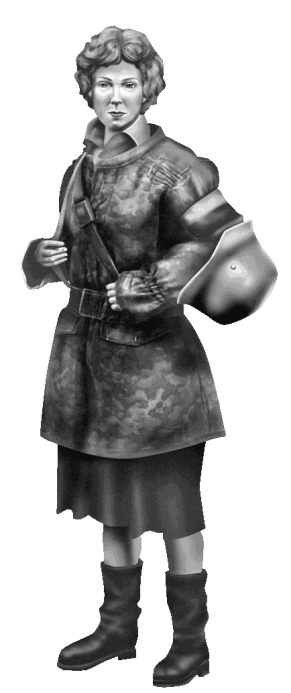

Barbara

Member of the Home Army (Wilenska AK) in Wilno area, North Eastern Borderlands.

Listen to her narrative

Repatriation

It was ironic that in 1945, when Polish civilians from earlier deportations were coming back, we from the Home Army were sent in the opposite direction, to the Komi Republic, for extended exile.

At the end of WW2, Poland’s borders shifted. The historical Kresy was handed over to the USSR. The new Polish-Soviet border ran along the River Bug, leaving Polish towns and cities such as Lwow, Vilnius, Tarnapol, Pinsk, Brzesc, Baranowicze, Grodno and Rowne on the Soviet side.

The Polish communists, who had agreed to the concession of our territory, transferred over one and a half million people from the east back to their “homeland”. This included Polish people still living in Kresy being transferred to western Poland and also Polish people originally from Kresy who were still exiled in the USSR. They would not be returning “home” but to a new, western Poland.

During 1944, when the war still raged, repatriation was resisted from Polish people living in the Kresy. Of course, we considered that to leave our homeland undefended was tantamount to treason.

In 1945 when it was clear that the former eastern borderlands had been handed to Moscow, population transfers increased. It was a huge wrench for us to leave our homeland. My neighbour wrote: “Each Pole felt torn by his conscience: Poles truly love Poland but they also love their villages where they were born, where they had their forests and ponds, where their fathers’, grandfathers’, and great grandfathers’ farms were, and where ashes rested in ancestral graves”.

Incentives were even offered – those who had the deeds to their property were eligible for a farm in the west. But the process was often chaotic. A report in September 1945 noted : “The Plenipotentiary was notified that a train departed on a given day and that he was supposed to get 1,000 registered persons to the station. The repatriates assembled for that purpose on open-air platforms. As a rule, they waited for the train for 10 to 15 days, unable to cook food, unable to find shelter from rain or wind, and exposed to robbery at night. They could not go back to their homes they had sold their flats and furniture”.

In central and western Poland Wloclaw, Szczecin and Olsztyn attempted to replace the lost cities of Lwow, Wilno, Stanislawow and Grodno.

Between 1944 and 1948 one and a quarter million people were repatriated from the Soviet republics of Ukraine, Byelorussia and Lithuania to Poland. Meanwhile, hundreds of thousands of Poles who had been deported in 1939-41 still languished in the vast Soviet interior.

In the spring of 1945 a government Repatriation office was established. On 6 July, the Soviet Government agreed to grant to “Poles and Polish Jews who were citizens living in the USSR the right to renounce their Soviet citizenship in favour of Polish and the choice of returning to Poland if they so wished”.

The majority of Poles were transferred back to Poland in 1946 with priority given to military families and also farmers and highly-skilled workers. Most came from Kresy so the Poland they were returning to would not be their “homeland”.

The firsthand account of a ZPP official in Kazakhstan is testimony to the desperation of Poles registering for repatriation: “On the first day at four o’clock in the morning a crowd of some four and a half thousand people gathered in front of the main NKVD building. Even though the documents concerning change of citizenship had to be dealt with in alphabetical order, everybody came on this first day. Even the Zalewskis, Zakolickis and Zyzwaks. There was no force on earth that could chase away this weeping, impoverished, feverish vortex. They stood until late in the evening, only to begin their vigil at dawn the next day. Thus in continued for thirty hot, work-filled days of the “option”, until the last Zyzwak had added his signature…”

Delegates toured Soviet orphanages and kolkozes to collect Polish children. Many had been adopted by Kazakh or Russian families. They were covered in fleas, half-wild and worked as shepherds. Most had forgotten their parents and their Polish.

The refugees were in a poor physical and psychological state. The authorities ensured that they were fed and clothed for the journey. This was clearly because the Soviets did not want the western world to see the half-starved state of the refugees emerging from incarceration in the USSR.

It was a mammoth operation. Transports passed through border check-posts, such as those at Brzesc, Medyka and Jagodzin, where documents were checked. Within Poland staging-posts had been set so that the repatriates could receive hot food.

The total number of Poles repatriated from the interior of the USSR, that is beyond the “Riga Line”, between 1945 and 1948, was just over 250,000 people.

While their exile was finishing, mine was only just beginning.

Facts

21.07.1944 – Proclamation of the Polish Committee of National Liberation in Lublin, a provisional government under the protection of USSR in opposition to the Government of the Republic of Poland in exile, in London…

Facts

21.07.1944 – Proclamation of the Polish Committee of National Liberation in Lublin, a provisional government under the protection of USSR in opposition to the Government of the Republic of Poland in exile, in London.

09.09.1944 – Agreements with the Ukrainian SSR and Byelorussian SSR on population transfer. On the basis of the agreements Polish citizens were forced to resettle on the territories of post war Poland.

22.11.1944 – Agreement on population transfer with the Lithuanian SSR.

11.02.1945 – Yalta Conference. USSR, Great Britain and USA affirmed the Curzon Line as the new eastern border between Poland and the Soviet Union. Poland loses the Borderlands to the Soviets.

06.07.1945 – Agreement between the Soviet Union and Poland on the repatriation from the USSR territory of all those Poles and Jews who were able to prove their Polish citizenship obtained before WWII.

1945-1946 – Repatriation from the Soviet Union to Poland of the 1940 – 1941 exiles and inhabitants of the Easter Borderlands, the former territory of the Second Polish Republic.

1956-1957 – Another repatriation agreement between Poland and the USSR. More than than 200,000 Polish citizens come back to Poland from the USSR interior and the former territory of the Eastern Borderlands during the years 1955 – 1956. Thousands of those unable to prove their Polish citizenship were left behind.

1989 r. – Fall of communism in Poland.

26.12.1991 r. – Dissolution of the USSR.

09.11.2000 – The Repatriation Act so that people without Polish citizenship but of Polish origin have the right to come back to Poland. It allows the repatriation of Poles who had remained in the East and in particular in the Asian part of the former USSR due to deportations, exile and other ethnically-motivated forms of persecution, to re-settle in Poland.