Part Two – The USSR and Gulag

Kiev Prison

That evening our group was thrown into a dingy basement cell. For Granny the return to Kiev was terrifying. Eight years previously she had smuggled her four children from the forced famine here–and now she was being taken back to Soviet hell. Granny began praying and then became hysterical, saying we’d all be shot the next day.

In the morning we were quarantined in an old wing of the building–typhus had occurred in the transports. On the wall someone had written: “Who was here, will not forget. And who has not been here, beware!”

Daily a nurse would come to check on us, and it was obvious this woman, raised in the USSR, was both repulsed and fascinated by the Polish “ladies.” We began a hilarious game of acting like great ladies of the court, tying ribbons in our hair and adorning ourselves with coloured rags. This charade soon induced other staff to gather and observe us praying, singing and carrying on.

There were some twenty of us, mostly political prisoners, with a few ordinary criminals. The youngest of those was a frightened 13-year-old Hucul from the East Carpathians, who in broken Polish told us that she was serving time for stealing a kerchief. We “adopted” this girl and doted on her, and when she was removed, it was like losing our own child. There was also a Russian peasant sentenced for stealing heating oil. She explained to the court that she needed it to keep her children from freezing while her husband was in the army. Soviet justice was moved and also sentenced her children to a children’s camp away from their mother.

Being quarantined gave us the freedom to pursue various activities. We sewed clothes out of scraps and knitted hats with the aid of broom straws. We devised contests and revived games from childhood. Those who had musical or acting skills would put on shows–like the Professor of Music, who gave concerts with her comb.

After a month we were herded into a huge hall for a major transport with hundreds of women from the entire prison. I was reunited with friends from Dubno prison, among them Marzenka Piatkowska and Dzunia, and we caught up on news. Our means of travel was one from Czarist times: the Stolypin wagon. Armored, windowless and divided into tiny cells, it was like being entombed in a can. We were given bread and fish, but no water: the guards were thus able to avoid the bother of washroom breaks. But after just a few hours our thirst was overpowering, and the trip was hundreds of kilometers. Dzunia fainted twice and one woman died in this transport. Her death was ruled an accident. That is how the Soviet system eliminated “class enemies” without actually executing someone. Such deaths would be listed as an accident in transit, a mishap at work, sickness, or shot will trying to escape–multiplied into the millions. Soviet paperwork was a masterpiece of euphemisms.

Kharkov – Transit Prison Nr.6

They unloaded us some distance beyond the station–a usual procedure. After undergoing repeated head counts, guards with dogs and bayonets hurried us up into columns. Just then an elderly woman collapsed on the rail tracks. A locomotive was backing up and several of us jumped to her aid. But a guard let loose several dogs which began tearing at the woman

too weak to move–and then he thrust viciously at her with his bayonet. The women let out a horrid scream, but it was her pack that was impaled. The guard flung it at us as we rolled the poor woman away.

We spent the first night in the corridor of Kharkov Prison which we were warned was harsh. We peeked inside one of the cells, and beheld a Dantesque scene: a thigh here, a buttock there–naked bodies shimmering with black grease! This was the cell for women suffering from scabies, and the grease was a balm–but I was sure I was witnessing one of the lower the circles of purgatory.

We were shuffled from cell to cell, each more crowded, even as transport after transport arrived. Most nights the corridors echoed to the coughs and snoring of male prisoners who would then spend days sitting in the courtyard. In this prison I met Poles, Russians, Ukrainians, Lithuanians, Latvians, Jews, Rumanians, Estonians, Byelorussians and others. We were mostly political prisoners. Some had already spent time in other prisons and were in transit to a labour camp to serve their sentence; others were awaiting their cases or still undergoing interrogations. There were also common criminals who were suspicious of the political prisoners except for what they could steal. Our huge cell was crammed with several hundred women and it was usually bedlam; sleeping was done in shifts.

Name Day Celebrations

I visited four cells and the infirmary where I met many interesting women. Some of them celebrated my second name day in prison. Each woman contributed a thread from her clothing to my present, a tie embroidered with “May 16 , 1941, Kharkov.” I still have that tie. Just at the high point of singing and celebrating, an NKVD officer rushed in with his guards.

“Off to the isolator!”he screamed and grabbed an elderly Polish embassy worker jailed for being posted to Berlin. For her this was a death sentence.

But an actress from Lwow jumped up and delivered a stirring confession that she was responsible for this “cabaret.” I also insisted it was my fault as it was my name day—and quickly others joined in, all demanding to be sent to the isolator. The officer stared incredulously at this mob of martyrs. “The devil take you all!” he snorted and slammed the door.

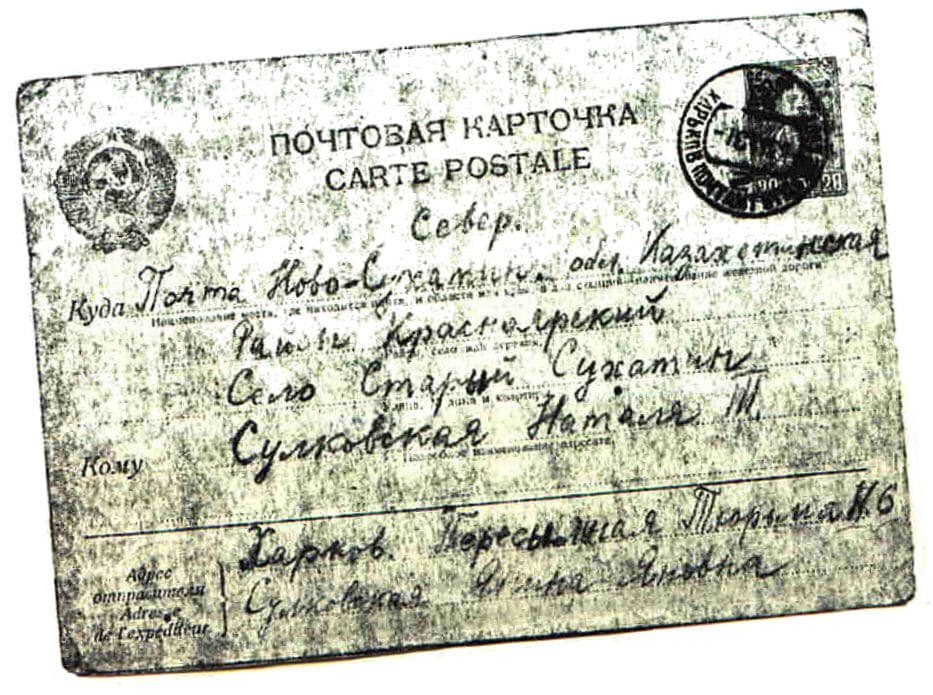

Luckily through Dzunia’s parents I managed to get my mother’s address in Siberian exile, and I wrote a tearful postcard in Russian (with the help of Marzenka), hoping it would reach my mother, sister and brother. And it did. Just days after writing it, we were on the move once more.

Starobielsk

In a June heat wave, a trainload of prisoners set off for Starobielsk some 150 kilometers south of Kharkov. I was frantic that Dzunia was forced to remain behind. Would she catch up to me and Marzenka in the next shipment? The trip had the usual deaths from dehydration and asphyxiation in the cattle cars; bodies were thrown out at stops along the way.

Starobielsk Prison was a converted Russian Orthodox monastery. Some 4,000 Polish Officers had been held here as POWs in 1940–but we did not know that almost all of them had been murdered by the Soviets, as were those in other camps. Among them were the husbands, sons and brothers of the women who now slept in the same bunks and hoped to be reunited with them.

Children Prisoners

Near the main cupola there was a building which housed Polish girls aged 12 to 16. We were perplexed by the sight of some of them carrying somebody wrapped in a blanket to the bath house. Was one of them a cripple or sick? We learned there were several Orthodox nuns in the same building who refused to participate in the communal baths where nudity prevailed. The prison authorities insisted they must take the baths. It was a dilemma which our Polish girls cleverly solved, and which left the nuns with a clean conscience, and a clean body, and satisfied prison policy. At bath time the girls would “kidnap” a nun and transport her in blanket to the bathhouse where they would disrobe and wash her–with their eyes closed.

Polish boys also were kept in a separate building. They were put to work carrying kettles of boiling soup or “coffee” from the kitchen. I cried every time I saw their determined smiles as they struggled with huge loads teetering on legs malformed by disease and rickets. There were accidents and many boys simply were never seen again. In some cases they had mothers who kept vigils at a prison window to get a glimpse of a beloved son. At any time they could be shipped out separately by the Soviets.

My father was actually here at the time I arrived, but shortly he was put on the transports further into the USSR, and we didn’t learn of each other’s presence. Pius Zaleski was also a prisoner here, and he not only met my father, but gave him a pair of his own pants. Pius was suffering from malnutrition and some Polish doctors tried to take care of him, but his kidneys failed. Before he died he requested that his school in Warsaw be told of his death. Pius’s body was dumped into a mass grave.

At the back of the of the prison yard a ramshackle building housed the terminal cases. Usually men, near death’s-door and often insane. We observed them with a mixture of pity and horror: skeletal figures in rags, shuffling aimlessly, mumbling or erupting in horrid laughter. One figure rocked back and forth whimpering in a monotone, oblivious to the world. He might have been a banker, a scientist, a famous writer–but he was far beyond that now. It seemed to me that the women were much better at survival than men. Somehow we were able to form a community that in spite of hunger and suffering, was able to give strength to its members. Men tended to collapse into their misery while women sought each other for support.

Inexplicably Starobielsk prison was being evacuated. It was the end of June and the process took several days. There were rumors that the Soviets were making room for German prisoners though no one thought that the Germans and their Soviet allies were about to fight. Group after group was led to waiting trains. Sitting near the church being endlessly counted, we could follow the progress of the guards searching for prisoners by their banging on the walls of the huge cupola. A horrid beating awaited anyone who hid in the rafters or belfry.

Christopher Jacek Gladun was born in 1951 and grew up in Canada to where his family emigrated from England as displaced persons. Sadly, Chris died in Toronto in March 2003. He held a diploma in Journalism from the Niagara College and a BA in Polish Language & Literature from the University of Toronto. Chris also acted as interviewer and researcher for the documentary film “Rescued From Death in Siberia”.

This content is now maintained by the Kresy-Siberia Group, which Chris was a charter member of and which is taking his website and his research work forward.