Part One – Poland

Janina Sulkowska, 1934

The Sulkowski Home in Krzemieniec.

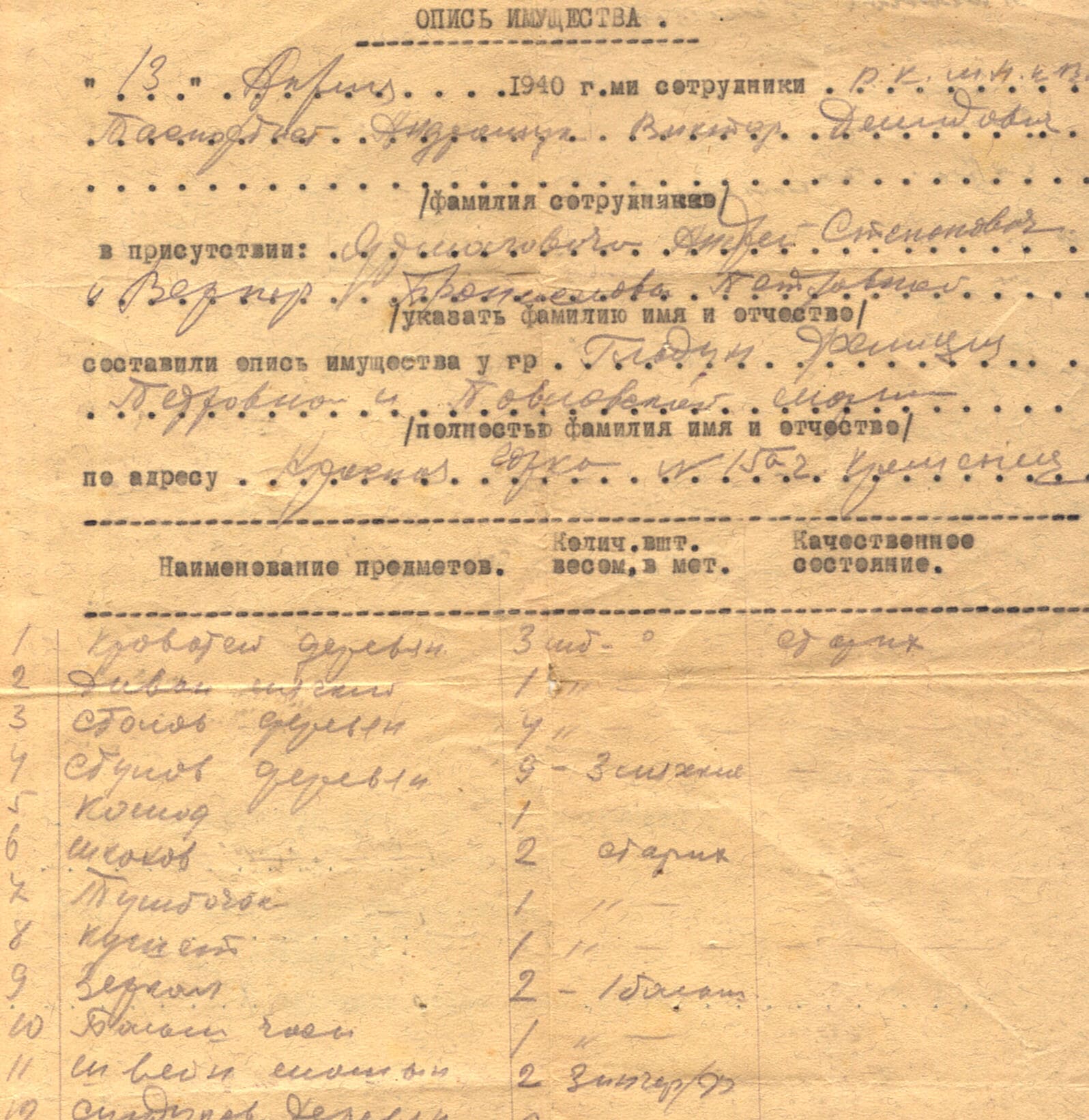

NKVD "Receipt" for property stolen or sold at low prices to the Soviets and their collaborators.

My Family is Taken Away

Three weeks after my arrest, my mother and younger brother Czeslaw and sister Wanda, were taken away in the night by the NKVD and their collaborators–and shipped by cattle car to Siberia. Some fifteen members of my family would find themselves in prisons, POW camps, at forced labour or in concentration camps, from Germany to the Arctic to Asiatic Siberia…and years of exile followed. Those who remained in Poland faced five more years of the Holocaust and Soviet terror. A number of school chums had fallen in the defense of Poland in September, and the war would claim more. Józio Szmaltysch and Leon Gladun were two of many acquaintances held as POWs by the Soviets–and transports were commencing to a place called Katyn. Only eight students from my graduating class of twenty-four, survived the war.

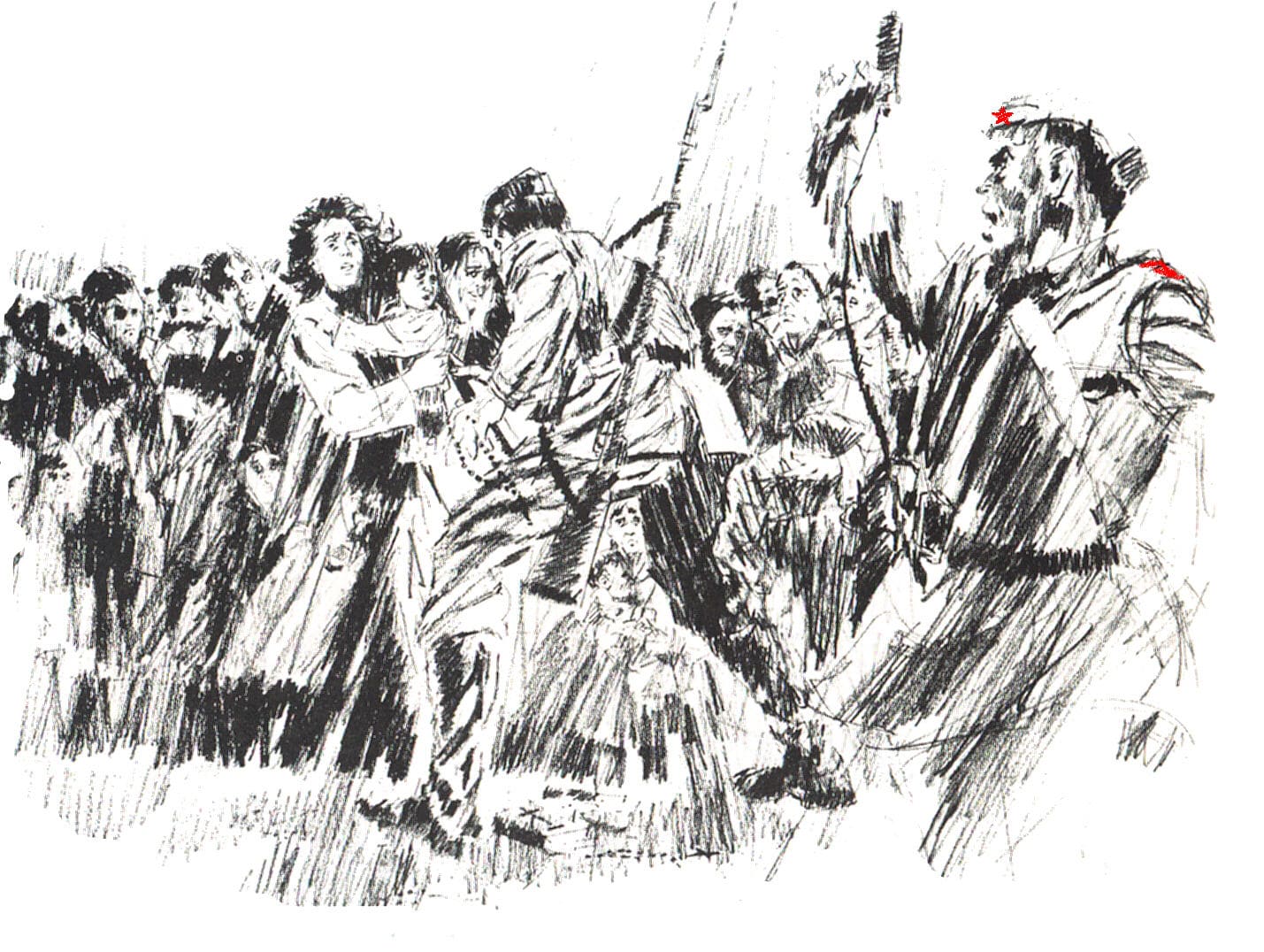

In April a second wave of deportations swept up members of families of people previously arrested or who’d escaped, and tradesmen and farmers. The majority of the estimated 320,000 victims were women and children many of whom would die in transport. On the night of April 13, a Ukrainian and a Jew, both neighbours, burst through the Sulkowski door with a Soviet soldier in tow. My family was given just thirty minutes to pack and were in a state of shock–where does one start? Similar scenes were taking place all over town as soldiers and militia dragged families into requisitioned wagons with the aid of dogs and bayonets. Screams and tears filled the night.

My 22-year-old brother Czeslaw, immediately began packing items into suitcases and showed my mother and sister how to make bundles of clothing. The Soviet soldier followed him everywhere and refused to let him take an axe as it could be used as a weapon. Meanwhile the Ukrainian and the Jew looked for plunder. In horror Wanda realized that she would not be allowed to take her beloved cat Zbik; with tears streaming down her face she beseeched her mother who was beside herself and could only tell her that it would be a lot colder where they were going.

Suddenly it was announced that the keys to the house and property had to be turned over to someone for “safekeeping.” My mother surmised that the only ones who were safe from the Soviets were the poor Jews–and her choice fell on Abraham Baraczin, a shoemaker who lived nearby. The soldier sent for him. Tearfully she handed over the key to our possessions and asked Baraczin to distribute certain items to whoever of our friends might still remain in Krzemieniec after this

terrible night. My little sister clutched the hands of the shoemaker and begged him to take care of Zbik, to which he promised. My mother was even issued official and itemized “receipts.”

Baraczin did manage to send them some money to Siberia, but in the end both our fortunes and Zbik would “run away” as most of our property was stolen or sold at ridiculously low prices at an NKVD auction. My mother would try to contact Jewish friends to look into matters of property and the trial of my father, but as far as they were concerned, the Sulkowski family and their things had been liquidated–family photos would be thrown into the flames by those who wanted the frames!

Felicja Gladun and her mother were among those taken in Krzemieniec. Felicja’s crime was accepting Polish citizenship and for having a son who was scheduled to die at Katyn (Leon Gladun survived–and would eventually become my husband!).

It was also a terrible night for my family elsewhere. Granny Urbanska along with mentally sick Stefa and and two nephews, Adas and Krzys, ages eleven and three, were put on the transports. At a rail station in Siemiatycze they joined Konstancja Warczuk, the sister of my uncle, and her sick 90-year-old mother Barbara Wolk who had been loaded into the wagon on the door the NKVD had kicked in. They would be transported some 80 kilometers from my mother but would have difficulty meeting as Poles were forbidden to leave the borders of their confinement. Three “Grannies” would perish there and the survivors would return to Poland only in 1946. My godfather disappeared without a trace in Siberia.

A week later I was to experience an unusual and “shocking” method of torture which had been concocted by my tormentors. I became a guinea pig in their advancement of the art of arriving at the “truth.” This was their “electric chair.” I was taken at night for a regular session. Titov and Vinokur were unusually attentive and asked questions slowly. I returned vague answers. They slowly asked me one more time, and I muttered back. They then looked at each other–and suddenly I was thrown out of the chair by some great force. I found my self on the floor with my right leg twitching and in pain. What had happened? They picked me up and put me back in the seat. I was asked the same question again, which I didn’t know how to answer–and once more I was hurled into the air. I shook like a rag doll. The shock was repeated a third time and I started to choke…but the disembodied voice of Vinokur announced that he was satisfied. I was dragged back to me cell. My body felt peculiar but not in particular pain; it took my mind somewhat longer to recover. I was never again subjected to this–but I always looked at my seat for signs of tampering. I could only shake my head at the thought of Titov and Vinokur rigging up the chair with wires and experimenting on me to determine the proper voltage and power to torture–but hopefully not to kill me.

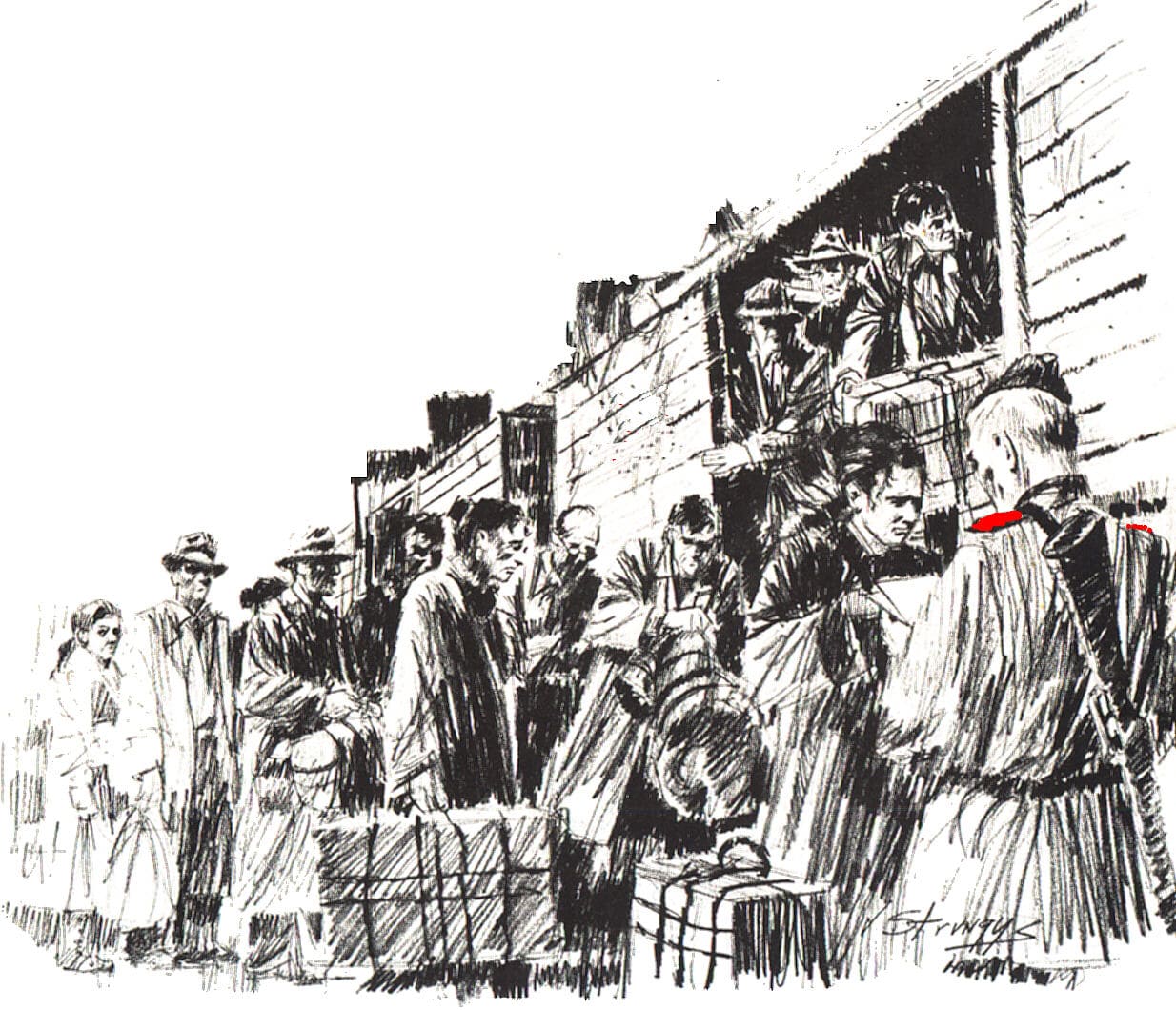

My family was loaded with their makeshift bundles into wagons and driven to the train station where other wagons were disgorging their human cargo to the shouts of “Bystrej!” [Faster!] and “Dawaj po vagon!” [Into the wagon!] while soldiers with bayonets and the local Jewish and Ukrainian militia brutally kept back frantic relatives. A soldier smashed one woman in the face when she tried to hand food to a relative. People were crammed 60 or more to a cattle car with no facilities or water, and no heat (two feet of snow fell). That night, and through the next day and night, wagons and trucks brought in more people from the area. During this time my brother managed to escape, and ran 8 kilometers and back, with a sack of bread and other food for the wagon. He was caught by a guard who simply couldn’t believe that someone wanted to get back into the wagon!

Finally on Sunday night the train set off for a destination that filled every Pole with dread: Siberia. As it steamed out, it was to the sound of hundreds of voices singing Polish hymns and patriotic songs. The train would pick up more prisoners along the way and would be over a hundred wagons long when it left Polish territory. The trip took two weeks under such brutal conditions that the seasoned train commandant (who expressed sadness over the fate of Polish children) committed suicide under a locomotive when the transport finally arrived. Bodies, mostly of babies or the elderly, were discarded through holes. At the end my mother and siblings were thrown off in a field on the steppes and told: “Work–or die!”

Russian Roulette and an “Electric Chair”

Following my family’s arrest, my interrogations became more vicious–the anger in Titov and Vinokur now flowed to the surface. They screamed in my face and promised me a death sentence. They paraded tortured friends in front of me whom they would later murder. They kept my in solitary confinement and in a frozen cell. And they tortured me.

One particular session is burned into my memory. It seemed like another dreary night. I was dismissing Titov’s predictable questions with my usual shrugs and denials–it was a routine that we both played well. Then Vinokur emerged from the background, twisting my chair close to his face.

“So you don’t think I could just kill you like a dog!” he growled.

I sensed this was something more than the usual threats. He narrowed his eyes and a muscle twitched in his cheek. He undid his holster and took out a black revolver. Suddenly I realized he was brushing my cheek, and then my temple with the barrel. I could distinctly feel the click of the trigger and rolling of tumblers. “My God!”–he was playing Russian Roulette against my head.

“Believe, Believe, you Polish bastard!” Vinokur screamed and pulled the trigger. The sound of the hammer exploded in my head–but no bullet came forth. And then he pulled it a second, and then a third time. I shuddered each time. Titov’s eyebrows wriggled with excitement as I struggled in my chair and came close to fainting, Then the gun was put away.

Later in my cell, I decided that it was just a game they were playing, and that there were no bullets–but I still would feel sick every time I thought of it.

A week later I was to experience an unusual and “shocking” method of torture which had been concocted by my tormentors. I became a guinea pig in their advancement of the art of arriving at the “truth.” This was their “electric chair.” I was taken at night for a regular session. Titov and Vinokur were unusually attentive and asked questions slowly. I returned vague answers. They slowly asked me one more time, and I muttered back. They then looked at each other–and suddenly I was thrown out of the chair by some great force. I found my self on the floor with my right leg twitching and in pain. What had happened? They picked me up and put me back in the seat. I was asked the same question again, which I didn’t know how to answer–and once more I was hurled into the air. I shook like a rag doll. The shock was repeated a third time and I started to choke…but the disembodied voice of Vinokur announced that he was satisfied. I was dragged back to me cell. My body felt peculiar but not in particular pain; it took my mind somewhat longer to recover. I was never again subjected to this–but I always looked at my seat for signs of tampering. I could only shake my head at the thought of Titov and Vinokur rigging up the chair with wires and experimenting on me to determine the proper voltage and power to torture–but hopefully not to kill me.

It was also a chair, that in a slower and less dramatic way, inflicted even more excruciating pain. Barely 5 foot 2 inches, my legs dangled like a child’s when seated in the interrogation chair. The sessions always lasted through the night during which I was not allowed to eat or go to the washroom. The torture lay in the cumulative effect of having my limbs in suspension with lack of muscular activity and circulation, and the effect was very painful. After several months of repeated sessions my legs and feet were swollen and in pain. And it was most excruciating when I would first stand up from the chair. I never imagined that such pain could result from merely having your limbs dangle.

However I realized that my interrogations at the hands of the NKVD were relatively mild compared to what many were subjected to. Leon Kowal was repeatedly beaten as was Pius Zaleski. Others had needles jammed under their fingernails, hands crushed, testicles burned. Women were routinely raped or kept in cells of freezing water. Women with babies were not given proper food and had difficulty feeding infants, who then would be taken from them. Executions were common.

Christopher Jacek Gladun was born in 1951 and grew up in Canada to where his family emigrated from England as displaced persons. Sadly, Chris died in Toronto in March 2003. He held a diploma in Journalism from the Niagara College and a BA in Polish Language & Literature from the University of Toronto. Chris also acted as interviewer and researcher for the documentary film “Rescued From Death in Siberia”.

This content is now maintained by the Kresy-Siberia Group, which Chris was a charter member of and which is taking his website and his research work forward.