken out, the property they left behind had to be secured. After delivering them to the places of loading, the tasks of the operational teams ended, and the “care” of the people was taken over by the Convoy Troops of the NKVD. and who were not the family of the deported, were, as a rule, detained until the end of the action and, after explanation, possibly released. However, it was also the case that they were going to exile together with the rest of the detainees. After the exiles were taken out, the property they left behind had to be secured. After delivering them to the places of loading, the tasks of the operational teams ended, and the “care” of the people was taken over by the Convoy Troops of the NKVD.

Deportation meant, in practice, the loss of all one’s possessions. The instruction of the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs of the USSR of December 1939 on the order of resettlement of Polish settlers from the western regions of the USSR and BSSR provided for the right to take only 500 kg of belongings per family – most often clothes and basic household appliances. It also happened that the convoy did not allow to take almost anything. The property left behind became the property of the state. Before they were secured, many things were stolen by local residents and local communist party activists.

The “revolutionarily aware population” was already striving to get rid of the “Polish bloodsuckers” during the sessions of the People’s Assemblies of Western Ukraine and Western Belarus (at the end of October 1939). This was also done by the chairman of the WKP(b) of Belarus – the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) of Belarus – Pantalejmon K. Ponomarenko, who at the beginning of December 1939, in a letter to J. Stalin, stated, inter alia: argued the need for quick action: “[…] these farms have a minimum of 35-40 ha of land, 3-4 and more horses, only in very rare cases 2 horses, 5-6 and sometimes 10 and more cows, in very rare cases only 2-3 cows. The settlers’ farms have significant stocks of grain, which cannot be ascertained today. However, it should be emphasized that many settlers’ farms contain grain not only from but even from 2-3 previous years”. He also wrote about the plows, harrows and other small tools owned by the settlers, as well as large amounts of modern agricultural machinery. About the fact that every household has at least one bicycle, and many have 2-3 bicycles and even motorcycles.

According to Ponomarenko, over 200,000 hectares of excellent arable land and meadows would be obtained in this way, which could be distributed among the poor and the first model kolkhozes could be created on it. The 30-40 thousand cows that the settlers supposedly had had to be distributed to the poor. 15-20,000 settlement horses (“strong and well-fed”) could be used for the needs of the Red Army, cavalry militia, District Executive Committees ( Rajonnyje Isponitielnyje Komitiety, Raispolkomy) and the Border Guard, and give the rest to the rural poor. In large, brick houses, he argued, schools, commune councils, shops, medical facilities, militia stations and reading rooms could be located. Small agricultural equipment will be distributed to the local peasants, while the machines obtained in this way will be used to create Agricultural Machinery Centers ( machine-tractornye stancyi, MTS). Large quantities of excellent seed, winter crops and grain for milling were taken away from the settlers to help organize the sowing in the spring. The Peasants’ Committees had to be given away the household belongings left by the displaced, while bicycles and motorcycles had to be handed over to the local authorities for official purposes. In short, the deportation of settlers and foresters was supposed to solve many pressing economic and provisioning problems of the new government.

The first stage of preparation was Beria’s letter to Stalin of December 2, 1939, about the need to immediately remove all settlement families from the western regions of the Ukrainian and Byelorussian SSRs. In response to them, on December 4, 1939, the Politburo of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (BCP) was the first to respond positively. A day later, on December 5, 1939, the RKL of the USSR issued resolutions No. 2010-558ss (for Belarus) and 1001-558ss (for Ukraine) in which it was decided to clean the territories of these republics from settlement families threatening the social order. It was decided on 22 and 29 December 1939 that foresters and forest guards would be deported at the request of the RKL of the Ukrainian SRS and the Belarusian SRS. Four more resolutions were passed within a few weeks. December 21, the Politburo of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (b)

On the basis of the first of the resolutions, around December 9, 1939, L. Beria sent instructions to the regional NKVD boards of the Belarusian SRS and the Ukrainian SRS, obliging them to conduct, by January 5, 1940, lists of families of settlers and foresters subject to resettlement. Together with the instructions, guidelines for the NKVD were sent from the areas where the deportees were to be deployed in the future. NKVD negotiations were also started on the method of use and the amount of labor that individual Soviet commissariats and trusts of the forestry and mining industry would receive from the NKVD, as well as the sums that, due to the use of the quota, would flow into the NKVD accounts. On December 24, 1939, L. Beria sent a letter to Vyacheslav Molotov with a draft of executive acts prepared by the NKVD regarding future resettlements.

J. Stalin supervised the entire operation from the beginning. In the directives of December 19 and 25, 1939, he gave L. Beria detailed instructions on the course of the operation. This is clearly visible in the orders prepared by Beria on December 19 and 25. Based on them, on December 25, the head of the Belarusian NKVD, L. Canawa, sent out to his subordinate units guidelines for immediate preparation (according to the diagrams) of lists of settlers and their family members and sending them to the headquarters no later than January 5, 1940. According to Beria’s instruction of December 9, the censuses had to be carried out under the pretext of registering economic objects. Canawa’s order also specified the assumptions of the future deportation action. On each operating section (covering approx. 250-300 families) operating trios had to be organized, which was to be headed by the head of the regional branch of the NKVD. After approval (January 7, 1940), they were to prepare operational plans approved by the district trio and wait for orders.

On December 29, 1939, the RKL USSR, by Resolution No. 2122-617, approved the three most important documents. These were: “Instruction of the People’s Commissariat of Internal Affairs of the USSR on the order of resettlement of Polish settlers from the western districts of the USSR and BSRS”, “Regulations of special settlements and rules of employment of settlers displaced from the western districts of the USSR and BSRS” and “States of district and post-district NKVD Headquarters in settlements with of a special nature.” The instruction was signed by the people’s commissar of internal affairs, L. Beria, and confirmed by the head of the Department of Labor Settlements of the GULAG (Main Directorate of Reformation Camps and Labor Colonies) of the NKVD of the USSR, Lieutenant of State Security Mikhail V. Konradov. It contained guidelines necessary to undertake a mass deportation action of the Polish population. It stated, inter alia, that: “[…] Special displaced persons-settlers are directed to fell the Narkomles forest in the Kirov, Perm, Vologda, Arkhangelsk, Ivanovo, Yaroslavl, Novosibirsk, Sverdlovsk and Omsk oblasts, Krasnoyarsk and Altai Krai and the Komi ASSR [Komi Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic] and are deployed in works in individual settlements from 100 to 500 families in each. […]”. Within a maximum period of five weeks, the People’s Commissariat of Forest Industry of the USSR and the People’s Commissariat of Internal Affairs (NKVD) were to determine the places where the displaced persons would be placed, and the ministries of health, trade and communication would ensure their transportation (within the time limit set by the NKVD of the USSR), the necessary care and food for the journey . Expenses for this purpose were estimated at about 31.5 million rubles.

On December 30, 1939, the Chairman of the RKL Komi ASSR, Sergei D. Turyshev, received an excerpt from resolution 2122-617ss, in which it was mentioned that this republic would be the place of residence of the deported population. The letter recommended that the places of settlement, living quarters and transport necessary to transport the special displaced persons along with their belongings be prepared immediately. Taking advantage of this ordinance, the authorities of the republic sent special letters on January 4, 1940 to the chairmen of district councils, in which they announced that: “In the coming days, refugees and settlers from the Murashi station from Poland will be brought to your region in the number of […] families, 4 people in each family. This was followed by recommendations to prepare the regions to receive them. The execution date was set for January 8, 1940. January 5 Chairman of RKL Komi ASSR SD Turyszew received instructions from the RKL USSR on the acceptance and deployment of the special displaced persons. On the same day, the people’s commissar of internal affairs of the Komi ASSR, Mikhail I. Zhuravlev, informed SD Turyszew about the planned date of arrival of the first transports to the Murashi station. It was supposed to be January 29 or 30, 1940. This would mean that the first deportation was planned for mid-January 1940. Why were the deadlines not met? Most likely because of the Soviet-Finnish war. At that time, a major offensive was being prepared and most of the railway transport was involved in bringing troops, equipment and ammunition (among others from the Far East). Turyszew about the planned date of arrival of the first transports to the Murashi station. It was supposed to be January 29 or 30, 1940. This would mean that the first deportation was planned for mid-January 1940. Why were the deadlines not met? Most likely because of the Soviet-Finnish war. At that time, a major offensive was being prepared and most of the railway transport was involved in bringing troops, equipment and ammunition (among others from the Far East). Turyszew about the planned date of arrival of the first transports to the Murashi station. It was supposed to be January 29 or 30, 1940. This would mean that the first deportation was planned for mid-January 1940. Why were the deadlines not met? Most likely because of the Soviet-Finnish war. At that time, a major offensive was being prepared and most of the railway transport was involved in bringing troops, equipment and ammunition (among others from the Far East).

On January 9, 1940, L. Beria appointed a commission responsible for supervising the preparations and the course of the operation. It was composed of Vsevolod Merkulov, Vasily Chernyszow, Bachcho Kobulov and Sergei Milsztejn. It was here that the lists of persons subject to deportation, prepared by the district boards of the NKVD of the Ukrainian SSR and the Byelorussian SSR, were delivered. Another key document was the “Plan for loading, forming, transporting and reloading special NKVD transports”. It specifies the numbers of transports, loading and unloading stations, and possibly reloading stations, if deportees need to be transferred to wide-axle wagons, and the exact dates of echelon clearance.

The Convoy Troops of the NKVD were delegated to carry out the deportations. A typical convoy escorting a train with exiles consisted of 23 people. Convoy leader and 22 soldiers. In addition, each squad had two special deputies from the “operational staff”, i.e. NKVD functionaries responsible for political supervision of the exiles. The convoying unit was traveling in an attached passenger car. The warehouse manager collected the transport documentation at the place of loading necessary to settle accounts after delivering people to the place. This delivery and acceptance document (in three copies) together with the name list of those loaded onto the train and their personal files was used for efficient supervision of tens of thousands of exiles. One copy was given to the NKVD branch, which took over the deported at the unloading point, the second was sent to the Work Settlements Department of the GULAG NKVD – the headquarters supervising the work and life of all prisoners, the third was an attachment to the report on the performance of the assigned task by a given regiment or convoy battalion. Convoy troops from 13 divisions from Ukraine (convoy regiments and battalions from Kiev, Lviv, Odessa, Stanislaviv and Vinnytsia), from the 11th brigade from the Moscow region (convoy regiments and battalions from Moscow, Ivanov, Yaroslavl and Gorka) took part in the deportation operation. , from the 12th brigade from the North-West region (convoy regiment from Leningrad), from the 15th brigade from Belarus (convoy regiments and battalions from Minsk, Grodno, Brest, Smolensk and Baranowicze) and from the 19th brigade from Eastern Siberia (convoy battalion from Krasnoyarsk) . the third was an attachment to the report on the performance of the entrusted task by a given regiment or convoy battalion. Convoy troops from 13 divisions from Ukraine (convoy regiments and battalions from Kiev, Lviv, Odessa, Stanislaviv and Vinnytsia), from the 11th brigade from the Moscow region (convoy regiments and battalions from Moscow, Ivanov, Yaroslavl and Gorka) took part in the deportation operation. , from the 12th brigade from the North-West region (convoy regiment from Leningrad), from the 15th brigade from Belarus (convoy regiments and battalions from Minsk, Grodno, Brest, Smolensk and Baranowicze) and from the 19th brigade from Eastern Siberia (convoy battalion from Krasnoyarsk) . the third was an attachment to the report on the performance of the entrusted task by a given regiment or convoy battalion. Convoy troops from 13 divisions from Ukraine (convoy regiments and battalions from Kiev, Lviv, Odessa, Stanislaviv and Vinnytsia), from the 11th brigade from the Moscow region (convoy regiments and battalions from Moscow, Ivanov, Yaroslavl and Gorka) took part in the deportation operation. , from the 12th brigade from the North-West region (convoy regiment from Leningrad), from the 15th brigade from Belarus (convoy regiments and battalions from Minsk, Grodno, Brest, Smolensk and Baranowicze) and from the 19th brigade from Eastern Siberia (convoy battalion from Krasnoyarsk) .

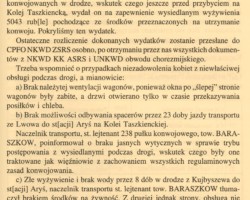

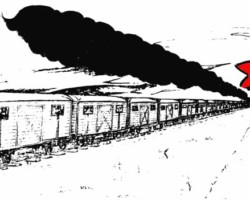

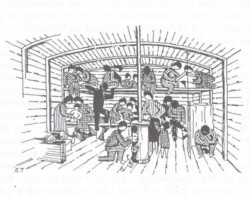

A typical train, supervised by the Convoy Troops of the NKVD, consisted of 55 wide-axle wagons of various tonnage, which, in accordance with the approved standards, were to accommodate 25 people. However, the number of loaded wagons could vary depending on the type of wagon, the number of substituted wagons in relation to the number of deportees and the whim of the loaders. Because wide tracks were not available everywhere until the first deportation began, there were cases of loading deportees onto wagons with a normal wheelbase, often taken over at stations in Poland, and then, at a designated staging point, detainees were reloaded to the depot where the actual transport was to take place. In this case, the number of exiles per one wagon could have changed again. The fact that the density could have been different can be seen in the reports of the NKVD Convoy Troops, where the numbers of people delivered to the place were given – transports had from 11,000 to 1,800 people. However, in extreme cases, we have information about escorting trains with up to 2,000 people, and in other cases, trains with 900 sent. If, on the basis of transport standards, we assume that the average transport should consist of 1,300 people, it is easy to guess that transports with more people, and there are many such in the lists of Convoy Forces, were most likely overloaded.

On January 10, 1940, Beria asked Stalin to transfer some of the displaced settlers to the People’s Commissariat of Non-ferrous Metals (Narodnyj Komissariat Tsvetnoj Metallurgii , hereinafter Narkomtsvetmiet) for gold and copper mining. The request was motivated by the fact that the families of foresters and forest guards were included in the contingent. On 14 January, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (b) and the RKL of the USSR issued an agreement to increase the number of displaced families of special displaced persons-settlers and to use them for mining and forestry works of the Narkomtsvetmiet. The resolution concluding preparations for deportation was the instruction for the heads of deportation depots on escorting special displaced persons-settlers. It was developed by the Main Board of Convoy Forces (Gławnoje Uprawlenije Konwojnych Wojsk ) of the NKVD of the USSR and approved on January 17, 1940 by the deputy people’s commissar of internal affairs W. Chernyszów.

In early February 1940, Vsevolod Merkulov and Ivan Serov arrived in Lviv to coordinate the operation in Ukraine. Already during the first inspections of the warehouses intended for deportation, gross irregularities were found in the adjustment of the wagons to the winter transport of people – there were no stoves, enough fuel and buckets, and broken and devastated bunks were found. Since there was no time for changes, the wagons were brought in as they had been prepared.

Two days before the start of the action, all designated military, NKVD and party forces were in place and awaiting orders. They received them on February 9, 1940. According to reports from Kiev and Minsk, 99,065 people (17,753 families) from Western Ukraine and 51,310 people (9,603 families) from Western Belarus were qualified for deportation. A total of 150,375 people.

Not all those deported in February had reached their destinations yet, when on March 2, 1940, both the RKL of the USSR and the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (b) decided to clear Western Belarus and Western Ukraine of three further categories of people:

- families of state and local government officials, judges, prosecutors, university professors, entrepreneurs and merchants, Ukrainian, Jewish and Belarusian nationalists, prison service and policemen, prisoners of war in Kozielsk, Starobielsk and Ostashkov, people arrested so far for political crimes, and all those who have escaped abroad, are hiding or are wanted;

- registered prostitutes with children;

- war refugees ( bieżeńców ) who came to the territories occupied by the USSR after September 17, 1939, who expressed their desire to go to the German occupation zone, but were not taken over by the Germans.

The same documents also contained arrangements for clearing the population of an 800-meter strip along the border with Germany. The idea of such a solution to the matter came from the First Secretary of the Ukrainian Communist Party, Nikita Khrushchev. He proposed to deport 22-25 thousand families to Kazakhstan. On March 2, 1940, the proposal found strong support in the person of L. Beria, which actually determined its positive consideration by the VKP(b).

Three days later, on March 5, 1949, the Politburo of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Poland (Beria) made a final decision on the fate of 14,700 Polish prisoners of war and over 7,000 other prisoners (3,425 in Ukraine and 3,880 in Belarus). Deportation of the families of the victims of the Katyn massacre (among those shot were 3,750 people from the territories seized by the USSR) was a way to cover the traces. Scattered on the endless steppes of Kazakhstan, the families could not claim their loved ones.

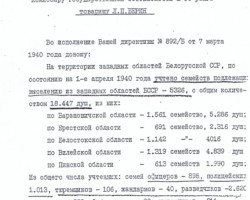

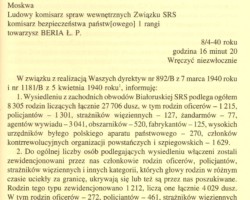

On March 7, 1940, L. Beria issued order No. 00308 on the formation of operational troikas responsible for the organization and conduct of the next deportation action and two documents specifying the tasks: No. 892/B – on starting the necessary preparations for deportation and 886/B – on the preparation of detailed Polish censuses officers in POW camps. During their preparation, it was necessary to determine the family status of prisoners of war sentenced to death and, if possible, the current address of residence. Wife and children as well as parents, brothers and sisters, if they lived in a common household, were considered family members. It was also ordered to prepare detailed data on the families residing in the German occupation zone, as there was a probability that they might reside in the areas occupied by the USSR.

Order No. 892/B specified the purpose, time and place of the action as well as the means to be used to carry it out. It was as detailed as the February deportation regulations. It covered both the process of preparations for the deportation and the course of operations of operational troikas in the homes of displaced families. According to it, all material goods of families: houses, outbuildings and flats were subject to confiscation, and they themselves had the right to take with them no more than 100 kg of items per person. It was five times less than during the February deportations. All emptied passage rooms were to become the property of the local authorities and subject to re-inhabitation. The Red Army soldiers and party activists assigned to work in the western districts of Ukraine and Belarus were to move in first. The February, economic aspect of the action repeated itself. The local authorities gained the exiles’ property and could dispose of it freely. Items that were not subject to confiscation could be handed over to neighbours. They were to sell them and send the proceeds to exiles. They only had 10 days to do so. Persons suspected of anti-Soviet activity were subject to immediate arrest. The preparations for deportation were to be reported by March 31 at the latest. those suspected of anti-Soviet activity were subject to immediate arrest. The preparations for deportation were to be reported by March 31 at the latest. those suspected of anti-Soviet activity were subject to immediate arrest. The preparations for deportation were to be reported by March 31 at the latest.

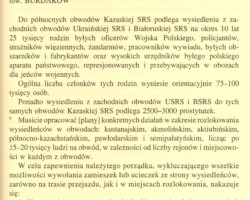

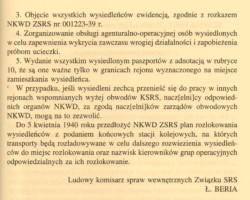

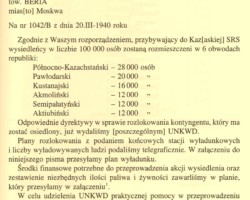

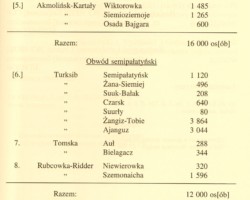

On March 20, 1940, L. Beria issued an order on preparations for the distribution of the deported population in the northern districts of Kazakhstan. In it, he wrote, among other things, that a quota of 25,000 families with a total of about 76-100,000 people would be subject to deportation for 10 years. 2-3 thousand prostitutes were also to be sent to Kazakhstan. The places of settlement were to be the following oblasts: Kostanay, Akmolin, Aktyubin, North Kazakhstan, Pavlodar and Semipalatinsk, according to the key of 15-20 thousand people per oblast. The regional authorities were obliged to develop a detailed distribution plan for the deportees by 5 April.

A day later, Beria turned to the People’s Commissar of Communications of the USSR ( Narodnyj Komissar Putej Soobshcheniya SSSR) Łazar M. Kaganowicz with a request to provide wagons necessary to “fulfill an urgent operational task” within 10 days. They were supposed to transport about eight thousand people from the NKVD prisons of the Ukrainian SSR. The same trains were then supposed to transport about three thousand prisoners from the western districts of the Ukrainian SSR to the central districts and about three thousand prisoners from the western districts of the Byelorussian SSR to Minsk. This document indirectly shows that most of those convicted under the regulation of March 5, 1940 were executed in Minsk or its vicinity. Since we have no data on the fate of prisoners shot from the so-called According to the “Belarusian list”, there is a high probability that Kurapaty is their final resting place.

On April 4, 1940, under the order 1173/B, L. Beria ordered to detain all former soldiers of the Polish army suspected of counter-revolutionary activities: corporals, platoon leaders, sergeants, senior sergeants, warrant officers and cadets.

On April 5, 1940, in letter No. 1180/B, he sent two projects for approval by the RKL USSR: “Resolution of the RKL USSR on the expulsion from the western districts of the USSR and BSRS of the families of people in prisoner-of-war camps and prisons and refugees from central Poland who were not accepted by the authorities German” and “Order of resettlement of persons included in the decision of the RKL USSR of March 2, 1940 No. 285127”.

At the same time, the deportation trains returned from the north to the newly designated stations to pick up the next contingent of exiles. On April 10, 1940, the RKL USSR, by Resolution No. 497-177ss, approved a slightly changed and adapted instruction on the mode of resettlement of “people specified in the Resolution of the RKL USSR No. 289-127ss of March 2, 1940”, and set the next its beginning on the morning of April 13, 1940. The main change was the exclusion of refugees from deportation due to the unexplained issue of their return to the German side. A limit of people per one wagon was also set – 30, and the daily norm of bread was lowered from 800 to 600 grams per person.

Families of people staying in POW camps and prisons, former officers of the Polish army, policemen, prison workers, gendarmes, scouts, former landowners, factory owners, employees of the administrative apparatus, participants of counter-revolutionary insurgent organizations and refugees from the territory of “former Poland” were qualified for resettlement. who expressed their desire to return to the German occupation zone, but were not accepted. The occupied territories also had to be cleared of prostitutes. Families of officers and policemen were excluded from the deportation. On the basis of the request of the 5th intelligence department of the USSR GUGB, they were left alive and transferred to the camp in Juchnów, and then in Gryazowiec. The order further specified the place where the exiles were to be sent and the means by which this should be done.

On April 10, 1940, decisions were made on both the April and June deportations. According to the documents, even before the RKL USSR formally decided to deport, the NKVD had already sent out all the necessary orders and conducted preparations. L. Beria was informed about them by the head of the Belarusian NKVD, L. Canawa.

The group that was the last to go to exile in 1940 were refugees from central and western Poland, in the terminology of the NKVD referred to as runners. Preparations for their deportation lasted from November 1939, when a resolution of the Politburo of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (BKP(b)) signed by Stalin and a resolution of the RKL USSR for 1855-486ss established a special government commission headed by Beria, which was to solve all problems arising from their presence on occupied territories. The irony of fate was that they were the first to be resettled deep into the Ukrainian SRS and Belarusian SRS already in October 1939, and eight months later they closed this most tragic period for Poles. For local authorities, they were a problem that needed to be dealt with as soon as possible. Fortunately for the refugees, the Soviet-German agreement concluded in December 1939 on the mutual exchange of people of German, Ukrainian and Belarusian descent temporarily stopped the deportation machine.

Due to delays in the work of the German-Soviet mixed commission during the approval by the RKL of the USSR of the decisions on the April deportation, this group was excluded from the planned action. Refugees were to be resettled after the population exchange (scheduled for early June 1940) was to be resettled on the same terms and based on the same ordinances that had already been passed. Before the decision was issued by the order of April 4, 1940, L. Beria approved and in subsequent letters supplemented the regulation regarding the preparation for deportation of this group as well.

The population exchange took place in the spring of 1940. The Soviet-German commissions were to enable refugees from both occupation zones to return to their places of residence. It turned out, however, that on the Soviet side there were twice as many people willing to return than the Germans assumed. In total, from April to June 1940, about 66,000 people crossed the Soviet-German border, out of over 164,000 seeking the right of return. Most of those rejected were refugees of Jewish nationality. And it was them who, at the turn of June and July 1940, were deported to the same areas where military settlers and foresters had previously been displaced. The same legal category was applied to them – displaced persons. It took place pursuant to the directive of the USSR NKVD No. 2372/B on the resettlement of the runners from the Ukrainian SRS and Byelorussian SRS sent by Beria to the republican NKVDs of the USSR and BSRS on June 10, 1940. June 29 was adopted as the start date of the operation.

The last deportation took place after a year of relative stabilization. On May 14, 1941, the Central Committee of the WKP(b) together with the RKL USSR adopted resolution no. On its basis, on May 21, 1941, L. Beria issued an order “on the resettlement of socially alien elements from the Baltic republics, Western Ukraine, Western Belarus and Moldova.” The action was preceded by extensive preparations carried out mainly by the NKGB (People’s Commissariat for State Security) and NKVD bodies responsible for revealing and drawing up lists of persons subject to repression. This time, the repressions hit the population from the intelligentsia, the refugees remaining in the cities, the families of railway workers,

In the case of this deportation, a new thing was the directives on disconnecting and arresting men – heads of families, who were sent to detention centers and then sent to labor camps in special transports. The detachment of the “head of the family” was decided by the local NKVD structures on the basis of documents in their possession about possible hostile activities of the detainee.

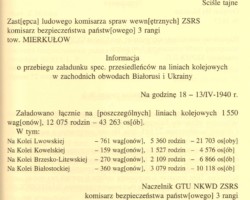

So far, researchers have not been able to determine all the transports in which over 330,000 citizens of the Second Polish Republic were taken to the East in four large deportations. It is known that in 1940 there were at least 208 warehouses. Approx. 100 as part of the February 1940 deportation, 51 as part of the April deportation and 57 as part of the June deportation. It is not known how many transports were organized during the deportation in the summer of 1941. Many were destroyed by the German air force after the outbreak of the German-Soviet war. Certainly, at least 35 trains left for the East from Western Belarus and Lithuania. Based on the number of people delivered to the places of settlement, it can be assumed that no less than 20 trains left the north-eastern lands of the Second Polish Republic in the summer of 1941. In these depots, apart from the deported, there were prisoners and “heads of families” separated during the deportations. In the case of Western Ukraine, the number of transports varies between 8-10. In total, in the period February 1940 – June 1941, there will be no less than 235 trains (echelons).

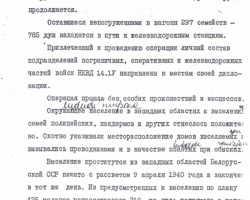

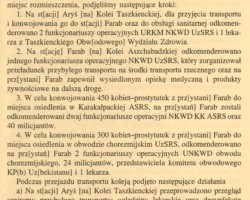

The course of mass Soviet resettlement actions in 1940-1941

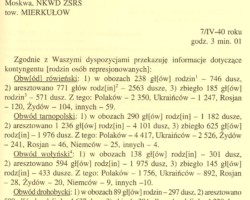

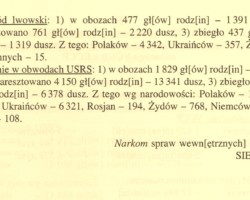

On February 10, 1940, in the early hours of the morning, the previously designated operational teams began to implement the provisions approved by the Council of People’s Commissars of the USSR on December 29, 1939. The operation officially ended the same day in the evening. A total of 89,062 people (17,206 families) were deported from “Western Ukraine”, and 50,732 people (9,584 families) from “Western Belarus”. During the action, 139,794 people (26,790 families) were loaded onto wagons and sent on their way (according to Soviet documents). The data of the Convoy Troops of the NKVD (People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs of the USSR) differ slightly and speak of 139,068 people, of which 50,683 were deported from “Western Belarus” and 88,385 from “Western Ukraine”. which means that 204 people died during the journey (0, 15% of deportees). These are not confirmed numbers, because in no case are we 100% sure that the estimates provided in the documents are complete.

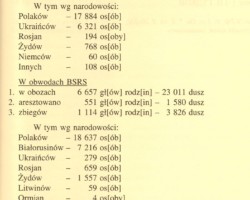

The February deportation covered mainly the Polish population. Military settlers (mostly former participants in the 1920 war) and forest service were sent there, as well as refugees from Russia after the civil war and the Bolshevik takeover of power. Numerous peasant families who received land as part of the parcelling of estates or purchased it for money and had nothing to do with the settlement policy of the Polish government were also treated as settlers. Among the deportees there was a small percentage of the Belarusian and Ukrainian population, mainly due to the fact that men – “heads of families” – served in forest management: forester, forest guard, etc. According to data from June 1941, Poles in the above-mentioned group accounted for 81.68%, Ukrainians 8.76%, Belarusians 8.08%, Germans 0.11%, others 1.37%.

The deported population was distributed in 115 special settlements, in Komi ASSR, in the northern districts of the Russian Federative SSR: Arkhangelsk, Chelyabinsk, Chkalov, Gorkiv, Irkutsk, Ivanovo, Yaroslavl, Kirov, Molotov, Novosibirsk, Omsk, Sverdlovsk and Vologda, in the Yakut and Bashkir ASSR and Krasnoyarsk and Altai Krai. The largest number of people were placed in the Komi ASSR (2,191 families), Vologda Oblast (1,586 families), Molotov Oblast (1,773 families), Sverdlovsk Oblast (2,809 families), Omsk Oblast (1,422 families), Arkhangelsk Oblast (8,084 families) and Irkutsk Oblast ( 2,114 families) and in Krasnoyarsk and Altai Krai (3,279 and 1,250 families, respectively). There were no less than 58,000 children under the age of 16, i.e. almost half of them. The displaced contingent was defined in the terminology of the NKVD as spiecpieriesielency-settlers.

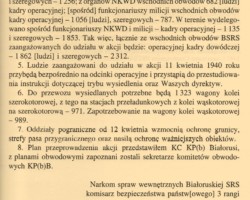

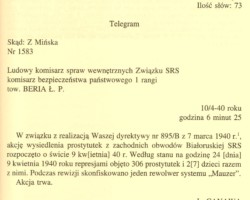

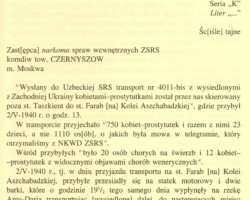

On April 9, 1940, prostitutes were deported to Kazakhstan. 307 of them were gathered from “Western Belarus” together with 35 children, from “Western Ukraine” at least 47 (no data on possible children).

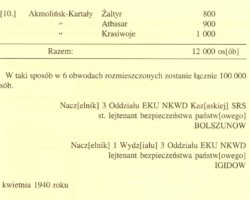

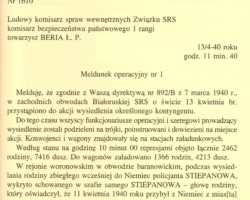

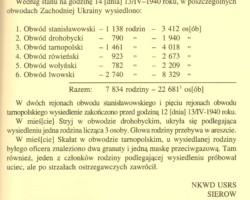

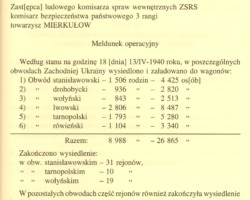

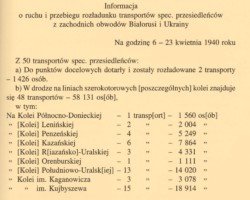

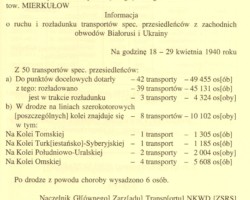

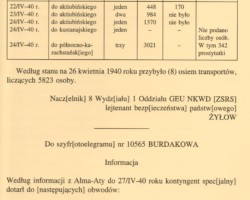

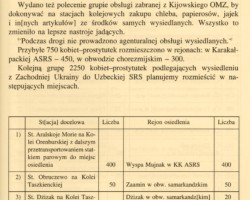

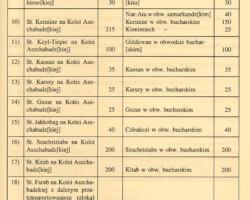

On the morning of April 13, 1940, 51 transports took 60,667 people to Kazakhstan, and according to other sources, 61,092 people. 29,699 people (8,639 families) were deported from “Western Belarus”, 26,777 people (8,055 families) were deported. The remaining group, about 34,000 people, were the inhabitants of “Western Ukraine”. On April 15 Lavrentiy F. Tsanava (real name Dzhanzgawa) – the head of the NKVD of the Belarusian SSR – reported that 28,112 people had been deported from Belarus, while the final report of Ivan Serov, People’s Commissar of Internal Affairs of the Ukrainian SSR, dated April 14, 31,332 were deported to Ukraine, making a total of 59,444 people. Among the deported, the percentage of Poles was approx. 69%, Belarusians approx. 13%, Ukrainians approx. 12%, Jews approx. 4%, Russians approx. 1.5%. Compared to 59.5 thous. deported, it gave 41.1 thousand. Poles, 7.7 thousand. Belarusians, 7.1 thousand. Ukrainians, 2.4 thousand. Jews, 0.9 thous. Russians. They were deployed in accordance with the directives of the NKVD in North Kazakhstan, in the Aktyubin, Akmolin, Kostanay, Petropavlov, Karaganda, Semipalatin, Pavlodar and North Kazakhstan oblasts. Several thousand people were also directed to the Chelyabinsk region. The percentage of women and children was exceptionally high in this case, due to the displacement of families of “enemies of the system”. It was even 65-70% of all transports. due to the displacement of families of “enemies of the system”, there was a percentage of women and children in this case. It was even 65-70% of all transports. due to the displacement of families of “enemies of the system”, there was a percentage of women and children in this case. It was even 65-70% of all transports.

The April deportees were referred to in the terminology of the NKVD as administratiwno-wysynnyje . The duration of their deportation was also formally set, which was to be 10 years. According to the reports of the Kazakh authorities, 35,528 deportees were sent to work in kolkhozes, 17,900 to work in sovkhozes, and a group of about 8,000 people to work in the construction of railways and roads, and to the gold mine (Majkain Zołoto in the Pavlodar region). Most of the deported came from cities and were not prepared for the hard, physical field work that they had to do, which is why the mortality rate in this group of people was particularly high. The exact national composition of those deported in administrative mode is still not possible to determine today. It is known, however, mainly on the basis of memoirs and diaries from that period, that the majority of the deportees were of Polish nationality. A significant percentage was also the Jewish population. Among the deported there were Ukrainian and Belarusian families.

Another deportation took place at the turn of June and July 1940. It began in the early morning of June 29. Due to difficulties in apprehending deportees and problems with transport, the operation extended to almost a week. It covered (as previously agreed) primarily refugees from central Poland rejected by the German resettlement commission. Families living in the border zone – up to 800 meters away – were also subject to deportation. In most cases, they were simply moved deeper into the oblasts to the farms left by those previously displaced. Sometimes the orders turned out to be different and these people, instead of a dozen or so kilometers, covered thousands of kilometers. In this case, the deportation to the north was mainly due to

Most of the deportees in this case were of Jewish, Belarusian and Ukrainian nationality. According to NKVD sources, Jews accounted for over 80% of the total deported contingent. According to NKVD data for the second quarter of 1941, among the 76,113 deportees, there were 84.56% Jews, 10.95% Poles, 2.26% Ukrainians, 0.24% Belarusians and 0.16% Germans. The final number of deportees, who in Soviet documents are referred to as spiecpieriesielency-bieżency, who are also referred to as “the contingent of people who are to go to Germany but not accepted by the German authorities”, amounted to 80,653 people. 22,879 were deported from “Western Belarus”, 57,774 from “Western Ukraine”. Data from the Convoy Troops of the NKVD say that 57 trains transported 76,246 people (52,617 from “Western Ukraine” and 23,629 from “Western Belarus”). The Soviet authorities failed to implement their plans to the end. As many as 102,683 people (83,207 family members and 19,476 single people) were originally intended to be resettled in “Western Ukraine”, and at least 23,057 people in “Western Belarus”.