Part One – Poland

Janina Sulkowska, 1934

Janka and Wanda oblivious to the horrors that would soon engulf them.

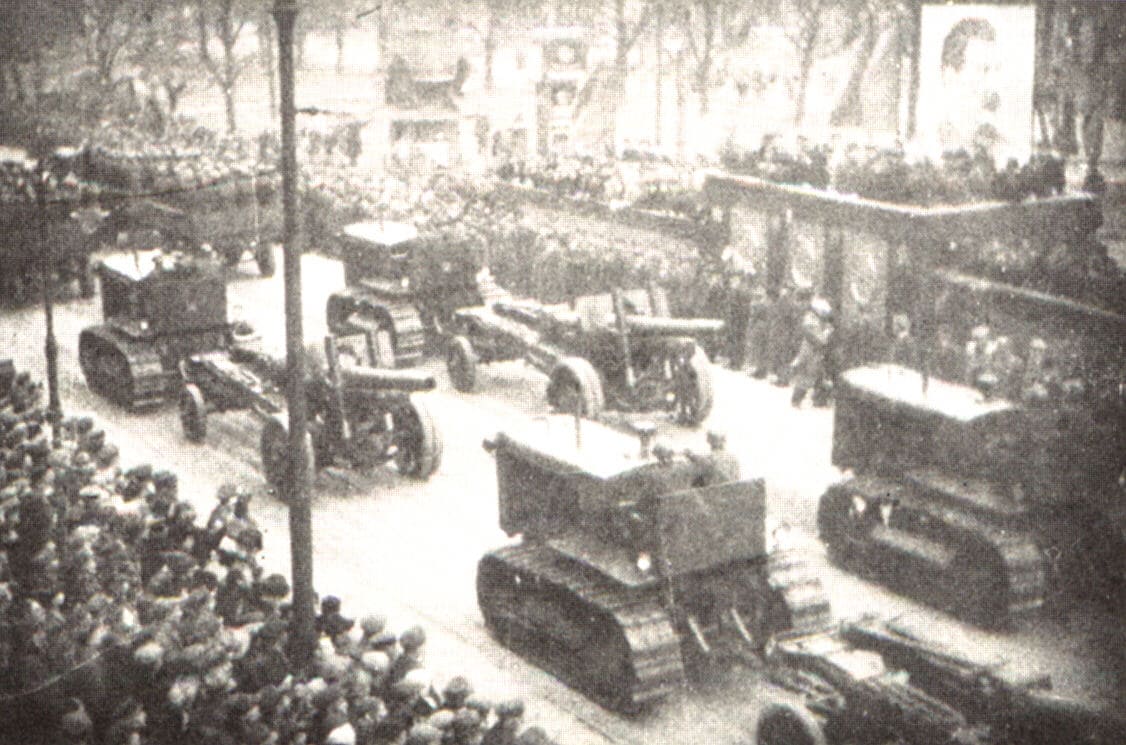

Red Army Parade in Lwow

Red Army Solider Killing a Polish Officer. Such posters went up even as the Polish Army was fighting the Nazis and the Soviets. In Krzemieniec local Ukrainians and Jews betrayed Polish soldiers and put up notices urging the murder of Poles. Some acted on it....

The Red Army Invades

At 5 a.m. on September 17, 1939, our telephone rang. It was the third week of war and it had been ringing day and night with urgent messages for my father Jan in his official capacity–often the only contact I had with him was running errands for him across the city. Before I could throw on a housecoat, he had already run from the bedroom, not waking his wife Natalia, and picked it up. He was quite used to the routine by now.

On the other end was Starost [chief official of the county] Zaufal, and a family friend, with some very important news.

“Hello…I’m listening…Yes…When?…Where?…I see…I see–” my father’s voice trailed off chocked with emotion and chronic bronchitis.

Jan Sulkowski slowly hung up. I watched him as a silhouette swaying against our veranda doors–his gold bracelet glinting in the early dawn as he cradled his head in a pair of graceful but trembling hands. He said nothing as he tried to compose himself..

Finally he whispered: “The Soviet Army has crossed the border…it’s all over…it’s the end.”

“Maybe they’re coming to help us against the Germans!” I spoke up trying to bolster our spirits. He just put his arm around me and shook his head. We both realized that it was all over for Poland. But what lay in store for the Sulkowski Family?

That day the sound of artillery echoed from the hills east of Krzemieniec as our lightly-armed Frontier Defense Corps opposed the Red Army which was pouring across the border with masses of soldiers and tanks. Locked in mortal combat with the Nazis, we did not anticipate an attack from that direction and our shock was considerable. Confusion reigned as to the intent of the Soviet Union, but Poland was not privy to the secret protocals of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact which would see us divided between our two age-old enemies: Germany and Russia.

A horror unimaginable by Poles was closing in from both sides, and it was the last straw for some. That day a single revolver shot in the Bona Hotel announced the suicide of Senator Siedlicki who also was Head of the Theosophical Society for Poland. Meanwhile, our British and French “allies” confined themselves to dropping leaflets and issuing threats as casualties in Warsaw surpassed 40,000.

Later that morning my father dispatched a county car to pick up my sister Wanda and brother Czeslaw from a vaction spot in the country with friends where they’d been dispatched following the German air attack on Krzemieniec a few days earlier. Home was now the only place for the Sulkowski Family to face a dark future–one which would split our family apart forever.

Greta Garbos and Jewish Collaborators

The next morning a nauseating smell of crude burnt fuel and a rumble of tanks and tractors announced the arrival of the Red Army into our beautiful town. I ventured into the streets to see what it was all about.

My introduction to the Red Army were rag-tag soldiers marching out of step and machinery that constantly broke down leaving a mess of mud and oil. Even the NKVD officers wore canvass boots and tattered greatcoats. Though they were well-armed, the Red Army didn’t bring supplies with them, and an occasional soldier would break from the ranks to make a quick purchase. Their eyes bulged at the amount and quality of goods in the stores even as they insisted that they had “plenty of everything in the USSR–including Greta Garbos!” During their entrance one of the Soviet soldiers slipped from a vehicle and impaled himself on one of their long four-cornered bayonets–the Soviets gave him a great funeral. What a contrast to our 12th Ulan Regiment which paraded on national holidays in beautiful uniforms and magnificent steeds.

The Poles watched the Soviet invaders with a mixture of revulsion and fear. Not a few of us cried. My brother became so distraught that shortly after, his hair began to come out in clumps while my little sister could only ask: “How could they do this?” But as disconcerting was the emergence of a local Jewish militia which was friendly to the Red Army and had made its appearance even before the enemy had marched in. Armed and organized, its first task was to arrest the students and Boy Scouts who had been posted as guards with old carbines in some cases taller than them. The Jews roughed up the shocked youngsters who had considered their captors as friends and classmates, before turning them over to the Soviets from whom they had prior directions. What was the fate of these young Poles? In many cases torture and death. This Jewish militia would help carry out the Soviet’s dirty work during their occupation. My family and others would fall victim to them.

In town, many Jews and Ukrainians were cheering and ingratiating themselves with the Soviets. I recognized neighbours and acquaintances among those who were jostling and searching Poles or eyeing their property for future theft. Jewish men offered gifts to the Russians while their wives and daughters kissed their tanks. Among this rabble were ordinary criminals released from our jail by the NKVD to create mayhem–one of them, a murderer, appeared at our door demanding my father pay him “backwages!” They were all emboldened by posters that had suddenly appeared urging Ukrainians, Jews, peasants and others to attack Poles and Polish soldiers with axes and scythes. And the Soviet officers indicated they would not stand in the way of such slaughter which was already turning the countryside red with the blood of a Polish minority outnumbered by Ukrainians and Jews. The county of Krzemieniec was 42% Ukrainian, 35% Jewish and 15% Polish–and an influx of Jewish refugees, many of them pro-Soviet, would tip the scales even further against us.

On that day I had my first encounter with a swaggering group of traitors attired in leather jackets, red armbands or sashes, pistols, and hatred in their eyes. I beheld classmates among them, including girlfriends. These mostly young Jews, often well-educated and from rich or religious families, now addressed each other as “comrade.” One of them gestured a slash across the throat at me. Their love for Communism and Joseph Stalin knew no bounds–especially human sacrifice. They were much worse than the blackmailers and denouncers who emerged among the Jews and who were interested in the jobs or goods of their Polish victims–such as our neighbour Jozek Kagan, whose family we helped, but who became an NKVD informer.

Christopher Jacek Gladun was born in 1951 and grew up in Canada to where his family emigrated from England as displaced persons. Sadly, Chris died in Toronto in March 2003. He held a diploma in Journalism from the Niagara College and a BA in Polish Language & Literature from the University of Toronto. Chris also acted as interviewer and researcher for the documentary film “Rescued From Death in Siberia”.

This content is now maintained by the Kresy-Siberia Group, which Chris was a charter member of and which is taking his website and his research work forward.