Part One – Poland

Janina Sulkowska, 1934

The Streets of Krzemieniec

My First Days Behind Bars

It was late evening as I was bundled into the car between guards and driven to our former police building which was now NKVD headquarters. First I was taken to the jail next door and locked in an empty cell for an hour before being escorted to the office of Commandant Kovalenko, a handsome Armenian.

“Do you have a fiancé in Dubno or Rowno?” he asked, shuffling through the papers and documents taken from my home. I replied “No” not suspecting the question. (Later I found out my father claimed I had a fiancé there, in order

to mask my underground missions). I asked Kowalenko why I was under arrest. He told me not to worry–I’d find out soon enough.

I was taken to the adjoining jail composed of five cells housing men and women undergoing nightly interrogations which were very often brutal. I curled up alone amid the smell of human urine and feces, and could hear female voices through a vent, but I was afraid to make contact. This was the NKVD jail, while the main prison in town, designed for 150 people, was now jammed with 500 prisoners whose diet consisted of cow ears, tails and intestines. Hundreds would be tortured and executed here.

In the middle of the night I heard a roll-call of prisoners with familiar names: Galkiewicz, Basinski, Jagodzinski–but one of them sent a jolt through me. It belonged to my father. I could hear them coughing in the hall when suddenly the peephole in my door, the so-called “Judas,” quickly opened and three fingers squeezed in and waved at me. I recognized my father’s long slender fingers! And then he was gone as the prisoners were taken to the main prison. That was the last sight I had of my father for over two years. Next morning a horse-drawn sleigh with two NKVD guards took me away. I assumed they were taking me to the main prison, but when we turned onto the main road, I realized we were bound for Dubno. It took us the whole day to cover the 25 miles.

“Nachalnik” Vinokur

That evening on the outskirts of Dubno, a car with a driver and guard were waiting to take me to NKVD headquarters. I believed I could convince the Soviets to release me, but I also knew that the Soviets had mowed down countless people with machine guns on these very streets. At NKVD headquarters, I was taken to Major Vinokur, the Nachalnik [commandant] for Dubno region, who was dressed in a black leather jacket. His office was crammed with looted items: mirrors, an old-fashioned sofa, tapestries, a glass-case with jams and conserves. Major Vinokur was seated behind a large desk and asked me to sit down as if I were an old friend who’d just dropped in for some tea from his samovar. Vinokur spoke in Ukrainian (he was a Jew from Kiev) and I answered in Polish. He impressed me with his knowledge of Polish literature, but it disconcerted me that he knew dates and places connected with my education and travel. Through our “conversation” a number of NKVD officers would silently enter the office, sit down, and closely observe me. Finally Vinokur introduced one of them as my “personal” interrogator who, along with two others, had been sent from Moscow to handle my case! I felt like a mouse being toyed with by cats, and Vinokur who purred so beautifully, had the sharpest claws.

NKVD Officer

I was peppered with questions in Russian, but I just shrugged my shoulders. A dim-witted Jewish girl was called in as translator but I was able to befuddle her, and she was sent away by Vinokur who decided to demonstrate to the boys from Moscow the finer points of an interrogation. I continued to play the part of an innocent victim, indignant at being dragged into such a misunderstanding, and amused at being surrounded by so many important men saying such terrible things! A quiet moment ensued, and Vinokur gently wheeled his chair around, and with his back to me, fiddled with the radio. Pleasant music filled the room which relaxed the tension. My gaze was wandering over a Polish tapestry hung upside-down on the wall when abruptly Vinokur turned back, and in perfect Polish asked: “And how is Pius Zaleski’s health?”

“Oh, better now, thank you,” I replied–and immediately recoiled in horror. How did Vinokur know that Pius had suffered frostbite in trying to cross the border on our secret mission!

“So you do know Pius!” Major Vinokur growled, and fixed me with a gaze that was black and utterly soulless. A numbness came over me as I realized that Pius and probably many others, were in Soviet custody. How easily I had fallen into Vinokur’s trap. I felt like a child caught with her hand in the cookie jar and could only hang my head in confusion and fight back tears.

“Take this polskaia kurva [Polish whore] out!” Vinokur waved his hand as the men from Moscow nodded their heads in awe.

Dubno Jail

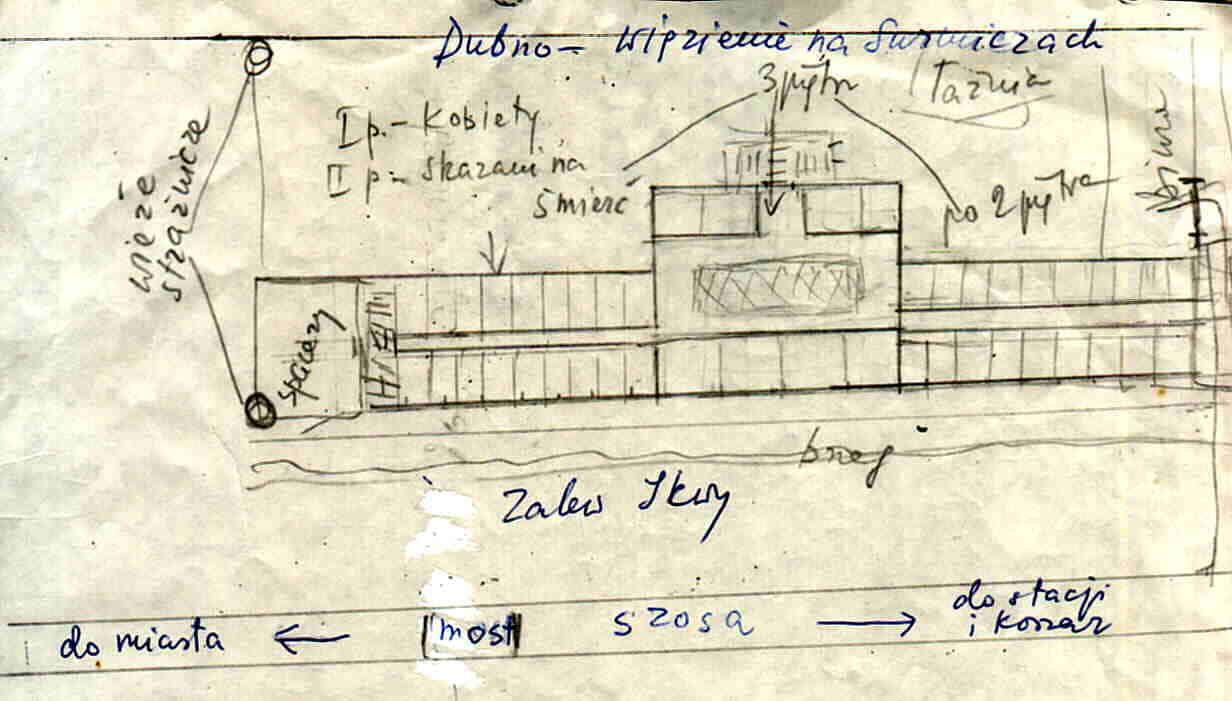

The guards drove me across Dubno to the very same jail which we had observed on our trek to the railway station. Was that really just a few days ago? The middle section of the prison was three stories high with two expansive wings of two stories on either side, and guard-towers on the corners. I could not yet conceive of what lay in store for me inside but it was a horrid feeling when the gate clanged shut behind me. I was taken into the processing section and pushed into a windowless room where a female guard ordered me to strip. She checked my pockets and possessions, then began on my body. My garter, belt, shoelaces and even my compact kit were confiscated. My garnet necklace was also taken–but it would miraculously survive endless revisions and adventures, and is still in my possession. And then I experienced what I thought were my last moments. Marched toward the prison office, I was suddenly thrown face-first into a recess and pressed flat by the guard: I awaited a quick shot in the back of the head! But I was pulled back and we continued. I soon realized that this painful detour (my nose was bleeding) was a precaution to prevent prisoners from coming face to face.

Dubno Jail: the Soviets filled the jail to several times capacity. Thousands of Polish prisoners would be tortured and executed here. Janka just escaped the mass killing by the NKVD in June of 1941, when she was transferred. Many of her friends were not so lucky. (Drawing by Janina Sulkowska, 1990).

The Question of the Secret Messages

I was led upstairs to a room which was hot and bare except for two chairs. Sergei Titov, my “personal” interrogator, entered and sat down. He looked absurd thanks to his recent eyebrow highlighting and slicked hair–outdated movie star looks were the rage among Soviet officers. Titov began his Soviet “song and dance” routine: “How could I be duped by that bastard Sikorski? If I confessed now the Soviet Union would forgive me and I could live in happiness and equality.” I just shrugged and smiled back. His interrogation was concerned with our anti-Soviet communications and leaflets, focusing on a copy of an original leaflet made by Dzunia which was found in my home. In fact the NKVD never produced a single leaflet or any other piece of evidence. I’d later discover that Bronek was forced at gunpoint to help the NKVD in a search for the leaflets I had given him and which he buried–but without success. Still it was obvious that someone had talked–or been forced to talk.

I had not been given water or food for two days now. I lost track of time. The questioning went on into the night, or was it already morning? Titov sent for a replacement, an uneducated soldier who made sure I didn’t sleep. He kept droning on about what a wonderful paradise the Soviet Union was and how factories in the USSR manufactured oranges. He insisted that I write down my “confession” on the paper that Titov had provided. At one point I asked the soldier if I could borrow his pocket mirror–and I was transfixed by the eyes of a hunted beast in which there was almost no iris! I agreed to start writing my “confession” hoping to catch a few winks at the desk. Like a drunk on a barstool, I scribbled my name and other innocuous details.

Finally I was sent back in the care a female Ukrainian guard (many positions were filled by local Ukrainians and Jews, while higher functionaries were from the USSR, and under NKVD supervision). I was pushed into my solitary cell and collapsed upon the straw mattress–but shouting and banging of keys jolted me. Each attempt to nod off brought the same response from a guard who scrutinized me through the Judas. Whenever I slumped down, the door was flung open and screams hurled at me. A bright bulb filled my eyes with buzzing pain.

Inner Strength

I started to pace: four steps to the door, and four back. This prison wing was made up tiny “solitary” cells, just big enough to lie down on an elegant parquette floor. A small radiator stood near the door and the tiny window, painted from the outside, could be partially flipped open from the top. This prison was being completed by the Poles as a modern institution for criminals modelled on Sing-Sing, but now it was run by the Soviets for Polish political prisoners awaiting deportation to hard labour. The irony was not lost on the Russians and the staff who joked that it had been constructed by Polish men so that their wives would have somewhere to languish! And we would answer: “And a wonderful job they did too!” Under the Soviets it held 1,500 prisoners, including 250 women and 50 children, ages 12-15, both boys and girls–but at one point 3,000 would be crammed inside. Among them were pregnant women whose babies would be given to Soviet families while they would be sent to Siberia. Women being interrogated were routinely raped. In the massacres of June 24 to 25, 1941, some 550 prisoners (other estimates run as high as 1,500) perished here–my friends among them.

Suddenly I felt a sensation of being watched: a guard’s eye was staring at me through the Judas! I began to pace while the eye kept watching. I thought I’d go mad and attack that disembodied eye! But I calmed myself with inner strength. I decided not to give in to the NKVD. Slowly I fell into a trance and realized that I was blessed with an opportunity to experience something amazing, a chance to “earn” my soul, which I must not squander. I had never experienced such a state of grace and strength, and without it I might not have survived what awaited me.

That evening I was taken to my second interrogation session that lasted till morning. Titov cursed me and tore up my “confession”–but I serenely smiled back at my interrogator’s contorted face. He was amazed and asked me if I’d been allowed to sleep. The question of the leaflets was still his concern. In spite of my exhaustion, I tried to lead his investigation down a blind alley with the invention of a refugee named Mrs Dolska–it was she who had left the incriminating leaflet in my home.

Christopher Jacek Gladun was born in 1951 and grew up in Canada to where his family emigrated from England as displaced persons. Sadly, Chris died in Toronto in March 2003. He held a diploma in Journalism from the Niagara College and a BA in Polish Language & Literature from the University of Toronto. Chris also acted as interviewer and researcher for the documentary film “Rescued From Death in Siberia”.

This content is now maintained by the Kresy-Siberia Group, which Chris was a charter member of and which is taking his website and his research work forward.