Part One – Poland

Janina Sulkowska, 1934

Basia Poniatowska and Krystyna Krahelska, Krzemieniec, 1933. Krystyna was the model for the Warsaw Siren statue which symbolized Warsaw and the struggle against Nazism. Both Basia and Krystyna perished fighting in the Warsaw Uprising.

By Grzegorz Polak, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2211936

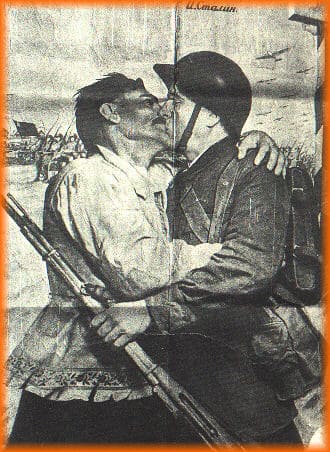

"Our Army is the army of liberators of the workers." But mass executions and deportations were Soviet policy aimed at Poles in Krzemieniec and occupied Poland.

Our Conspiracy Begins

Surviving friends (some had perished, many were imprisoned or POWs, while others were caught behind German lines) began to return to a Krzemieniec under Soviet rule. Among the first was Bronek Rumel, followed by his brother Zygmunt with Leon Kowal–the pair had escaped the Soviets and were hiding in Dubno. Mobilized from university as reserve Polish officers, they had been taken prisoner by the Red Army, as were some 240,000 Polish soldiers. The NKVD was killing officers so they discarded their uniforms and passed as ordinary conscripts. Other local officer cadets like Leon Gladun and Józio Szmalstych were still missing. Finally Pius Zaleski returned from Warsaw where he’d fought against the Germans to the bitter end. Our university days were just a bittersweet memory–but the flame of resistance was not snuffed out.

A number of us met in nearby Dubno at the house of Dzunia and Teresa Trautman, ages 17 and 22. We memorized passwords, sang patriotic songs and conjured ghosts with a Ouija board. desperately We wanted to fight the Soviets and the Nazis–but who could lead us? We approached Jakub Hoffman, a local leader, who was smuggling out the wives of Polish officers and was respected by all–the NKVD had sniffed around in the Ukrainian and Jewish communities looking for denouncements, but only got positive testaments. His choice and ours was Henryk Józewski, Voivode [Reeve] of Wolyn. Bronek and Pius set off in January on a mission to contact him on the German side where we assumed he was hiding. But they were double-crossed in a terrible snowstorm, and hobbled back with severe frostbite. Many escaping people perished that winter, from the weather and from border guards. I then met with Hoffman who revealed to me that “Henryk Józewski is still in Poland!” He had remained in Poland organizing anti-Nazi partisans in Wolyn and Polesie. Thus our mission to find him was recalled and we returned to our home bases.

We set out to contact dispersed friends and make recruits. Zygmunt Rumel went in search of our beloved friend “Basia” Poniatowska, daughter of Juliusz Poniatowski, Minister of Agriculture, as well to find friendly recruits among Ukrainians. She had made the noble and fateful decision to stay on her family estate and fight in Poland. Zygmunt came back with news that she had been last reported fleeing hostile German colonists–and that her buggy had been found overturned and her horse killed. (Years later I’d learn that Basia did become a member of the underground and fought in the Warsaw Uprising, and was killed by the Nazis in 1944.)

A second brave compatriot of ours who stayed in Poland was Krstyna Krahelska, noted for her singing voice and repertoire of Polish/Ukrainian folk songs with which she often personally regaled us or performed on the radio. Krystyna was chosen by the sculptor to serve as a model for the Warsaw Syrena (mermaid) statue erected just before the war, and which would come to

symbolize the city and the struggle against Nazism. The statue miraculously survived, but Krystyna did not –she perished in the Warsaw Uprising. Today her memory and sacrifice is honoured in Poland.

The Soviets Take Over

Kovalenko, the Russian Commandant of Krzemieniec immediately arrested our senior government and leading citizens in the first of a series of incarcerations, torture and deportations which would also claim my family and myself. Two local Jewish Communists were quickly appointed to top positions: Avraham Raz, became chief of police while Moche Mayer was mayor (later replaced by a Ukrainian, Kustriva). From the Jewish refugees that had been welcomed to our town, others stepped forward to participate in the new Soviet administration. Terror likewise faced my relatives caught under the Germans, and in many cases the Soviets and Nazis worked together to eradicate Polish opposition.

My father was removed as an official of the Polish government and now worked in the office of a peat mine where my brother toiled at digging. Much of our home had been requisitioned and my mother was forced to sell or barter many of our possessions. Food and fuel shortages were the order of the day as the Soviets bought up or confiscated whatever they could–even an apple was now a delicacy.

For Poles and for those among the Ukrainian and Jewish communities who opposed the Soviet occupation, life was hell. The NKVD made good use of collaborators especially the local Communist party which was almost exclusively Jewish and was headed by Comrade Rabinowicz. In any case there were no Poles in the inner party. From headquarters in the requistioned Treasury Office refurbished lavishly with plundered goods, the NKVD would decide the fate of their victims over vodka and fine food, aided by those who for reasons ranging from politics to settling a grudge, eagerly denounced suspect citizens. Anyone handed over to the NKVD ceased to be a free person, and in time the interrogation organs would find the appropriate crime and sentence, usually 8 years of forced labour in the camps. Even walking down the streets of Krzemieniec was an ordeal as the NKVD and their Jewish or Ukrainian militia would arrest a person on any pretext–even for being well-dressed.

Krzemieniec Lyceum Humiliated

What particularly distressed me was the humiliation of my beloved Krzemieniec Lyceum which was revered as a great Polish institution that welcomed students of all background, rich or poor, Polish, Ukrainian and Jewish.The Soviets methodically transformed it into a repressive Communist model, threatening and firing the staff and students. Directors and teachers were appointed from local Communists whose main qualification was loyalty to their Soviet overlords; later staff was brought in from the USSR. I can never forgive those Krzemiencian Poles, Ukrainians and Jews who played a great part in the destruction of the school from which some of them had graduated. Many however mourned the loss even as large numbers of new students, Jewish and Ukrainian, poured in to eradicate the despised Polish presence enhanced with free room and board. We became so alarmed that we contemplated somehow closing the school if it fell below 200 Polish students. With my own arrest, I would only witness the early stages of destruction.

The duties of School Director fell to two local Jews appointed by the Communist party. One of them was an accountant named Segal with Cwik, the Jewish publisher of Lyceum texts, while the other, Pinchas Pinczuk, was a Communist who had been imprisoned by the Poles. My sister brought back horror stories of “education” under the cruel Pinczuk and his wife, who used Jewish children to betray their classmates for wearing religious symbols or being patriotic, often with deadly consequences for the whole family. My classmate from the Lyceum and Warsaw University, Marek Tkaczuk, a fierce Ukrainian Communist, was another instant director who betrayed his friends and the institution that had given him so much. School inspector was taken over by a Jewish female doctor who demanded students donate money to the “International Organization of Revolutionary Help”–with dire consequences for those who didn’t. A number of Jewish “assistants,” spies and stoolpigeons spread the new order which would see Polish enrollment decline, including my sister who quit in disgust–but both Polish and Jewish students despised them and their master Pinczuk. But several Polish students and professors were arrested, interrogated and sentenced to death for belonging to a “counter-revolutionary Polish organization.” Ironically their Soviet death sentence would be thwarted by the Nazi invasion in the summer of 1941–only to be then carried out by the Nazis. The Soviets emptied the school libraries and dumped them into a pile for destruction while the priceless Lyceum library of 40,000 books was put in the hands of a young Jew who functioned as head censor and book-burner with the task of eliminating texts not conforming to Communist “ideals.” Some students did sneak in and save a book or two from the pile.

I Take a Solemn Pledge

In Rowno I stayed with my aunt Irma Wolk, wife of Stanislaw Wolk, President of Rowno, who was trapped on the German side. Secretly I made my way to the home of Antoni Hermaszewski where I delivered my oath into the hands of Colonel Majewski himself. I was to become his liaison and a courier of communications across Wolyn. Majewski supplied me with passwords and the specifics of members in Luck, Dubno, Krzemieniec and elsewhere. I wrote the information down in code on tiny leaflets–and in a copy of the Constitution of the USSR. Majewski’s codename was “Szmigiel,” but we called him “grandpa” because of his beard, though he was only in his mid-forties.

As a Secret Courier

Dressed a poor student, I ferried secret messages between a number of cities and contacts. The trains ran irregularly and the stations were dirty with Soviet guards everywhere. I had a hollowed-out bar of soap where I hid the leaflets made of very thin but durable material, while another hiding place was a child’s rubber toy! My aunt also supplied me with 100 comuniques of war-news from the Polish Government-in-Exile in France, which the Colonel advised me to disperse to our members. I concealed the flyers in my aunt’s sewing machine which was sent by rail to Brest and later retrieved. I made contact with two of the sappers from Warsaw, one of them Jurek Bronikowski who had papers under the name of Popatow, and who later would find refuge in my home.

In February the first massive wave of Soviet arrests swept up hundreds of thousands of government officials and others including Jakub Hoffmann and his family. I quickly helped my aunt Irma escape across the Bug River with her two small daughters–but her two sons and mother were forced to remain behind as the ice broke-up (and they would be deported to Siberia). As well my mother’s half-sister, Lusia Madalinska, and her husband’s mother were deported to Archangel in the Siberian Arctic.

One of our direct actions was to smuggle a typewriter from Krzemieniec Lyceum; devices of communication were being confiscated by the NKVD. The exits were now guarded by the local militia, and we despaired of getting it out–until my own mother stepped in. She coolly smuggled it out in pieces hidden in her basket under rolls of cotton, right under the noses of the armed and bullying Jews! The machine was then hidden with friendly Ukrainians.

Our Conspiracy Unwinds

Janka (centre) with Leon Gladun (left) on a picnic in the mountains of Krzemieniec

March, 1940, found me at the Trautmans in Dubno. Zygmunt had left for Warsaw but Bronek his brother was present, and had buried some of my leaflets in a barrel outside in a secret location. And then Dzunia brought horrible news from school: students and professors had been arrested including our members, and our cache of weapons had been uncovered by the NKVD. It was suspected that someone connected with the organization had betrayed us. I decided to return home for Easter at once.

My train was scheduled for 3 a.m. I lay dressed as Dzunia drowsed and Bronek read “The Silver Dream of Salome” by Słowacki. It was strange and dream-like. Setting out for the station, we observed a huge building from the Ikwa bridge. This was the modern jail, modelled on the American Sing-Sing, that the Polish government had been building–but which now was an NKVD fortress crammed with Polish prisoners. We were amazed at how prisoners could sleep in such a glare. We moved out of range of the recent Soviet searchlights and gun towers, little realizing we would find ourselves here very soon–and that for some it would be their place of execution.

Arriving in Krzemieniec I observed my beloved hills, but felt little joy.

Most of our house had been requisitioned, my father was sick and had

lost his job, my sister had left school and my mother was pawning things–

but they were alive. Jurek Bronikowski (the sapper from Warsaw) had

arrived the night before and was busy helping my mother prepare Easter

baked goods. He quickly informed me that many members had just been

arrested by the NKVD, and that he had fled to my house in Krzemieniec as a hideout. But evil forces were already closing in.

Christopher Jacek Gladun was born in 1951 and grew up in Canada to where his family emigrated from England as displaced persons. Sadly, Chris died in Toronto in March 2003. He held a diploma in Journalism from the Niagara College and a BA in Polish Language & Literature from the University of Toronto. Chris also acted as interviewer and researcher for the documentary film “Rescued From Death in Siberia”.

This content is now maintained by the Kresy-Siberia Group, which Chris was a charter member of and which is taking his website and his research work forward.