Part One – Poland

Janina Sulkowska, 1934

Janka (at right) with friends on an outing in the early 1930's.

Janka (left) with mother Natalia, father Jan and sister Wanda. Photo by brother Czeslaw

Krzemieniec Market

After the Attack: German bombs killed and injured dozens.

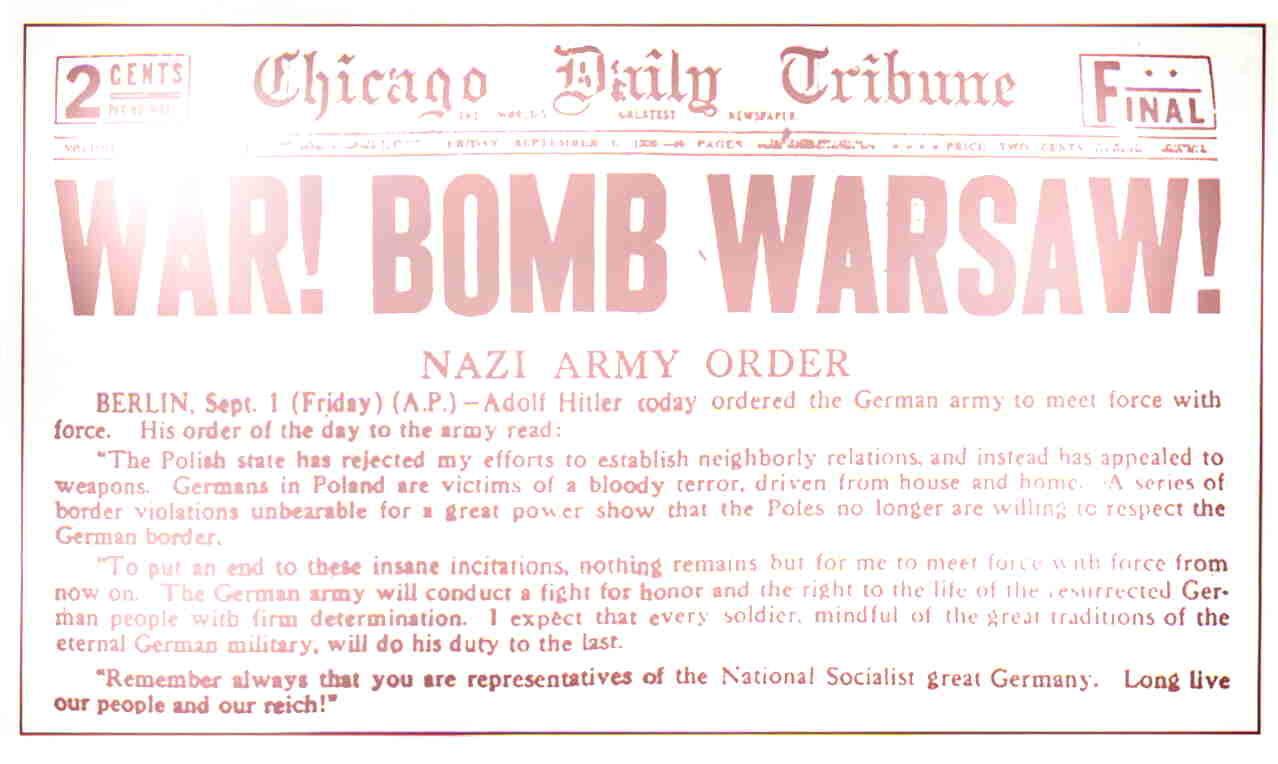

September 1939 – War!

September 1 caught me in a small village completing a sociological survey for my final year at Warsaw University. I cancelled my studies as did my younger brother Czeslaw, and we headed for home in Krzemieniec in southeastern Poland. My father Jan Sulkowski and my mother Natalia were already caught up in the events, while my sister Wanda who had just turned fourteen, was broken-hearted she couldn’t start her first year of High School.

The Nazi blitzkrieg was obliterating Polish defences, as well as targeting civilians. Into our town of 25,000, countless refugees were pouring in, seeking safety or escape to Romania in the south including thousands of Jews. Many Foreign Embassies and Legations in Warsaw had picked Krzemieniec as temporary headquarters and began arriving after September 7, as would our own Polish government. An endless stream of trains, cars, trucks, horse-drawn wagons, and finally people on foot, clogged the streets in and around the town–the dust of this traffic hung limp in the unusually hot September weather. Wagons loaded with wounded soldiers and civilians became a common, and gut-wrenching sight.

My father, as Secretary of the County, had to make arrangements to house and feed all these refugees, including providing medical care. In spite of his ill health, he was on the go 24-hours a day. Our own house very quickly became a home to many poor souls who had nowhere to go. My father’s responsibilities included accommodating the various ambassadors and foreign dignitaries as well as our own Polish ministers, and even entire government departments. The Papal Nuncio was placed in the prefect’s house of Krzemieniec Lyceum, and I helped to house staff from several embassies in the school dormitories while other foreign staff were put up in the old monastary or in private homes. The wife of my godfather Jan Podosowski, an old friend of my father’s, arrived at out doorstep with her daughter and a servant girl. He folllowed shortly on foot and under fire. (They would all be deported by the Soviets to Siberia, as would we all, though that was still months away).

In the winding streets of Krzemieniec one could now could come face to face with Polish leaders and politicians. Returning from an errand I ran into a famous Cabinet Minister seated in front of our garden gate with his head hung down and sighing. I entered by another way. The President of Poland, Ignacy Mosciski and Marshal Rydz-Smigly were saluted by our Boy Scouts who stayed and fought, and showed more courage than their fleeing leaders.

There were a number of famous American journalists who called Krzemieniec a temporary home including Alex Small of the Chicage Tribune, Mr. Shapiro of The New York Times and Mr Neville from Time magazine. Shortly they would escape, while we remained.

My little sister Wanda, too young to understand the unfolding tragedy, found this traffic fascinating. She would race through the streets with her school chums searching for the latest embassy arrival. Her prized possession was an atlas that showed all the flags of the world. Each embassy vehicle carried a national flag on the front, and the trick was to identify the country. With friends gathered about her, Wanda would consult her atlas, and with great pomp would announce: Brazil, Greece, Turkey, and so on. One car that was easily identified was the huge yellow Cadillac of the United States, which in Krzemieniec was painted over except for a USA on the roof.

I myself took part in a bizzare encounter with an embassy car, and some very undiplomatic diplomats. While on an errand for my father, I beheld a car racing down Szeroka [Broad] Street. Careening from side to side, it finally clanged to a stop like some exhausted beast in front of me. I couldn’t help but notice the flag draped over the roof–was it really the Japanese sun? Where was my sister and her atlas! The dust settled and the doors flew open. Two Oriental men in wrinkled suits tumbled out arguing. They were very drunk. Dumbfounded I watched as they staggerred behind some trees where they noisily relieved themselves. They then jumped back into the car and drove off with their flag flapping loudly as if to say: “Germans, please don’t bomb us–we’re you’re allies!”

A few days later I would help one of these Japanese “dignitaries” light his cigarette in our local bomb shelter–his hands trembling at the thought of another encounter with Nazi planes. It was also in this shelter that the Swedish Ambassador would trip and break his leg in a dash to safety.

Strange Cargo

One morning my father dragged himself from his frantic duties at the County Building with an amazing story. In hushed tones he told me that a heavily-laden truck arrived in the dead of night, and that its contents–bricks wrapped in paper–were unloaded and stacked in a pyramid in the hall. My father asked one of the men on the truck, what it was they were unloading. He smiled and told my father to help himself to one of the mysterious bricks.

“UFF!” my father demonstrated to me how he struggled with its surprising weight.

Unwrapping the brick he discovered the source of such heaviness: a solid gold brick! In fact he was holding one of the bars of Poland’s gold reserves (estimated at $80,000,000) which were secertly being shipped beyond the clutches of the Gestapo–and which eventually would make their way to Canada and England. By morning the truck and mysterious bricks were gone, and nobody was quite sure about the entire affair of Poland’s gold reserves passing through Krzemieniec.

German Air Raid

Thursday was market day in Krzemieniec, and since before dawn of September 12, local farmers and sellers had been streaming into town bringing their produce. The market square quickly filled up as Jewish shopkeepers opened their stalls and newspaper boys shouted the latest war news. Business was unusually brisk as many shortages were developing.

It was 10:30 in the morning and I was helping my mother and a servant girl with bags and baskets as they set out for the market to feed ourselves and the many refugees in our house. Suddenly the high-pitch scream of diving planes caused everyone to freeze. There had been a number of false air raid sirens previously–but this time there was no warning of what was a very real attack. Countless explosions shook our house followed by the rat-tat-tat of strafing machine-guns. We could only stare at each other in horror. Later reports would confirm that several German Stukas had screamed out of a blue sky and flew so low that people could actually see the pilots’ face. The planes followed the valley into town and dropped several bombs along the main street–and then returned to strafe the market. The carnage was terrible. My sister on an errand, had grabbed a playing child and headed for a cellar while my brother was caught on the street going to register our radio, but he hid behind some concrete poles.

Over my mother’s objections, I immediately ran to the market and beheld a horrific scene: wagons overturned, vegetables intermingled with body parts, people screaming and running around. A number of buildings were aflame or in ruins. Searching the skies in rage, I beheld the macabre sight of a Jewish woman’s sheytl [traditional wig of a married woman] hanging from electrical wires and dripping brains. Beside me an old peasant woman stood moaning in a puddle of blood in a state of shock, while a teenaged girl thrashed about in pain as her family wailed. This was an attack by the Nazis calculated to create terror among the inhabitants and to send a warning to the embassies and to the world.

As I walked about trying to help the victims, a car arrived bearing a Swedish film crew, who with professional detachment filmed the destruction and death–a 30-second newsreel of a Nazi attack on a defenceless town to be shown along with the latest comedies!

Christopher Jacek Gladun was born in 1951 and grew up in Canada to where his family emigrated from England as displaced persons. Sadly, Chris died in Toronto in March 2003. He held a diploma in Journalism from the Niagara College and a BA in Polish Language & Literature from the University of Toronto. Chris also acted as interviewer and researcher for the documentary film “Rescued From Death in Siberia”.

This content is now maintained by the Kresy-Siberia Group, which Chris was a charter member of and which is taking his website and his research work forward.