Part One – Poland

Janina Sulkowska, 1934

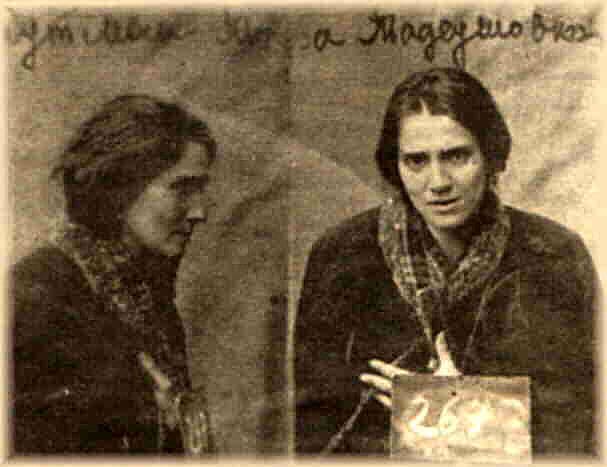

Teresa Trautman: NKVD prison photo, recovered by her mother who also retrieved her body following the execution of hundreds.

Teresa’s Agony

One day I was brought to a new and bigger interrogation room with a desk and several chairs. The guards placed me in the corner against the wall and left me alone for quite some time until an NKVD officer entered and sat down. I’d never seen him before but he was acquainted with my case from the files he carried. Suddenly the guards burst in carrying a small figure, disheveled and dressed in a filthy housecoat. It was my friend Teresa Trautman! I jumped up to embrace her but one of the guards jumped between us, and strong arms threw me against the seat. I had last seen her as a happy student in Dubno as part of our underground group–and now it was obvious that other members of our group, perhaps many, had been arrested.

“Sit down and don’t move!” the NKVD officer hissed.

Teresa was placed on the other side of the desk with her back to me, and was only be able to steal nervous glances my way. I however could study her in profile. My heart sank at her horrid appearance: pale and yellowish, her hair was encrusted with filth, while her frightened eyes darted nervously. I was puzzled by the huge cuffs that protruded from her housecoat and reached over her hands. She looked much older than her 22 years. Teresa suffered from a congenital heart condition and had always been in delicate health. I assumed by her garb that they had just taken her out of some sort of hospital–and medical care is certainly what she needed by her appearance.

The NKVD officer said nothing and deliberately busied himself with documents on his desk. Teresa was trying to communicate with me through various mimes and signs. She’d clasp her hands and raise her eyes to heaven, and then beseech me with open hands or would point to the ground while giving me sorrowful glances. Was she asking for forgiveness? Was it a warning? I really didn’t understand, nor could I answer her. But the depths of her sorrow was unmistakable and it tore my heart apart. I sent her kisses and hugs and tried somehow to reassure her that things would work out The officer was aware of our silent communications, but did nothing. He only dug deeper into the paperwork. No doubt it was his intention to let me see Teresa’s sorry state.

Satisfied with the cruel scene he’d organized, the interrogator turned to Teresa and asked her if it was true that I was the person who’d convinced her to join our subversive organization. At this, Teresa slipped to the floor and turned to me her hands trembling and folded in a prayer as if begging for mercy. The interrogator flung her back on the chair swearing terribly. I shouted that nobody had been forced to join any organization as there was no such thing! He bellowed back: “If there’s no counter-revolutionary plot then what are you all doing here!” I could not argue with his logic. “Yes, Yes–It was me,” I now lied hoping to spare Teresa anymore suffering, and added that she knew absolutely nothing and was an innocent victim of our devious plotting. The interrogator merely waved his hand to have us removed. Teresa left sobbing convulsively.

That was my last meeting with her, although I would glimpse her briefly once more, and often did communicate with her through the wall of an adjoining cell. A year later I learned from other prisoners that she had attempted suicide in her first few weeks of imprisonment in Dubno prison, around the time of our encounter. That explained the strange frilly cuffs she was wearing–they must have been bandages covering her wounded wrists that she’d slashed with broken glass. It seems an older woman had been placed in her cell and became a trusted mother-figure for Teresa who confided in her. This kind woman turned out to be a Kapus [stoolie] who reported everything to the NKVD. Quite likely that is how our names and our connections to each other fell into the hands of the NKVD who knew so many intimate details. I shuddered at the things the NKVD must have done to this poor sensitive girl whose greatest joy was helping her Mamcia and Tatus and taking care of her sisters. We all saw she was secretly in love with Zygmunt Rumel who rather had eyes for her sister Dzunia. It would not be until 1947 that I would have confirmation of her murder in Dubno prison by the NKVD from her sister Dzunia who received the details from her mother who retrieved Teresa’s body.

Brave Bronek

Bronek Rumel & Wanda Sulkowska

Shortly after my meeting with Teresa I was put through a similarly-staged encounter with Bronek Rumel who also had been arrested. It took place in the same room with the same nameless officer, but in the company of two other NKVD-types. Bronek proudly marched into the interrogation room, clicked his heels and gave me a bow, all in the best Polish tradition. He was forced to sit near the desk almost with his back to me.The interrogator slowly read aloud parts of Bronek’s statement, followed by now-familiar questions : “Who dragged who into the organization?” Bronek took blame for the conspiratorial recruitment, insisting it was he who had talked me into joining. This was not factual as I had become a member of the ZWZ before his appearance, but he insisted otherwise. The matter of the secret communiques quickly arose. As his statement was being read by the interrogator, Bronek furtively and repeatedly pointed at his breast, indicating his willingness to take the blame. As in Teresa’s case, he was not allowed to communicate directly with me. He let it be known that it was he Bronek who’d brought the leaflets and communiques from Warsaw, it was he who had distributed some of them, and it was he who had buried the rest in a can in the yard of the Trautman’s. The NKVD had taken him there under guard to recover the buried evidence, but Bronek managed to keep the location a secret–a secret he would carry to his grave.

I marvelled at this brave and selfless lad who wanted to shield not only me but everybody in the organization. But the interrogators from Moscow were disgusted by his bravery and mocked him as a foolish “Polish hero.” But they knew how to arrive at the truth.

“You can lie to the right,” one of them pointed at Bronek. “And you can lie to the left,” he indicated me. “But we’ll find the truth in the middle!”

It occurred to me that Bronek may have received orders (perhaps from his brother Zygmunt) to do his duty as a Polish soldier and sacrifice himself for the cause. In any case I realized that the affair of the leaflets and communiques could now stop with Bronek, if they believed him. There would be no more searches for them. I hung my head down and silently acquiesced to his confession. The interrogators seemed satisfied and Bronek was taken out. He clicked his heels and bowed toward me for the last time. And for me the case of the leaflets ended here; the buried ones were never found and all my hidden messages (in the soap, sofa etc) remained a mystery to the NKVD.

And that was the last time I saw Bronek in person. But I would have contact with him via the prison alphabet by which I learned that members of our group from Dubno were treated by the NKVD as a separate unit in our organization, which in fact it was. I however belonged to the Krzemieniec group. Dzunia Trautman would later supply me with other details. A circuit Soviet court arrived from Rowno and the case was tried in the cellars of the jail—but I knew nothing of what was transpiring. Bronek’s brother, Zygmunt Rumel, as leader, was sentenced to death, but in absentia. The NKVD had intercepted a postcard written by him in Ukrainian indicating he was in the Soviet zone and heading home. They laid a trap for this ‘swolocz’ [bastard] in Dubno, but only managed to capture the unfortunate Jurek Bronikowski instead. Zygmunt was warned and went into hiding. Bronek who was in jail, also received the death sentence. As did a number of students and older members, while others were handed sentences ranging from 5 to 10 years imprisonment at hard labour. Dzunia, age 17, was given 5 years. At the trail Bronek was offered a “last word” and he stated that proudly he did his duty as a Polish Officer and would do it again if necessary, even if it meant paying with his life. The Soviet judge noted it down with a few bored pen strokes. Dzunia told me all the details later in the transports. She and I were taken in a transport and survived the Dubno massacre. But Bronek did not. He died with Teresa in the executions. His body was never identified.

After Marusia was taken from my cell, I lived a solitary existence for 2 months. My home in fact was a tiny punishment-cell designed for just one person. My first day alone was May 16, 1940. It was the name-day for myself and my father Jan, in honour of Jan Nepomucen, the 14th-century Polish saint who had been imprisoned, tortured and finally murdered. Name-day celebrations are as important as birthdays in Poland and I spent the day and a good part of the night reliving all the name-days that my father and I had shared together. How many other Jans and Janinas were “celebrating” in prison? How many were dead? Undoubtedly very many as both names were as popular as John and Jane in English. It was the worst name-day I ever tried to celebrate.

A Visit to the Dentist

The next several days became miserable from a different cause. Being locked in a tiny cell all alone was bad enough, but how much worse is the agony of an accompanying toothache. A terrible throbbing pain left me in a state of sleepless moaning. Luckily I hadn’t been forced to attend many interrogations lately, but I dreaded having to go through a lengthy session with Titov or Vinokur in my present state. I reported to the prewierka [guard] that I needed to see the prison dentist immediately. Two days dragged on with no response. I finally fell into a frenzy and started to scream and hammer my fists against the cell door. At last I was taken out for a visit to the dentist in the bowels of the prison.

The dentist turned out to be a local Jewish woman who had been a successful dentist right here in Dubno, but who now didn’t hide her contempt for everything Polish, nor her new-found love of the USSR. She insisted on addressing me in Russian, even though it only served to exasperate my agony, and had the irritating habit of humming Soviet Army songs, particularly the popular Soviet Army song, Tri Tankista, or Three Tank Operaters. At particular points she would heartily slap her big ass as is if to proclaim: “Solid as a tank!”

She informed that my tooth could not be saved as there was no material for a filling. It would have to be extracted. And what’s worse there was no anaesthetic, no painkillers, not even an aspirin.

“Can you stand the pain and not faint?” she icily asked me in Polish. She looked at me as one would at a spoiled child. I smiled back and replied, “Oh please do.” I’m sure I heard her humming a Soviet song as she brandished her pliers and jiggled her huge ass. But she did pull out my bad tooth, and quite neatly. And I didn’t faint! I wouldn’t give her the pleasure. And icily I thanked her in Polish.

After Marusia was taken from my cell, I lived a solitary existence for 2 months. My home in fact was a tiny punishment-cell designed for just one person. My first day alone was May 16, 1940. It was the name-day for myself and my father Jan, in honour of Jan Nepomucen, the 14th-century Polish saint who had been imprisoned, tortured and finally murdered. Name-day celebrations are as important as birthdays in Poland and I spent the day and a good part of the night reliving all the name-days that my father and I had shared together. How many other Jans and Janinas were “celebrating” in prison? How many were dead? Undoubtedly very many as both names were as popular as John and Jane in English. It was the worst name-day I ever tried to celebrate.

Raw tobacco which I had bought in the prison commissary had long run out. The 17 rubles of mine in the prison deposit didn’t last long. My mother had forced some rubles into my cosmetic bag at the time of my arrest but I protested that money was useless in prison, and in any case I would be out in a day or two. The few articles for purchase such as leaves of tobacco, onions, garlic, pork fat, had long been unavailable to me. And one needed extra food to supplant the prison diet which consisted of a daily portion of 500 grams of bread and watery “soup”, and sometimes buckwheat or other grains. Coffee and tea of indeterminate origin were also served. Amazingly some money mysteriously did make it to me after my family had been deported. I had no idea who it was but it helped me a great deal. I later learned from Dzunia that it was her mother who had sent the money to myself and to Bronek as well as to her own two daughters. One morning during the first days of my solitary, Naczelnik Vinokur in his leather jacket and accompanied by his swit [entourage] waltzed into my cell on an inspection. He expressed surprise and even concern that I was locked up all alone. Vinokur barked an order to his staff and assured me that I’d be immediately transferred to a cell full of Polish women. I thanked him. But several days went by and I remained alone–a situation that first frightened me, but which with each passing day, I found more to my liking. Solitary confinement was used as punishment, as a method to slowly break down a person, but I revelled in my hermetic existence. In fact I considered myself lucky compared to many who were jammed into overcrowded cells with resulting lice, disease and violence.

Memory and Hope

My cell became my sanctuary, a place for reflection and work on myself–like monks who deliberately seal themselves off from the world and look inward. The interrogation sessions had largely ceased and I felt determined to survive. With a gramophone needle that I’d found, I scratched a tiny calendar on the wall behind the radiator where I kept a schedule and recorded important events. I devised a schedule of cleaning and maintenance, eating, gymnastics and cell walks which I followed faithfully. Foremost was work on myself. This featured “studying” literature and reconstituting poems I’d previously learned by heart. Luckily my parents had brought me up with a love of knowledge, and I thanked them for the passages from Polish literature I’d been encouraged to memorize. I was determined not to forget my Polish language.

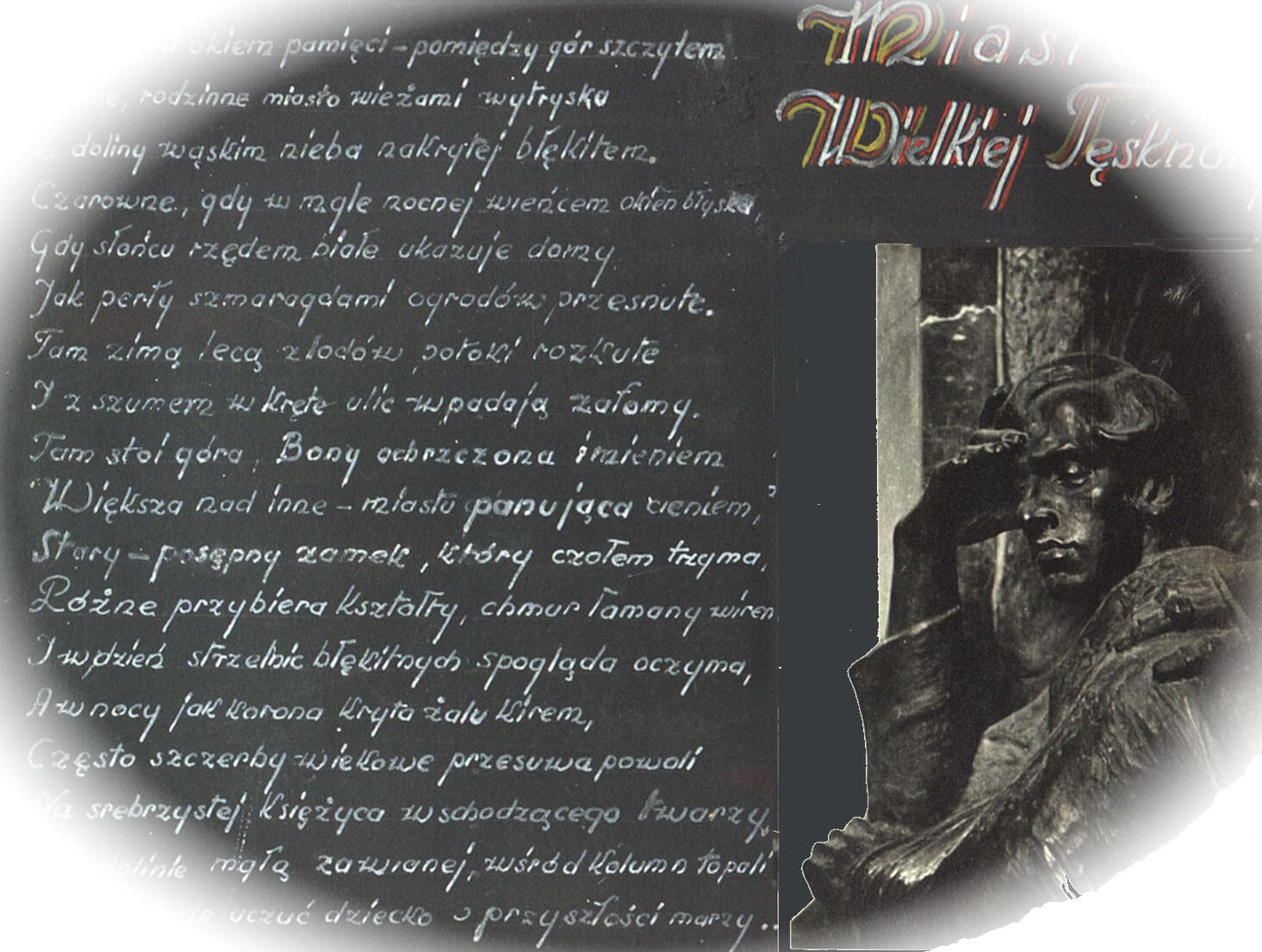

Juliusz Slowacki: photo by Czeslaw Sulkowski and calligraphy by Leon Gladun.

The Romantic poet Juliusz Slowacki, a fellow-Krzemiencian, was a major figure in my prison reflections, along with Adam Mickiewicz. Henryk Sienkiewicz, Poland’s Walter Scott, swept me through Polish history as I relived events, battles and romances from his novels. My life was rich with characters from his popular trilogy: the comic Zagloba, the dashing Pan Wolodyowski, and Longinus Podbipieta who at 7 feet in height would not be able to stand up in my cell. And the evil Teutonic Knights and the Russian Cossacks were still our enemies.

I recalled my dashed dreams for a more modern and just Poland, and relived my efforts at bridging differences among the many nationalities who were her citizens. The political climate in the 1930’s was volatile with many nationalities and ethnic groups harbouring legitimate complaints against Polish authorities and society. In the streets, political and ethnic groups battled each other, especially in university. Once at a lecture at Warsaw University given by the famous Professor Kotarbinski, I heard breaking glass and a horrid smell: an ultra-nationalist Polish student had thrown a stink bomb at the professor’s lectern! These students demanded limited quotas of enrolment for Jews and others who they felt were “overrepresented” in schools and thus deprived Poles and peasants of their rightful place in higher education. They forced Jews to stand on one side of the class or to sit in separate “quota benches.” Kotarbinski opposed these nationalists, and delivered his lectures standing up to make his point. I as well supported this position, and so sat on the side with the Jewish students. Everyone jumped up including two female students who protected the professor with their bodies, while we rushed to the aid of a Jewish friend in the cloakroom who’d been bloodied with brass knuckles. The politics of the Polish nationalists disappointed and disgusted me, as did the far left and right, including extreme Ukrainian, Byelorussian, German nationalism, Zionism et al.

I also thought about the close calls my family had, like escaping from the Russian revolution on a train commanded by Polish engineers in theatrical costumes which befuddled both sides. Or in 1920 during the siege of Warsaw, when a Bolshevik shell fell through our roof and landed unexploded in our bathtub–just feet from my sleeping baby brother! I also remembered that two of my grandfathers met their ends in Russia: one of them, a doctor, was killed by robbers while the other died digging ditches for the Bolsheviks.

Memory and Hope

Easter 1941 came and went without celebration; on my calendar I sadly noted the anniversary of my arrest a year ago. An entire year behind bars during which I would spend a few minutes in the open air under the sun on infrequent short walks in a walled compound. I could only observe the outside world on tiptoe through a scratched-out portion of my window. I was pale as a corpse. Yet Spring could not be held back by walls and gun towers. Dubno prison was surrounded on three sides by floodwater from the Ikwa River where willows were blossoming. Fragrances drifted in accompanied by seeds with delicate silky hair. The croaking of frog was my lullaby. Once a bumble bee blundered in; I asked her to fly with news to my family and helped her out the window which had been painted over from the outside but had a small spot scratched out, which I could look out on tiptoe. And what a view! People walking down the street, a wagon clattering across the bridge, boys fishing from the banks, ducks swimming–it all seemed so normal as if nothing had happened. But I had also seen groups of Polish POW’s being led to work on the roads by Russian guards with guns and snarling dogs. Their prison was at a nearby hop processing plant which had been converted into a mass detention camp.My solitary existence was periodically thrown into turmoil by searches. I’d be taken to a neighboring vacant lot where I’d also undergo a personal search, and when I returned, everything would be scattered–even the straw would be ripped from my bedding.

Christopher Jacek Gladun was born in 1951 and grew up in Canada to where his family emigrated from England as displaced persons. Sadly, Chris died in Toronto in March 2003. He held a diploma in Journalism from the Niagara College and a BA in Polish Language & Literature from the University of Toronto. Chris also acted as interviewer and researcher for the documentary film “Rescued From Death in Siberia”.

This content is now maintained by the Kresy-Siberia Group, which Chris was a charter member of and which is taking his website and his research work forward.