Part Two – The USSR and Gulag

Hunger

It’s so true that a well-fed person cannot understand the starving one. I had been malnourished continuously for a long time, but the hunger which forces every cell to scream only started in Punishment Camp Number 6 in the fall of 1941. For the second time my body began to bloat as prelude to death by starvation. My hunger was so overwhelming that stones looked like loaves of bread, and I wanted to chew bark and leaves. I prepared myself for death.

But a few weeks after my friends had left, I was ordered on the kitchen night shift. Once more my life was saved by chance, or fate. A woman was caught stealing, and the supervisor complained that he only wanted honest Poles. There was only one Pole left–me. The cook saved the best for himself and his staff: thick servings scooped from the bottom of the kettle over which was poured fish grease. And we could eat as many baked potatoes as we could. I stuffed myself so much that I found it hard to scrub the floor. And yet my body screamed for protein and vitamins. We often gutted and prepared small greasy fish; by boiling them we extracted pure grease—which I drank with a bit of bread. It was heaven. During my several months in the kitchen, my swelling subsided, but the scabs on my legs would not fully heal. At least I was alive.

I worked in the kitchen from 7 at night to 8 in the morning when I’d collapse on my bunk. I’d start each shift by preparing meals with fish, cucumbers, potatoes, tomatoes, which was the regular prison food. For those prisoners who worked in the “office” or at other special duties there were perks. These were opportunists and traitors who profited at the expense of those who worked hard. On top of regular rations they received pasta and grain dishes as well as treats made from fruit. They ate well while others starved to death.

I stole food from the kitchen. Otherwise I would have perished. But I also smuggled fish and potatoes in the laundry or in my apron to help the starving–in particular two older women, both very religious, who were awaiting trial for refusing to work for a godless system. Such a refusal was considered sabotage by the Soviets, and execution faced them. In exchange for little scraps of food, they darned my clothes.

Camp Commander had been replaced shortly after we’d arrived, amid rumors that too many prisoners were dying and work-quotas were suffering. The NKVD assigned a more “humane” official. He increased food levels and even managed to get a boxcar of frozen chickens, geese and rabbits. But this was nothing in the long run. We were allotted three or four chickens for a pot that was to feed four hundred people toiling hard in freezing conditions. And that was the first kettle reserved for the hardest working! The second one had a few small fishes while the third contained rejects from the second.

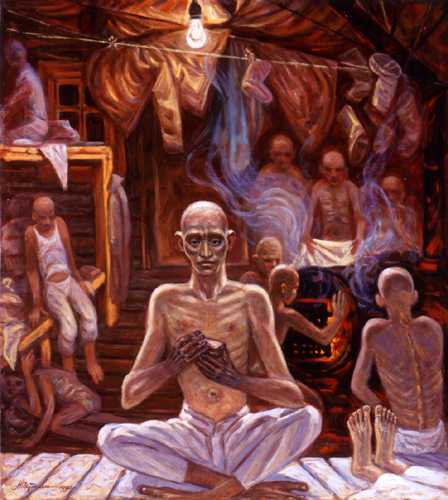

The Walking Dead

Cutting frozen and salty fish was hard work; my fingers ached and it was impossible to avoid cutting oneself. Part of my my job was to throw scales and intestines in the trash pit at the end of the camp. It was here that prisoners on their last legs, unable to work and not receiving rations, would come to feed on what was considered unfit for human consumption. Dr. Reczynski decreed that I should start throwing the remains into the latrine pits as the situation was “unsanitary.” This was done and the scavengers soon disappeared–most likely dead from starvation. A week later I came upon a pitiful sight at the latrine. A group of men looking like scarecrows was actually engaged in fishing the entrails from the human waste with sticks! They would place their catches on filthy rags–and even fight over them. Several of these poor souls drowned in the latrines and the others soon died off. That winter up to eight people were dying daily from hunger, freezing and overwork. Several times I visited the mortuary which was overflowing with stiff bodies stacked like cords of wood, waiting to be buried in the “Polish cemetery.” These corpses bore little resemblance to humans: limbs and faces swollen and covered in wounds, while backbones poked though collapsed stomachs. The evil Dr. Reczynski claimed that come spring the death toll would be even higher.

This prison was full of the worst–and the best of humanity. Murderers, rapists and assorted criminals, some of whom stepped into positions of guards and interrogators for the camp authorities. They took great pleasure in beating and tormenting other prisoners. Among the most noble was Wasyli Stepanowicz Powierynow, director of the kitchen. An actor by profession, he’d recite poetry, act out passages, and entertain us as we worked. Our small group of Poles and political prisoners formed a plan in case the prison was abandoned by the Soviets, leaving us at the mercy of the criminal element which outnumbered us. Their first act would be an attack on the food supplies, followed by a slaughter of the politicals. We set up areas near the morgue to hide food and make a stand. We didn’t know that in the event of German incursion, the NKVD would liquidate us, as they had done in previous situations.

Forestry

In January we were all given a clean bill of health–even those who were clearly dying. More workers were needed to meet production quotas for lumber. The kitchen staff was pronounced fit enough to go back to the forest as were others on “light” duty. Wasily Stepanowicz, the cook Mitka and myself, formed the core of the “kitchen-fire” brigade as we were referred to. I was a suczkozog whose job was to build and maintain fires to burn branches, and for warmth and cooking. We received new winter clothing: tielogreyki – pants made of quilted material, watneje czulki – cotton leggings, as well as hats with earmuffs, gloves and fresh lapcie.

Reveille was at four in the morning with the usual counting, grumbling and even fighting. A list would be read aloud of those sentenced to death for refusing to work. At 5 a.m. we’d be handed tools by guards who warned against trying to escape, and in single-file, or in pairs, we’d make our way through huge snowdrifts patrolled by guards on skis. If it was extremely cold we’d be given black Vaseline to smear on our faces for protection. According to regulations, temperatures of -40C were considered too cold for work–but only once were we held back. That day I lay on my bunk bundled up and waiting, while a neighbor told me stories of the diedmot, bands of children, that roamed the countryside as bandits and were even bold enough to attack trains.

Each brigade had its section and quota of lumber. This involved felling the trees, cleaning them of bark and branches, cutting it into timber, and stacking the product for removal on horse-drawn wagons or sledges. I had to start and maintain up to four fires at one time. Even in the coldest weather a few embers would remain of the previous day’s fire which made my job easier, and warmed everybody until the sun came up. Lunch was the most enjoyable time. Every day a soldier would arrive on skis with a shipment of mahorka [tobacco substitute made from plants] which would be given only to those who fulfilled 100% of production. Some mahorka would be shaken into your little bag called a kiset–and with a bit twisted paper you’d soon have a cigarette. We’d then sit around the fire and exchange stories. One fascinating conversationalist was a Doctor of Philosophy from Hungary who had been a compatriot of Bela Kun, and had been part of the bloody communist takeover of Hungary in 1919. He and the whole leadership had been invited to Russia by Stalin where they were entertained and praised by Soviet propaganda–only to be then either executed or sent into the camps. Poetic justice!

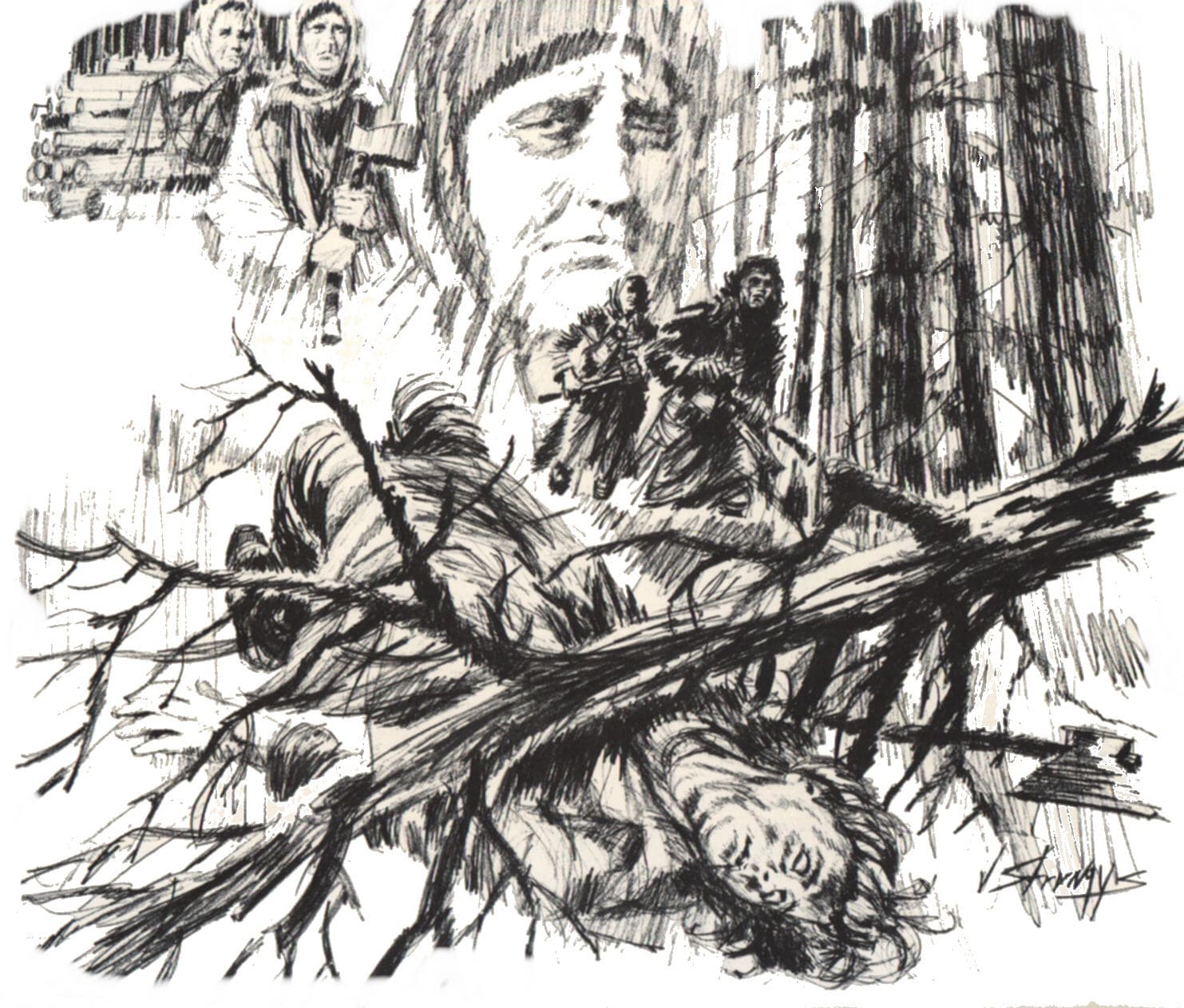

Mutilation and Murder

There were strange and tragic occurrences in the forest. A mechanic from a labour-camp in the north, serving time for insubordination, refused to do any more work. He lay down beside one of my fires and fell asleep. Suddenly a horrible scream echoed through the forest. I beheld a human torch thrashing about wildly–it was our mechanic. Powierynow rolled the man across the snow and ripped off his flaming clothing…but the man suffered horrible burns. The Kawecze showed up and wrote down the details. The tielogrieka, gloves and other state property had been damaged: a clear case of sabotage! Naked and burned, the man was taken back to camp at the end of the day, and thrown into an isolation cell to await his trail. We could hear him screaming for days before he died.

I was witness to cases of suicide and mutilation. Those who suffered accidents or frostbite could be released from work for a time…and some exposed themselves deliberately (I recall seeing many victims with blackened appendages or with toes and fingers missing). Work-brigades even caused accidents in order to claim the food of the victim. I once witnessed two men staging an “accident” in the forest. The “victim” placed his hand on the trunk of a selected tree, and awaited a cut tree to fall his way–a horrible scream and the deed was done! The guards arrived, but the victim and his partner were charged with sabotage. It was very difficult to fool the NKVD. Amazingly it was much easier to cheat in work quotas. This process called tufta involved double-counting and rotating production for a second time, as well as bribing the counters and guards. The cutting of trees was risky. One of my brigade had both her legs broken when she couldn’t get out of the way, while another

woman was struck in the head. Someone began screaming “Mazgi!” [brains] as it appeared that the woman’s brain had been exposed. But the branch merely scalped her, and the skin was sewn back. It was this accident that shook me from thoughts of suicide which had been haunting me through the days of February. I’d been circling trees planning an end that would be quick–but I’d always run away. Years later this memory dissuaded me from thoughts of suicide in the London subway.

I witnessed the degeneration of the giant Miedwiediew, strong as a bear, and the leading worker in camp. But a few short months of the Gulag transformed him into a dochadiaga [beggar] scrounging for scraps. He simply could not survive on food that barely sustained people half his size.

I worked in the kitchen from 7 at night to 8 in the morning when I’d collapse on my bunk. I’d start each shift by preparing meals with fish, cucumbers, potatoes, tomatoes, which was the regular prison food. For those prisoners who worked in the “office” or at other special duties there were perks. These were opportunists and traitors who profited at the expense of those who worked hard. On top of regular rations they received pasta and grain dishes as well as treats made from fruit. They ate well while others starved to death.

I stole food from the kitchen. Otherwise I would have perished. But I also smuggled fish and potatoes in the laundry or in my apron to help the starving–in particular two older women, both very religious, who were awaiting trial for refusing to work for a godless system. Such a refusal was considered sabotage by the Soviets, and execution faced them. In exchange for little scraps of food, they darned my clothes.

Camp Commander had been replaced shortly after we’d arrived, amid rumors that too many prisoners were dying and work-quotas were suffering. The NKVD assigned a more “humane” official. He increased food levels and even managed to get a boxcar of frozen chickens, geese and rabbits. But this was nothing in the long run. We were allotted three or four chickens for a pot that was to feed four hundred people toiling hard in freezing conditions. And that was the first kettle reserved for the hardest working! The second one had a few small fishes while the third contained rejects from the second.

This prison was full of the worst–and the best of humanity. Murderers, rapists and assorted criminals, some of whom stepped into positions of guards and interrogators for the camp authorities. They took great pleasure in beating and tormenting other prisoners. Among the most noble was Wasyli Stepanowicz Powierynow, director of the kitchen. An actor by profession, he’d recite poetry, act out passages, and entertain us as we worked. Our small group of Poles and political prisoners formed a plan in case the prison was abandoned by the Soviets, leaving us at the mercy of the criminal element which outnumbered us. Their first act would be an attack on the food supplies, followed by a slaughter of the politicals. We set up areas near the morgue to hide food and make a stand. We didn’t know that in the event of German incursion, the NKVD would liquidate us, as they had done in previous situations.

Forestry

In January we were all given a clean bill of health–even those who were clearly dying. More workers were needed to meet production quotas for lumber. The kitchen staff was pronounced fit enough to go back to the forest as were others on “light” duty. Wasily Stepanowicz, the cook Mitka and myself, formed the core of the “kitchen-fire” brigade as we were referred to. I was a suczkozog whose job was to build and maintain fires to burn branches, and for warmth and cooking. We received new winter clothing: tielogreyki – pants made of quilted material, watneje czulki – cotton leggings, as well as hats with earmuffs, gloves and fresh lapcie.

Reveille was at four in the morning with the usual counting, grumbling and even fighting. A list would be read aloud of those sentenced to death for refusing to work. At 5 a.m. we’d be handed tools by guards who warned against trying to escape, and in single-file, or in pairs, we’d make our way through huge snowdrifts patrolled by guards on skis. If it was extremely cold we’d be given black Vaseline to smear on our faces for protection. According to regulations, temperatures of -40C were considered too cold for work–but only once were we held back. That day I lay on my bunk bundled up and waiting, while a neighbor told me stories of the diedmot, bands of children, that roamed the countryside as bandits and were even bold enough to attack trains.

Each brigade had its section and quota of lumber. This involved felling the trees, cleaning them of bark and branches, cutting it into timber, and stacking the product for removal on horse-drawn wagons or sledges. I had to start and maintain up to four fires at one time. Even in the coldest weather a few embers would remain of the previous day’s fire which made my job easier, and warmed everybody until the sun came up. Lunch was the most enjoyable time. Every day a soldier would arrive on skis with a shipment of mahorka [tobacco substitute made from plants] which would be given only to those who fulfilled 100% of production. Some mahorka would be shaken into your little bag called a kiset–and with a bit twisted paper you’d soon have a cigarette. We’d then sit around the fire and exchange stories. One fascinating conversationalist was a Doctor of Philosophy from Hungary who had been a compatriot of Bela Kun, and had been part of the bloody communist takeover of Hungary in 1919. He and the whole leadership had been invited to Russia by Stalin where they were entertained and praised by Soviet propaganda–only to be then either executed or sent into the camps. Poetic justice!

Head-counts saw strange things. One morning we had been lined up shoulder-to-shoulder for quite a long time in a snowstorm as things were not adding up. The guard got to a prisoner who would not respond, and in anger he punched him. The prisoner toppled over stiff as a board. He was dead and had been frozen in place and held up by other prisoners. The guard swore in amazement–and the camp erupted in hysterical laughter. What a joke had been played on that guard!

A murder took place next to me. Standing outside the gate waiting for our tools, I had been talking to Mitka the cook, and had turned away. A thudding noise caused me turn back. There lying in the snow was Mitka with an axe embedded in his head! Blood was spurting everywhere. A prisoner had taken revenge on Mitka who was merciless in beating prisoners caught stealing food. Mitka went to the morgue and his murderer to the jail.

Amazing News – Moses’ Prophecy

The last days of February were unusually warm. We were marching back after a day’s work where my brigade had exceeded the quota. I was happy I’d receive portions from the first kettle. And tomorrow was a rare “free” day where inspection would take place, and we could sleep longer, do laundry or visit each other. I then recalled the prophecy of Moses and realized that it was the end of February, and I was still in prison. So much for her prediction of being released that month.

Settled in my bunk, I was roused by a soft voice: “Jana, you’re going to your freedom.” It was the Russian secretary from the office, the same one with whom I had pleaded about not being released. Was I dreaming? Was this a cruel joke?

But the booming voice of Zylin, now demoted to a senior guard, confirmed that it wasn’t a lie: “Jana, go to Ola and tell her you’re going to freedom. Turn in your prison clothes and report to the baths.”

Christopher Jacek Gladun was born in 1951 and grew up in Canada to where his family emigrated from England as displaced persons. Sadly, Chris died in Toronto in March 2003. He held a diploma in Journalism from the Niagara College and a BA in Polish Language & Literature from the University of Toronto. Chris also acted as interviewer and researcher for the documentary film “Rescued From Death in Siberia”.

This content is now maintained by the Kresy-Siberia Group, which Chris was a charter member of and which is taking his website and his research work forward.